How Barefaced Audio revolutionized the guitar cab

A British company is producing huge sounds from small, featherweight guitar cabs – thanks to the appliance of science

It’s slightly embarrassing that it took a bassist to rethink guitar cabs so they produce a really big sound from a small, lightweight box – but such are life’s little ironies.

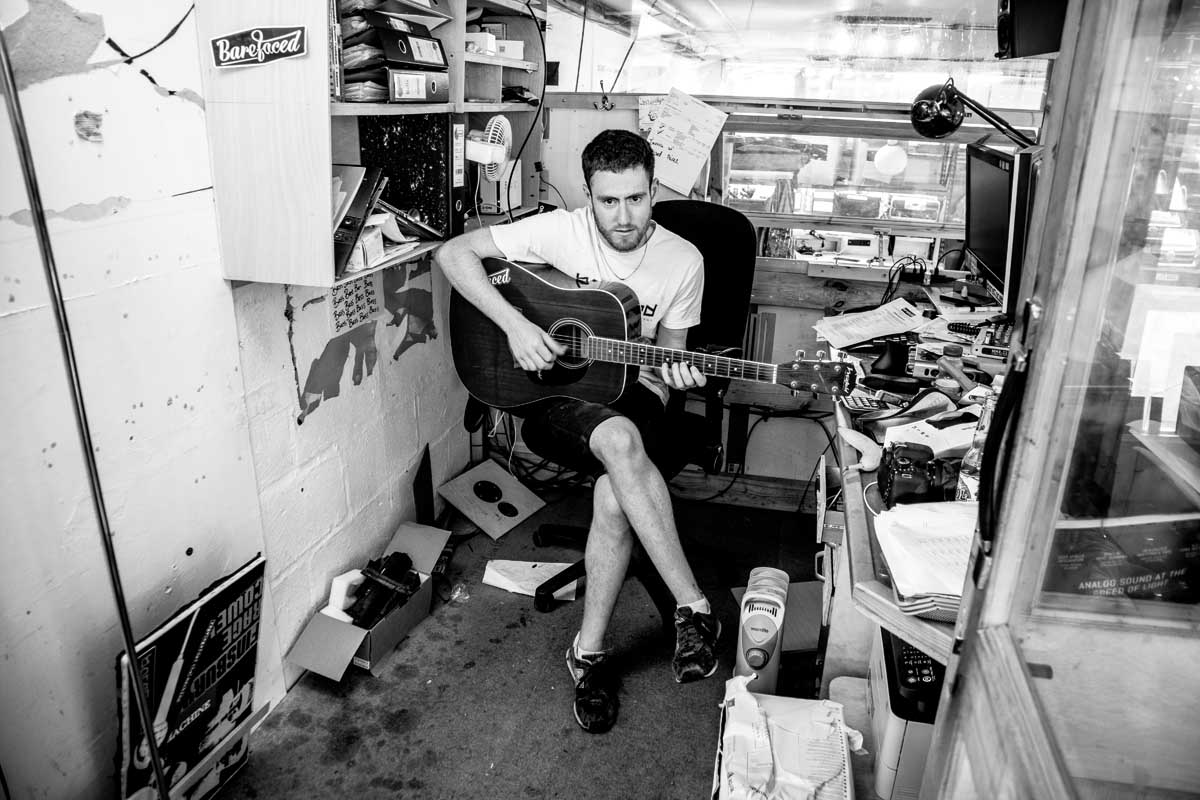

Alex Claber is the founder of Barefaced Audio, a Brighton-based company producing some of the most innovative and intriguing guitar cabinets we’ve seen for a while.

Cleverly designed internals mean the company’s pint-sized Upsetter 110 cabinet, which weighs less than a guitar in its case, produces a room-filling, expansive sound that’s remarkable for such a compact design.

Paired with a small lunchbox head, such as Victory’s V30 The Countess, it forms a rig that can be carried in one trip from the car to the stage without breaking a sweat – yet sounds as big as a hefty combo. It doesn’t rely on neodymium speakers to achieve that light weight, either (though you can have them fitted if you wish), but comes loaded with a Celestion G10 Vintage driver as standard.

The secret to this sonic sorcery is the application of science, says Alex, a bass-playing engineer with a fascination for the more arcane aspects of how sound waves travel from source to ear. His company, Barefaced Audio, began as a kind of serious hobby that blossomed first into a cottage industry and then a thriving business.

Alex cut his teeth in cab design while trying to build himself a better bass cab for his band. Fed up with poor monitoring on stage that meant he could scarcely hear himself play, he decided to investigate new cab designs that would generate a stage-filling sound that could handle the diverse repertoire of music he played, ranging from metal to reggae, without breaking up or losing definition.

“I was basically doing all the things that made bass rigs go ‘Aarggh!’,” he says, wryly. The innovative multi-speaker designs that resulted from his private research proved a hit with the bass-forum members he was sharing ideas with and things grew from there.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

One of the unusual design features he trialled in his early bass cabs was using guitar speakers alongside more traditional bass drivers. This initial dalliance with the world of guitar tone led him to investigate guitar cabinets, too – and he was surprised by the apparent lack of innovation in that world, compared with bass rigs.

“Loads of other companies kept bringing out new cabs, saying, ‘This is the latest, greatest and best yet,’” Alex recalls. “But I kept looking at them and thinking it was just ‘More salt, less salt; more chilli, less chilli…’ They were all variations on an established theme. So I had an idea for a guitar cab that worked better,” he says.

One of the main problems that Alex identified with traditional guitar cabinets is that their typical shape – which is low and wide – was, theoretically, exactly the opposite of what was likely to produce an ideal sound on stage.

“Ideally, you want speaker cabinets to be tall and skinny,” he says. “Because as soon as you make a cabinet wide it narrows the lateral dispersion [spread] of its sound. That’s why all PA stacks are like that these days.”

In other words, the wider the cab, the more narrowly directional its sound is likely to be.

“Most venues are much wider than they are tall,” he explains. “Meanwhile, everyone’s ears are 5ft to 6ft off the ground. So, from the perspective of height, there’s quite a narrow zone where you really need to get sound out. Width wise, it’s a different story: nearly everyone in the audience – and probably the guitarist themself – is standing to the left or right of the cab. So you’ve really got to get the cabinet to spread sound laterally.”

This problem with directionality is made worse by the standard sizes that guitar speakers come in, as Alex explains.

“One of the fundamental issues with guitar cabs is that good guitar tone relies on everything running through a relatively big speaker. If you run a guitar through a [small] hi-fi speaker, it sounds terrible. That’s why you don’t generally get speakers much smaller than 10 inches for electric guitar, because the colouration that larger speakers lend to the tone makes guitars sound nicer. They take off all the sharp edges and harshness and warm things up.

“But the inherent problem with that is that a big speaker has limited dispersion [sound-spreading ability] because the dispersion of any wave, of any sort, relates to the size of the wave versus the size of the source. Basically, if you’ve got a small wave coming from a big wave source, it goes in a straight line. This is why radio telescope dishes are so big – so they can focus a very tight beam.”

So Alex set out to solve this twofold problem of directionality. Tall and thin guitar cabs should, from an engineering point of view, have provided the best answer – raising the speakers nearer to ear level and permitting the amplified sound to spread laterally as much as possible. The problem was few guitarists would be prepared to accept how they looked.

“Tall, skinny cabs look really stupid – after all, you’ve got to put an amp on the top of them,” Alex admits. “At the end of the day, no-one says, ‘I’ve gone to listen to a band,’ they all say, ‘I’ve gone to see a band,’ so there’s definitely a big visual element to it.”

Realising this was likely a dead end, Alex decided to look elsewhere for a solution. He’d long been interested in the ideas of the influential audio expert Siegfried Linkwitz and some of his ideas gave Alex a starting point for a new kind of cab design.

“He was quite an advocate of open-baffle speakers,” Alex explains. “With an open-baffle speaker, you’re not trying contain the sound off the back of it inside a box, because that has its own issues. His idea was like, ‘Well, let the sound out and then do something useful with it.’”

Starting with the problem of the inherent directionality of guitar speakers, Alex decided to see if changing the internal structure of the cab could help guide sound waves coming out the rear of an open-back cab and spread them wider than traditional cab designs could manage.

“I had this idea that if I had a slot on the back of the cab and some [carefully placed] panels, it’d act like a horn,” he says. “Essentially, it’d be an open-back cab with a form of rear waveguide. The design process started off in 2015 with a speaker clamped in a Workmate and two bits of plywood and me waving them about to see how it affected the sound.

“It was just really interesting. If the gap was too wide it just behaved like an open-backed cab. If I made the gap too narrow, all the treble vanished. It was really weird!

“The mids came through but suddenly the treble was blocked by some kind of acoustic inductance. If I moved the outer ends of the panels closer together and made the angle between the panels too narrow, too much like a horn, it went all honky and horrible-sounding. But if I made the angle too wide, the panels did very little to help the sound coming through the slot.

“I discovered there was a sweet spot for the angle to maximise output and dispersion and minimise colouration so it sounded like the output from the front of the speaker.

“So I started sort of messing around with these ideas and I ended up making this prototype cab, which had a 10-inch guitar speaker on one side and a high-efficiency bass 10 on the other. It also had a rotary switch with a crossover [circuit for routing specific frequency ranges to different speakers], the idea being that you could set it to be optimal for the room and style of music you were playing. If you were in a small room, you would just use the guitar 10, and if you were in a bigger room, you’d bring in some extra-low midrange weight and oomph from the bass 10, because they would crossover quite a bit.”

I discovered there was a sweet spot for the angle to maximise output and dispersion and minimise colouration so it sounded like the output from the front of the speaker

Alex Claber

Alex soon realised that this approach resulted in a highly flexible cabinet – but potentially the concept was too elaborate for everyday needs. He needed to keep the big, expansive sound of his waveguide design but make the unit simpler and lighter and compatible with a wider range of guitar speakers.

“At some point, I was pondering this and I thought, ‘Hang on, the side that has got the guitar speaker in it… what would happen if I sealed that, so that that slot with the waveguide in it is basically a weirdly shaped bass reflex port, as well as being this thing that lets mids and highs through?’ So I just started making some more prototypes at that point.”

After a few years of experimentation Alex hit upon what has become the basis of his current guitar cabinets. Looked at from above, the internal layout of Barefaced Audio’s guitar cabs features a V-shaped array of two panels behind the speaker, placed so as to form a slot-shaped aperture where they (almost) meet, a design he has dubbed AVD.

It was always bass players saying, ‘Oh, our band’s guitarist is amazed my bass cab is so light. Can you make him a lightweight guitar cab?‘

This worked strikingly well in producing an expansive sound that also sounded natural and familiar to guitarists. A useful side effect of this was that the AVD structurally stiffened the plywood cabinet, much like the bracing inside Barefaced’s bass cabs.

The larger guitar cabs follow Barefaced’s bass cab designs in having more bracing and reinforcement as needed to be gig-tough, while weighing far less than traditional cabinets.

“People have been asking us for a guitar cab for years, but it was always bass players saying, ‘Oh, our band’s guitarist is amazed my bass cab is so light. Can you make him a lightweight guitar cab?’ But I always said, ‘Well, I don’t want to just make a lightweight guitar cab because there’s this fundamental problem with guitar cabs to solve first, which is that you can’t hear them properly unless you’re standing in the right place in the room, particularly if they’re closed-back ones.’ It was really a case of, ‘How can I solve that first?’ So that’s the path the design went in primarily.”

Alex gave us the chance to try two of the resulting guitar-cab designs offered by Barefaced, the Upsetter 110 and the Reformer 112, and testing them over a few days we found them to be a real ear-opener.

Starting with the little Upsetter, we were surprised by a markedly wider spread of sound than expected from such a compact cube – as well as more ‘air’ in the amplified tone than we were expecting. The single-speaker Upsetter produced a less dense, directed sound than that of our 2x10 Dr Z combo but retained plenty of punch and clarity. It also felt harder to instinctively place where the cab was in the room.

Moving up to the 112 Reformer, we discovered the same spatially expansive qualities but in greater, fuller measure. Both cabs were impressive sonically and, when combined with the AVD design’s secondary qualities of compactness and light weight, made a very compelling case for any guitarist still lucky enough to be lugging gear to gigs.

We would, however, add that the feel and sound of both cabs is a little different from the norm – and some guitarists might either need a moment or two to adjust or decide to stick with tradition, warts and all. Barefaced offers a one-month trial period on new cabs within Europe, though, so deciding for yourself is risk-free.

With the standard models we tested, we felt there was slightly more emphasis on sparkling treble and clearly defined bass than mids, as compared with our test amp’s own speakers and cab. Put another way, the Barefaced cabs made our Fender-inspired Dr Z Jaz 20/40 sound more like a pristine, high-headroom Fender combo than it previously did with its own 210 cabinet.

Note, however, that both Barefaced cabs feature a bass-cut switch that lets you shelve off bass in the same way that good preamp-derived pedals such as Xotic’s EP Booster will do. An excess of bass frequencies is sometimes an impediment to your tone breaking through effectively in a mix, so having that option on a cab will be a welcome feature for many guitarists.

And while we enjoyed the 112 Reformer, our thoughts kept returning to how potent yet compact a rig that combined the 110 Upsetter with a little lunchbox head would be – the ultimate ‘pocket rocket’ setup for small stages or a corner of the living room.

If you get a chance to try either cab, we strongly urge you to do so – it’s richly refreshing to try something new, effective and progressive in a field that’s stood surprisingly still for many years.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.

"This seems like the missing link for anyone who uses an amp modeler at home": HeadRush FRFR-Go speaker cab review

Amps as furniture? This brand of high-end cabinets puts Celestion speakers into luxury furniture inspired by ’70s hi-fi consoles – and aims to blend guitar gear seamlessly into your life

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)