Interview: Kirk Hammett Discusses Metallica's 'Death Magnetic'

This interview is from the Guitar World archives (2008). Be sure to check out our Death Magneticinterview with James Hetfield, which appeared in the same issue of GW.

Kirk Hammett is wired and tired.

It’s evening in Los Angeles, and in approximately one hour, Metallica will hit the stage of the Wiltern Theater to raise money for the Silverlake Conservatory of Music, a nonprofit music school for low-income students. While Hammett is psyched to be playing for this great cause, there is no denying that, at the moment, he’s draggin’ ass.

“I tried to sleep in this morning, but I couldn’t because I’m on baby time,” he explains. “I have a one-and-a-half-year-old, and my wife’s giving birth to another baby in about six weeks. I’ve been getting up at 6:30 in the morning, so this is already getting late for me.

“I’ll have to reset my rock and roll clock if I’m going to have any chance of making it through the next tour,” he adds, laughing.

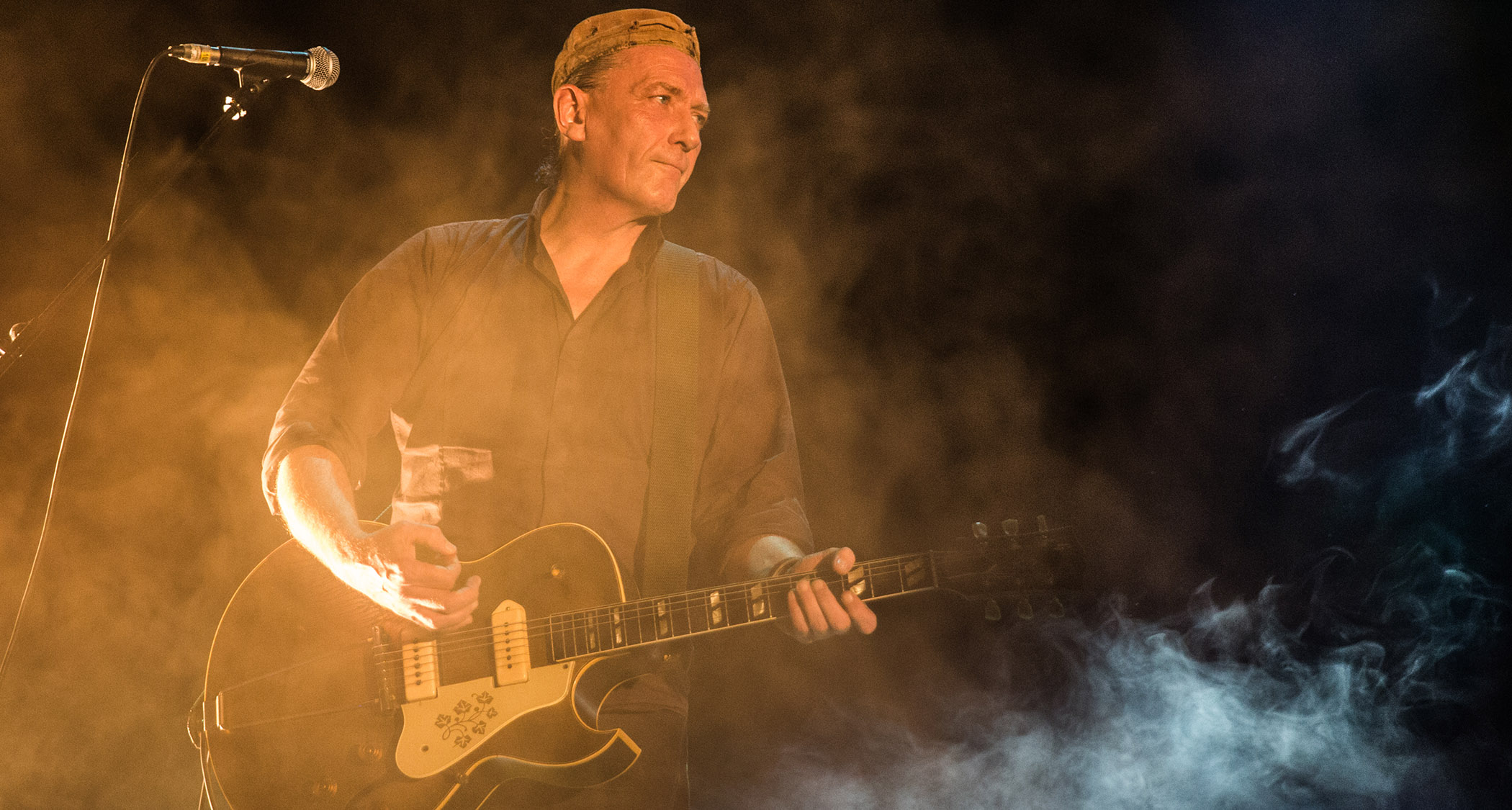

Hitting the reset button has become a theme for Hammett and his band over the past year. After spending much of the decade redefining their sound, Metallica have gone full circle and returned to the crunching, thrash-metal style that established them as the world’s greatest hard rock band in the Eighties. While it’s tempting to attribute this dramatic about-face to their superstar producer Rick Rubin, Kirk explains that the band did much of the heavy lifting on their new album, Death Magnetic, themselves.

“Rick was important because he planted the creative seeds, but he left the lion’s share of the execution to us,” Hammett explains. “It was a great relationship, because he gave us guidance but left our core intact. For example, if there were anything he thought was substandard, or just wrong for us, he would just tell us to write something else; he wouldn’t try to tell us how. There was a lot of mutual respect.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When asked why, after 20-plus years in the business, Metallica didn’t just produce the record themselves, Hammett laughs and shakes his head. “We need an outsider, or else a lot of creative decisions would become stalemates and we’d never get anything done,” he says, referring to band’s notoriously turbulent relationship. “We need a tiebreaker. Maybe if there were a fifth person in the band it could work, but at this point we’re not about to get a keyboard player.”

One thing the band could apparently agree on was to give Hammett plenty of room to rip. Considering that he was all but forbidden to play solos on the group’s previous studio effort, St. Anger, it’s both a shock and a relief to hear him cut loose on Death Magnetic. As frontman James Hetfield explains in the accompanying interview, putting one of the greatest soloists in rock history on a short leash probably wasn’t a good idea. To Metallica’s credit, they’ve more than made up for the error by allowing Hammett to play fast, loud and long throughout Death Magnetic. In fact, one could argue that Kirk practically owns the album.

The mellow surfer-dude yin to James’s tough-guy yang, Hammett takes this vindication in stride. In the following interview, he talks with modest pride about his new lease on Death and how goddamn good it feels to be “face melters” once again.

GUITAR WORLD: How would you describe Death Magnetic?

I would say it sits somewhere in between …And Justice for All and the “Black Album.” It has an aggressive, technical side, like Justice, but there’s also a lot of melody, like the “Black Album.” We wrote the album with every intention of it being just a kick in the face, and I think we pulled it off. We’ve been working on it for long enough—close the three years. At one point we had 24 songs, and we had to tear it down to 14, and it has even fewer now, but I think it’s everything that we wanted to hear.

Was there a lot of discussion about how the band wanted the album to sound, or did the sound unfold naturally?

I remember we had a meeting with Rick Rubin back in 2005, and we had already written some music, and we played it for him. We talked about what he wanted to hear from Metallica and what his ideal Metallica album would be like. He also planted the seed in our heads that it would be okay for us to reference our past. So during the entire creative process we allowed ourselves just to be ourselves.

It was actually very exciting to be able to look back at the formulas that worked for us in the past and gather new inspiration from them. We gave ourselves permission to take the best aspects of our past and combine them with the best aspects of what we are now to create something totally different.

You should be allowed to plagiarize yourself. Everybody else has stolen from Metallica.

Yeah. [laughs] Well, we spent a long time trying to distance ourselves from our early music to prove to ourselves that we’re more than just that. And that’s pretty much what the Nineties were. We were just exploring our own potential creatively and figuring out what we were capable of and what we could get away with. We’ve passed that. And now we just wanna go out there and be the world’s heaviest band again.

Are you conscious of how much your sound has permeated metal?

Yeah, it’s interesting. I’ll put on satellite radio and hear something and think, Hey, we did that in 1987! Who is this band? It’s flattering, and it’s fun for us. I don’t think we see that as a negative thing at all. I only say that because you can imagine how an artist might think they’re being ripped off. I see it as a tribute.

It might be beyond that. They probably grew up listening to Metallica, and to them, that’s just the way metal should be played.

Yeah, our sound is part of the lexicon. The metal lexicon!

How would you say you’ve changed as a guitarist from, say, …And Justice for All?

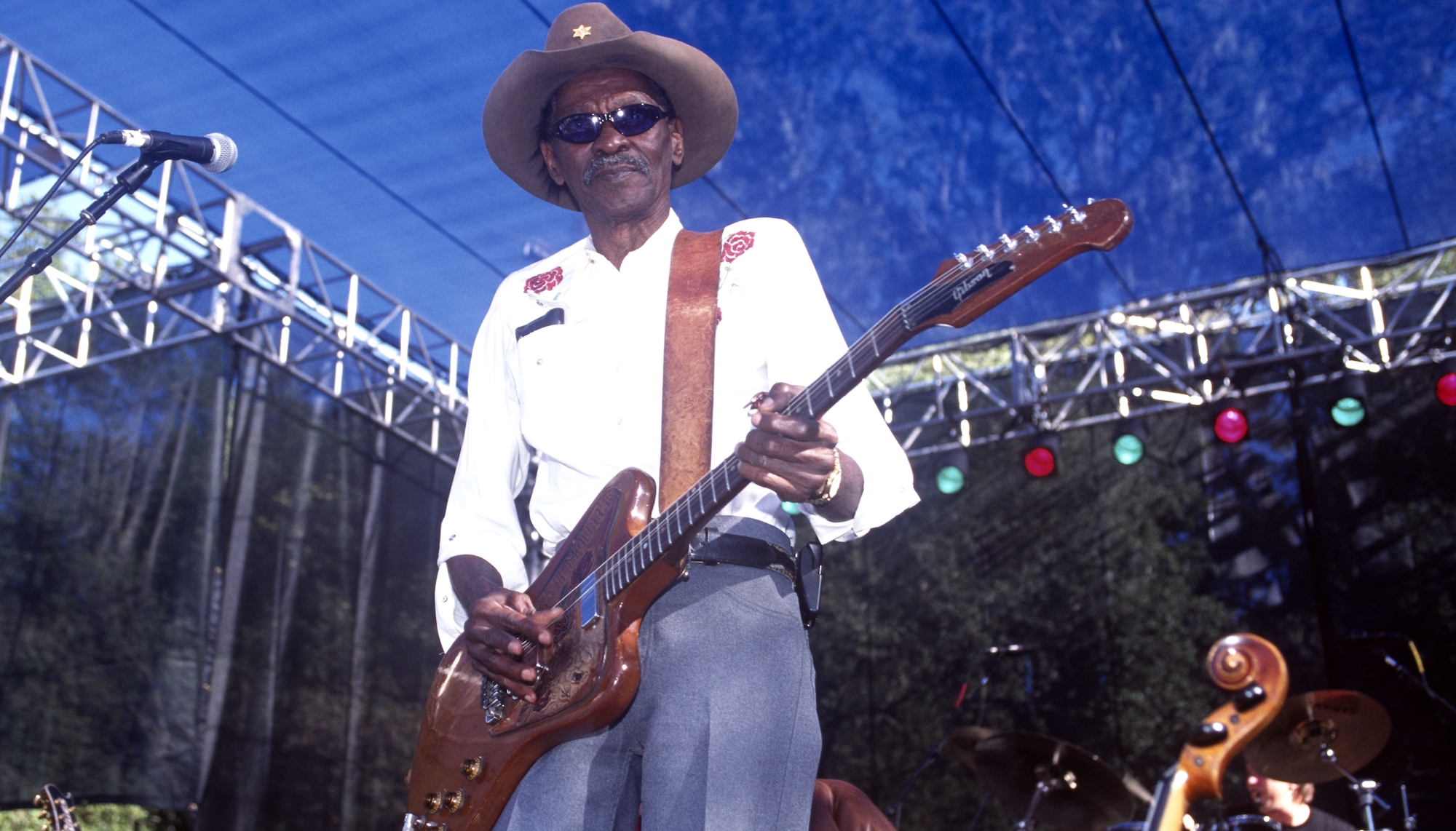

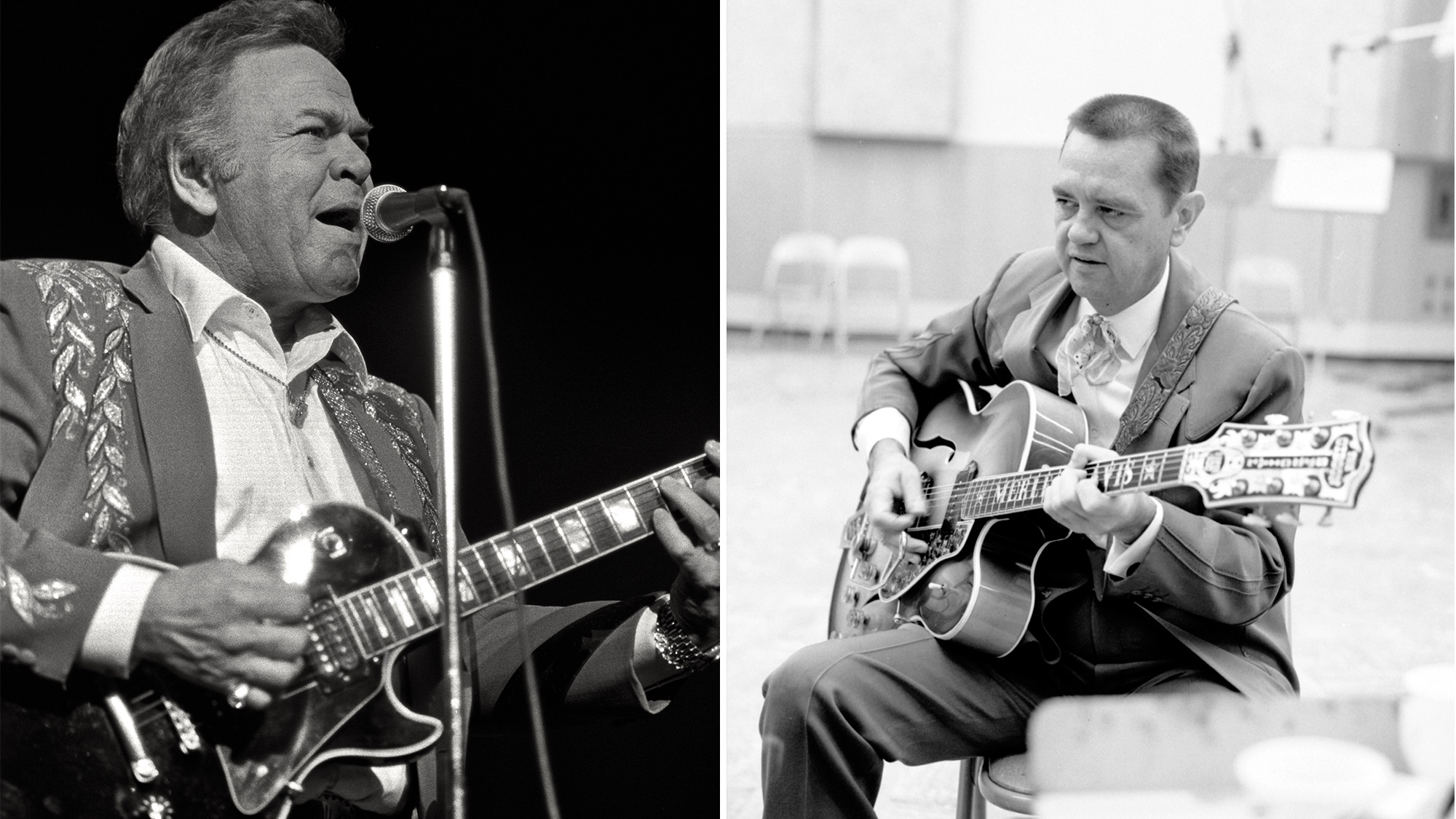

Well, I went through a whole blues period in the Nineties and that had some influence on Load and ReLoad. Then I started listening to a lot of jazz—stuff like Kenny Burrell, Tal Farlow, Grant Green and Wes Montgomery—guys who were just monsters on the guitar. It was a great education, because I discovered where all of my rock heroes got a lot of their licks. Jeff Beck, Clapton, Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Jimmy Page all took ideas from those players and turned them into the vocabulary of their generation.

I drew it all in, and it changed my style totally. However, a couple years ago I started feeling like I was going too deep. I’m back to being primarily a metal guitarist, but some of the blues and jazz ideas have changed me in important ways. My improvisation skills have really improved—I flow a lot better; I’m putting a lot more faith in my abilities to be spontaneous—whereas in the past I would compose my solos. Ninety percent of the time my solos on past albums were composed, where now, I would say, it’s maybe 40 percent.

I’ve been pushing myself to the limit in the studio—right to the very edge of the abyss. And I took my playing into areas I’ve never been before. I’m currently relearning the songs for our upcoming tour, and I’m scratching my head going, “What did I do there?” I can’t remember what I did, and I can’t figure it out. I might need the transcribers at Guitar World to help me! [laughs]

One of your thrash metal contemporaries, Alex Skolnick of Testament, has recorded a couple of straight-up jazz albums as the Alex Skolnick Trio. Have you heard them?

Love them. I love his work. What Alex is doing by putting heavy metal songs in a jazz context is completely refreshing. His take on [the Kiss classic] “Detroit Rock City” [from 2002’s Goodbye to Romance: Standards for a New Generation] blew me away; that song has never sounded better to me. And when you think about, the old jazz standards were the pop music of their time. So Alex has updated the notion of what a standard is, and it’s opened up all the current music to interpretation. The idea of playing Kiss or the Scorpions in the style of Dave Brubeck is great and quite radical. There are tons of people at Julliard who are playing [Thelonious Monk’s jazz standard] “Straight No Chaser” for probably the 50 millionth time, so it’s about time somebody tried something new.

I was playing your ESP Mummy guitar, and I noticed that your action is quite high. You definitely have some fight in your guitar.

The fight brings out more emotion. If a guitar is too easy for me to play, it makes me too laid back. I like to battle with my guitar. My pick attack is hard, and when the action’s too low and you have a hard attack, things just start buzzing all over the place.

When I was talking to James, I thought it was interesting that he returned not only to his classic sound but also to the instrument and amplifier that he used on a lot of Metallica’s Eighties recordings. Your sound, however, is quite different from those albums—it’s bigger and has less bite. Many of the solos have a really bold, singing quality.

I’ve added more midrange to my overall sound. I can still appreciate my original scooped sound, but I need to feel the ground shake when I hit a chord. It hasn’t been any radical change in gear as much as it’s been a change in EQ. For Death Magnetic I used what I always use, which is my standard touring rack, which is filled with some Boogie stuff and a Marshall that I’ve had forever. I also used the new Randall amp that I helped design, and Greg Fidelman, our engineer, turned James and me onto Ampeg heads. Ampeg made incredible guitar heads in the early Nineties and then stopped. And I don’t know why. The one we used had a nice clean, warm sound, and it blended well with the other amps that were in the studio.

I’m a total vintage freak and would have liked to use more of my collectible amps, but we got the sound that worked for the sonic context, and I really didn’t want to make it more complicated. The same goes for guitars. I used a few vintage guitars here and there. I think I used a ’58 Paul and a ’59 Tele on some clean stuff, but overall, almost everything is done on my ESP Mummy and the Caution guitar, which is the original “Skully” [KH-2 Kirk Hammett signature] guitar—the very first ESP guitar, from 1987.

When you do your solos, do you get input from the other guys?

Lars helps me, because when I’m doing solos, it’s hard for me to be objective. I’m a soloing machine! On one song, I played over 100 solos. And when I play more than five or six solos, it’s hard for me to be objective. So Lars helps me out, and he’ll often tell me what’s working and what isn’t.

It’s good, because what he’s really doing is he’s pushing me and inspiring me to go into directions that I wouldn’t think of because I’m too in the moment. For the most part, I’m very much a team player. I like to hear what other people have to say, provided they’re qualified.

What do you think that you learned from St. Anger?

I was shocked by how much people missed guitar solos and my playing on St. Anger. I just thought it would be water off their backs, and it wouldn’t be that big of a difference. On tour, however, at least five people would ask me every single day why there weren’t guitar solos on the album and if there were going to be guitar solos on the next album. To tell you the truth, I had no idea that people considered that aspect, or that ingredient, to be such a large part of our overall sound. I always saw myself more as icing on the cake. But goddamn it, man, those people really like that icing!

I’ve learned that there’s a signature Metallica sound, and if we stray too far from that, our fans get impatient, or they just don’t understand, or they miss the point. And I’m not saying that’s a good thing or a bad thing; it’s just something we have to contend with.

It’s a sound they can’t get from anyone else.

There is some truth there. In the Nineties, we probably spent too much time deconstructing that sound. We did it intentionally, but we oversimplified. Along with that oversimplification came whatever was influencing us at the moment. But I agree with you. You can’t really get Metallica anywhere else but from us, and I think people got the impression that we were just holding back.

I can understand how any band could get bored with doing one thing. You have to be able to go someplace else creatively.

I wouldn’t say we were bored as much as we were restless. We had put out four or five albums using, basically, the same sort of approach, and we were wondering what else we could do and what else we were capable of. We very consciously tried to stay away from certain elements of our sound—like heavy chugging on the E string. There’s none of that on Load, because we felt we had exhausted it.

Were you afraid of becoming a caricature of yourself?

There are bands out there that put out the same album every time and just change the lyrics. We all know who those bands are, and we were very careful to not let that happen to us. In retrospect, we might have overreacted. But now we’re ready to embrace our roots again, and we’re having fun. These songs are really fun to play, and at the end of the day, that’s the most important thing.

And who knows, if you hadn’t taken those turns, people might have been bored with the band by now.

We wouldn’t be as well regarded because we would have diluted our sound with a bunch of regurgitated crap. We’ve never been known to take the easy way out. [laughs] Never. It’s just the way we are. It’s the way we think.

It’s interesting that you would be surprised that people would miss your soloing. You were, after all, the first person inducted by our readers into the Guitar World Hall of Fame. That was over Jimi Hendrix and Jimmy Page.

It’s crazy. Guitar playing is both extremely easy for me and extremely difficult for me at the same time. Today, someone told me that they played guitar, but they “just couldn’t get that soloing thing down.” And I just said, “Bro, I’ve been playing for almost 30 years, and the guitar is still a mystery to me. I’m still searching and finding little things here and there.”

It feels like an unraveling process. I’m unraveling the guitar, and I want to find the core of it, but it’s so multi-layered that I’m not even close.

I think people maybe identify with your sound because of the struggle to some degree.

I don’t have a clear answer to that question. I’m too close to it. One thing I’ve noticed over the years is that young players—I mean 10- and 12-year-olds—really like my guitar style. There’s something in my guitar style that they totally can latch onto and learn quickly, and then go from there to your Yngwie Malmsteens or your Steve Vais or whatever. On the flipside, the more mature musicians hear my stuff and go, “Eh, whatever.”

I think one of the hallmarks of your solos is that they are memorable, which is more difficult than just playing fast.

That’s always been my thing. I love Michael Schenker because he plays the hookiest solos. I’ve always been attracted to players who are not necessarily melodic but very hooky. Ritchie Blackmore has a very hooky style, and he’s not very melodic at all. A lot of times, the stuff he plays comes out of left field, but it’s catchy, and there’s an integrity to it that just kind of pulls at you.

- From the very beginning, I’ve always put taste, phrasing, tone, melody and hookiness before speed and pure technicality. I’ve always played for the song, and I’ve always played to entertain people. And I’ve never purposely played anything to alienate people.

- When you play a great lick that you haven’t played before, it’s amazing, because it feels like it’s been handed down to you from the heavens. It flows through your fingers, onto the strings, to the pickups and out the amp, and suddenly you hear this great thing. You recognize it as the entire creative process. And sometimes that happens so quickly and so unexpectedly. It’s as if there’s a big crack in the ground and this big hairy paw hands you this heavy guitar riff. There are no preconceptions, no premeditations. I’m sure it happens to most dedicated musicians. It may not happen as often to the casual strummer, but if your heart is into it, it happens.

How do you account for this?

I’m way into the metaphysics of the subconscious and multidimensional thinking. I know that vibrations connect all of these things. And if you really want to get technical, I buy into the string theory of physics. The basic principle is that everything in the universe is made of these vibrating strings. It’s nice to think that the cosmos is essentially a huge guitar and inspiration comes when I’m tuned into it.

Speaking of connections, it’s well documented that Metallica went through some tough times regarding your relationship to one another during the making of St. Anger. Do you guys feel reconnected?

Totally. The communication is as good as it’s ever been. Before St. Anger, and at certain times while we were making the album, our camaraderie fragmented to almost nothing. You can almost say that St. Anger was the struggle to get that camaraderie back, but now we have it again, and it’s evident on all levels—on a performance level, on a personal level and on a creative level.

Sometimes you have to strip everything down to basics in order to build it back up again.

Or maybe burn it down. Metallica is like the phoenix rising from the ashes. We set everything on fire, and this is what has risen from it—St. Anger being the fire and Death Magnetic being the phoenix.