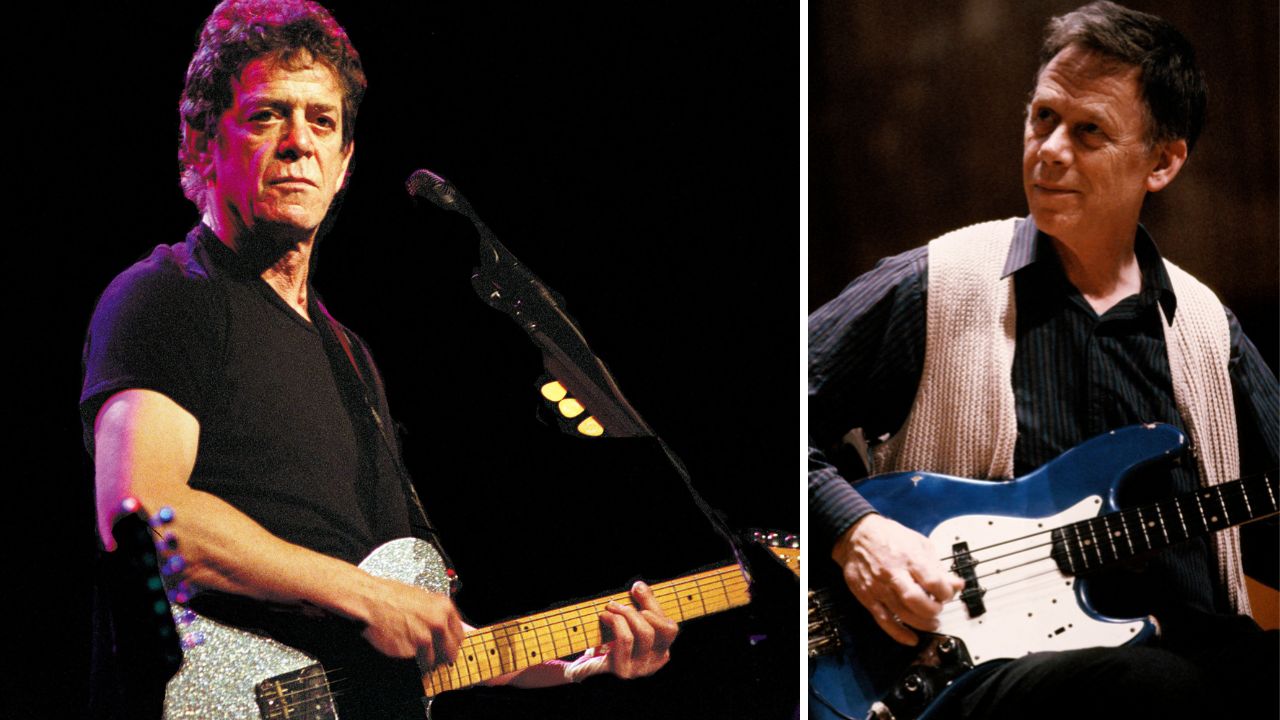

“I’m sick of people saying Walk On the Wild Side is a classic. I got paid £12, and David Bowie didn’t even show up”: Session bass legend Herbie Flowers on the making of Lou Reed’s 1972 hit – and the hardest session he ever did

Having recorded over 20,000 sessions for the likes of David Bowie, Dusty Springfield, T.Rex, Paul McCartney and Elton John, Brian ‘Herbie’ Flowers was not your average bassist

A former member of groups such as Blue Mink and Sky, the late Herbie Flowers toured with David Bowie and T. Rex, while his basslines, like the distinctive sliding line on Lou Reed's Walk On the Wild Side, are nothing short of legendary.

A veteran musician who started out playing the tuba and double bass in the Royal Air Force during the 1950s, Flowers recorded over 20,000 sessions, but, as he once told Bass Player, he wasn't always sure who the sessions were for.

“The rate was about £6 for a three-hour session, recording about 20 minutes of music. In those days, I spent more time with session drummer Barry Morgan than I did in bed with my wife! But you wouldn't necessarily know who it was for and the booker wouldn't give a shit who the band was.”

With two tracks simultaneously played on a bass guitar and a double bass, Flowers’ iconic bassline on Walk On the Wild Side is known the world over, adding a touch of class to one of the darkest pop songs ever written.

“I played that on my old English pine double bass and my Fender Jazz. There was no inspiration, just a bar of C and a bar of F going round and round. I'd put double bass on the bottom end, playing the bottom note, and then I asked to put bass guitar above because I wanted to try something else.

“But I'm sick of people saying, ‘Walk On The Wild Side is a classic, you must be rolling in it!’ I got paid £12, and Bowie – who was voted Producer of the Year – didn't even show up until all the tracks were down. That's good production, isn't it? Phone some clever people up, stay out of the way, then collect the award! It was just a lucky thing. I got paid £12 for the session, end of story.”

The following interview was first published in the October 2006 issue of Bass Player.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What are the golden rules for studio musicians?

“The first thing is that you can't ever be late. They play you the song or sling you a chord chart, and you come up with what you think are fancy basslines. You hang on to the click track, get your job done as quickly as you can, and as soon as they say, ‘Thanks very much’, get the hell out of there. Studio work is expensive. The producer doesn't want you hanging around, being in the way.”

Did you ever feel like you were in a band?

“A little bit. I was in T. Rex in the latter years, but T. Rex was Marc Bolan. Marc was the writer, performer, co-producer and publisher, and we were paid wages. It was all his, and I was perfectly comfortable with that.”

Did it bother you that you didn't own any part of a recording?

“I wouldn't want to own it. I don't want to own any part of Diamond Dogs or Transformer, because it could have been anybody. I had no involvement in the composition of Walk On The Wild Side, despite the fact that it's a pretty well-known bassline. It's only a bassline!”

What was the story behind Blue Mink?

“That began at Morgan Studios where six of us were booked for a two day session for a band called Family Dog. We finished in one day, so there was a day free. We decided to lay down some tracks as Roger Cook had this song called Melting Pot, and before we knew it, it was No. 2 in the charts. Two Little Boys by Rolf Harris stopped it getting to number one and I was playing on that too!”

And Sky?

“A hybrid band that sprang out of drummer Tristan Fry, Francis Monkman on keys and myself doing things for John Williams’ Travelling album. John was looking for another musical area so we put Sky together, made a few albums, did a few concerts, and were fortunate enough to get a hit with Toccata.

“Our diverse backgrounds gave us an advantage. We added Kevin Peek, who's really good at electric rock guitar. Francis was the original keyboard player with Curved Air and an early user of sequencers.”

What equipment did you take to sessions?

“If I was booked on bass guitar, I'd take my Jazz Bass and my little Wallace amp. The amp was only for my benefit as a monitor, and the engineer would say, ‘Can you turn your amp off for the take?’, so there’d be no spill. The speaker had wheels on it and if I played loud enough the speaker used to move across the floor! But we never played that loud in studios.

“I’ve also got a beautiful old English pine double bass that I bought in 1959 for £40, and an old tuba that I bought when I came out the Air Force for about £25. They're the only instruments I've ever had.”

Tell us about your Jazz Bass.

“I bought it in Manny's Music Store in New York, for $70 in 1959! To this day, it's got the same frets, pickups and dual pots, in Electric Blue sprayed over red, over the top of a white primer. I know because the paint's worn off the back.

“It's completely and utterly original, but it's never had a transfer on it, just the Fender 'F' on the bridge cover plate. I had to take the covers off because there was no room to play with a plectrum, but I've still got them in a drawer.”

So what else can you remember playing on?

“War Of The Worlds with Jeff Wayne, Brotherhood of Man, The Fortunes, every other Eurovision song, Love Affair, Sports Night and that Tony Hatch Crossroads theme, one of the hardest sessions I've ever done.

“A lot of the Pink Panther stuff, Dusty Springfield, Rock On by David Essex, a lot of the Nilsson Schmillson stuff. Elton John's early things, like Burn Down The Mission and Tumbleweed Connection. Eloise for the Ryan Brothers – that's got the longest bass gliss in the world.”

Nick Wells was the Editor of Bass Guitar magazine from 2009 to 2011, before making strides into the world of Artist Relations with Sheldon Dingwall and Dingwall Guitars. He's also the producer of bass-centric documentaries, Walking the Changes and Beneath the Bassline, as well as Production Manager and Artist Liaison for ScottsBassLessons. In his free time, you'll find him jumping around his bedroom to Kool & The Gang while hammering the life out of his P-Bass.

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

“One of the guys said, ‘Joni, there’s this weird bass player in Florida, you’d probably like him’”: How Joni Mitchell formed an unlikely partnership with Jaco Pastorius

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)