“Among vintage guitar collectors, a changed set of tuners can be a dealbreaker”: Guitar tuning pegs – everything you need to know about the parts that keep your guitar in tune

For guitar players, bassists and players of pretty much any stringed instrument, tuning pegs (also known as tuning keys, tuners or machineheads) are just a fact of life. Off the top of our heads, the only stringed instrument without tuners that we can think of is a tea-chest bass.

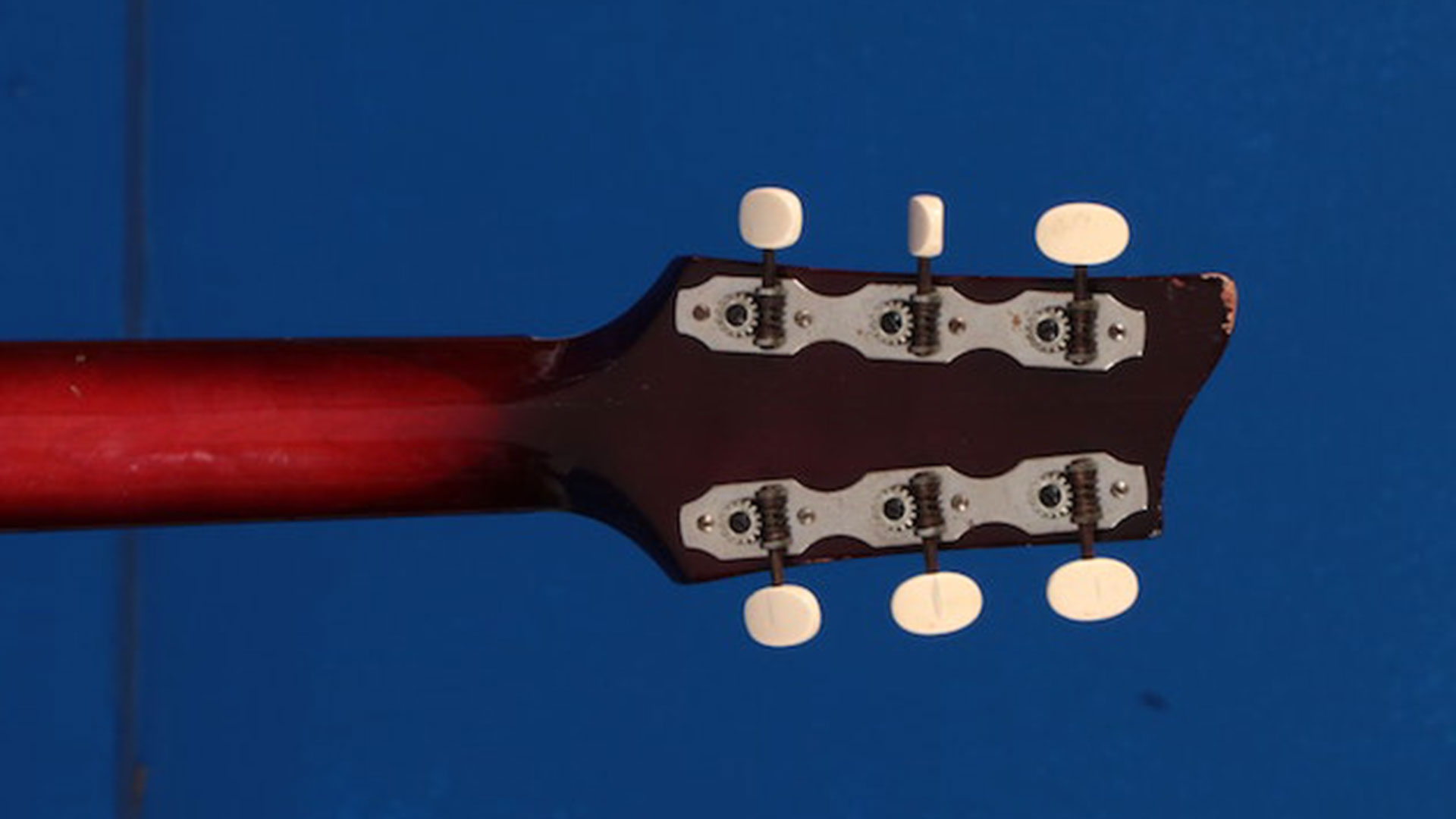

Some players express strong tuner preferences based on functionality, weight and appearance. Among vintage guitar collectors, a changed set of tuners can be a dealbreaker, Schallers on a vintage Gibson being a particular bête noire for some.

It’s pretty clear what tuners do. On instruments such as guitar and bass, the strings are stretched between two fixed points and the tuning peg sets the pitch of the open string by applying tension. Increasing this tension raises the pitch; decreasing it lowers the pitch.

Friction pegs are still used throughout the violin family and are one of the features that differentiate traditional flamenco guitars from ‘classical’ guitars. This is why some still use the archaic term ‘peg head’, rather than ‘headstock’.

The operating principle couldn’t be simpler. Carved from hardwoods, with a button or key at one end, each tapered peg is wedged into a hole in the headstock with a matching taper.

On guitars, the button end is located at the back of the headstock and the thin end protrudes through the front, with a hole drilled through it for attaching a string. Although it must be able to turn, a friction peg has to fit snugly into the headstock so that the friction resists string tension.

Friction pegs have a 1:1 ratio, which means that one complete turn of the key results in one string wrap around the peg. This rudimentary design makes accurate tuning very difficult, so some string players and flamenco guitarists are now using Wittner Finetune Pegs, with gears stealthily concealed inside the keys.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Gearing up

Steel strings present greater challenges for tuning accuracy and stability than gut or nylon strings, so you might think that geared mechanical tuners are a relatively recent development. But metal tuners actually originated in the mid-1700s and a viol and guitar maker called John Frederick Hintz has been credited with the first design.

Others mention an English guitar and cittern maker called John Preston, who designed a tuning system based on bolts and hooks that can still be seen on Portuguese Fado guitars.

Whether it’s a three-on‑a-plate set fitted to an 1800s Martin or a brand-new set on a PRS, they all operate in the same way

These designs were the precursors of the tuning pegs that we use today. Compared with earlier versions, the modern style of tuner is compact, elegant and efficient. But whether it’s a three-on‑a-plate set fitted to an 1800s Martin or a brand-new set on a PRS, they all operate in the same way.

The post of the tuner is the long section that has a string hole and it protrudes through the front of the headstock, and a pinion gear is attached to the bottom of the post. This meshes with a worm gear that is part of the shaft that the button is attached to.

The button makes it possible to turn the mechanism by hand, and a bushing on the headstock face keeps the post aligned and prevents it from leaning under string tension.

Tuners that are designed for classical guitars and slot-headed steel-string acoustic guitars are slightly different because the post holes are drilled through the sides of the headstock, rather than front to back.

The post for a tuner of this sort is flat all the way along, and since it presses into a blind hole on the inner side of the slot, there’s no need for a bushing.

Golden ratio

As we mentioned earlier, when a 360-degree turn of the tuner button results in a 360-degree post rotation, the tuner has a 1:1 ratio. The use of two gears in modern tuners means that designers can engineer various ratios for finer control. For instance, vintage Kluson tuners have a 12:1 ratio and require 12 button revolutions for each post revolution.

Some of the Kluson reissues now have a 14:1 ratio or even an 18:1 ratio. Ratios of 28:1 or even higher are available from other manufacturers, and Graph Tech’s Ratio set optimises the ratios for individual strings. These range from 12:1 to 39:1 with higher ratios used for the lower strings and lower ratios used for the plain strings.

While higher ratios facilitate precision tuning, the downside is that bringing new strings up to concert pitch takes longer. Investing in a button winder is advisable to speed up string changes.

Getting greasy

Over the decades, vast numbers of vintage guitars have had their original tuners removed and replaced. Often the tuners would have been worn out and players were obliged to use whatever replacements were available in the ’70s and ’80s.

But this usually meant widening post holes and adding screw holes. Perfectly viable tuners were often blamed for tuning instability issues that were more likely a result of badly slotted nuts and poorly maintained vibratos.

Older-style open-geared tuners sometimes stiffen up to the point where they’re barely usable. Without a cover to protect the workings, they are particularly vulnerable to dirt and dust, but they can often be refurbished. Once they’re removed from the guitar, try loosening the screw that secures the post gear and dismantle the tuner.

Soak the parts in naphtha for a few hours and then scrub them down with an old toothbrush to remove any debris. When reassembling the tuner, apply silicone grease wherever parts move against each other. But don’t use too much because it will create a mess and may end up soaking into the wood if it melts. Give the tuner several turns to work the grease in before fitting the tuners back onto the guitar.

With closed-back Kluson-style tuners, the process is similar. After leaving them to soak in naphtha, use a syringe to inject clean naphtha through the lubrication hole and flush out the housings. You’ll be amazed at the amount of dirt, old grease and metal particles that comes out.

Once the tuners have drained off and dried thoroughly, squirt a smallish amount of silicone grease onto the gears via the lubrication hole; work it into the mechanism and reinstall the tuners.

Die-cast tuners, as they are known, are intended to completely seal the gear mechanism and protect it from contaminants. They can be very long-lasting, but the grease may eventually solidify and adversely affect performance.

Most can be dismantled, cleaned and lubricated, and tutorial videos are easy to find online. If you discover that nylon washers have degraded or gone missing, you will need to source some replacements.

Attachment issues

Everybody has their own preferred method of securing strings to posts. Some do one wrap over the top of the hole and several beneath, while others just wrap below. Many tuner posts taper down towards the hole, which encourages the string wraps to bunch tightly together when tension is applied.

The infamous ‘luthier’s knot’ is said to guarantee stable tuning, but you may find it offers no improvement. Instead, it merely complicates string changes

The infamous ‘luthier’s knot’ is said to guarantee stable tuning, but you may find it offers no improvement. Instead, it merely complicates string changes while making it more likely you’ll poke holes in your fingers when you’re attempting to untie the knot.

The Kluson tuners that Fender used in the ’50s and ’60s had posts with a hole through the centre that were split at the top. This continued through the ’70s with the ‘F’ stamped tuners that Schaller manufactured for Fender. The string threads into the hole, is bent over to exit through the slot and then wraps around the post.

This design makes string changes quick and easy. You can also wrap the string around the post several times to optimise the break angle over the nut, which helps open strings to ring clearly when the headstock has no back angle.

The ‘locking tuner’ design that Sperzel introduced during the ’70s is almost as fast as Fender’s method and tightly secures strings. A thumbscrew located on the back of the gear housing opens and closes a clamp that’s built into the tuner post.

Simply thread the string through the post hole, pull it tight and lock the string in position. You may find the string only needs half a turn around the post before it reaches pitch.

Weighting for tone

Another rationale for replacing lightweight Kluson tuners on vintage guitars with die-cast tuners was the belief that adding mass to a headstock enhances sustain. Whatever you might think of the practice, it cannot be denied that most of the iconic ’Burst players used Grovers or Schallers. Then again, vintage Les Pauls tend to have otherworldly sustain irrespective of the tuners.

PRS’s Paul Reed Smith has expressed a preference for lighter tuners, arguing that heavy tuners dampen dynamics. This may explain why so many PRS guitars feature lightweight tuner buttons to lighten the load. The other downside of die-cast tuners is that there is a tendency towards neck heaviness – and therefore swapping to wood or plastic buttons may help.

High-quality vintage reissue tuners are readily available and many vintage guitar owners are now choosing to restore their guitars to original specs. Conversion bushings can be used to conceal oversized post holes, which means there’s no need to plug and redrill them.

Robot wars

Powered machineheads that automatically tune your guitar may sound appealing, and in recent years several companies have developed viable systems.

Jimmy Page endorsed the AxCent Tuning Systems and Trevor Wilkinson designed the ATD HT440. German company Tronical entered into an ill-fated deal with the tech-obsessed titans that formerly ran Gibson, but its Min‑ETune-equipped guitars failed to convince the guitar-playing public.

With accurate electronic tuning aids that can be clamped to headstocks, built into acoustic preamps or placed on pedalboards, surely there’s no need for robotic tuners? All you need are ears, eyes and fingers – long live the machinehead, we say.

The best tuning pegs – our recommendations

For Gibson-style guitars, our standout recommendation is the Schaller M6 135 Locking set. This set is renowned for its effortless installation process and unmatched durability, making them one of the most reliable locking tuners on the market.

Vintage aficionados may want to seek out the suitably retro Kluson Vintage Style Tulip 3L/3R N set. These '50s-style machine heads are not only great replacements for vintage parts, but they also maintain the same aesthetic and feel as the original.

Lastly, for Fender fans, we can't speak highly enough of the Fender Locking Tuners. Ideal for everything from Strats and Teles to Jags and Jazzmasters, these are a serious upgrade to vintage-style machine heads - and better yet, they won't break the bank.

Huw started out in recording studios, working as a sound engineer and producer for David Bowie, Primal Scream, Ian Dury, Fad Gadget, My Bloody Valentine, Cardinal Black and many others. His book, Recording Guitar & Bass, was published in 2002 and a freelance career in journalism soon followed. He has written reviews, interviews, workshop and technical articles for Guitarist, Guitar Magazine, Guitar Player, Acoustic Magazine, Guitar Buyer and Music Tech. He has also contributed to several books, including The Tube Amp Book by Aspen Pittman. Huw builds and maintains guitars and amplifiers for clients, and specializes in vintage restoration. He provides consultancy services for equipment manufacturers and can, occasionally, be lured back into the studio.

“It holds its own purely as a playable guitar. It’s really cool for the traveling musician – you can bring it on a flight and it fits beneath the seat”: Why Steve Stevens put his name to a foldable guitar

“Finely tuned instruments with effortless playability and one of the best vibratos there is”: PRS Standard 24 Satin and S2 Standard 24 Satin review