Garbage’s Steve Marker: “It was important to keep the initial spirit that we had when we wrote these songs”

No Gods No Masters. That’s the title of the hotly awaited new jam-fest from the pop-rock mainstays in Garbage – but it’s also the mission statement they avowed when they gathered in the Californian desert to make it

According to Garbage frontwoman Shirley Manson, it was fitting that No Gods No Masters – the impending new long-player from the millennial pop-rock powerhouse – came at this specific point in their timeline. “This is our seventh record, the significant numerology of which affected the DNA of its content: the seven virtues, the seven sorrows, and the seven deadly sins,” she declared in a press statement. “It was our way of trying to make sense of how f***ing nuts the world is and the astounding chaos we find ourselves in. It’s the record we felt that we had to make at this time.”

The 11-track jaunt is a vicious and visceral scolding of capitalism, bigotry and political corruption, spun through the band’s ever-enigmatic web of brisk, booming pop music. Sonically, it’s a smack back to the late-‘90s heyday of mid-fi power-pop that Garbage came of age in. In a bid to rekindle their youthful vigour, the band voyaged out to the vast nothingness of the Californian desert – where for two weeks, they holed up in a house borrowed from a relative of guitarist Steve Marker, jammed up a storm, and sewed the seeds of an erratic discontent that would fuel their seventh album.

As we learned from Marker in a Zoom call, that capricious, bare-bones approach to songwriting was just what Garbage needed to reach new heights and embrace an adolescent sense of creative energy they’d thought had long since been shed. No Gods No Masters may be the album’s title, but it’s also the band’s new manta for life.

Where did the idea come from to make this record out in the desert?

Well, I think we’ve done some of our best writing when we were all together. We live all over the country and tend to do things over email or via phone, and it never is as good as when all four of us are sitting in the same little room, with some beer and a little tape recorder, just jammin’ out. When we made our first albums, we were basically living together in this really small studio in the midwest – and we were hoping to get back to that vibe.

So we had a little house that we borrowed, and we all moved in for a couple of weeks to start the writing, and we just kind of found the spark again. We would get up at the crack of noon and have a couple cocktails, and basically just start jamming. We had guitars and keys and everything set up in this little living room, and we had no preconceptions or baked-in ideas – there were no demos that people brought in, it was all just whatever happened in the moment. And I think we came out with some really great stuff!

Do you find that your surroundings can really influence your creative mindset?

I think it does, for sure. Y’know, we’d love to be able to go all over the world – you hear about all these exotic places that bands went in the ‘70s, making records in Switzerland or India or wherever – but we can’t really afford to do that. We could afford to borrow this house, though, so that’s what we did. And I don’t know, the desert is really beautiful.

I actually ended up moving here because I liked it so much. I wanted to be closer to the band. Butch [Vig, drums] and Shirley [Manson, vocals] live in LA so I was planning to move out there, but then the pandemic hit so I ended up here in the desert. But it’s great – it kind of gives you an open mindset, y’know? It’s a big, wide horizon with not that much in the way, and I think that frees you up to be really creative in a way.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How much material did you come out of those desert sessions with?

There are six or seven songs on the album that got their start in those first few days. And there’s a couple that didn’t get changed much at all after that. There’s one called “Uncomfortably Me” that was basically done there on the spot – we just felt like it had a good vibe, and that was it.

Things tend to get reworked a lot after we finish the initial sessions – y’know everybody’s got their little home studios and everybody keeps tinkering all the time, trying to make things better – but I think it was really important to try to keep the initial spirit that we had when we wrote these songs. And a lot of the stuff Shirley came up with off the top of her head, as far as I know, a lot of those ideas are right there on the record.

Do you reckon you can hear that spontaneity in the final product?

I certainly hope so! I think that spontaneity is what goes with the moments that people latch onto when they hear a record. You can rework things to death – and I’m sure it’s the same as writing for you, y’know, you can do things over and over so much that a story kind of loses its spark. We’ve been around for a while now, obviously, and I think some of our better moments were the ones that got done really quickly, without a lot of thought. It’s always more about feel than thought.

One of our first singles, “Stupid Girl” – we came up with the basic music for that in about ten minutes. There wasn’t a lot of worrying about what was going to happen, or going, “Is anybody going to like this?” We just did it, and we put it out because we liked it. And hopefully we’ve gotten back to that attitude – we’d been trying to for years, but I think we were actually successful on this album.

What was your studio setup like in the way of guitars?

So it was recorded in Shirley’s husband’s little… It’s hardly even a studio. It’s a mix room, but it’s just crammed full of lots of weird gear. He tends to collect these bizarre, old, like, ‘60s and ‘70s Japanese guitars. He’s got this huge pile of weird shit. We tend to go for something that’s got a real vibe to it, rather than the newest shredder guitars – because those guitars might be set up perfectly and look beautiful and everything, but they have no personality. If something is beat-up and kind of offbeat, that’s probably what we’re going to pick up.

We’ve got some old Fenders that we used quite a bit. Billy [Bush, producer] has got this incredible 1960s Strat that actually has B.B. King’s autograph scratched into it with a nail. It’s always more inspiring to play the weird shit like that. But definitely Telecasters – they’re something we use all the time.

I really like the EOB Strat with the sustainer circuit in it; I used that in the way you might typically use a keyboard pad. And I’m really excited because in the next couple of weeks, I’m getting my own to use for our summer tour. That’s a really fascinating instrument for me – I love to think about what I could do with that kind of thing. It’s kind of like having an e-bow built into your guitar.

One other thing I was going to mention is that Billy’s got a Maton from one of our trips over to Australia – he’s got a beautiful guitar that they made for him when we were over in Melbourne – and we used that a bunch, too.

Ellie Robinson is an Australian writer, editor and dog enthusiast with a keen ear for pop-rock and a keen tongue for actual Pop Rocks. Her bylines include music rag staples like NME, BLUNT, Mixdown and, of course, Australian Guitar (where she also serves as Editor-at-Large), but also less expected fare like TV Soap and Snowboarding Australia. Her go-to guitar is a Fender Player Tele, which, controversially, she only picked up after she'd joined the team at Australian Guitar. Before then, Ellie was a keyboardist – thankfully, the AG crew helped her see the light…

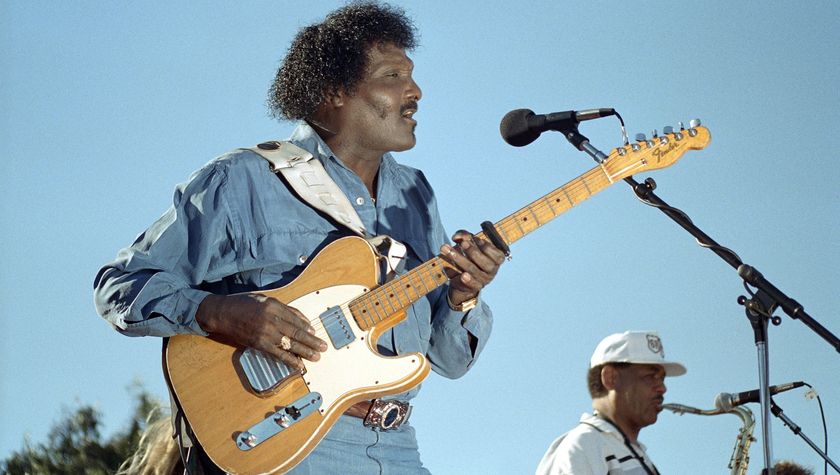

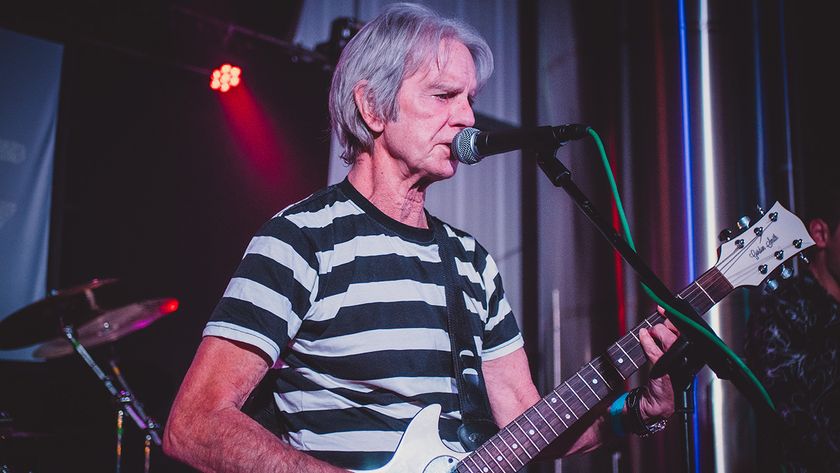

“I get asked, ‘What’s it like being a one-hit wonder?’ I say, ‘It’s better than being a no-hit wonder!’” The Vapors’ hit Turning Japanese was born at 4AM, but came to life when two guitarists were stuck into the same booth

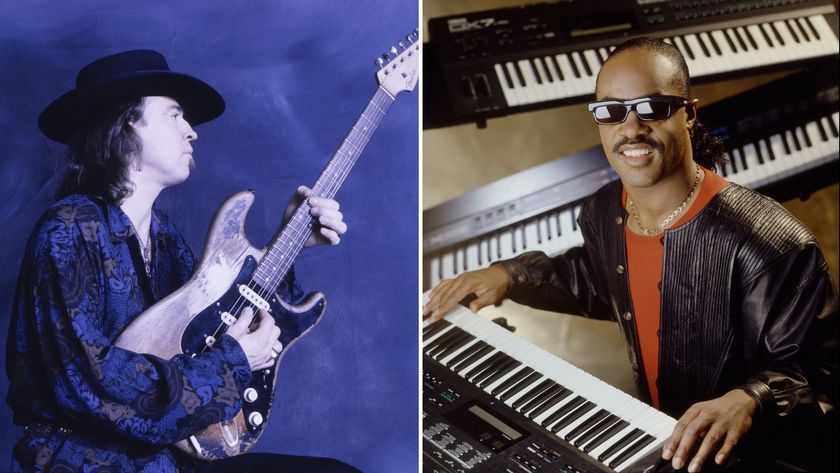

“Let's play... you start it off now, Stevie”: That time Stevie Wonder jammed with Stevie Ray Vaughan... and played SRV's number one Strat

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)