The greatest guitar albums of the ‘70s: Getting the Led out with Sabbath, the Who, Pink Floyd and more

Punk was a revolution, disco a global phenomenon, but the guitar music of the '70s was dominated by the giants of rock. Here are the decade's top 10 guitar albums, as chosen by you...

- 10. Black Sabbath – Paranoid (1970)

- 9. Pink Floyd – The Wall (1979)

- 8. Boston – Boston (1976)

- 7. AC/DC – Highway To Hell (1979)

- 6. Pink Floyd – Wish You Were Here (1975)

- 5. Deep Purple – Machine Head (1972)

- 4. Led Zeppelin – Physical Graffiti (1975)

- 3. Pink Floyd – The Dark Side Of The Moon (1973)

- 2. Van Halen – Van Halen (1978)

- 1. Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin IV

In the second installment in Total Guitar's Greatest Guitar Albums of All Time, we're going to be looking at an era when the big beasts of rock turned up the volume, went big and bold with ideas that changed guitar music for keeps.

If the greatest guitar albums of the ‘60s revolutionized rock 'n' roll, deflowering it amid the political turmoil of the decade, the '70s conducted rock on a scale like never before.

After you voted in your thousands, we bring you profiles of your top 10 albums, and offer an in-depth look at the decade's number one album.

10. Black Sabbath – Paranoid (1970)

The definitive choice for guitarists who recognize that rhythm parts are more important than solos, Sabbath’s second album, Paranoid, saw riff lord Tony Iommi laying down the metal blueprint.

Iron Man, War Pigs and the title track are the foundation of heavy metal, with Iommi sounding crushing even before the band discovered downtuning. The solos are fluid and exciting, usually improvised as part of live takes with the band; Iommi would add rhythm parts underneath later. But the riffs are the real story.

Pete Townshend was known for power chords, but his sledgehammer strumming did sometimes include the major third. It was Iommi who really codified the root and fifth power chord we all play today.

Iommi liked the amps he got free from local manufacturers Laney, but he was always pushing for more gain. On Paranoid he was using a modified Rangemaster treble booster to overload the amp input.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

To keep the low frequencies tight, Iommi ran the guitar amp’s bass control on 0 while maxing every other control. His Gibson SG’s humbuckers helped too, with more push than the Strat he’d had in Sabbath’s early days. The title track, though, was played on a Les Paul, the only time Iommi recorded with one.

9. Pink Floyd – The Wall (1979)

By the time Floyd recorded this sprawling double album, David Gilmour’s Black Strat had a Charvel maple neck and a high output DiMarzio FS-1 bridge pickup, although other guitars delivered some of The Wall’s most famous moments.

The Nile Rodgers-ish main riff on Another Brick In The Wall (Part 2) was played on a 1954 Fender Stratocaster, serial no 0001, and the solo came from a 1955 Les Paul Goldtop with P90 pickups and a wraparound tailpiece.

But the Black Strat delivered the Comfortably Numb solo, through the Big Muff Pi pedal Gilmour first used on 1977 album Animals. Gilmour’s enormous live tone came from splitting his pedalboard signal and feeding each output through a separate Boss CE-2 chorus pedal.

8. Boston – Boston (1976)

Spearheaded by the classic hit single More Than a Feeling, Boston’s debut would go on to sell 17 million copies in the US alone. While Van Halen’s debut set the standard for guitar playing in the 80s, Boston’s heavily multi-tracked, chorused guitars and glossy production were just as influential on the overall sound of the coming decade.

Bandleader Tom Scholz, an MIT graduate, was equal parts mad scientist and guitarist

Bandleader Tom Scholz, an MIT graduate, was equal parts mad scientist and guitarist. Building a studio in his spare time, the perfectionist designed new equipment to produce the sounds in his head.

When Boston’s debut hit big, Scholz commercially released his inventions the Rockman Headphone Preamp and the Power Soak, a pioneering attenuator for valve amps. The Rockman appeared on albums by Def Leppard, Joe Satriani, and David Gilmour.

Boston’s heavily compressed clean tones and harmonized distorted guitars immediately defined the sound of AOR radio, and still sound amazing today.

The guitar parts are complex interweaved layers of rhythm and lead lines with different tones, making Boston a stepping stone between Queen albums and the even more complex productions that producers like Trevor Horn and Mutt Lange would create in the 80s. Scholz’s Les Paul produced a high gain tone that didn’t offend anyone, making it the ideal power ballad sound.

7. AC/DC – Highway To Hell (1979)

Producer Mutt Lange polished the sound enough to push AC/DC in to the big league with Highway To Hell, while leaving enough rough edges that no diehard fans were alienated.

Rhythm guitarist Malcolm Young stuck with his modified Marshall Superbass, while lead guitarist Angus Young – according to Solodallas founder and AC/DC obsessive Filippo Olivieri – used a Marshall 2203.

Lange tamed Angus’s shredding, producing his most melodic and considered solos to date. And on an unparalleled set of riffs, Malcolm’s almost-clean Gretsch and Angus’s slightly dirtier SG remains the best sounding guitar pairing in history. Their telepathic timing and epic open powerchords are the definition of rock guitar.

6. Pink Floyd – Wish You Were Here (1975)

David Gilmour’s titanic playing on Shine On You Crazy Diamond has some of the most imitated feel and tone in history. Gilmour pays tribute to blues pioneers, particularly BB King, with his controlled feel and sublime behind-the-beat timing.

The Black Strat was still largely stock in 1975, and throughout this album his Colorsound Powerboost is featured – largely into his Hiwatt DR103. A silicon Fuzz Face lifts his slide parts, and an MXR Phase 90 appears for the first time.

Back in the real world, you can get close to Gilmour’s sustaining, cleanish tone with a compressor and a low-gain overdrive pedal like a Boss Blues Driver.

5. Deep Purple – Machine Head (1972)

Deep Purple’s sixth studio album is, of course, much more than just that riff, but Machine Head deserves to be in this list for Smoke On The Water alone.

Guitarist Ritchie Blackmore said simplicity was the key to the song’s success, but playing it like him is surprisingly tricky. Blackmore originally used pick and fingers to play both notes in each double stop at the same time.

The solos in Lazy and Pictures Of Home raised the bar for technique and expression

Hendrix had exploited the potential of a Strat and a Marshall on 10, but Blackmore found a whole different set of sounds in that combination. There was no trace of icepick treble in his gutsy tone.

His unforgettable riffs and fluid soloing drew on both classical and blues influences to broaden the vocabulary of rock guitar. Even the self-critical Blackmore had to admit there were good bits on Machine Head.

Highway Star was his homage to Bach, and his alternate picking was cutting edge for the time. He insisted it was the only solo he wrote before recording. Elsewhere, his off-the-cuff soloing exhibited feel, control, and his unmistakable approach to the tremolo arm. The solos in Lazy and Pictures Of Home raised the bar for technique and expression.

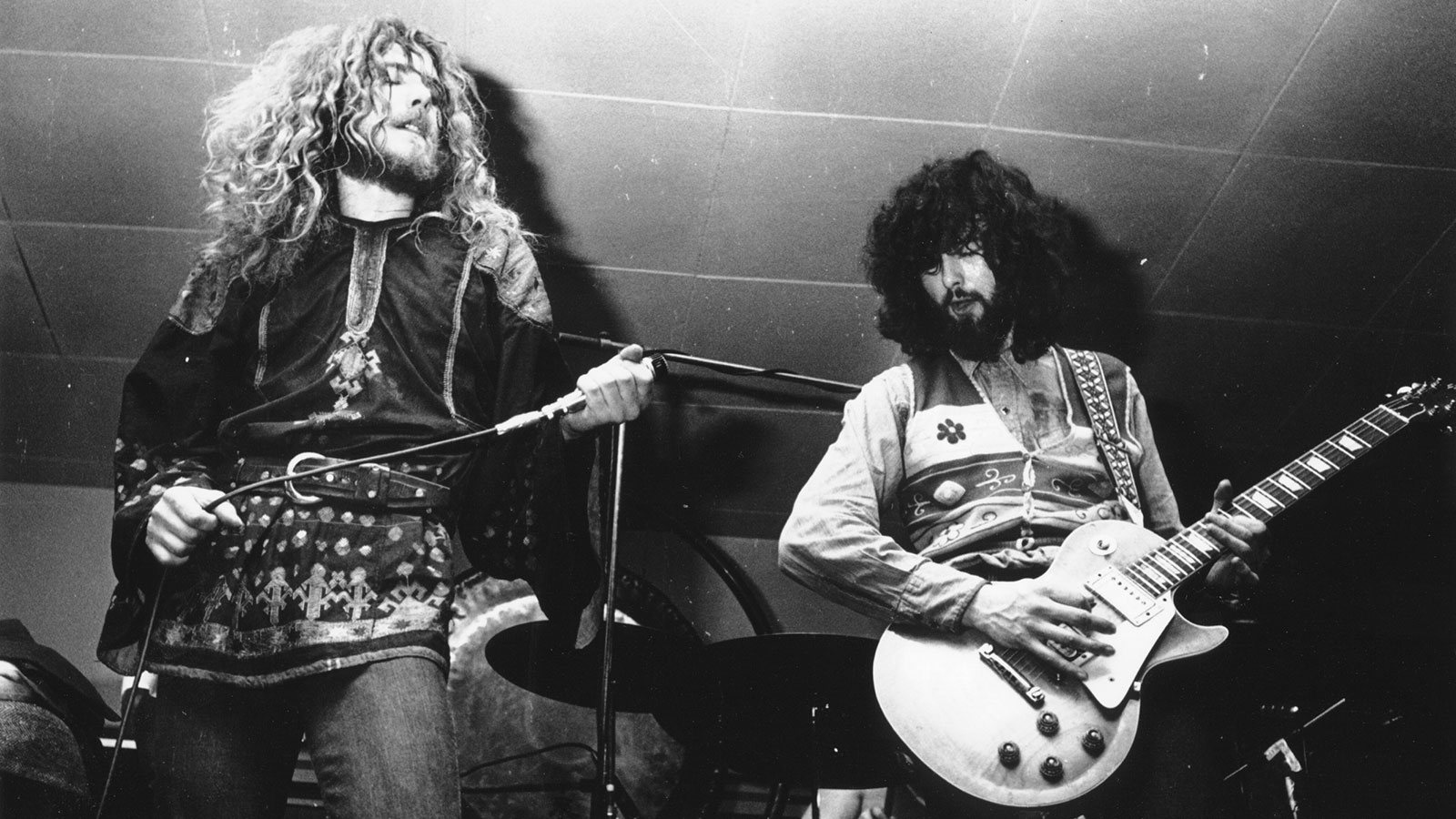

4. Led Zeppelin – Physical Graffiti (1975)

After the polished Houses Of The Holy, Zeppelin threw everything at Physical Graffiti, their philosophy of ‘tight but loose’ at the fore. Kashmir and Ten Years Gone have their sharpest arrangements, while In My Time Of Dying was essentially a jam.

The song lasted over 11 minutes partly because they hadn’t rehearsed a proper ending. The double album format let Zeppelin demonstrate everything they could do, from thundering hard rock to acoustic folk. Jimmy Page’s Danelectro emerged for Kashmir, while his Martin D-28 never sounded better than in Bron-Yr-Aur.

3. Pink Floyd – The Dark Side Of The Moon (1973)

Floyd’s most famous album was also The Black Strat’s finest hour, as David Gilmour laid down some of the tastiest solos of the decade. While Ritchie Blackmore set new standards for flash, Gilmour’s tasteful phrasing and sublime behind-the-beat feel showed the power of a few well-placed notes.

The Black Strat was still in close-to-stock form at this point, with its original pickups and white pickguard. His glorious fuzz tone, a silicon Fuzz Face boosted by a Colorsound Powerboost overdrive, is one of the most sought-after sounds in rock. His custom Bill Lewis axe also crops up; Gilmour makes use of its full 24-fret range towards the end of Money.

2. Van Halen – Van Halen (1978)

The date on the sleeve says 1978, but a cursory listen to Van Halen’s debut tells you that it is, by some distance, the greatest guitar album of the 1980s. Van Halen didn’t have much in common with The Clash or the Sex Pistols, but the Californians’ brand of ‘Atomic Punk’ had the same urgency as the London punks.

None of Van Halen’s 11 tracks gets near the four minute mark, the perfect antidote to sprawling 70s excess. MTV was three years away, but Van Halen had already invented MTV rock. “We’re playing the 80s,” grinned effervescent frontman David Lee Roth. “Other bands are still playing the 70s.”

We’re playing the '80s. Other bands are still playing the '70s

David Lee Roth

The songs zipped by so quickly partly because Eddie could play his borrowed Clapton licks at four times their original speed. But describing EVH’s guitar playing as “fast” undervalues it, like describing the Great Pyramid of Giza as “large”.

Not just the best soloist on the planet, Eddie was possibly even better at rhythm – effortlessly grooving, extremely dynamic, and with the best swing in the game. Debates about whether he invented tapping (answer: no) are beside the point.

Eddie Van Halen also did not invent harmonics, divebombs, palm muting, legato, or high gain tones, but no one had combined them seamlessly into one coherent guitar style, let alone perfected it on their debut album.

Many of the final tracks are first takes, and it never sounds like Eddie might screw up. Where he hits a wrong note, he styles it out and keeps on wailing. Like the gymnast Simone Biles, no matter what acrobatics happen in the air, he always sticks the landing.

Besides his cutting edge technique, Eddie was best known for his infectious grin. Asked about Van Halen in 1986, Jimmy Page remarked, “It’s an incredible technique for what he does. I can’t do it. I can’t smile like him either.”

Eddie’s smile reflects the sheer exuberance bursting from the grooves on the first Van Halen album. Listening to it is a joyful experience, and that love of music gave meaning to every note they played. Eddie’s licks had soul, even when he was showing off.

Then there was the tone. It’s doubtful the electric guitar has ever sounded better. Guitarists have devoted their lives to trying to discover how it was done.

John Suhr worked on Eddie’s Marshall Plexi in 1991 and swears blind there was nothing unusual about it. He posted on The Gear Page forum in 2010, “When Ed played through this amp in my shop, it sounded every bit like Ed and the first album. When I played through it, it sounded every bit like me. Ed would make any decent amp sound like Ed.”

The 23-year-old Eddie didn’t just invent 80s rock guitar; he did it in a way that no one would ever surpass. A generation of shredders took his technique to new heights, but no one had the tone or the vibe, and no one else looked like they were having nearly as much fun.

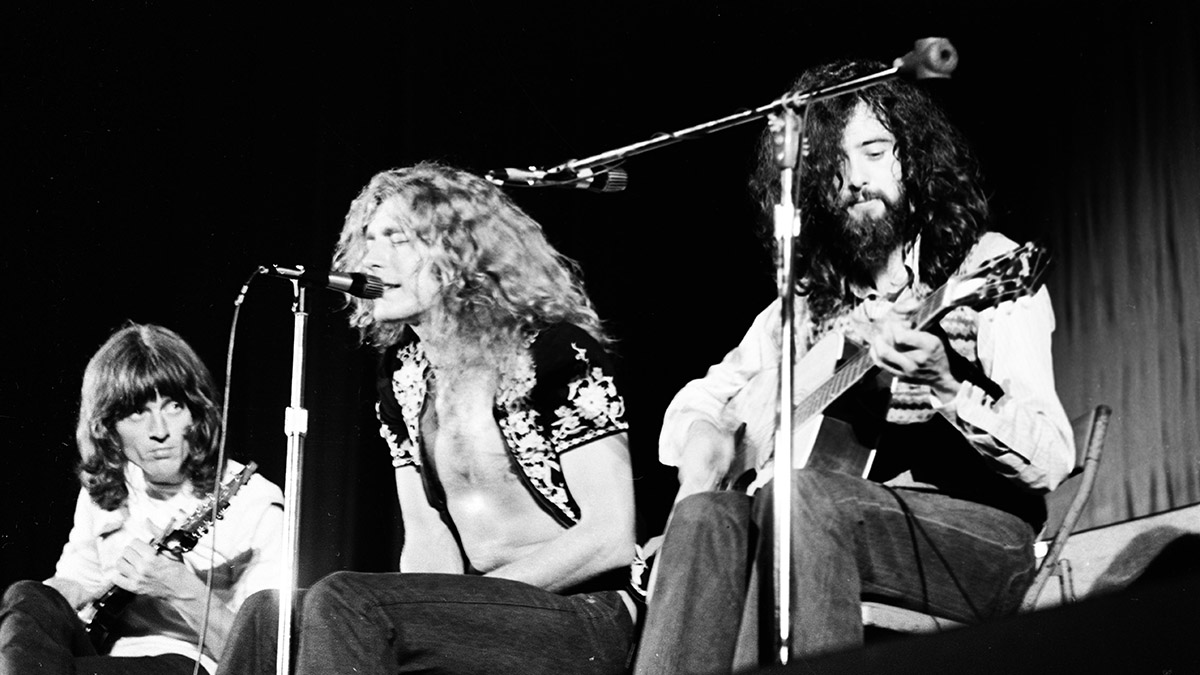

1. Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin IV

Led Zeppelin III was hardly a flop, but Jimmy Page took criticism of it personally. The guitarist refused interviews for the next 18 months and resolved to let the music do the talking in the most dramatic way possible.

The next album would have no accompanying words – not even the band’s name on the cover. The resulting untitled effort, known universally as Led Zeppelin IV, is the most devastating answer a band has ever given their critics.

I liked the idea of everybody being in the same house and really working with the whole band

Jimmy Page

“It was a really good and serious summing up of where we were,” said Jimmy Page of the album. “Each song has its own character. It gives all the different colors and textures of the band. We were moving the acoustic aspect of what we’d done on the third album into these more intimate areas with Going To California and The Battle Of Evermore. The music kept expanding.”

It was in 1970 that Page, singer Robert Plant, drummer John Bonham and bassist John Paul Jones began the first recording sessions for the album at Island Studios in London, but the magic was not happening. According to Page, an early version of a key track, When The Levee Breaks, sounded “labored”. The guitarist decided a new working environment was required.

He wanted somewhere the band could live, write, and record, so Led Zeppelin retreated to Headley Grange, a disused workhouse for the poor in Hampshire. Renting the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio to capture the results, the band dug in.

“I liked the idea of everybody being in the same house and really working with the whole band,” Page recalled. “It was an old Victorian house, very imposing. It was in the countryside, so you weren’t going to have neighbors complaining. If it didn’t work we’d go into a studio, but in actual fact it was great. It was like everybody’s creative energies all joined. That’s what the whole magic of the environment was like.”

The band used cupboards and stairwells around the house as isolation booths for amps, setting up temporary studios ad hoc. They were constantly setting up in different locations, lending each track its own ambience.

As Page said, “We used the acoustics of the house. We were playing in this drawing room to begin with, and then John Bonham has another drum kit turn up, and it’s in the hall, with this really high ceiling. When he started playing it was like, ‘right, we’ll have to do something in here now,’ with the drum sound like that, because it was just huge. You’ve heard it – on When The Levee Breaks.”

Levee was Zeppelin’s thunderous reimagining of a 1929 Memphis Minnie tune. Although the melody does draw on the original, it’s unlikely anyone would have recognized the song if Plant had bothered to change the lyrics. Memphis Minnie’s tune was an up-tempo blues with a bright fingerpicking part.

The original follows standard 12-bar chord changes, but Page’s ominous, droning riff never modulates, designed to invoke a trance. He played it on his Fender Electric XII in Open G tuning, but it sounds like Open F because Page slowed the track with varispeed.

“If you slow things down, it makes everything sound so much thicker,” he told author Brad emphasized. “The only problem is, you have to be very tight with your playing because it magnifies any inconsistencies.”

Working quickly, Zeppelin captured ideas while they still sounded spontaneous. “We didn’t over-rehearse things,” Page emphasized. “We just had them so that they were just right, so that there was this tension – maybe there might be a mistake. But there won’t be, because this is how we’re all going to do it and it’s gonna work!”

The record sounds fresh because it is. If a song didn’t come together quickly, they simply moved on.

As Page recalled: “We’d get it up to a serious speed, so it’s really firing on all cylinders, and then you’d start recording. With the red light on there’s even more urgency to it. We’d arrive at those takes in a pretty short time – just a handful of takes, maybe. If a song started to labour, and it just wasn’t working, there’s no point in just recording it. We’d just stop it and do something else, and then return to it later.”

Guitar solos were always the last thing recorded.

“I wanted it to be totally in character of what’s going on with the lyrics and a summing up of my guitar playing for that particular song,” Page explained. “What I’d do is just limber up and then, okay, put the red light on. And again, those solos weren’t done over hours and hours. They were pretty much improvised. They weren’t worked out note for note. Never. The solos were always: take a deep breath and go for it! For the spontaneity. I might have worked out how I might start it off. But that’s it.”

With a combination of inspiration and ruthless efficiency, Zeppelin’s fourth was essentially complete by the end of their month-long residency at Headley Grange. Three tracks remained unfinished: Four Sticks (a rhythmic number on which Bonham on played with, yes, four drum sticks); Black Dog, the heavy hitter that would serve as the album’s opening salvo; and lastly, the song that many consider the greatest of all time.

“I had the sections for it. It was a question of piecing them together,” said Page of writing Stairway To Heaven. “By nature of the fact that it had acceleration through it, it needed some work on it. Definitely it was the sort of thing where you wanted to be all around each other. Because of the amount of overdubs that were going to go on it, it needed to be done in a studio.”

Returning to London, Page picked Island Studio 1 for its ambience and clarity. The rich arrangement for Stairway to Heaven includes all of Page’s main guitars. The intro was his beloved Harmony Sovereign H-1260, a budget acoustic used to write the first four albums, while the lush electric rhythms came from two different 12-strings, DI’ed and panned left and right.

His Fender Electric XII was joined by the Vox Phantom he’d used on Led Zeppelin II and earlier, in his previous band The Yardbirds, for the song Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor. They were recorded straight into the desk and compressed.

Outro riffs came from his Les Paul, while the solo was played on the legendary Dragon Telecaster, a gift from Jeff Beck he’d used to record all of Led Zeppelin’s debut. The Gibson ES-1275 double neck didn’t arrive until after the song was recorded, when Page needed one guitar that could reproduce all the parts live.

The solo used the same approach as the others, Page preparing the opening lick and a few link phrases before improvising the rest. He says the solo came together easily, in about three takes. Producer Andy Johns, however, remembered things differently in a 2009 interview with Rhythm.

“There was a bit of a struggle on the solo. He was playing for half an hour and did seven or eight takes. He hadn’t quite got it sussed. I was starting to get a bit paranoid and he said, ‘No, no you’re making me paranoid.’ Then right after that he played a really great solo.”

Page is notoriously reticent to give details of the amps used on specific tracks, sometimes complaining that after he mentions using a particular amp with Led Zeppelin they become impossible to buy.

He has variously claimed the Stairway amp was a Marshall or a Supro. We do know that his Number 1 Les Paul Standard and Marshall 1959 Superlead head remained his main rig for the Headley Grange sessions. That tone didn’t work for Black Dog, however, and Page recut those guitars at Island with Andy Johns.

Despite his association with cranked Marshalls, Page is no valve amp purist. After the bass and drums were completed at Headley, Page cut the Black Dog guitars at Island Studios, using a direct box to plug straight into the desk.

Andy Johns cranked the gain on the mic input to create distortion, and put the signal through two Universal 1176 compressors in series. The riff was triple-tracked, with one take panned left, one right, and one centre. Page has compared the resulting tone to an analogue synth.

For the solos in Black Dog, Page took a more orthodox approach. As he told Guitar World in 1993. “I wanted something that would cut through the direct guitars – I wanted a totally different tone color. So I ran my guitar through a Leslie and mic’ed that in the usual way.”

This “usual way” of mic’ing was actually pretty unusual for the time. While most engineers close mic’ed cabs, Page would position an ambient mic anywhere from six to 20 feet from the speaker, depending on the room’s sweet spot. As with Bonham’s drums, Page followed his mantra “distance equals depth” for recording guitars.

The last completed track was Four Sticks, whose intricate overdubs also required the clarity of a recording studio. Along with Stairway, Page felt Four Sticks came the closest to fulfilling his artistic vision.

We were crafting albums for the album market. It was important, I felt, to have the flow and the rise and fall of the music

Jimmy Page

He told Steve Rosen in 1977: “My vocation is more in composition, really, than anything else. Building up harmonies, orchestrating the guitar like an army – I think that’s where it’s at, really, for me. I’m talking about actual orchestration in the same way you’d orchestrate a classical piece of music.

“Instead of using brass and violins, you treat the guitars with synthesizers or other devices; give them different treatments, so that they have enough frequency range and scope and everything to keep the listener as totally committed to it as the player is. I can see certain milestones along the way, like Four Sticks, in the middle section of that. The sounds of those guitars – that’s where I’m going.”

Recording complete, Page mixed the album at Island with Johns after a disastrous ten days at LA’s Sunset Sound produced only one useable mix, When the Levee Breaks. What remained was sequencing the album – crucial for a band determined not to release singles.

“We were crafting albums for the album market,” he said. “It was important, I felt, to have the flow and the rise and fall of the music and the contrast, so that each song would have more impact against the other. I thought that Levee Breaks just had to finish the overall picture of what we’d done – the sonic picture – because it was just so ominous. After you’ve caressed them with Stairway, now you’re going to disturb them!”

Led Zeppelin IV is not just the greatest guitar album of the 70s, but the benchmark for every guitar band ever since.

Jenna writes for Total Guitar and Guitar World, and is the former classic rock columnist for Guitar Techniques. She studied with Guthrie Govan at BIMM, and has taught guitar for 15 years. She's toured in 10 countries and played on a Top 10 album (in Sweden).