Huey Lewis and the News’ Chris Hayes: “Am I an unappreciated guitar hero? Probably. But that’s OK”

Chris Hayes can’t get away from his old band. No matter where he goes or what he does – he can be out for a drive or watching a movie, or maybe shopping at the supermarket – he’ll hear one of their tunes.

Sometimes it’s I Want a New Drug. Other times it’s The Power of Love or The Heart of Rock & Roll. There’s lots more – Workin’ for a Livin’, Heart and Soul, If This Is It, and on it goes. It’s almost as if The Best of Huey Lewis and the News is on constant rotation in the ether.

Hayes isn’t complaining. “It’s always exciting whenever I hear one of our songs,” he says. “When they play your music at the supermarket, you know you’ve arrived – they only program stuff that people want to hear. They used to play Muzak versions of our stuff, which was kind of weird. But now that Muzak’s gone, they play the original recordings.”

The guitarist claims not to have a favorite, but he does admit to feeling a particular thrill whenever he hears his shotgun-like slide of the riff that kickstarts I Want a New Drug.

“I’ll be in a store and I’ll hear that opening part, and it’s like ‘All right!’” he says with a laugh. “The funny thing is, I’ll be standing right next to somebody who doesn’t know who I am at all. And that’s fine – I don’t have an ego about that sort of thing. I just like hearing the music. It really holds up.”

Throughout the 1980s and into the ’90s, Hayes had a dream job. As lead guitarist for Huey Lewis and the News, he was part of a hit-making pop-rock machine that dominated radio airwaves and MTV like few other acts.

He joined the San Francisco-based band in 1979 at exactly the right time for all concerned. During much of the ’70s, singer and harmonica player Huey Lewis led the pub rock group Clover, who relocated to the U.K. and released a series of albums that went nowhere (without Lewis, the band backed up Elvis Costello on his 1977 debut, My Aim Is True).

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Returning to the States, the band (which also included keyboardist Sean Hopper, bassist Mario Cipollina, drummer Bill Gibson and saxophonist-rhythm guitarist Johnny Colla) rechristened themselves Huey Lewis & the American Express and pursued a more commercial direction. To complement their new sound, they sought a suitable lead guitarist.

“I got really lucky,” Hayes says. “I was playing in a few bands and was scraping by. I lived next door to this lady who said, ‘I know this guy who needs a guitar player. Are you interested in auditioning?’ I said, ‘Hell yeah!’ I was looking for jobs. I went in and met with Huey, and as I was playing I remember looking down at my fingers the whole time. Huey said, ‘He plays really well, but we’ve got to work on his image.’ I wasn’t much of a performer at the time.”

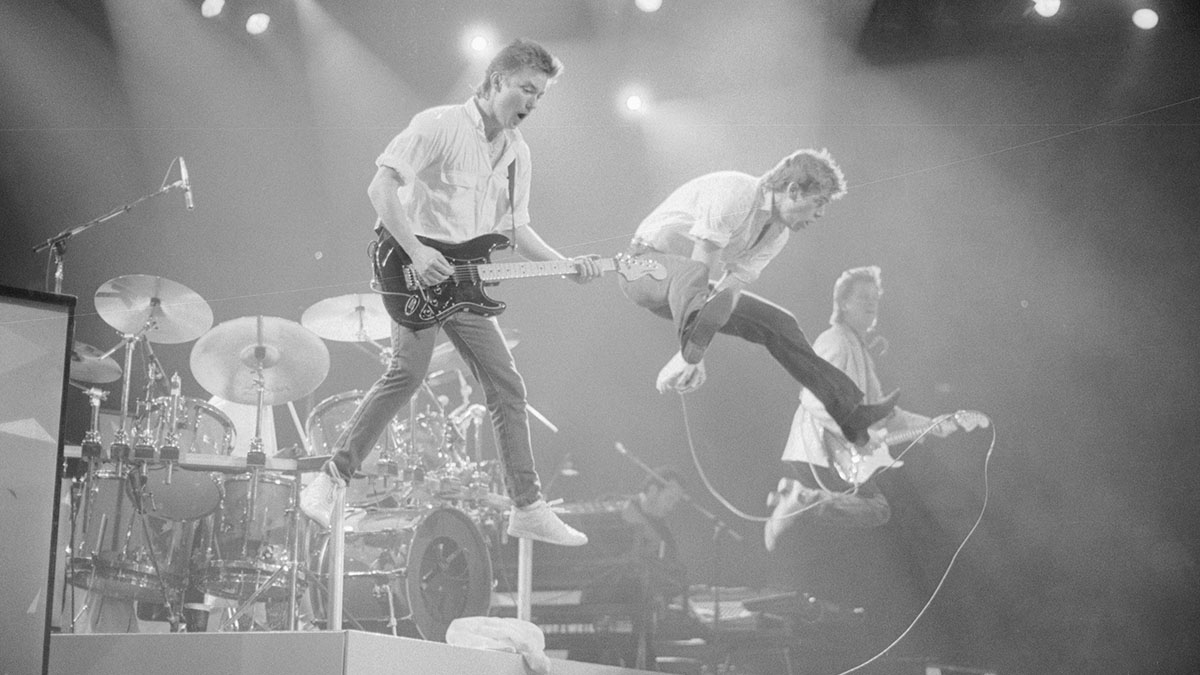

Hayes’ energetic stage persona came together as the band – now known as Huey Lewis and the News – evolved from hard-charging bar rockers into mainstream radio giants and multi-platinum monsters (the band’s 1983 album, Sports, sold more than 7 million copies).

While adding insanely catchy riffs and punchy, adventurous solos to the group’s rapidly growing number of knockout hits, he also proved to be an ace songsmith. Among the tracks that bear his name are Workin’ for a Livin’, I Want a New Drug and the Oscar-nominated The Power of Love (written for the blockbuster film Back to the Future, it was the first of group’s songs to hit Number 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100).

“That was just a magical time for us,” Hayes says. “We sold out two nights at Madison Square Garden, and then we were nominated for an Oscar.” He laughs. “Richard Dreyfuss sat next to me at the Academy Awards ceremony. I tried to say something to him, but he ignored me. Other than that, it was incredible.”

By the 1990s, the group’s once reliable grip on the charts began to weaken, and with the rise of grunge and hip-hop, their sleek sound fell out of favor. The band continued to tour as their album releases grew spotty, but by 2001 Hayes decided to call it a day.

“My motivations for leaving were personal,” he says. “I had a son who I didn’t see that much because I was traveling. Then I got a divorce and stopped drinking – things had gotten out of hand. When I hit 42 and started a new family, I decided I wanted to be present for my children. Being on the road with a band is no way to raise kids. It was time to change everything, so I did.”

My motivations for leaving were personal. I had a son who I didn’t see that much because I was traveling. Then I got a divorce and stopped drinking – things had gotten out of hand

In the ensuing years, Hayes has laid low. He and his wife, Cheree, divide their time between homes in Reno, Nevada, and Springfield, Oregon. When he gets the itch to pick up the guitar, he does, but mostly he fishes. He has no sordid road tales to tell, nor does he have a bad word for any of his ex-bandmates.

“I love them all,” he says. The likelihood of him ever rejoining the band, even for a brief tour, has less to do with him and more to do with the state of Huey Lewis’ health – in 2018, the singer revealed that he was suffering from hearing loss due to Ménière’s disease, and since that time the band has been off the road.

“The situation with Huey’s hearing is really unfortunate,” Hayes says. “But you know, if he called me tomorrow and said, ‘My hearing’s better. Do you want to do a reunion?’ I’d probably say yes. I like Huey. He’s a great friend. We talk on the phone about fishing – we have that in common. It’s so funny. Back in the day, we talked about music. Now it’s fishing.”

Your playing is heard all over the world, even now. Bar bands play your licks. Yet when people talk about notable guitarists of the ’80s, they don’t mention you.

“No, I guess they don’t.”

You’re unsung, underrated.

“Am I sort of an unappreciated guitar hero? Probably. But that’s OK. With everything I’ve been given in this life, I’m not unhappy about that at all. I’ve had success and I don’t need to prove anything to anybody. I could list lots of great guitar players that nobody knows.”

You were a straight-up jazz guy before joining Huey Lewis and the News. Who were your influences?

“I used to be a real jazz snob. That’s all I listened to, and I thought everything else was inferior. In some ways it is, but I don’t dwell on that. [Laughs] I was big on Larry Coryell, Allan Holdsworth, Larry Carlton – those were my guys. Mike Stern blew me away. I was way into John Scofield. That’s the level I aspired to.”

I learned a lot from Huey. He got me to start performing more, got me into putting on a show and jumping around. He built up my confidence

So what was it about Huey Lewis’ band that appealed to you?

“I just kind of fell into it. I was living in San Francisco and was in something like five bands at the same time. We’d play gigs for 50 bucks, and we’d have to split that. I was playing almost every night of the week, but it was still hard to get by. I did weddings – whatever I could do.

“Huey and the band were going places, so it felt like a good situation. I learned a lot from Huey. He got me to start performing more, got me into putting on a show and jumping around. He built up my confidence. I give him a lot of credit for that. He changed my onstage persona.”

The jazz snob thing began to melt away…

“[Laughs] Not really. It was still there, and it’s there today. I’m not an elitist, but I always had my preferences.”

Sure, but the songs you wrote for the band don’t sound like they came from somebody who was faking it.

“Oh, no. I was always looking to do things that were out of the ordinary, although people would say the songs I wrote weren’t that complicated. But you know, who cares? I was trying to inject some of my knowledge into pop songs. I wanted to bridge a gap.”

Everything we did on that first record was unbearably fast. It sounds like we were on meth or something

One of the first songs you co-wrote was Change of Heart. It almost sounds like a new wave song of the time.

“It does, yeah. That was for Picture This, our second album; our first one didn’t do so well. Yeah, it sounds new wavey, but it’s also got a Motown-like chorus. I actually had to change the verse around because it sounded too much like a Motown song. I wasn’t going for new wave at all, but it does have that energy.

“Everything we did on that first record was unbearably fast. [Laughs] It sounds like we were on meth or something. We evolved away from that on the second record. That one had the Mutt Lange song Do You Believe in Love, and that got on the radio. It opened the door for us, and then people started playing Workin’ for a Livin’.”

I was going to mention that one. Did it feel like a radio song to you?

“Huey gave me some lyrics and said, ‘Write me some music to this.’ So I did – I sat on the couch with my ES-330, and I banged it out in an hour. And it kind of sounds like it. [Laughs] It’s pretty infectious, though, and people still like it. It’s actually my most covered song. Three country artists have covered it.”

OK, that riff to I Want a New Drug – how did it come about? It’s a basic rock ’n’ roll pattern, but you mixed it up with such flair.

“Thanks. I kind of fashioned it after Workin’ for a Livin’. That song was something of a success, so I said, ‘I’m gonna write a song like it.’ I came up with that bouncy guitar riff, and that was that. It was actually super-easy; it came right out.”

You got a dynamite guitar sound on the recording. What did you use?

“I used a Les Paul and a 50-watt Marshall through a 4x12 cab, cranked all the way up.”

You do a pretty long-ass solo on the song, and on the album version you reference Purple Haze. How much leeway did Huey give you on solos?

“Huey was great. He gave me a lot of leeway on solos. That one in particular was a lot of fun. That was always my favorite part of recording, when we were done with basic tracking. Huey and I would go in, and he would produce me. We just got along.

“The other guys would produce me sometimes, but I preferred working with Huey. He always ‘got’ me. He knew what he wanted out of me, and he did it in a very gracious way. A lot of times we’d try a guitar solo, but sometimes we’d listen to it and go, ‘No, it needs the sax there.’”

After you started having hits, did you feel pressure to keep them coming? Like when you were asked to write something for Back to the Future...

“I guess it was pressure, but I didn’t feel it, meaning I didn’t let it get to me. When somebody says, ‘I need you to do this,’ it makes me want to do it. I remember they were looking for a song for the movie, and I said, ‘OK, I’ll give it a shot.’

“That’s how The Power of Love came about. I knocked out the guitar riff, and the rest of the song came together. I demoed it up with Johnny Colla. He made a couple of edits, and that was that. We submitted it and they liked it.”

Your solo in that song starts out with an Albert King bend by way of Stevie Ray Vaughan. Am I in the right lane?

“Oh, you’re in the right lane. At that time, Stevie was opening up shows for us. He was on the road with us for a year and a half. We spent a lot of time on the bus together. Stevie was great. One night, he kicked the rest of his crew out of his bus, and it was just the two of us drinking Crown Royal and talking about music. I used to watch him on stage and think, ‘I wish I could play like him.’

Stevie Ray Vaughan was so strong. When he shook your hand, he would crush it. He had the hands of an auto mechanic. He put that into his playing

“He was so strong. When he shook your hand, he would crush it. He had the hands of an auto mechanic. He put that into his playing. He used super-thick strings, and those bends he did… I couldn’t play his guitars because I didn’t have the strength. He was amazing. He could get sounds that didn’t exist. So yeah, did I reference him on that song? Sure I did. [Laughs]”

How democratic was the band? Did you have a major say in what went on?

“Very much so. The band was very democratic. Yes, it was definitely Huey Lewis and the News. He was the benevolent dictator – although I don’t like to use that word. He listened to what everybody said. He could be tough, but he had to herd cats, and it wasn’t always easy.”

Was it Hip to Be Square?

“[Laughs] You know, I thought that song was a little weird, but it kind of grew on me. Now I actually like it. The video we did was killer. It’s the kind of song that they like to put in commercials. It’s had a life. The lyrics are a little cutesy, so I can see why some people are turned off. It took me a while to say, ‘It’s a good song.’ Maybe it’s because I’m old now. [Laughs]”

The band started to get more bluesy and less pop oriented in the ’90s. Was that a tough period for you? Radio had turned away from your sound.

“It was tough, sure. Things had changed, radio was changing. We were being told by the record company that electric guitars were out. They wanted things very poppy and light.

“We did the song Couple Days Off, which is like a fusion song, and we had to remix it and put acoustics on it. I was like, ‘Wait a minute. They’re erasing who I am.’ It wasn’t a great time for guitar players, unless you were in a metal or grunge band.”

What kinds of guitars were you using throughout your time in the band?

“My late-’60s Les Paul goldtop was a real favorite. One of our lighting techs dropped it. He didn’t tell me, and he put it back on the stand. I went to grab it and the neck just snapped. I was like, ‘What the hell?!’ I needed a new guitar, so I bought a ’68 black Les Paul Custom. I used a bunch of guitars.

“My rhythms were mainly done with Strats because they have that tight sound that fits in a mix. I didn’t use Les Pauls for rhythms because they have a midrange that can take over a mix. For solos, that’s fine, but not for rhythm tracks. Although for the solo in The Power of Love, I used a ’57 Strat, and that came out great.”

You mentioned how your life had spun out of control toward the end of your time in the band. Drinking was a big issue?

“That was an issue, sure. I became a Christian, and drinking just wasn’t conducive to my lifestyle. On the road, I found myself drinking when I didn’t even want to. I’m not bagging on people who drink, but for me, it wasn’t working anymore. It was fun while it lasted. [Laughs] I certainly had lots of fun, but after a while you have to decide when enough is enough.

“I spent about five years touring with the band, and I was completely sober. That was a little strange – everybody’s having a blast and getting hammered, and I’m drinking water. And then I went back to drinking after being sober for five years. That’s when I said, ‘If I keep doing this, it’s not going to get better.’ I left the band for personal reasons. It had nothing to do with the rest of the guys.”

Is that time of your life in the rearview mirror, or does it feel like yesterday?

“It feels like yesterday. But a lot has happened since then. I’ve raised a family and have been to a lot of soccer games. I think I left the band at just the right time. Careers in music have definite periods, and unless you’re one of the few exceptions, like Billy Joel, as you go on you’re going to be in smaller and less prestigious places. That just wasn’t for me.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“I suppose I felt that I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I’d put into it. My head was huge!” “Clapton is God” graffiti made him a guitar legend when he was barely 20 – he says he was far from uncomfortable with the adulation at the time

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul