Fontaines D.C.: ”We’re not great musicians but we can play a three-chord song and give it some welly”

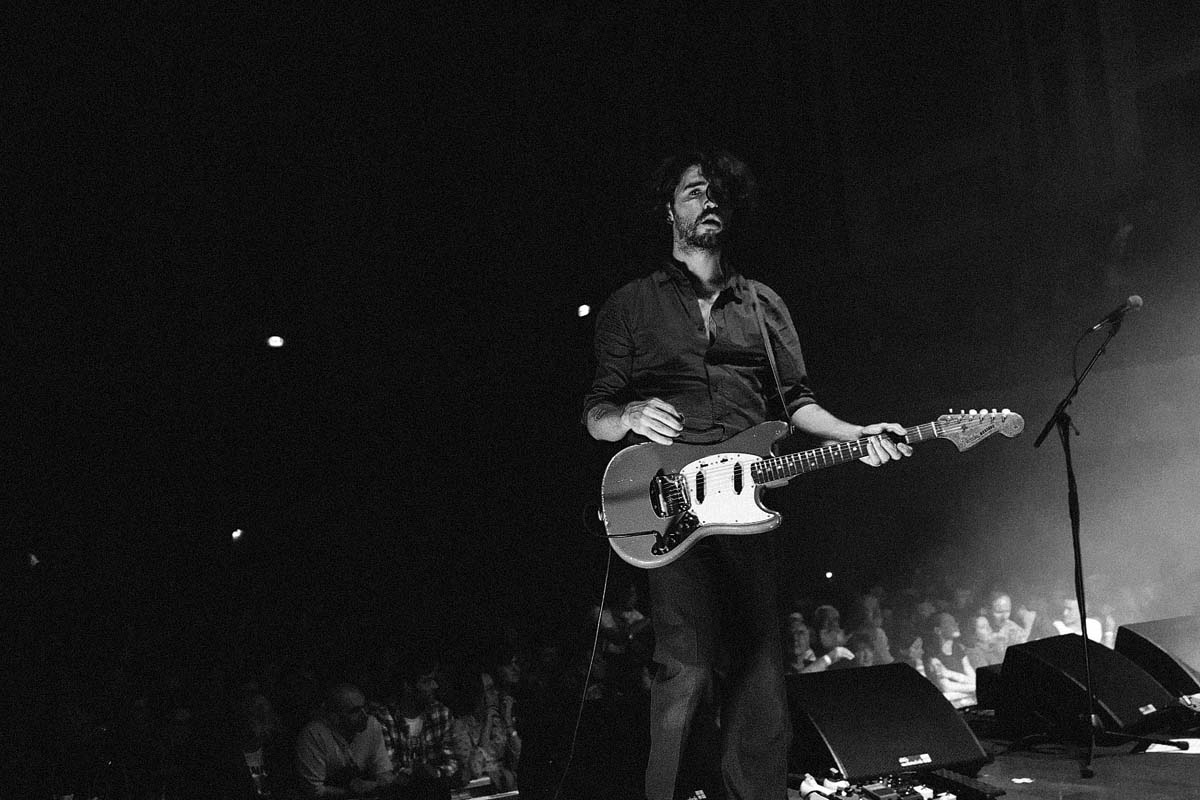

Carlos O'Connell and Conor Curley detail their unorthodox pedalboards, scuzzy tones and why they recorded A Hero’s Death twice

IT’s little more than a year since their debut album came out, but Fontaines D.C.’s lives are unrecognizable from the scrappy newcomers that began 2019.

That album, Dogrel, was universally acclaimed and landed top 10 chart positions on both sides of the Irish Sea. Upon its release, they were playing pubs in their native Dublin; their last show before lockdown was to a sold out Brixton Academy.

Anticipation was at boiling point for their follow-up album, A Hero’s Death. They narrowly lost a chart battle for the #1 slot to Taylor Swift, despite lacking Swift’s enormous PR muscle and being unable to do any promotional gigs.

It’s hard to avoid clichés about whirlwinds and rollercoasters to describe such a rapid rise to stardom, but as guitarists Carlos O’Connell and Conor Curley (known to all by his surname) told us, it wasn’t easy to get here.

We recorded the album twice. We had this idea that we were going to sound big, thinking of the Beach Boys. When we recorded it, we realised that the songs weren’t written to sound like that

Carlos O’Connell

A Hero’s Death is a moody album, written by a band struggling with sudden success. “I think on this record we were all in a pretty bad place writing it,” explains Carlos. “We were touring loads, and far away from people we love and home. Our lives just changed really quickly.

“We went from being a band around town, and we were excited about everything we did but no one else was, to suddenly everyone was excited about it. We were flooded in with shows non-stop. We all became kind of sheltered and didn’t talk about how we were feeling about it.”

The resulting songs were understandably darker. “You think, ‘I feel like shit, but I’m living my dream, maybe I shouldn’t be complaining’. We ended up holding in this negative energy, and the only thing we had to escape that was writing these tunes,” says Carlos.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

To express their emotions, the band started listening to proto-goths The Birthday Party and synth-punk pioneers Suicide, who influenced the writing of A Hero’s Death. But the band had also been taking inspiration from the Beach Boys, and they headed to LA with plans to make a sunny record.

Carlos continues: “We recorded the album twice. First time we did it in LA at Sunset Sound studios, so it was all big and grand and loads of gear. We had this idea that we were going to sound big, thinking of the Beach Boys, the 3D aspect with all the different layers.

“When we recorded it, we realised that the songs weren’t written to sound like that, even though we were trying to convince themselves that they were. The songs sounded quite flat and quite boring actually when they were weren’t true to the darkness in them.”

Hastily refocusing, the band returned to London with Dogrel producer Dan Carey. He had shown his ability to capture the band as they truly were on the debut, and together they recreated the vibe of the band’s live demos. After such a difficult birth, it’s a relief to find that Fontaines D.C.’s second album is a triumph.

“Everyone’s really into it,” enthuses Curley. “We told fans not be disappointed if it wasn’t Dogrel Part Two, but the reaction has been very good. People have gone with us and have given us the chance to develop in our own way.”

A Hero’s Death is a guitar-driven album, but both guitarists have a utilitarian approach to gear. “I’m into whatever gear I use. Outside of that I don’t really pay that much attention,” observes Carlos. Curley agrees, “I have a real love for guitars and vintage gear, but it’s almost like a separate hobby. I treat my own gear as just kind of like practical tools that just get the job done.”

For a month I was having an existential crisis after spending all that money on, like, a kid’s guitar

Carlos O'Connell

On this album, those practical tools were almost exclusively Fenders, for both guitarists.

Curley used a Johnny Marr signature Jaguar and a ’66 Coronado II into a reissue ’68 Custom Twin Reverb, while Carlos used Dan Carey’s 1975 Deluxe Reverb amp, attacked with his newly acquired ’66 Mustang, whose 3/4 scale length came as a bit of a surprise: “It was an accident that I bought a guitar this small. I saw it online and I got someone to pick it up for me in New York. In the picture you couldn’t tell that it was that small.

“For a month I was having an existential crisis after spending all that money on, like, a kid’s guitar. But then I fell in love with it, cos it has a very different sound to a normal scale guitar, and I love the small frets.”

Guitars are always chosen for a specific purpose. Curley’s Coronado II is chosen for its hollowbody tone: “We think that we should have acoustic a lot but we play so loud that putting in an acoustic on stage just isn’t possible.”

Carlos, meanwhile, has a Fender 60th anniversary Jazzmaster prototype with a unique sound: “It gets really bassy and woolly. So for songs like Living in America which have that deep low end on the guitar, that guitar is perfect. I can’t really get that with anything else. I use the Jazzmaster for the really dark stuff. There’s no brightness in there at all, it’s amazing.”

The secret to the Fontaines D.C. sound lies in a reverb pedal made by boutique Dublin builder Moose Electronics. Carlos remembers, “When I joined the band, a guitar shop told me to go and see Moose. He made me this tiny reverb pedal with one knob.

“Curley started using it in the studio because he didn’t have a reverb, and when we tried to recreate those sounds live we realised it was all in that pedal. It has this really strange tail that breaks up. So we both have that at the start of our pedalboards.”

Wait... At the start of the board? “We didn’t know what we were doing!” laughs Curley. “Somebody told me you were supposed to put reverb after distortion so I changed it, and it just didn’t sound right. Whenever a new tech starts working with us they’re always like ‘You should change it’, and we’re like, ‘Can’t change it. It’s the core of our sound!’”

On singles like Hurricane Laughter, the distortion after the reverb creates almost a clipped slapback effect. Once you hear it, you’ll spot it all over the band’s recordings.

Curley also owns a Moose delay, which he uses for self-oscillation effects at the end of Too Real: “I think that’s one of my favourite things about his pedals, that they can descend into madness sometimes.”

His favourite pedal is the Strymon Deco, whose simulated tape overdrive gives him the grit he needs when he can’t crank up his Twin Reverb. The Deco also provides modulation on songs like Television Screens.

We ended up holding in this negative energy, and the only thing we had to escape that was writing these tunes

From here the signal goes to a JHS Morning Glory (“That’s my second, more-distorted kind of rock ’n’ roll sound. I used to have a Soul Food. I really liked the Soul Food, I have no idea how Carlos ended up having it”) before heading into a ProCo Rat or Electro-Harmonix Op-Amp Big Muff. “I’ve started using fuzz on a few songs. I like how it sits in the mix more than distortion for some tracks.”

The final touches are a Thorpy [Chain Home] tremolo, and finally an Electro-Harmonix POG2, used for an octave up at the end of Lucid Dream along with two Moose delays. “I just want to screw up the end so I put all the effects through it.”

Pedals can be an integral part of the band’s songwriting, as Carlos explains: “Sometimes a pedal writes a part. In Televised Mind I play the descending lead line, and there’s this percussive tremolo like tak-tak-tak. When I got that Moose tremolo, I got really excited because of the different rhythms you could create against the drums.

“I don’t think I would’ve played a part as simple as that, just one single note at a time, if I didn’t have that rhythmic pattern afterwards that plays so well with the drums.”

Carlos’s board also features appearances from the JHS Double Barrel, the aforementioned EHX Soul Food he nicked off Curley, and a Boss TR-2: “It sounds just like the tremolo on a Fender Twin.”

Although there are several dirt pedals on his board, most of the overdrive on A Hero’s Death is from the Deluxe Reverb amp cranked to breaking point.

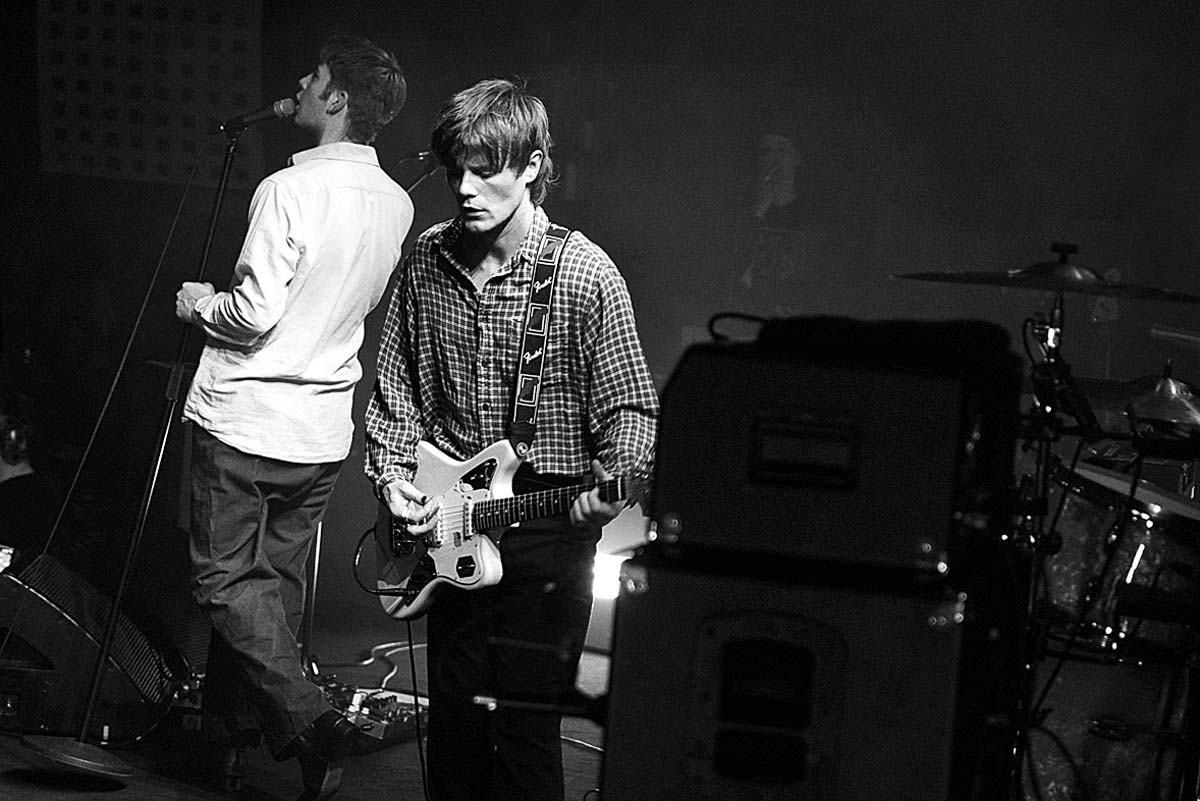

The band’s approach to playing is straightforward and simple, a reaction to the virtuosity in the Dublin scene when they formed. As Curley remembers, “The birth of Dublin neo-soul had come around. We were trying to go against that and say, ‘We’re not great musicians, but we can play a three-chord song and give it some welly.’”

“It just seemed like people appreciated more what was technically complicated. Everyone aspired to write all these amazing harmonies or all these chord progressions that were going through all these different keys. We were really put off by all that,” Carlos adds.

The band plays to their strengths, nailing simple parts with authority like their heroes the Velvet Underground: “That imperfection, the guitar tone being so jagged and recorded kind of badly was a huge influence on us. Whenever we were writing songs we were like, ‘What would the Velvet Underground do?’ Just being comfortable with a janky, sh*tty sound being the vibe of the song.”

On A Hero’s Death, inspiration comes, surprisingly, from country music. As Carlos puts it: “The guitars were more influenced by cowboy guitar lines and [American singer-songwriter] Lee Hazlewood, and through that [The Birthday Party’s] Rowland S. Howard, who took Lee Hazlewood and screwed it up loads.”

Curley chimes in, “On a lot of the songs it was a race to who could play the most cowboy-ish line, and whoever won got to play the part.”

Other reference points were Johnny Marr on Oh Such A Spring, the Brian Jonestown Massacre and the Beach Boys, who “encouraged us to dig deeper without having to overcomplicate things. To be able to create arrangements that are a lot deeper but still to the point.”

The Beach Boys might be an unlikely reference point for such a dark album, but the band plays with the resulting tension on the title track: “It was deliberate to create a juxtaposition between this uplifting message and music that’s quite doomy.

Curley’s got this right hand that’s like a hammer, you know

Carlos O'Connell

“At the bridge section where the ‘bap bap bap’ backing vocals happen, just this innocent piece of arrangement, very much like the surfier Beach Boys tunes, the music is at its most intense. So there is a conscious quest for that presentation of two completely different worlds to really exaggerate how far they from each other,” says Carlos.

The guitars are arranged carefully, and it’s rare that both guitarists play the same part. Despite that, there’s no clearly defined lead or rhythm role for either of them.

Typically whoever writes a part will play it, but sometimes it turns out that the other player is right for the job: “On I Was Not Born, I started playing the intro, and my style of playing is a lot messier than Curley’s. Curley’s got this right hand that’s like a hammer, you know. And we wanted that attack, so Curley recorded it.”

It’s a real loss that having made an album that captures the band’s live energy, they haven’t had the chance to perform these songs live.

As Curley puts it: “It’s the one part of your day that’s truly gratifying and you feel good about yourself. Once you don’t have that for a long time, you start going crazy. At gigs, the songs become the live versions of those songs, with different energies from different shows. I do miss that, not knowing where things are gonna go sometimes when we play live.” Carlos agrees. “I can’t wait,” he says. “I’m really, really dying for it.”

- Fontaines D.C's new album, A Hero's Death, is out now via Partisan Records.