Back in the 1950s, single-coil pickup noise was a big issue for players and all the major guitar manufacturers were aware of it.

Gibson employee Seth Lover had adapted a well-proven humbucking circuit for the power supply choke in his GA-90 amp design and realised the same idea could be used to make a humbucking pickup. Ted McCarty gave Seth the go-ahead in 1954, and by the following year he had a working prototype with a plain cover and flat slugs.

Seth considered P-90-style adjustable polepieces unnecessary but relented when Gibson’s marketing team argued it would give them a good selling point.

Others were working on noise-free pickups, too, with Les Paul’s guitar tech, Tom Doyle, reporting Les using a hum-cancelling dummy coil in the 1940s and winding his own stacked humbuckers. Meanwhile, in Cairo, Illinois, Ray Butts was developing a humbucker that would become the Gretsch Filter’Tron.

The first Gibson humbuckers appeared on steel guitars in 1956, but the PAF and Filter’Tron were officially launched at the 1957 Summer NAMM Show. They weren’t actually the first humbucking pickups, however.

Armond Knoblaugh devised a stacked humbucking pickup for Baldwin electric pianos in 1938, and Clarence Russell received a patent for a double-coil horseshoe pickup in 1939. Vega also used a similar design in the late 1930s.

The patents Seth Lover and Ray Butts applied for were eventually granted on the basis of their adjacent coil arrangement. Ray applied for his on 22 January 1957, while Seth Lover filed on 22 June 1955.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

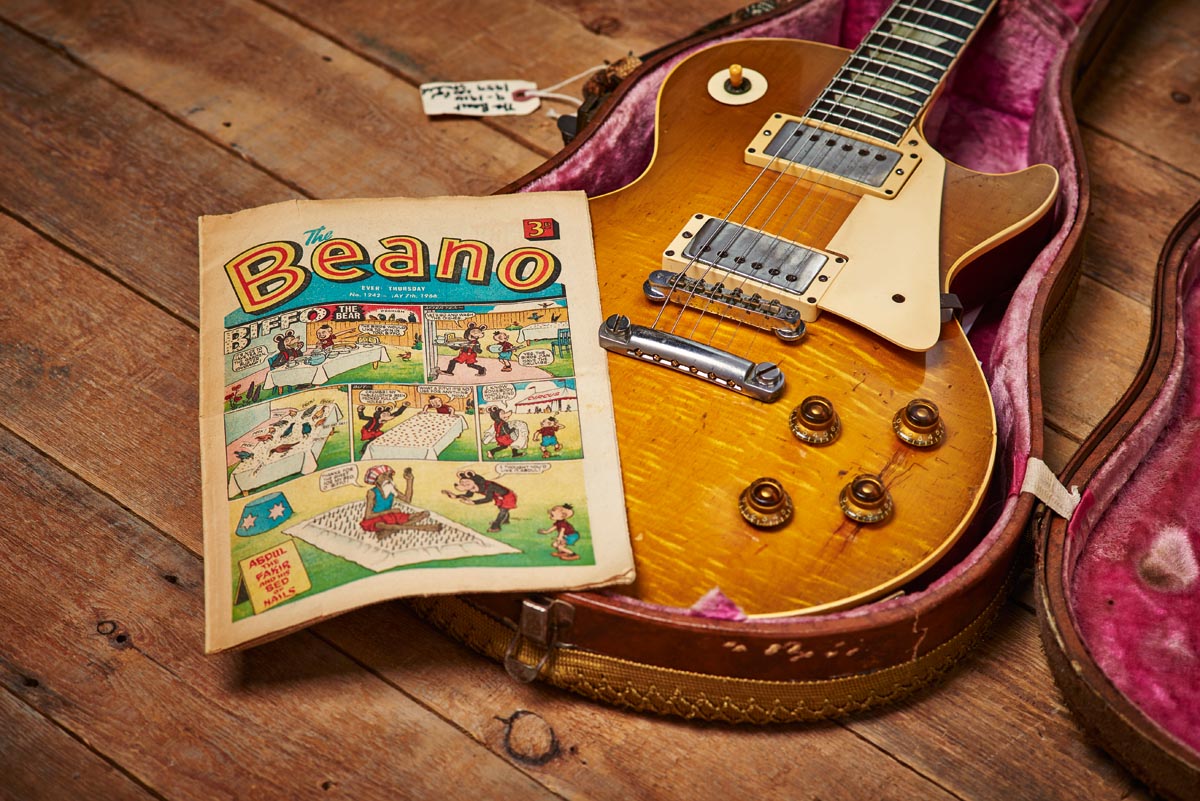

Seth’s patent – No 2,896,491 – was eventually issued on 28 July 1959, but Ray received his a month earlier. While waiting for a patent number, Gibson attached ‘Patent Applied For’ water slide decals on the baseplates on all but the earliest examples – and thus the PAF nickname was born.

This decal lasted until late 1962, long after the patent had been granted. When Gibson eventually began applying ‘Patent Number’ decals, the number actually referred to the patent for Les Paul’s trapeze tailpiece.

In brief, Patent Number pickups had shorter magnets and more closely matched coils, but during the transition period PAFs and Patent Number pickups sometimes ended up with incorrect decals.

Since the 1950s, the vast majority of humbucking pickups have been configured just like PAF and Filter’Tron units. However, the humbuckers that Gibson made between 1956 and around 1962 have a very specific set of features, materials and manufacturing anomalies that set them apart from their contemporaries. To explain what makes PAFs so different, we need to analyse the constituent parts and their complex interaction.

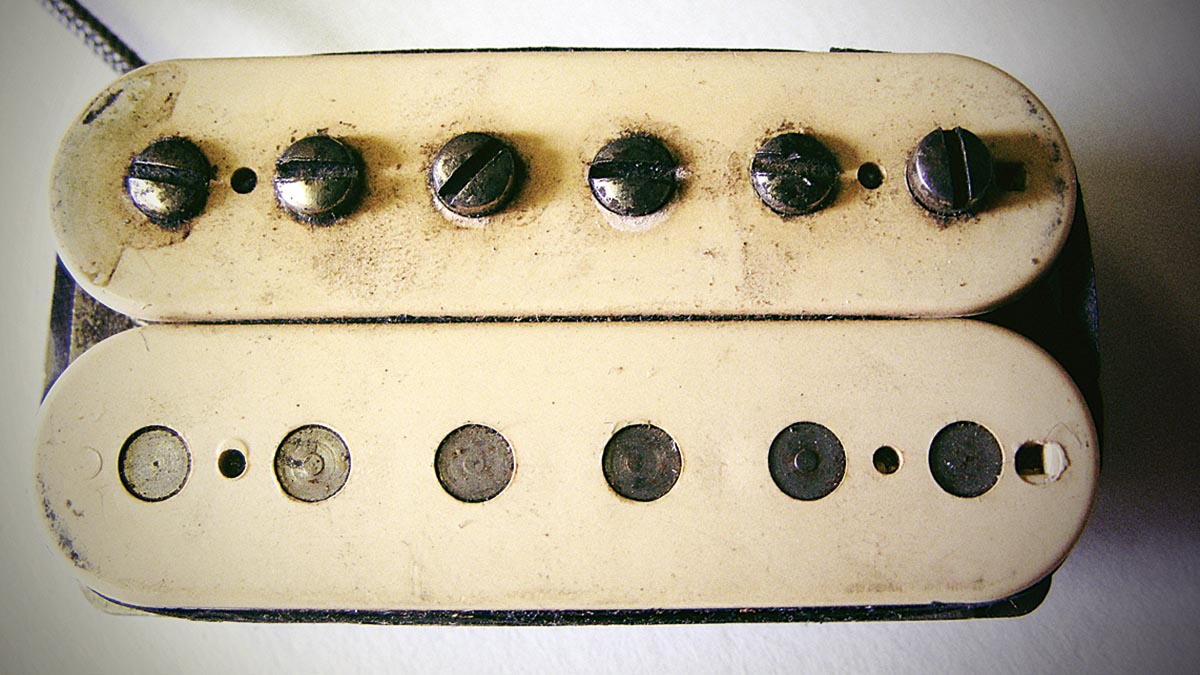

Bobbin types

PAF coils are wound onto plastic bobbins moulded from cellulose acetate butyrate (CAB). Each PAF has two bobbins, with non-adjustable steel slugs in one and fillister head screws in the other. These bobbins were originally black, but cream coloured bobbins started appearing in early 1959 due to supply issues.

Since all PAF pickups were fitted with metal covers, guitar players only became aware of the issue when removing covers became fashionable. PAFs with mixed black and cream bobbins are called ‘zebras’ and those with two cream coils are known variously as ‘double white’, ‘double cream’ and ‘full cream’.

Cream bobbins lasted until late 1960 and double whites are the rarest and most collectable PAFs of them all. It has been suggested that double whites sound hotter than other PAFs, but in the unlikely event that’s actually true, the bobbin colour itself has no effect on the output.

M-69 pickup rings were also moulded from butyrate, and if you’re trying to establish whether rings and bobbins are butyrate, you can try the ‘scratch and sniff’ test if you’re feeling brave. Why brave? Because the real thing has an unmistakable aroma of vomit…

On the wire

Gibson used AWG 42 wire insulated with a plain enamel coating. The insulation layer’s thickness has a bearing on the size of the coil and the length of wire needed for any given number of turns. A thicker coating results in fatter coils with a greater length of wire and therefore a higher DC resistance (DCR).

The company also chose Geo-Stevens, Meteor and Leesona winding machines that were most likely designed for transformer manufacture but later adapted for pickup making. Each of these machines produced coils with slightly different shapes, sizes and tightness.

Consequently, coils wound on these machines all sound slightly different. It is also known that Gibson’s pickup makers didn’t use an auto-stop, so coils were wound until the bobbin looked full and placed in a container for later assembly. These inconsistencies in the winding process were compounded when slug and screw coils were paired up randomly.

Any PAF could end up with coils wound on various machines that were closely matched, miles apart or anywhere in between. This partly explains why vintage PAFs vary from around 7kohms to 9k in terms of DC resistance and have such a wide spectrum of tonal characteristics.

Pre-CBS Fender pickups were famously ‘hand wound’, with a randomly ‘scattered’ wire distribution that equates to a clearer and brighter tone. For vintage-accurate single-coil tone, this is regarded as preferable to the uniformity that typifies machine-wound coils.

But PAFs also tend to sound very clear and bright, and the coils don’t have a machine-wound appearance. There are a couple of reasons for this. The coil’s ‘start wire’ was soldered to a thicker leadout wire that was fed through the bottom of the bobbin.

The absence of potting allows PAFs to behave a bit like microphones and capture more of a guitar’s acoustic qualities

This thicker wire was wrapped around the bobbin then taped down, and it would disrupt the winding to cause unevenness in the coil. In addition, Gibson’s heavily used machines weren’t actually designed for wrapping such thin wire, so there was always some unevenness in the wraps. As a result, PAF coils ended up having scatter‑wound characteristics despite being machine-wound.

Another key factor is that Gibson didn’t wax pot pickup coils during the PAF era. Instead, the coils were simply wrapped with tape before the covers were attached. This absence of potting allows PAFs to behave a bit like microphones and capture more of a guitar’s acoustic qualities. They also have an extra layer of ‘air’ frequencies that provides added transparency and harmonic complexity, but at high gain and volume some PAFs do squeal.

Magnetic personalities

Although Gibson company records reveal it has always ordered rough cast Alnico II, Gibson’s own analysis of vintage magnets revealed a higher incidence of Alnico III in its small sample batch. It has also been suggested that Alnico III was most common in 1957 and 1958, with Alnico II and V showing up more often from 1959 to the early 1960s. Whatever the grade, Gibson called this the M55 magnet.

While P-90s have two magnets, PAFs only have one and they’re not identical. P-90 magnets need to make good physical contact with the central steel keeper bar, so they’re only ground flat on one side.

Some of the very early PAFs had P-90 magnets, but Gibson began grinding both sides flat for a snug fit with the slugs and the keeper bar under the screw coil. Even so, P-90 magnets have occasionally been seen in PAFs throughout the vintage era.

In terms of size, P-90 and PAF magnets were initially 2½ inches by ½-inch by 1/8-inch, but during late 1959 Gibson began using shorter 2 5/16-inch magnets designated the M56. Magnets can be oriented or unoriented, and the latter provides a weaker magnetic field. Alnico II, III and IV magnets tended to be unoriented, and while Alnico V came in both forms, unoriented was more common before 1960.

The Alnico grades of today aren’t necessarily the same as they were in the 1950s – irrespective of the numbers

John Grundy of ThroBak Pickups maintains that Gibson batch-charged magnets in-house and this resulted in magnets that were unevenly charged and less stable. Complicating matters further for would-be PAF replica builders, the Alnico grades of today aren’t necessarily the same as they were in the 1950s – irrespective of the numbers.

Metal magic

The metal parts used in PAF construction include the baseplate, slugs, pole screws, keeper bar, bobbin screws and cover. Most serious PAF replica makers agree that some of these parts influence PAF tone. The baseplates were formed from German silver and the bobbin screws were (usually) brass, so those parts are non-magnetic and have no sonic effect.

In contrast, the screws, slugs and keeper bar are all steel, and analysis by Electric City Pickups, ThroBak and other pickup makers has revealed that the steel Gibson used had a very low carbon content with a correspondingly sweet and rounded tone. PAF-style pickups made with higher carbon content steel parts can sound brighter and harsher.

The earliest PAF units had brushed stainless-steel covers, but these were soon changed to a nickel-silver material and they have distinctive corners and dimples around the screw holes. Seth Lover intended PAF covers to be as sonically transparent as possible, so they’re quite thin and have just a very slight softening effect on the upper midrange.

You will generally find that gold-plated vintage parts are cheaper than their nickel-plated equivalents

The covers were nickel-plated without a copper layer underneath. The gold plating was done straight over the nickel plating, which means the gold often wears off to expose the nickel.

You will generally find that gold-plated vintage parts are cheaper than their nickel-plated equivalents. This gives you the option of buying gold hardware and rubbing the gold off with a Brasso pad.

Huw started out in recording studios, working as a sound engineer and producer for David Bowie, Primal Scream, Ian Dury, Fad Gadget, My Bloody Valentine, Cardinal Black and many others. His book, Recording Guitar & Bass, was published in 2002 and a freelance career in journalism soon followed. He has written reviews, interviews, workshop and technical articles for Guitarist, Guitar Magazine, Guitar Player, Acoustic Magazine, Guitar Buyer and Music Tech. He has also contributed to several books, including The Tube Amp Book by Aspen Pittman. Huw builds and maintains guitars and amplifiers for clients, and specializes in vintage restoration. He provides consultancy services for equipment manufacturers and can, occasionally, be lured back into the studio.

“Classic aesthetics with cutting-edge technology”: Are Seymour Duncan's new Jazzmaster Silencers the ultimate Jazzmaster pickups?

“We’re all looking for new inspiration. Some of us have been playing humbuckers for a long, long time”: Are we witnessing a P-90 renaissance? Warren Haynes has his say