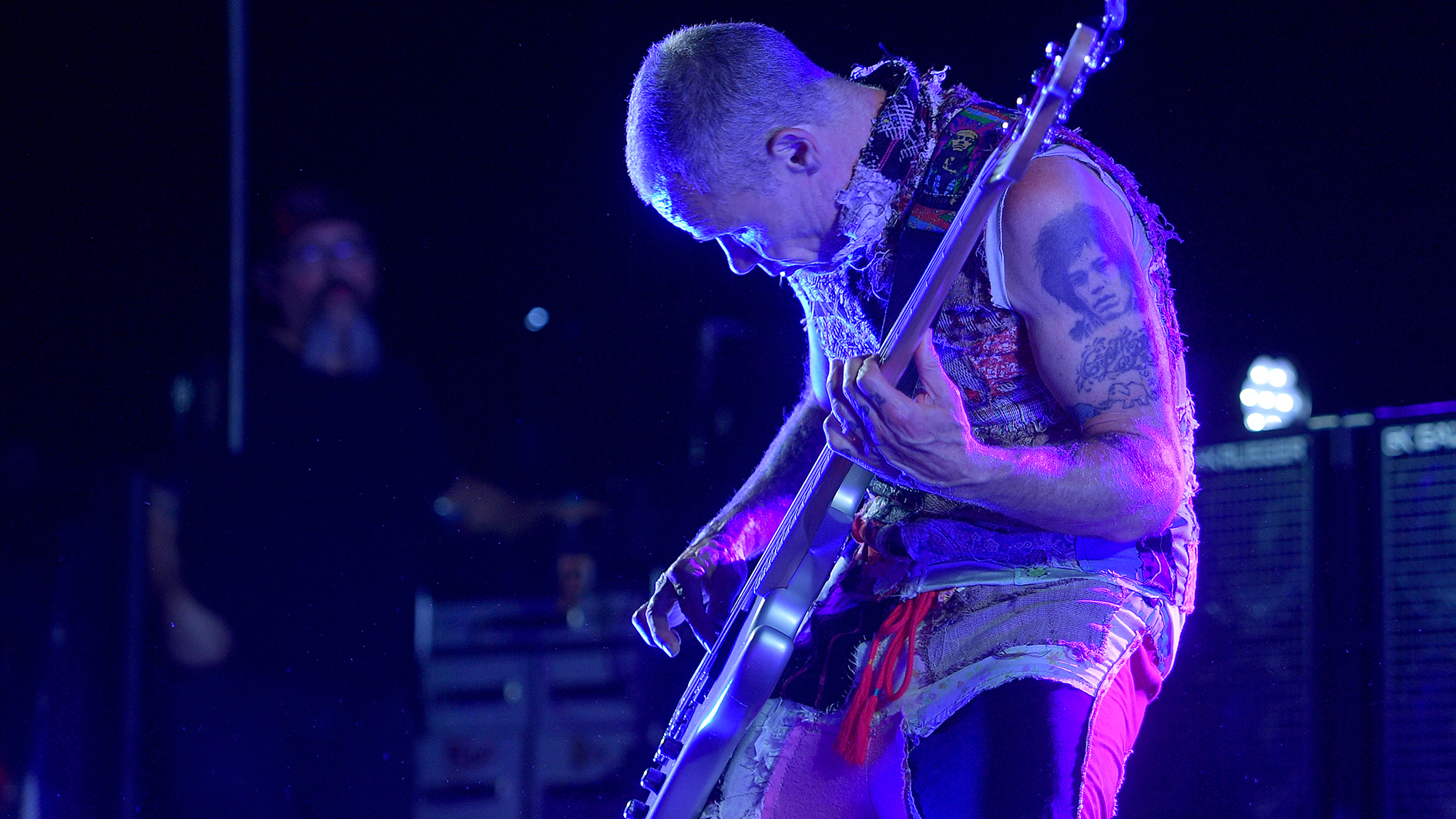

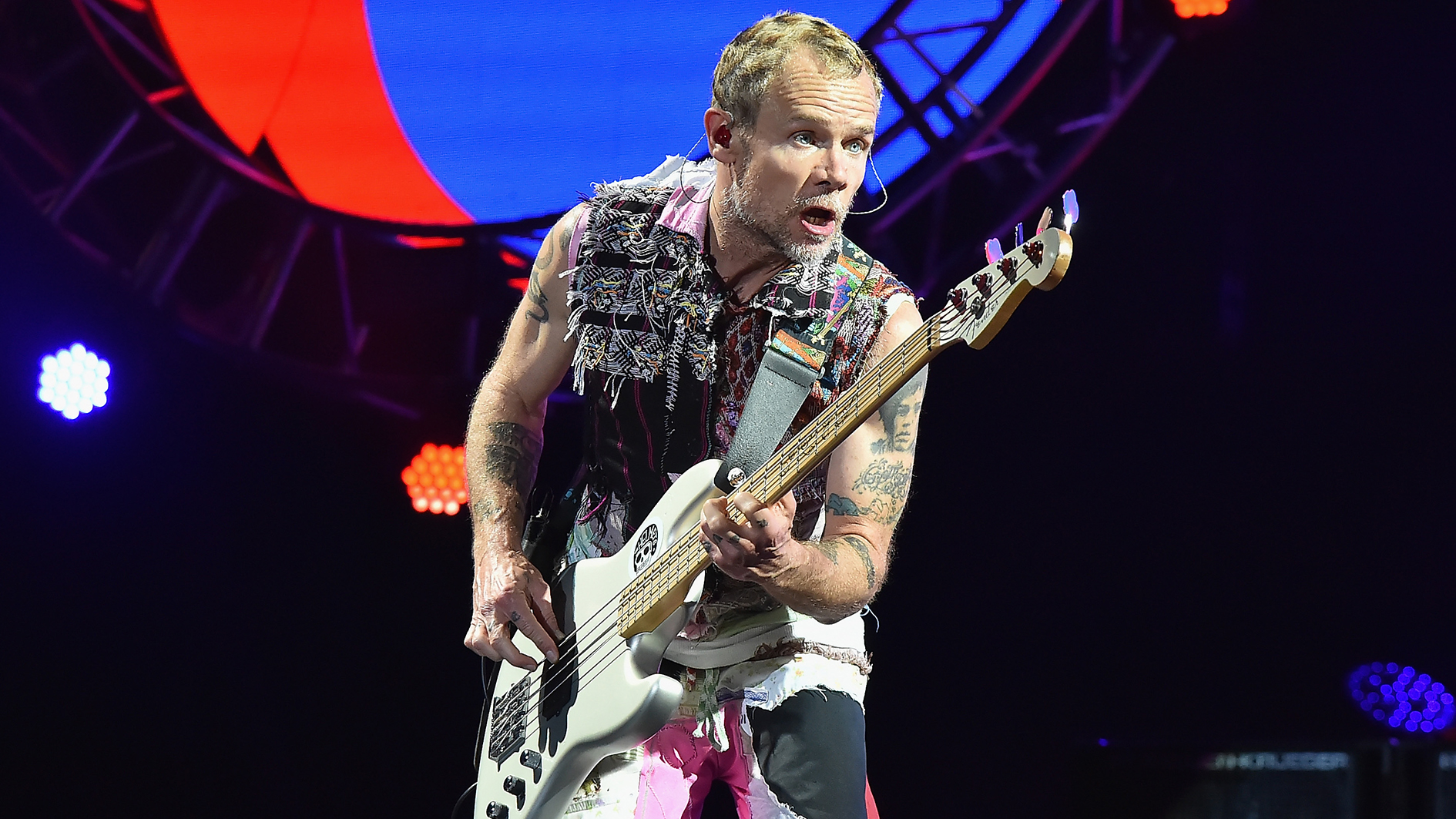

Flea: "Playing bass gets you into this hypnotic state - you’re not thinking because you’re just a conduit for the rhythm"

The iconic Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist discusses philosophy, gear and his new autobiography, Acid For The Children

"That’s a whole lot of reading, man,” observes Michael Balzary, as nobody calls him, informed to his evident surprise that I read his new book in a couple of hours. The reason for this is that Acid For The Children, out as you read this interview, is an easy read. Dealing with the Australian-born, California-raised bassist’s life from birth until 1983 or thereabouts, his autobiography is split into short chunks, some only a couple of paragraphs in length, so it’s simple and fun to digest.

The much bigger point, though, is that in Acid For The Children Flea, as everybody calls him, speaks to and connects directly with the reader. This is no easy feat, but he pulls it off, drawing you into his early life - an intoxicating but unnerving blend of unreliable parents, and the beauty of nature - and beyond.

From Oz to America, Flea veers through events big and small, recounting each with equal intensity, and surreal humor, warmed by jazz, inspired by basketball, and transformed by the loves of his life, punk rock, and the bass guitar.

It’s a hell of a read, we tell him. “Thanks, man,” says Flea. “It kinda started off as a big wild rant. An editor advised me that ranting is a good style, but that a simpler rhythm can communicate things just as profoundly, and make them easier to read, to help you connect with people. That was good advice.”

The book ends just as the early line-ups of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, with members drawn from various early bands, get their act together. Was it always his plan to split his life story into two, or did he just start writing and see what happened?

He pauses to consider, before replying: “I did just start writing and see where it landed up - but when I started I was going to write the whole story, all the way through until now, or at least until the year 2000. But actually, before that, I had thought that I would only write about the band: I wouldn’t write about myself at all. It would just be my story of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, but as I got going, I fell in love with the idea of just writing about my childhood, because that’s the thing that I could have a degree of objectivity about.

When you look at anything honestly, even your most fervent beliefs, everything has two sides to it

I wanted to write a piece of literature that could stand on its own. I liked the idea of leaving out all the rock star stuff.” Depending on your point of view, there’s plenty of ‘rock star stuff’ in Acid For The Children. There’s a bit of sex; there’s tons of drug-taking, from PCP (“like inhaling death”) to heroin, and beyond; and there’s masses of rock ’n’ roll, broadly speaking, with hundreds of references to all kinds of influential music.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But he’s right, though - the focus isn’t on extravagance in the Mötley Crüe sense, it’s more about Flea’s vivid experience of the world and all its joys and horrors, viewed through the prism of his standpoint as a confused, isolated 1970s kid. “It’s hard to look at yourself honestly,” he muses.

“When you look at anything honestly, even your most fervent beliefs, everything has two sides to it. It’s a very vulnerable feeling to do that, but I thought that for me to write an honest account of my childhood, for it to have any impact at all, I really had to write about the things that shaped me.

And as much as it has to do with joy, and the love of music, and art, and all these wild things that happened, it has to do with the pathetic and embarrassing parts of being a human being, and things about myself that I don’t like.

So it was a hard thing to do - but I promised myself that I would be completely honest, and I would write about the things that really shaped me.”

Was the experience therapeutic, we ask?

“It was, yeah. I learned about myself in writing about it a lot, and it also engaged part of my creativity that I hadn’t really engaged before, just through the process of writing itself.

"I’d been writing music since I was a teenager, but writing words is different. I would sit down with a pen and paper in the morning and start writing, maybe write for an hour or two, and when I would bring my head up from writing, I would always feel like ‘Wow, that was time really well spent’, I had a feeling like I’d done something worthwhile.

"Whether I’d been writing a memoir, or writing a poem about an ant that I saw crawling on the sidewalk, the process of writing woke me up to a part of myself that I really like. I fell in love with writing.”

Pain, turmoil, angst and anxiety are very difficult, but if you can deal with them in a conscious way, they can be the fuel for a motor to create beautiful things

A pivotal point in the book comes when the young Flea witnesses his stepfather Walter, a deeply troubled man, playing amazing jazz parts on an upright bass. Reminded of this, he says: “When I saw that really hard, swinging, fast bebop from him and his friends, who were just set up in a lounge, it opened up something in me that I didn’t know existed.

"It was so thrilling and exciting and it engaged me intellectually, spiritually, emotionally, physically... all these things all at once. It was so great for my life... but also he was a difficult guy.”

This is an understatement to say the least. You can read Flea’s description of Walter for yourself in the book, but the words ‘psychopathically violent’ wouldn’t be exaggerating in his case.

“Yeah. Very difficult!” chuckles Flea. “But it really taught me about the duality of things - the difficult things and the happy things. It taught me how pain and turmoil and angst and anxiety are very difficult, but if you can face them and deal with them in a conscious way, they can be the fuel for a motor to create beautiful things, as well as for personal growth, you know.

When you can look at those things honestly, that’s really where all the growth is in the world. I learned those things instinctually as a kid, even though I wasn’t able to process them or intellectualize them or understand them in any way until I was much, much older.”

Walter took pride when I became a bass player like him, but I think he pigeonholed the rock music as a simplistic form

Is Walter still alive?

“No, he passed away about five years ago. We had fallen out of touch, you know, the last maybe 10 years of his life. He and my mom split in the mid '80s.”

Was he supportive of your career?

“He was happy that I played, but also he had that jazz musician’s thing where you look down at rock music, you know, and I think he would have much preferred it if I’d been playing trumpet in a jazz group or the LA Philharmonic or something.

He appreciated it, I think, and took pride when I became a bass player like him, but I think he pigeonholed the rock music as a simplistic form.” We all go through that, if we like jazz.

“Yeah. Totally! As a kid I was like that. I looked at rock music and I thought it was music for dumb people, you know, but then I discovered punk rock after high school, and everything changed.”

Flea talks about Les Pattinson of Echo & The Bunnymen as an influence on bass - a reference point that might not seem obvious at first. After all, the Bunnymen’s dark, English indie is a world away from the Chili Peppers’ tartrazined funk brew, but as he explains, there’s plenty of common ground.

“I had an experience when I took acid, and saw Echo & The Bunnymen right before their album Heaven Up Here (1981) came out,” he says. “That music really affected me. I loved that band, and I especially loved their first few records. It was really powerful music to me, and for whatever reason, wherever I was in my life at that time, I really connected with it.

"The way that Les played bass was not complex or virtuoso, but it was so supportive, and so hypnotic, and so conducive as a catalyst for all these beautiful psychedelic things to happen. The way they pieced together their songs, it wasn’t all verse, chorus, bridge, they were tapestries of rhythm for psychedelic explorations to happen over, and poetical things by Ian McCulloch.

When we do jams in the Chili Peppers, I still play Les Pattinson's bass-lines all the time

I really loved it, and I used to just copy his bass-lines and play them all the time. When we do jams in the Chili Peppers, I still play his bass-lines all the time.”

Was Peter Hook an influence too?

“Absolutely! I love the way Peter Hook plays. Me and John Frusciante and Josh Klinghoffer [current and former RHCP guitarists] had a Joy Division cover band for a while. I was trying to learn how to play with a pick, because I never played that way, and I’d play all the old Joy Division basslines.

"It was such a unique style: A melodic, hypnotic way of playing bass. Jah Wobble too - all that Public Image stuff, from the Metal Box period in particular, really blew me away. Me and John always used to play ‘Poptones’ from that record.

"I love that music. I got really into that post-punk sound out of England. It was a big thing for me. It really dovetailed perfectly into jazz, and fringe art music, and punk rock: The music was so relentlessly hypnotic, and had the things that I liked about jazz and punk rock, and poetry and literature, all at once.”

Flea talks a lot about his Australian roots in the book. Was any Aussie music influential? “I’m a really big Nick Cave fan,” he says. “The Birthday Party and the Bad Seeds and all his various incarnations, that was all music that resonated powerfully with me. That’s probably the biggest one, although I love the Saints, and I love AC/DC.

"Midnight Oil too, the Chili Peppers opened up for them early on. INXS is a great band as well. My connection is to the earth in Australia and the nature, and certain aspects of the Australian character - it’s strong and rough, but at the same time it’s a real easy-going and connected character that I love. I love Australia and I’m proud to be an Australian.”

So when can we expect part two of his autobiography? Not soon, he replies: “I wrote the whole thing, all the way through, but I’m not exactly sure what I’m gonna do. I go through different feelings about it, so I’m gonna look at it and think about what kind of shape I want it to take."

Everybody feels disconnected at times, doesn’t know about their place in the world, feels uncomfortable socially, feels like they can’t relate to anyone, and that their truth is a separate truth to anybody else’s

We chat about the pace of modern life and how so few of us have a moment to think, which leads the conversation towards a standalone chapter of Acid For The Children in which Flea explains, unhurriedly, and rather pessimistically, how he often feels isolated from people to the point of complete disconnection.

I’m interested to know if this is a constant feeling on his part, or if it fluctuates, as it does for many of us. “It’s always been a thing that’s come and gone,” he explains. “Everybody feels disconnected at times, and doesn’t know about their place in the world, and feels uncomfortable socially, and feels like they can’t relate to anyone, and that their truth is a separate truth to anybody else’s.

"I think that it’s a healthy thing, even though when you’re in the process of feeling that way, it’s not pleasant. Throughout my life I’ve dealt with a lot of anxiety and panic attacks, and extreme senses of discomfort from just being in my skin, you know, or I feel judged, or I judge myself. For various reasons, healthy, and unhealthy ones, I feel disconnected. I try to make sense of it, but as I wrote about it, I began to feel like everyone feels this way to some extent in their lives.

"In writing about it, maybe it can help us all to feel less lonely.”

As bass players, we suggest, maybe the fact that we often inhabit a groove helps us to connect with people? Perhaps that’s a solution to this feeling of isolation.

“Absolutely,” Flea affirms. “That’s kind of what my book is about. It’s about feeling isolated, feeling alone, and yearning to connect; yearning to feel comfortable in myself, and yearning to create, to build bridges, and to feel real love and meaningful relationships with nature, people, and art.

Serj Tankian from System Of A Down once said to me, ‘There’s two types of people: those who know that we are all connected, and those who don’t’

"That yearning, communicated through playing music, or whatever other art form I might involve myself in, is where the greatness and the connection is. Maybe some people have a connection that might look good from the outside, but it might not be an honest connection; you don’t know what anyone else is going through, but my discomfort and my yearning to connect are where I might find real meaning.

"I’m trying to be grateful for everything, including the discomfort, in my life.”

This suggests the objective of the human species is to remove all barriers between us, an idea Flea readily endorses.

“Serj Tankian from System Of A Down once said to me, ‘There’s two types of people: those who know that we are all connected, and those who don’t’. He articulated a thing that I’ve always thought, and which lots of us have always thought. Muhammad Ali had a poem, ‘Me. We’, which was the same kind of thinking.

Every time that we get away from that, is when we cut out all our power and all our connection to the power of humanity, and to our humanity.” Warming to his theme, he adds: “We’re always looking for the humanity in things.

"We have a chance to feel some sort of enlightenment on this earth, and we have a chance to shine a light in this world, that is so full of hypocrisy and unjust behavior and cruelty and meanness, you know. If we can actually shine a light from that feeling of connection, we might have actually done something worthwhile with our lives.

"Everything worthwhile in our lives is in that knowing and that oneness and that yearning to connect, in the face of a lot of cruelty.”

On a related note, there’s a part in the book where Flea talks about a deep connection to one of his early basses, talking in detail about the feel of the neck and the metal strings under his fingers.

Every time I look at my '61 Jazz bass I’m amazed. It’s like looking at a great Picasso or an incredible thousand-year-old tree

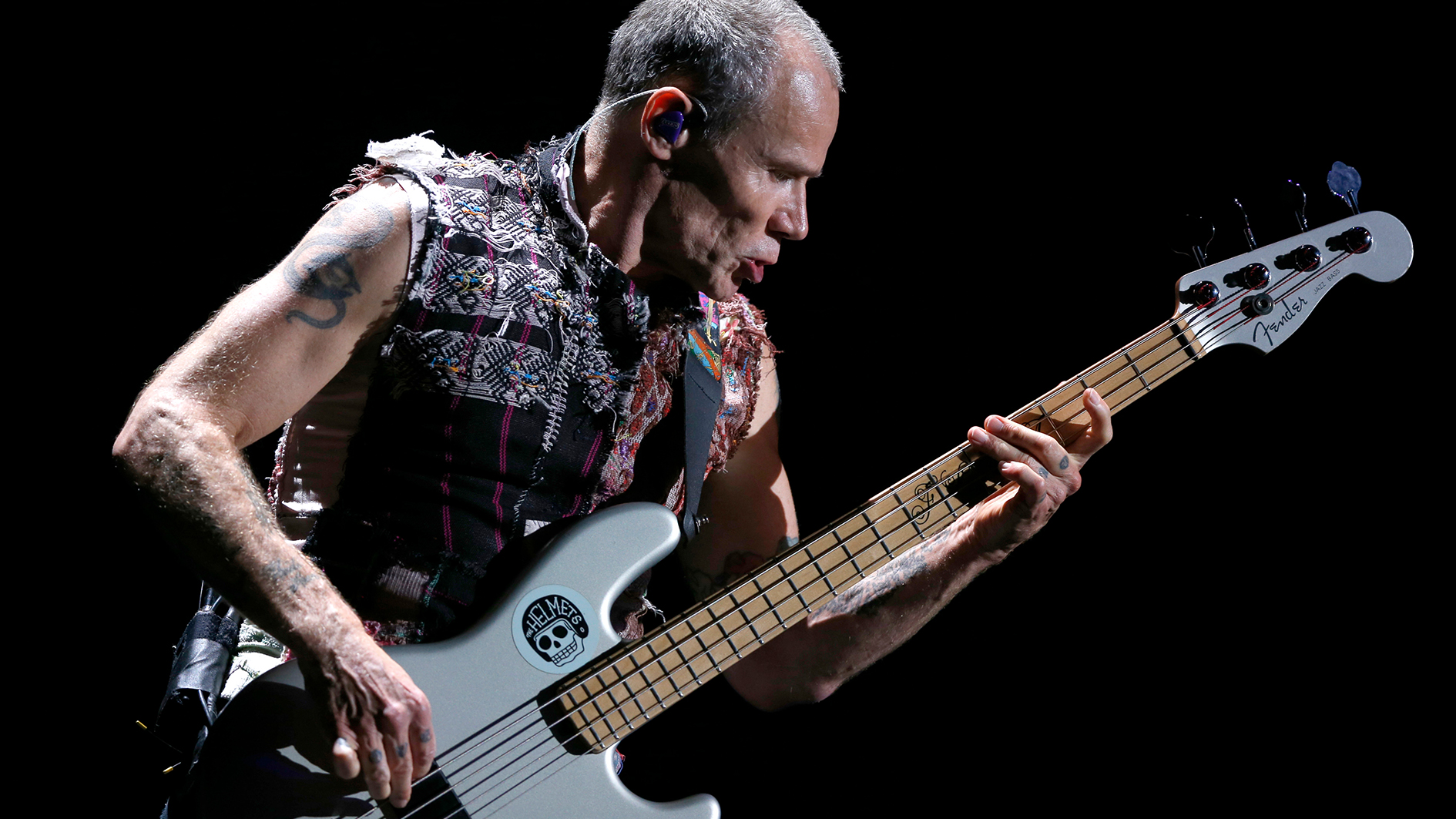

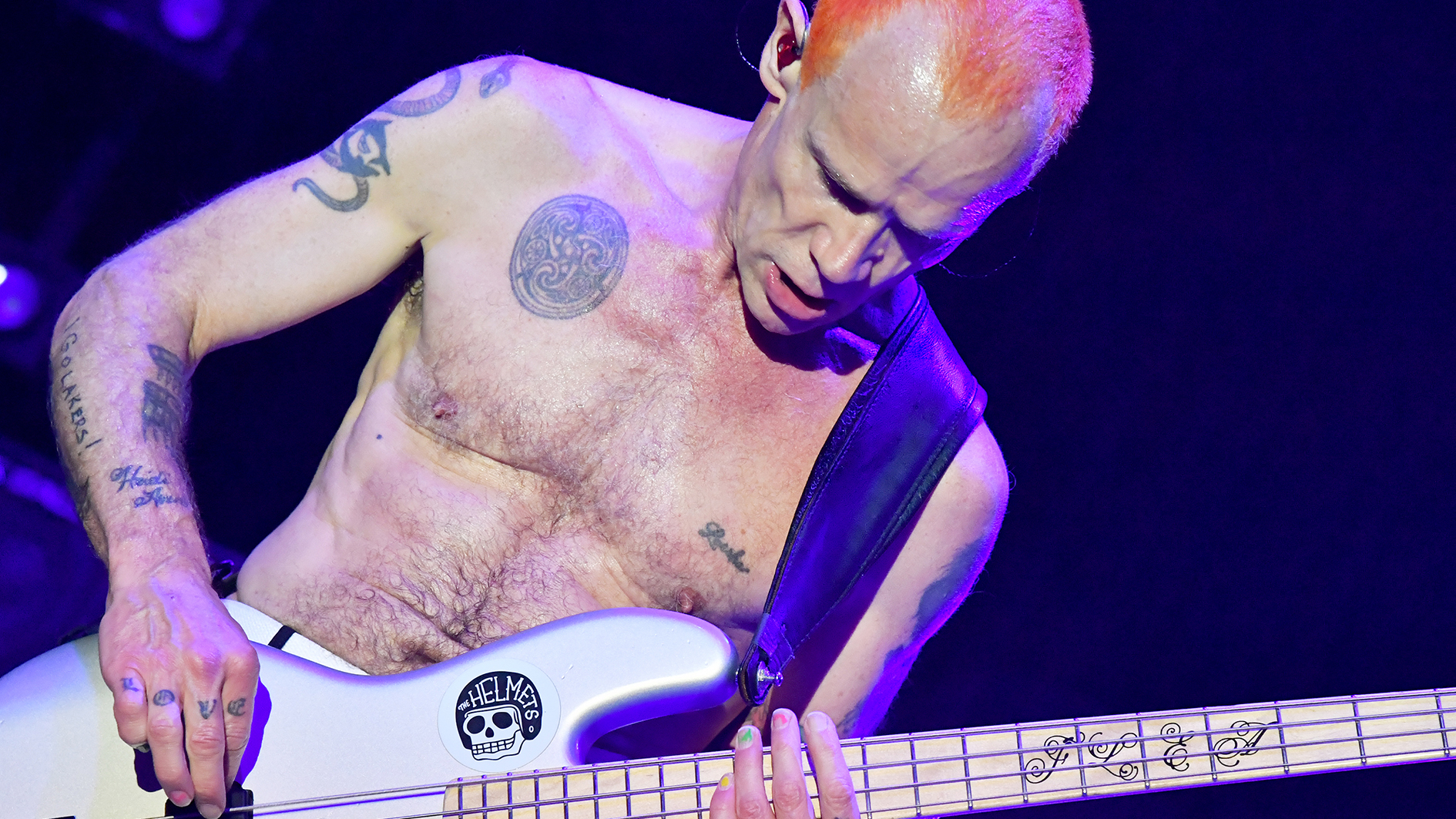

“Yes - any instrument is a magical thing, and I play a bunch of different instruments as well as bass, but through the years my relationship with bass just gets deeper and deeper, and I fall more in love with it.

"When I was a kid and I got my first bass, I would look at it, and see the way the strings floated above the neck, and I still do that. My one bass that I love the most - the ’61 Jazz that Fender copied for my signature bass - every time I look at it I’m amazed. It’s like looking at a great Picasso or an incredible thousand-year-old tree.

"Everything about it is perfect, it’s such a magical invention. When I was a kid I felt the same way about my trumpet, too.” The trumpet which, as he recalls in the book, that he threw in the air and which then came down and broke?

“Yeah, I know, it’s terrible!” he laughs. “I used to smash basses on stage too. I love ’em, but I smashed them to bits, wanting to be like Pete Townshend and Jimi Hendrix and Kurt Cobain. But I still think about basses the same way.

"You grab it, slide around on it and feel it with your hands; you slap, pull, thump, pluck and pop, and you get yourself into this hypnotic state, if you’re lucky, beyond thought, where you’re not thinking because you’re just a conduit for this rhythm, from wherever it comes from, from God to you and this instrument, through a cord and a speaker.

“There’s magic in there, and a lot of room for poetic interpretation. When I wrote, I tried to get underneath everything, whether it was doing drugs, playing music or basketball or anything that I did. I tried to say what it was really about. What are all these things for? I figured out that it’s all for love, you know. It was therapeutic to write this book, and a journey of self-discovery - in many, many ways.”

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.

![Red Hot Chili Peppers - Give It Away [Official Music Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/Mr_uHJPUlO8/maxresdefault.jpg)