“It’s a primal, unconscious reaction. An honor bestowed upon only the best riffs”: What’s the science behind a stank face riff? We asked everyone from Mike Stringer to Periphery and Nik Nocturnal to define metal guitar’s ultimate accolade

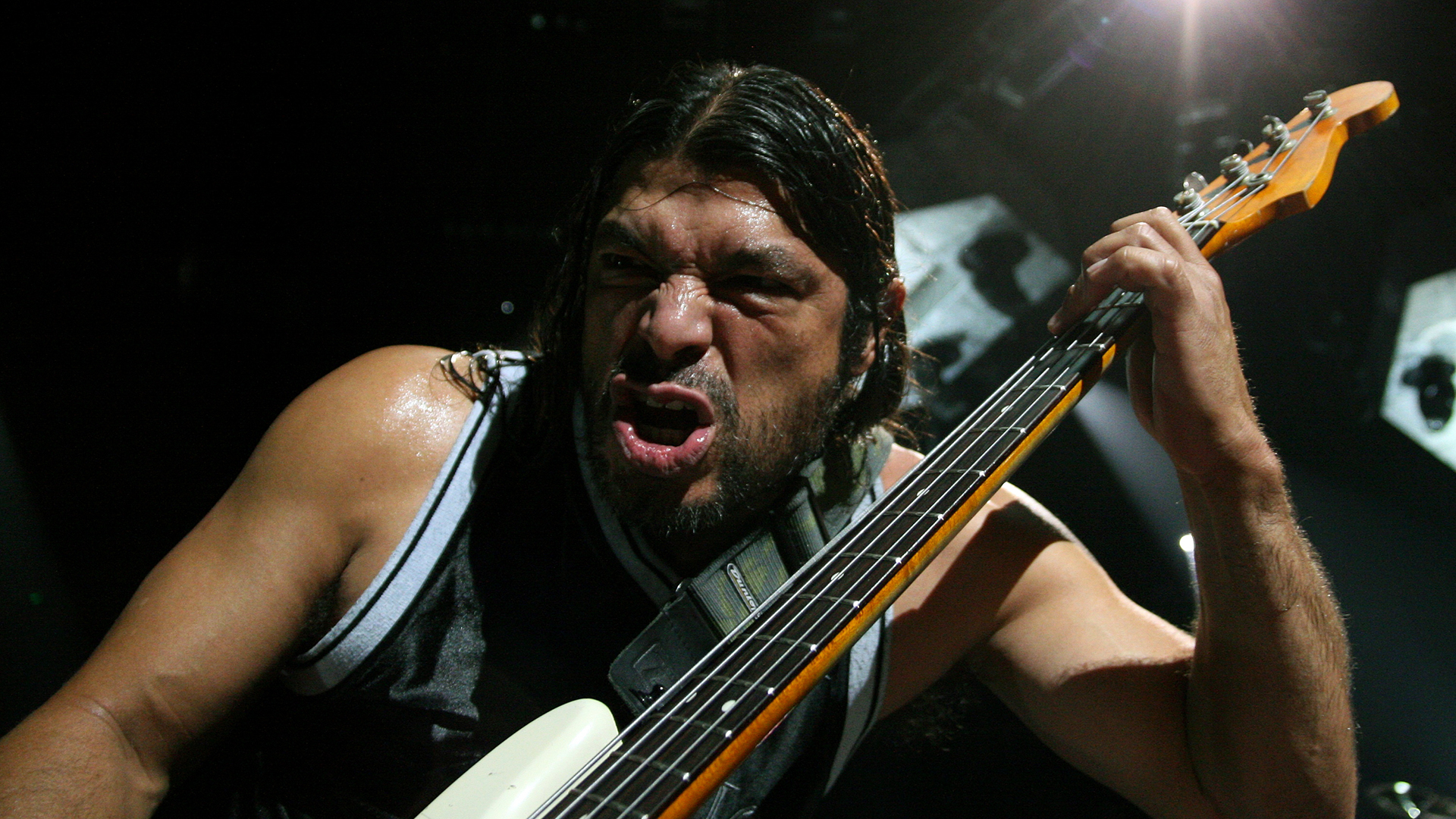

Contorting a listener’s face in loving disgust is the highest compliment a metal musician can receive – but what makes a great stank face riff? We set out to discover the secret sauce…

When Taylor Swift wrapped up the US leg of her Eras tour in Los Angeles last year, she received a mammoth eight-minute standing ovation. Metalheads, however, have a rather different way of showing their appreciation. Conjuring a stank face with riff is something Spiritbox’s Mike Stringer says “can be one of the highest forms of praise.”

You know the expression: all contorted like you’ve just popped the world’s most sour piece of candy in your mouth. It’s a phenomenon seemingly exclusive to the metal genre and its nastiest riffs. But why do we react in such a way, and what are the secrets to creating that reaction?

The science of stank face

According to British music academic Milton Mermikides, there’s scientific reasoning behind a response which, in other styles of music, may convey the complete opposite meaning.

“Stank face is perhaps just a modern term for a long-documented musical experience which falls somewhere between deep visceral pleasure and a sort of physical engagement, irritation or even repulsion – an ecstatic ‘pleasurable pain,’” he says.

In the writing room, stank faces are the nexus of our language because they’re non-verbal

Mark Holcomb

“It relies on music’s unique ability to trigger a host of physical and emotional responses in the listener. These include our response to dissonance, such as the roughness of a sound – a scrunchy chord, an angular melody or a syncopated rhythm.

“When coupled with the dopamine release from satisfying predictions and bodily engagement, these can produce ‘cross-modal’ responses. It’s as if the music is so rich, flavoursome and satisfying it bleeds into our other senses. Not only do we hear it, we can almost taste and smell it – hence the characteristic facial and bodily responses.”

Non-verbal communication

For Periphery’s trio of guitarists Misha Mansoor, Mark Holcomb and Jake Bowen, it’s also a form of communication. “Sometime it just takes a few seconds of hearing a riff and the face appears; no words need to be said,” Holcomb says. “In the writing room, stank faces are the nexus of our language because they’re non-verbal.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It’s like a reflex,” Mansoor adds. “It’s one of those things that you react to and then you think about.” Importantly too, it’s a way of communicating appreciation – a primal, unconscious reaction and an honor bestowed upon only the best riffs.

“I remember Plini and Tosin Abasi coming over to hear a demo of Wildfire,” Holcomb says. “It was when that second riff comes in; I remember looking at their faces to see how they honestly felt about the music. When you get that stank face reaction from someone you respect, as silly as it sounds, it holds a lot of weight.”

Hooks

As filthy as stank face riffs need to be to twist a listener’s face, the value of a hook shouldn’t be overlooked.

“Hooks contribute to heaviness in a way that people don’t expect,” says YouTuber and guitarist Nik Nocturnal, who’s learnt a hell of a lot from his Heaviest Riffs video series. “Take a band as extreme as Knocked Loose; people will listen to those riffs and think it's just 2-3-1-0 with dissonant notes.

“They don’t realize that even though it sounds so caveman, it’s still a hook. Everything is chromatic and dissonant, but it’s a rhythmic hook that gets stuck in your brain.”

Mike Stringer echoes that sentiment. “It’s obviously all situational, but you’re usually playing off of a melody,” he says. “I think if you can have the listener hum along to the riff, and have it stick in their head, you’ve done a great job. It might be metal, but it still has to have a hook. You have to give the listener something to grab onto.

“The riff is the foundation of the song, and grooves and hooks are what give it life, so having those memorable groovy riffs is one of the most important parts of writing a metal song in 2024.”

Simplicity vs. complexity

Holcomb says rule number one is that “stank face riffs can’t be too notey. It needs to have a Neanderthal element to work.”

Enterprise Earth’s disgusting riff machine Gabe Mangold agrees with the caveman argument: “Stank face is a feeling; it’s not a tangible thing – it has to induce some sort of primal feeling within you. The way the tone of your guitar is coming out of your hands is very important. If you’re palm muting, you need to be hitting the strings in a certain way; the low end needs to be blooming.”

Stringer adds: “It all comes down to what the overall goal of that song is. When I was younger I used to be very concerned if a song I wrote was too easy to play. I’d try to cram as many notes in as I could – that’s not rational thinking. If a filmmaker utilizes a ton of CGI, that doesn’t mean it’s going to be better than the slow-zoom Stanley Kubrick shot. We’ve all seen The Hobbit!”

If you play the stanky stuff all the time it loses effect… it’s like candy; it’s always best if you’ve had to wait a while

Tor Oddmund Suhrke

For Leprous’ eight-string Aristides-wielding guitarist Tor Oddmund Suhrke, streamlined writing needs to be combined with “a little X factor that makes it stand out – like a long slide, a slow bend or some dissonance which helps give you that physical reaction to the sound waves.”

He continues: “It can definitely send shivers down my spine, but not in an uncomfortable nails-on-a-chalkboard way. It can add a good kind of filthy in an otherwise technical and tidy soundscape.”

Nocturnal says: “It’s all about how you deliver those riffs and finding that balance of rhythm and melody. Take Bleed by Meshuggah – it’s one note, but it’s one of the chunkiest, hookiest riffs in the whole world.

“Generally, the more notes or rhythms, the harder it is to control. But if you can control the chaos in either direction and find a balance, you can make the heaviest music in the world and it’ll throw down.”

Does tuning low guarantee heaviness?

Both Stringer and Nocturnal are eager to point out that, contrary to the belief of some, drop tuning a riff isn’t a cheat code for guaranteeing heaviness.

“If you rely on down tuning for impact every time, you’re going to have a bad time,” says Stringer, believing that it’s a technique to be used “sparingly.”

Nocturnal adopts a more technical outlook: “The lower you go, the more frequency ranges you’re exploring. Keys are all relative – it doesn’t matter if a song is in drop C or B; it’s more how the frequency ranges change when chugging that low string, and people’s preferences to those ranges.”

Context

The bigger picture is important, too. This includes a song’s structure, production, and how other instruments play off of a riff.

“It’s something I’ve noticed doing so many videos,” says Nocturnal. “I’ll isolate a riff and sometimes I’ll be like, ‘That’s not really a heavy riff.’ People have the misconception that it's just the guitar that contributes to the heaviness, but the drums, vocals, and production are just as important.

“With Mick Gordon’s Rip and Tear, it’s the pumping drums and the synths going wild that makes it demon slaying music. Otherwise, it’s just a cool riff.”

Leprous are lucky to have one of the world’s best modern metal drummers in their ranks in Baard Kolstad, who has “a very important role when it comes to stank face reactions from the audience,” says Suhrke.

“It’s good to have a versatile drummer who can handle so many different grooves, because if you play the stanky stuff all the time it loses effect,” he adds. “It’s important to relieve that feeling. It’s like candy; it’s always best if you’ve had to wait a while for it – if it’s there all the time it gets boring.”

Music is relative – there are some people who unironically love St. Anger

Mansoor says: “If you’re trying to craft a stank face you wanna build into it. It’s more about the section that leads into it and what choices you make at the end of that – does it have a cool fill or a stop so that when it hits, it really hits?”

“It all depends on the canvas,” Stringer believes. “Ambience and bringing back overall themes can really push a heavy part. If I’m writing something with a recurring melodic theme, I know I can usually bring that over the heavy part and use what was a melodic theme as dissonance.

“I also love experimenting with samples and synth layering, sending them through pedals to get unique results and putting it overtop of riffs. That can bring some very cool results.”

As Suhrke points out, sometimes it can be a case of saving your stank face trump card until the very last moment.

“The ending of The Sky is Red – which I feel is maybe one of our creepiest sections – hasn’t been hinted at earlier in the song,” he says.

“So when it comes, it gives me a very visual thought of something creepy unknown rising, starting with that small sound which then builds and builds to a very epic structure.”

Of course, there isn’t a failsafe trick to create a stank face-inducing riff every time, and that’s part of the magic of it. Music is relative – there are some people who unironically love St. Anger. But one important thing to take away is that stank face riffs can come in all shapes and sizes.

Says Nocturnal: “We live in a world where Knocked Loose, Vildhjarta and Sylosis can all write the heaviest parts, and they all come from very different worlds of metal and play in very different tunings. It’s fair game.”

A freelance writer with a penchant for music that gets weird, Phil is a regular contributor to Prog, Guitar World, and Total Guitar magazines and is especially keen on shining a light on unknown artists. Outside of the journalism realm, you can find him writing angular riffs in progressive metal band, Prognosis, in which he slings an 8-string Strandberg Boden Original, churning that low string through a variety of tunings. He's also a published author and is currently penning his debut novel which chucks fantasy, mythology and humanity into a great big melting pot.