The 50 greatest guitar riffs of all time

From metal to rock, punk to grunge, these are the best guitar riffs ever recorded, as voted for by you

10. Purple Haze – The Jimi Hendrix Experience (1967)

Hendrix adds a new chord to the lexicon

Before Purple Haze, E7#9 was strictly a jazz chord. Only a visionary would consider using it as the tonal centre; conventionally, it was considered too dissonant for mainstream listeners. The Hendrix chord is a cliché now, but then it was a revolution.

Hendrix’s fearless embrace of dissonance opens the song, with bass and guitar stamping out the devil’s interval. The intro sees Jimi finding exciting new lines in the well-worn framework of the minor pentatonic. Then comes that chord.

His strumming is impossibly funky and the fuzz obscures exactly what he’s doing, so almost no-one has replicated it. By using his thumb to play the root notes of the G and A barres, he leaves his finger free to add the major 6th to those chords.

The gear? Definitely Marshall and Fuzz Face, but there’s a persistent legend that Jimi had knackered his only Strat and had to borrow Noel Redding’s Telecaster.

9. La Grange – ZZ Top (1973)

The little finger is the key, says Billy G…

The Texan trio’s hit album Tres Hombres featured this perennial tune. La Grange was inspired by Edna’s Fashionable Ranch Boarding House, a brothel on the outskirts of that titular Texas town. For the suitably lowdown ’n’ dirty riff, Billy Gibbons took a hoary, John Lee Hooker-style I-bIII-IV vamp in A (A-C-D), and poured his trademark tone all over it.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“That’s a 1955 Fender Strat,” Gibbons tells TG, “maple neck with a hardtail [fixed bridge], running through a 2x10 Fender Tremolux – a little blonde piggyback amp that happened to be in the studio at the time. The riff’s in the key of A, but don’t forget to use the little finger on the G string [C note, 5th fret] and pull it slightly up to pitch.”

Bend that up just shy of C# to get yourself some of the song’s bluesy, raunchy feel...

8. Walk – Pantera (1992)

The riff that ushered in a bold new era for metal

Pantera were soundchecking on the Cowboys From Hell tour when guitarist Dimebag Darrell started playing what would soon become the most definitive track of their career. His brother Vinnie Paul quickly joined in on drums, later recalling how it had a shuffle rhythm unlike anything they’d written up to that point and nodded back to the siblings’ Southern roots, growing up around the music of ZZ Top and Lynyrd Skynyrd 50 kilometres south of Dallas.

Walk was ultimately less thrashy and saw the band embracing more groove-driven doctrines of heaviness – inspiring a whole new wave of sonic aggression. The riff, as simple as it sounds, could easily be one of metal’s most misconstrued, often incorrectly tabbed without those crucial first fret bends. And though it doesn’t sound hugely wrong when played ‘straight’, there’s a certain magic to how Dimebag wrote it – the slurred increases and decreases in pitch giving the music an almost rubbery and mechanical kind of feel.

The descending diads that get thrown in as the idea evolves bring further discordance, rooted around harsher-sounding intervals like the minor sixth and tritone, before concluding with some faster palm-muted chugging on the lower frets.

At this stage in his career, the guitarist was mainly playing his 1981 Dean ML, instantly recognisable for its lightning bolt paint job and Kiss stickers on the upper fin, and equipped with a high-output Bill Lawrence L 500 XL pickup in the bridge.

Dubbed the ‘Dean From Hell’, he’d actually won the instrument in a guitar contest as a 16 year-old before selling it “to raise money for some wheels” and was later gifted the same ML back, customised with a new custom paint job, Floyd Rose tremolo system and ceramic bridge pickup. The instrument can be seen in the Walk video, as well as a brown tobacco-burst ML that was also in the studio for the Vulgar Display Of Power sessions.

In place of the Randall RG100H heard on Cowboys From Hell, and brought back later on 1996’s The Great Southern Trendkill, Dimebag was plugged into a Randall Century 200 head – again achieving his own signature sound by cranking the gain and scooping the mids on a solid-state amp, rather than anything valve-driven. Solid-state felt more in your face, he once reasoned, noting how his Randalls had no shortage of warmth but also “the chunk and the fuckin’ grind”.

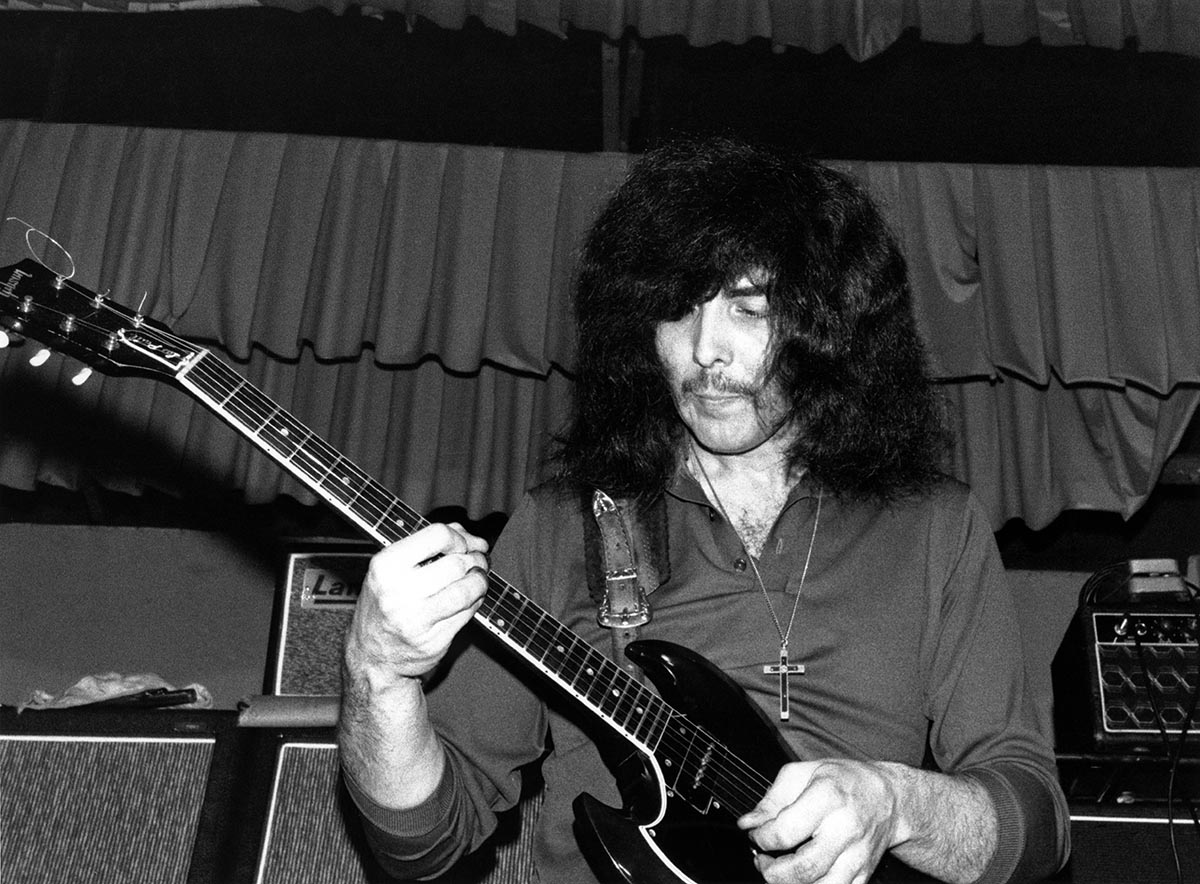

7. Iron Man – Black Sabbath (1970)

The biggest hook in a legacy littered with them

Tony Iommi’s influence on heavy metal and rock in general is one that cannot be overstated. Most players would be proud to have written just one classic riff – the left-handed Black Sabbath six-stringer has penned countless, sometimes several within the same song.

Indeed, Iron Man has a few of its own to offer, though it’s the slow doomy blues of its main riff that singlehandedly delivers on their themes of armageddon and revenge, narrating the plight of a time-travelling robot man forsaken by those he’s trying to help.

Iommi has often spoken of how his most famous ideas came to him in the moment and on the spot – this American single from Sabbath's second album Paranoid being no different. “I was in a rehearsal room, and Bill started playing this boom, boom, boom,” Iommi recently revealed, noting how “in my head I could hear it as a monster” or “someone creeping up on you”.

The opening drones were played using a behind the nut bends on the open low E, giving his guitar a machine-like growl as Ozzy announces the immortal words ‘I am Iron Man’ from behind a metal fan.

The main riff is in B minor, using powerchords that follow up the pentatonic scale before more dissonant-sounding slides from the minor 6th to the 5th – all fretted on the thicker strings for a fuller sound and further intensified by drummer Bill Ward’s snare hits. It’s this juxtaposition, the lethargic opening segment against its busier second half, that demonstrates Sabbath at their most memorable, mutating familiar bluesy roots into something darker and doomier.

Like most tracks on Paranoid, it was performed on Iommi’s left-handed ‘Monkey’ 1965 Gibson SG Special, which was swapped for the right-handed SG Special heard on Sabbath’s debut – the backup guitar that served him well after his Strat gave in. Just before recording album number two in June 1970, now armed with a guitar he didn’t have to play upside-down, Iommi went to see luthier John Birch for some upgrades, including a new P90-style Simplux neck pickup and a rewound bridge pickup for more power.

The signal then went through a modded Dallas Rangemaster treble-booster and into his single-channel Laney LA 100 BL head and matching cabinet. When TG interviewed the Black Sabbath hero in 2010, he explained how the pedal was engaged to “give my sound a bit more oomph” and push the signal going into his Laney, thus attaining the kind of “overdrive I was looking for, which amps in the early days didn’t have”.

6. Enter Sandman – Metallica (1991)

A watershed moment for heavy metal history

Some years are watershed moments in musical history, and 1991 was one of them. It was the year grunge broke and hair metal was given a shove out of the mainstream. It was also the year that Metallica’s self-titled fifth album was released. Forever known as ‘The Black Album’, it was the record that established the San Francisco quartet as the biggest metal band in the world.

And while it yielded five hit singles – Nothing Else Matters, The Unforgiven, Sad But True, Wherever I May Roam and Enter Sandman – it was the latter that really caught the public’s imagination, reaching No 5 in the UK chart.

With its doomy, clean-picked minor key riff, haunting lyrics and massive sound, it was the track that set the template for the rest of The Black Album, both in sound and in atmosphere. It was also the first song written for the album, born from a riff lead guitarist Kirk Hammett brought in.

But as drummer Lars Ulrich explained in a Classic Albums documentary: “The riff that’s on the record and the way it exists today is not really the way Kirk wrote it.” Hammett’s initial idea was the first five-note refrain morphing straight into the powerchord breakdown. But by chopping and repeating the first clean riff, and doubling it up on the bass, Enter Sandman as we know it was born.

“We tried to expand every sound to the max,” said producer Bob Rock. “We tried to get the guitars as big as possible, the bass as big as possible, the drums... You know, big and weighty.”

To this end, Rock insisted on the band playing together in one room, contrary to their previous M.O. “They thought it was a lot of work,” Rock told Mix magazine, “and they didn’t understand it. But this was the only way I knew how to make a record. To me, it was about capturing the feel that they wanted.”

Both Hetfield and Hammett are ESP men, and for The Black Album sessions Kirk played through Marshall amps with Mesa/Boogie heads. However, the amp that Hetfield ran his black ESP Explorer through was a little more complex, as engineer Randy Staub told Mix.

“We ended up building this huge guitar cabinet for him,” Staub said. “I think we had nine or 11 cabinets – some stacked on top of each other, some on the floor – and then we’d get this huge tent around this pile of cabinets curtained because as we were getting James’s guitar sound, he kept saying, ‘I want it to have more crunch!’”

They got the crunch, the weight, the heaviness. Ultimately, they got the defining metal song of the '90s.

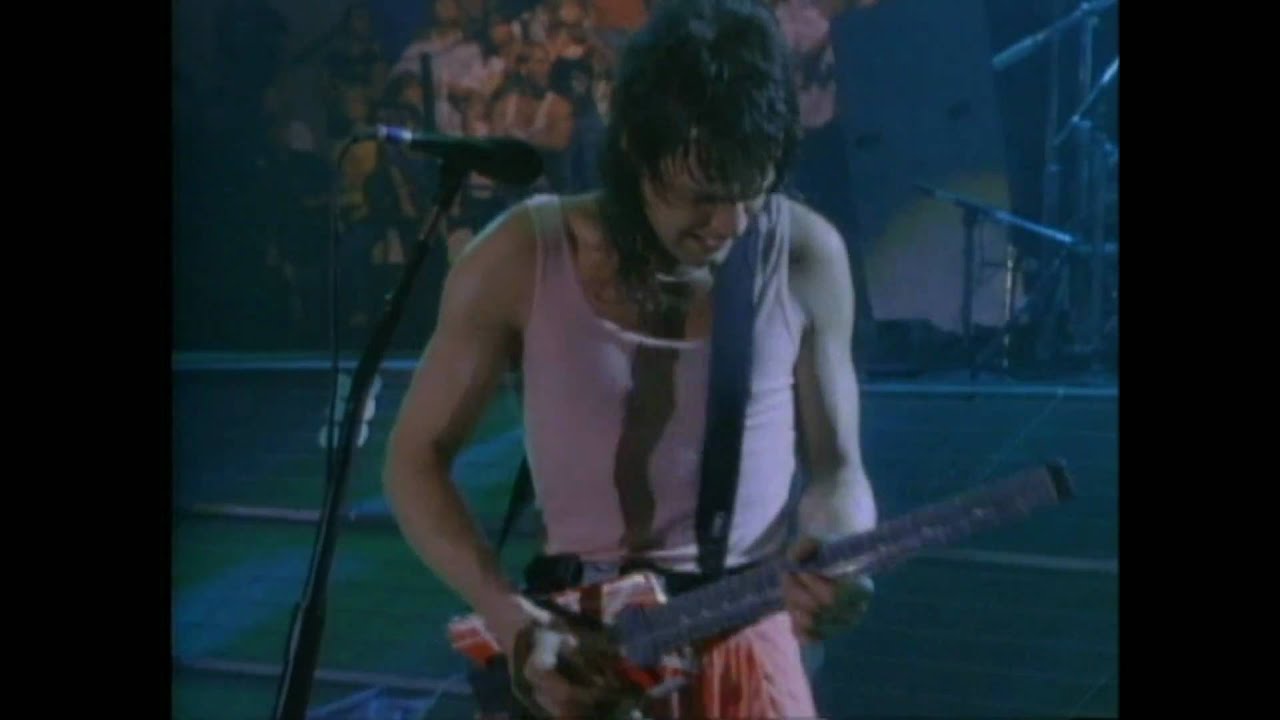

5. Ain't Talkin' 'Bout Love – Van Halen (1978)

How to turn a basic exercise into a world-conquering anthem

Proving that arpeggio homework can pay off rather handsomely, this early Van Halen track was built around a simple A minor shape, played palm-muted half a step down, and ended up becoming one of their most famous recordings.

On the game-changing debut, EVH was using his self-made Frankenstrat, built out of factory reject parts, then fitted with a 1958 Stat tremolo system and a Gibson ES-335 PAF pickup in the bridge. The swirling effect came courtesy of his MXR Phase 90 before the signal was fed into the late-'60s Marshall 1959 Super Lead that was used on all the David Lee Roth-era albums.

4. Smoke on the Water – Deep Purple (1972)

The rock classic that almost didn’t exist

It has one of the most recognisable and oft-played riffs in rock ’n’ roll history – solid, simple and catchy as hell. It’s no surprise to see this track at the sharp end of our poll! And yet, as Deep Purple singer Ian Gillan told TG, Smoke On The Water might never have been released, because initially the band didn’t think of it as anything special.

In the winter of 1971, when Purple began work on the Machine Head album in Montreux, Switzerland, guitarist Ritchie Blackmore played the riff in their first jam session, and as Gillan recalled: “We didn’t make a big deal out of it. It was just another riff. We didn’t work on the arrangement – it was a jam.”

But by the end of the recording sessions they came up short of material, and so, in Gillan’s words, “We dug out that jam and put vocals to it.” Blackmore played his Strat and was plugged into – as far as Gillan could recall – “a Vox AC30 and/or a Marshall”. Over that mighty riff, the singer told the true story of how the Montreux casino – where Purple had been scheduled to record – burned down in a fire that started during a Frank Zappa concert. And with that, a deathless rock classic was created.

3. Back In Black – AC/DC

The biggest riff from rock's biggest album

Malcolm Young had it all planned out from the very start. When the rhythm guitarist formed AC/DC in 1973 with his kid brother Angus on lead, he knew exactly how to make the band’s sound as powerful as possible.

As Angus recalled: “Malcolm’s idea was that two of us were always a unit together. We worked as that one unit and tried to make it one big guitar.” And there is no better illustration of this than Back In Black – the title track from what became the biggest-selling rock album of all time.

It was an album born out of tragedy, following the death of AC/DC’s singer Bon Scott in February 1980. But with a new singer, Brian Johnson, the band pulled off the greatest comeback ever seen in rock ’n’ roll. And for an album that Angus described as “our tribute to Bon”, the title track was hugely symbolic. That funky, earth-shaking riff was one that Angus had first started toying with back in 1979 during the Highway To Hell tour, Bon’s last with the band.

The album was recorded in just six weeks with producer Mutt Lange, who had cut Highway To Hell and would go on to make Def Leppard’s monster hit Hysteria. Lange’s right-hand man, engineer Tony Platt, described the recording process to Premier Guitar.

“There was a definite focus to record Back In Black as basically and as live as possible,” Platt said. “So all the songs were tracked with Angus and Malcolm, bass and drums. On a few occasions we may have dropped in a chord or so on a great take.”

Angus Young has always favoured a Gibson SG (leaving the standard issue pickups in it), and has always recorded with it. The Back In Black sessions were no different. His amps were Marshalls as usual.

“Still 100-watt Super Leads,” Angus told Guitar World. “The old-style ones, without those preamp things. I remember at the time that was the new thing Marshall was trying to push. They were trying to get people interested in ’em, but I wasn’t really interested.”

As Malcolm recalled it: “I think Angus went to a smaller 50-watt Marshall for his solos. Just for some extra warmth. I was still using my Marshall bass head...”

A lot of people who have picked up my guitar and tried it through my amp have been shocked at how clean it is. They think it’s a very small sound when they play it and wonder how it sounds so much bigger when I’m playing

Angus Young

Despite Angus’s massively crunchy guitar tone, he seldom cranked up the overdrive. “The amp is set very clean,” he said. “A lot of people who have picked up my guitar and tried it through my amp have been shocked at how clean it is. They think it’s a very small sound when they play it and wonder how it sounds so much bigger when I’m playing. I just like enough gain so that it will still cut when you hit a lead lick without getting that sort of false Tonebender-type sound. I like to get a natural sustain from the guitar and amp.”

What AC/DC created in Back In Black was, according to Def Leppard guitarist Phil Collen, “the ultimate rock song”. As Phil said: “It has that sexy groove that hardly any rock band could get close to, amazingly restrained, confident guitars that are pure rock, outrageous drums and a vocal meter that is almost a rap but very rock ’n’ roll. And considering the song is based on a blues format, it’s extremely original.”

2. Crazy Train – Ozzy Osbourne (1980)

How Randy Rhoads resurrected a lost soul

When he was kicked out of Black Sabbath in 1979, Ozzy Osbourne feared that his days as a rockstar were over. Until, that is, a young American guitarist named Randy Rhoads came into his life. Rhoads, poached from LA band Quiet Riot, would prove the perfect foil for Ozzy’s reinvention post-Sabbath.

On his debut solo album Blizzard Of Ozz, that unique voice was framed in a modern context, in which Rhoads’ ferocious neo-classical guitar technique was pivotal. And Crazy Train was the key track – an anthem that would forever define Ozzy as a solo artist and Randy as one of the great guitarists of his generation.

Unusually, the Crazy Train lick was not in the standard metal keys of A or E, marking the first time a guitarist had written to order for Ozzy’s doomy holler. “In Sabbath,” he noted, “they’d just write something and say, ‘Put a vocal on that.’ Randy was the first guy to make it comfortable for me.”

Years later, questions would be raised over the authorship of the Crazy Train riff. Greg Leon, who played bass alongside Rhoads in Quiet Riot, claimed: “I showed Randy the riff to Steve Miller’s Swingtown. I said: ‘Look what happens when you speed this riff up.’ We messed around, and the next thing I know he took it to a whole other level.” But this was disputed by Bob Daisley, bassist on Blizzard Of Ozz.

“The signature riff in F# minor from Crazy Train was Randy’s,” Daisley said. “Then I wrote the part for him to solo over, and Ozzy had the vocal melody. The title came because Randy had an effect that was making a psychedelic chugging sound through his amp. Randy and I were train buffs, and I said: ‘That sounds like a crazy train.’ Ozzy had this saying, ‘You’re off the rails!’, so I used that in the lyrics.”

Released as a single in 1980, Crazy Train was only a minor hit (peaking at No.49 in the UK). But the song’s influence on the guitar scene was inestimable.

“I remember the moment I first heard Randy,” said Rage Against The Machine guitarist Tom Morello. “I was packed in the back of somebody’s mom’s hatchback in Libertyville, and Crazy Train came on. This blistering riff came at me, followed by an incredible solo, and of course there was Ozzy – I recognised his voice as the guy from Black Sabbath. By the end I was like: ‘What just happened?’”

Crazy Train set Ozzy on the path to mega-stardom, and confirmed Randy Rhoads as the most gifted guitar player to emerge since Eddie Van Halen. Tragically, he would not live to fulfil his potential. He died in a plane crash in 1982, after recording one more album with Ozzy, Diary Of A Madman. But his influence was profound, and as Tom Morello said in tribute: “Randy was the greatest hard rock guitar player of all time.”

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences as a guitar player. He's worked for magazines like Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Prog, Record Collector, Planet Rock, Rhythm and Bass Player, as well as newspapers like Metro and The Independent, interviewing everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handled lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).

![Pantera - Walk (Official Music Video) [4K] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/AkFqg5wAuFk/maxresdefault.jpg)

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)