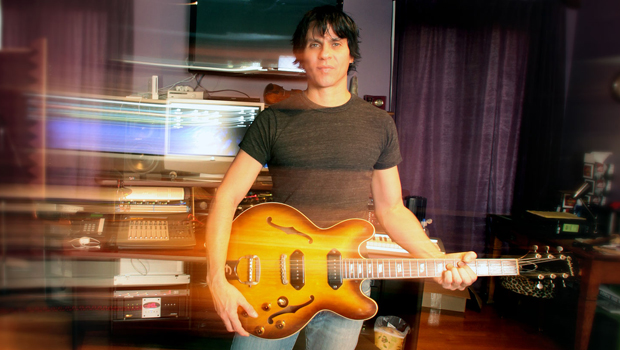

Interview: Producer/Musician Will Evankovich on Importance of Theory and How Guitarists Can Maximize Studio Time

Will Evankovich’s resume is a 25-year musical encyclopedia encompassing his skills as a songwriter, producer, arranger, singer, performer and multi-instrumentalist.

Evankovich plays guitar, bass, mandolin and percussion and has enjoyed success with several recording and touring bands that he launched, including Mason Lane, The Stereo Flyers and most recently, American Drag.

From 2007 to 2009, he toured with Jack Blades and Tommy Shaw, rounding out the sound of their Shaw/Blades project. He was handpicked by Blades, who had seen American Drag perform and wanted Evankovich to join them on acoustic, 12-string, harmonica and background vocals.

This was Evankovich’s introduction to Shaw, and it launched the friendship and working relationship that led to his production of Shaw’s highly acclaimed bluegrass album, The Great Divide, which debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard Bluegrass Chart. He also produced Shaw’s tracks for Styx’ Regeneration Volumes I and II package.

Evankovich recently discussed how studying music theory was integral in his understanding of performance and recording, and offered some insight for guitarists about studio preparation and tracking.

When did music become a part of your life?

There were a couple of pivotal points when I was really young, 4 or 5 years old. I’d listen to the M.A.S.H. theme on television, grab the guitar and start figuring it out before I really knew how to play at all, so it seemed I had natural proclivities to picking out the notes in a song right away and quite easily. I knew at that point that this is what I was supposed to do. I loved music and it was a no-brainer for me, so I started playing guitar when I was 6, and I started taking instruction around 7 or 8.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What types of music interested you?

My father was really into music and he was in some doo-wop-style groups in the early ’60s. He would play Cat Stevens, Stevie Wonder, Chicago and all these great songs from the early ’70s. He was a big part of my first musical influences. When my parents went to work, they took me to a nanny who would play Beethoven and Mozart when we would go to sleep in the afternoon. Everybody else was knocked out in the first five minutes, but I loved it so much that I would sit there and listen for the duration of the nap period. I think it was a combination of these people influencing me with whatever they were listening to at the time. My older brother listened to hard rock stuff, and he introduced me to Styx and Led Zeppelin and those sorts of things.

When did you discover production and arrangements?

I had always been fascinated with the structure of the songs, and I’d always see words like “Jimmy Page produced the Led Zeppelin records.” A lot of people don’t get what that means. I equate it, in layman’s terms, to you’re the director of the film. You kind of oversee all processes of the songs from the very beginning to post-production. Orchestration and arrangement is something that I started learning more and more about as I got deeper into music and started paying attention, listening not just to the guitar parts, but also the bass and drums and the arrangements of all the instruments. I listened further and got into the art and construction of the songs. The Beatles, of course, were probably the most influential in my early teens.

I began to understand what production was about, listening to all the Beatles' records and going through a phase that drove my mother crazy. That’s when I started to recognize the value of production, with George Martin and string arrangements — this “fifth Beatle” sure did an awful lot! When I was young, I could never figure out why he wasn’t a part of the band. Never mind the fact that he was in his 40s or 50s! Jack Blades, whom I work with a lot, of course everyone’s a giant Beatles fan, but his studio is just littered with Beatles paraphernalia. He got to work with Ringo Starr at one point, so he lived out one of his dreams. I think we all secretly wish that one day we’ll be able to meet a Beatle, and it’s hard to believe that two of them are gone. George was my favorite, and he’s probably the most unsung hero. “Something,” in my opinion, is one of the best Beatles songs; it’s just such a beautiful song. We could talk about the Beatles for hours.

You also studied theory. How did that help hone your skills?

I did a few years of private instruction, from the age of 7 until my teens, and I was in the jazz band in high school, which was my theory journey. I really wanted to go to Berkeley, but my parents didn’t have a lot of money. I grew up in Santa Rosa, and the reputation of the Santa Rosa Junior College music program was really good, so I took all my theory classes there for two or three years. I went through the whole program, and it was amazing and every bit as good as any other institution.

I don’t think kids should shirk their junior college music program, because if you apply yourself, you can learn anything you want there. It really changed my perspective about reading and writing music. One of the things I like to do in the studio is work with players who read and write music. Once I’ve hashed out all the arrangements, I’ll chart the music, the guys come in, and within two or three takes they’ve done the song. There isn’t a lot of guesswork. We talk out some nuances and things, and it speeds things up when the language is out there like that, so I've found it to be the most valuable thing I’ve ever done as a musician.

When did you open your studio?

I’ve been building it over the last five years and putting together the gear that I needed. I typically do drums at other places. A drum room is a very specific thing, and the spaces in my studio are not conducive to recording drums. There are other rooms that are tuned and they’re the right size. Alan Hertz is an amazing drummer, in addition to the fact that he’s great at recording, and he has a great room that I like to use a lot. He’s also a terrific mixing engineer and he mixed The Great Divide. I do not mix. I love to be there for the entire process, because after putting all your hard work into arrangements and writing and everything, it’s pretty much the final course, so I’m right there with the mixing engineer, driving them nuts, but I do not mix. It’s a fine art that I have great appreciation for, and that’s one of Alan’s talents, in addition to playing drums and recording them. I focus my studio on recording guitars, acoustic instruments and vocals.

What are some of the common mistakes guitarists make in the studio, and how can they overcome them?

The biggest one, I think, is a lot of guitar players naturally play on top. That’s kind of the nature of the beast. I think it’s what gives the guitarist feel and excitement, and that’s never to be discounted, but one of the most common follies of guitar players in the studio is that I don’t believe they practice to a click very often. A lot of times they’re rushing against the click, almost to the point that you have to wave them back. You’re excited, and the parts you’re playing are exciting and very interesting, and I don’t ever want to lose that, but conversely, I want the feel to be really nice.

So sometimes, when they get the click on, they’re finally going and they say things like, “Why don’t you nudge me back?” After a period of time I start to think, Well, instead of relying on the engineer to fix you when you’re done, you should just spend some time with the parts that you're going to play. I can’t emphasize enough the value of practicing to a metronome. I will take a guitar player who’s got amazing time over a player who’s got amazing lead chops for days, because probably the most valuable thing in the studio is someone who can (a) be diverse in what they play, but (b) also execute it in a groovy fashion.

The thing I see most typically in the studio that goes wrong with guitar players is their lack of a good-time feel or too rushed of a time feel. That’s one. Two, when you’re in the microscope of the studio, the intonation of your instrument becomes grossly apparent. Live, I think a lot of guitar players don’t realize how their intonation might not be spot on, and so when they get in the studio they realize they’ve got some serious intonation issues with their guitars. Their stuff is very pitchy, and then they’re sitting there with a screwdriver, trying to adjust the intonation at the last minute and sucking up hours in the studio.

So I guess the three pieces of advice are (a) play to a metronome, (b) learn your parts as well as you can before you get into the studio, and (c) have your instrument set up and your intonation locked in. If you’ve got that, then the vibe and all that other stuff will just naturally fall in and you’ll have a good time and sound good.

— Alison Richter

Alison Richter interviews artists, producers, engineers and other music industry professionals for print and online publications. Read more of her interviews right here.

Photo: Tommy Shaw

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.

“Around Vulgar, he would get frustrated with me because I couldn’t keep up with what he was doing, guitar-wise – Dime was so far beyond me musically”: Pantera producer Terry Date on how he captured Dimebag Darrell’s lightning in a bottle in the studio

“He ran home and came back with a grocery sack full of old, rusty pedals he had lying around his mom’s house”: Terry Date recalls Dimebag Darrell’s unconventional approach to tone in the studio