How Taylor devised its new Grand Theater acoustic body shape

Taylor’s new acoustic outline is a bold step. We talk to designer-in-chief Andy Powers to get the full story behind it

Taylor’s new GT 811e is a bantamweight instrument that packs a surprisingly potent punch, but, maybe more importantly, it’s loads of fun to play.

Smaller-bodied instruments notoriously lack an even frequency response and often have a hole where the bass should be, but that’s far from the case here. The fact that it plays and responds so well is down to the craft of its designer, Andy Powers – who joins us to talk us through the process.

Where exactly did you start with the new Grand Theater body size?

“It was string length, actually. A lot of time in the world of guitars we think of designing the body size or body shape first and we think of the string length as a secondary consideration. In this case, I wanted to start with a scale length that falls in between your more typical 25-something inch scale length and what you’d think of as a more travel guitar scale length that’s 23.5 inches and smaller.

“If you take a typical 25.5-inch scale length that’s common for, say, a Fender and were to drop-tune that to Eb you kinda get this appealing slinky, easy-feeling guitar, right? A lot of electric guitar players do that. I don’t always do it, but I enjoy the feel of it. But I don’t necessarily want to play drop-tuned. So, to get that same feeling you could capo up one fret and then you’re back at concert pitch, but you still have this really nice slinky feeling.

“The other benefit that I get when I do that is that I have a little smaller space between each fret; it’s a little easier to get around, easier to make those chord stretches. So I took that resulting scale length, if you will, and designed the whole guitar around that setup. Because we’re using a typical size set of strings and have voiced the guitar appropriately for that slightly lower string tension, the thing ends up working really well – that easygoing feel that we like so much.”

Sometimes we want to go to the more esoteric details of the guitar and talk about the nuances and the subtleties of this and that, but the mere physics of the guitar matters a lot

That’s a really interesting approach to designing a body size…

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Sometimes we want to go to the more esoteric details of the guitar and talk about the nuances and the subtleties of this and that, but the mere physics of the guitar matters a lot. The string length, the physical size of the body, the proportions of the body… Because it determines those first big, broad brushstrokes on a design. They determine the way it’s going to go, the way it’ll work out for the musician – the way they’ll hold it, approach it.

“So with the GT design, that Grand Theater body shape with its different proportions, its scale length and whatnot, I find that musicians approach that instrument differently than all the other guitars that they have. Even if you compare it to something like the GS Mini, which is smaller still, your approach is different.”

How about the C-Class bracing?

“In real simple terms, it’s an asymmetrical bracing pattern in order to make an asymmetrical voicing. If you’re familiar with the V-Class idea that we introduced a few years ago and the development that went into that, you can generate a good bit of sustain by using a top that’s fairly rigid parallel to the strings.

“When you go to build volume you need some flexibility, just like a speaker cone; the thing actually has to displace air in order to produce sound pressure. So what I’m always trying to do is balance those two to see how you can get the best result.

The C-Class idea was a way to deliberately over-exaggerate the low-end response from a small box so that it ends up well balanced despite its size.

“Typically, with a very small-body guitar that’s really challenging for a designer because there physically isn’t enough room to allow the top to flex enough to produce what we think of as being a pleasing bass response. It’s hard to make a big fire in a small fireplace. So with some designs, especially with a symmetrical design, you can make a very pleasing voice, but the low-end response is less satisfying.

“That’s why we think of a parlour guitar as having this delicate low-end response. It can have great volume and it can have great clarity, but it’s difficult to get the sort of broad, uniform response out of a mainstream guitar that I could strum chords on, play leads on and accompany things with.

“So the C-Class idea was a way to deliberately over-exaggerate the low-end response from a small box so that it ends up well balanced despite its size. The low-end response certainly isn’t the same as a big dreadnought or something, but when you listen to it and play over the whole usable register of that guitar it ends up relatively well balanced.

“If I were to draw the frequency response like a graphic equaliser, a small-bodied guitar would dip out in the low-end dramatically on the E, F and F# on the low E string. It just falls away. That overall low-end response is missing from the guitar’s register.

“You can always feel that little bit of body behind every one of the notes you play even though the frequency of the note you’re playing is much higher than you would think of as being articulated by that resonant frequency. That’s missing from a small body because you just physically can’t make it that easily. In this case, with the asymmetrical C-Class design, we’re making up for that missing spot by over-exaggerating it.”

The entire philosophy behind this GT guitar was that I want it to be fun to play – make it appealing, make it sound good

What’s the physical make-up of the C-Class bracing pattern?

“If you were to disassemble the guitar and look at it from the inside you’d see very clearly that it’s closely related to the V-Class idea. You’d see where the rest of the V would be, but in this case it’s been modified so that it’s kind of only halfway there. So if you look at the footprint of where the braces go it’s pretty clear as to what’s going on.

“For me, at least, the interesting magic behind the design is in looking at which parts of the guitar you can make strong and which parts you make flexible in order to make that kind of response that we’re looking for.

“The entire philosophy behind this GT guitar was that I want it to be fun to play – make it appealing, make it sound good, but it can’t be a guitar that takes itself too seriously. For me, the measure of merit in an instrument is how much I enjoy playing it. It should be gratifying to play, you know – you should enjoy it and it should make you want to play.”

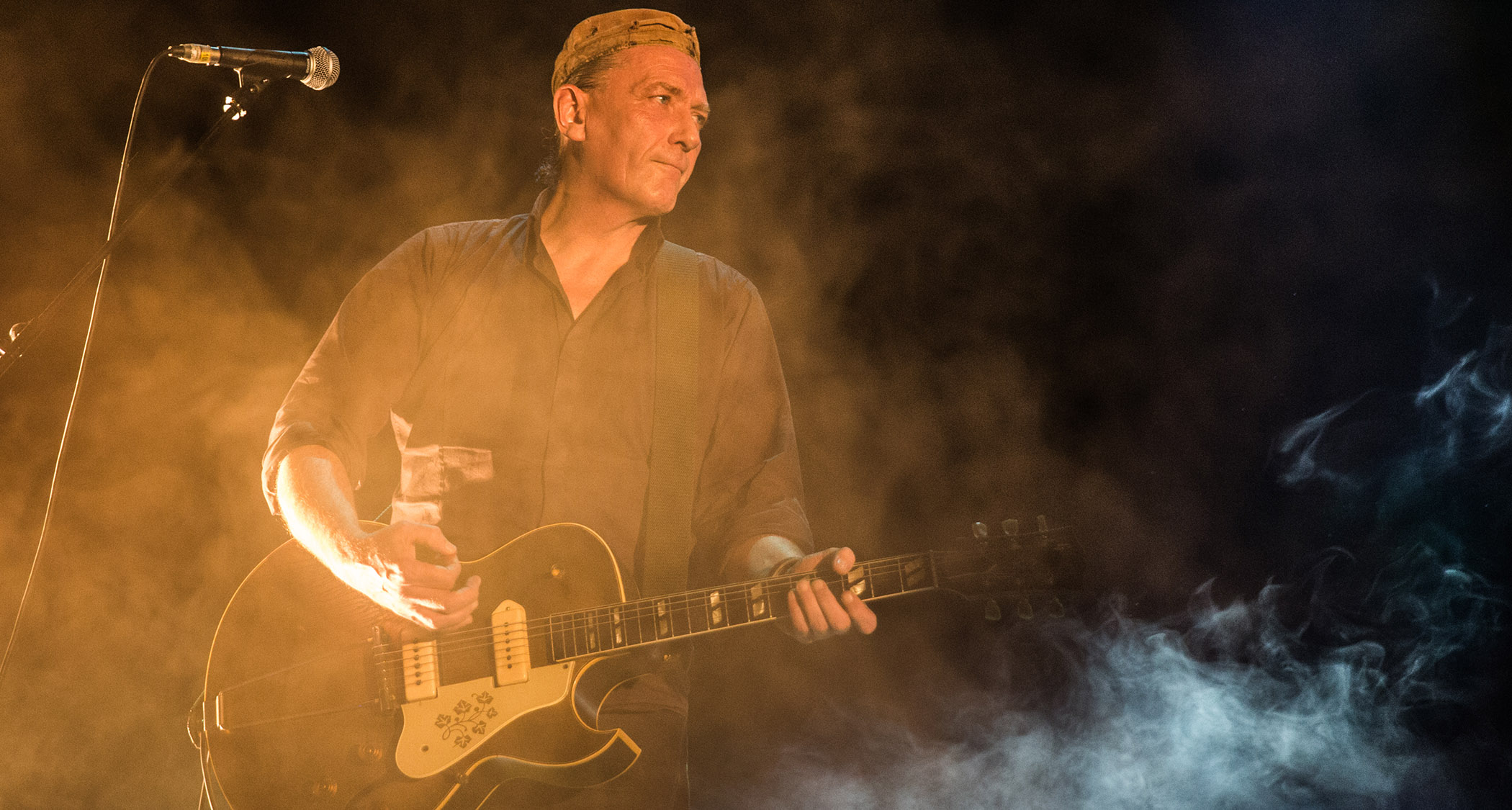

With over 30 years’ experience writing for guitar magazines, including at one time occupying the role of editor for Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, David is also the best-selling author of a number of guitar books for Sanctuary Publishing, Music Sales, Mel Bay and Hal Leonard. As a player he has performed with blues sax legend Dick Heckstall-Smith, played rock ’n’ roll in Marty Wilde’s band, duetted with Martin Taylor and taken part in charity gigs backing Gary Moore, Bernie Marsden and Robbie McIntosh, among others. An avid composer of acoustic guitar instrumentals, he has released two acclaimed albums, Nocturnal and Arboretum.

“Among the most sought-after of all rhythm guitars… a power and projection unsurpassed by any other archtop”: Stromberg has made a long-awaited comeback, and we got our hands on its new Master 400 – a holy grail archtop with a price to match

The heaviest acoustic guitar ever made? Two budding builders craft an acoustic entirely from concrete because they “thought the idea was really funny”

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)