How F*cked Up’s Mike Haliechuk wrote and recorded his guitar parts for the band’s new album in 24 hours – and why he gave up playing chords halfway through

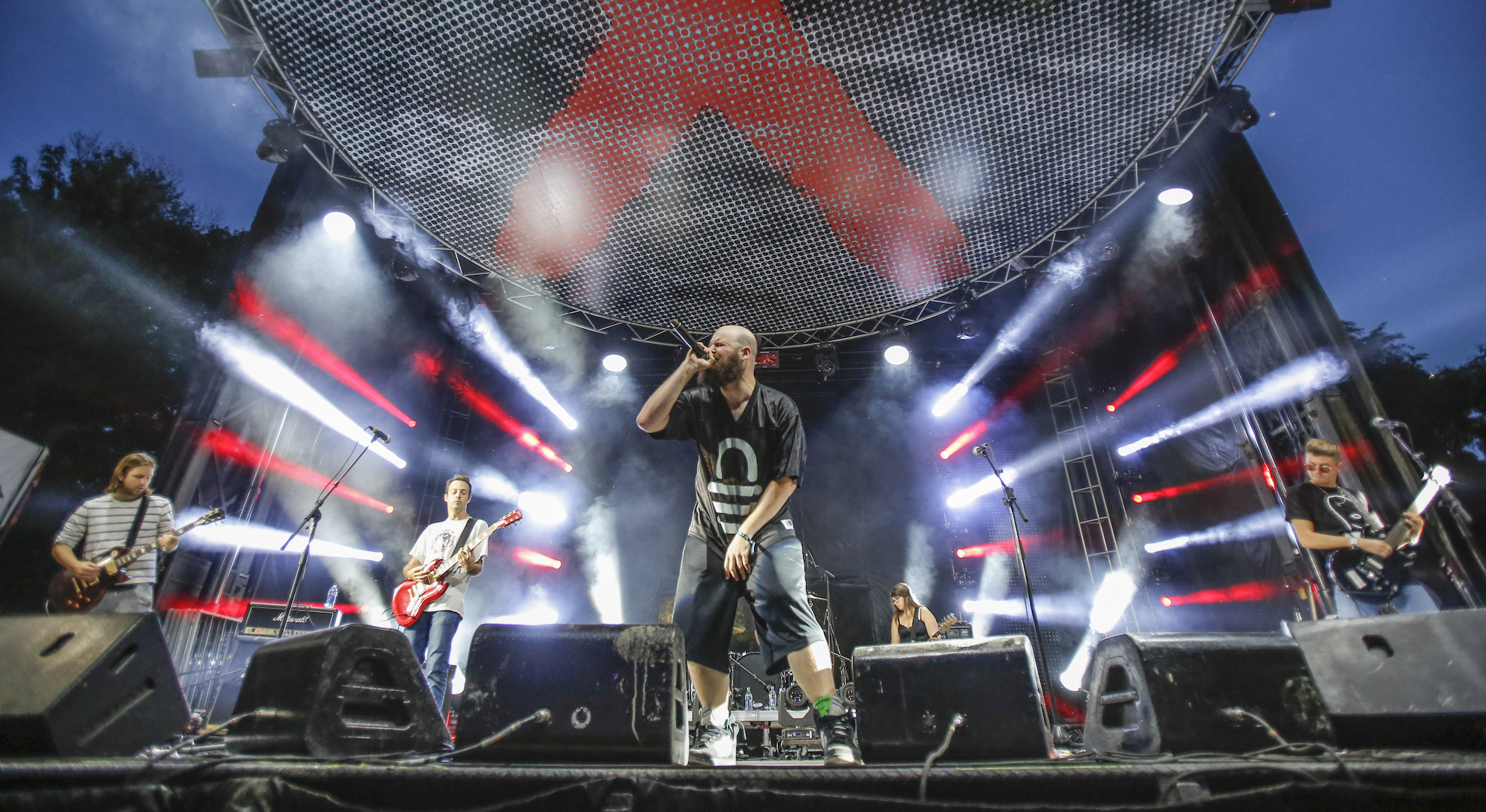

Ahead of their explosive new album, One Day, the ever-ambitious Canadian hardcore band's guitarist ruminates on his shrinking pedalboard, trusty Fender DeVilles, and eschewing chords in favor of "groovy one-note melodies"

One Day technically marks the first time Fucked Up’s Mike Haliechuk was able to write and record the guitar beds for an album in 24 hours. That’s not to say the founding guitarist and compositional mastermind for the experimental hardcore act hadn’t made the attempt in the past.

“Well, I try to write an album every single day of my life,” he tells Guitar World over Zoom, “but no – mostly I just sit around for three years [before I] get into the studio and do it all really quickly.”

Back at the tail end of 2019, Haliechuk went into Toronto’s Candle Recording Studio for a trio of eight-hour sessions with no set goal in mind, but eventually came up with a rich, ten-song amalgam of bruising punk spirit, high-gloss boogies, and treble-spangled heartland rock. Once he wrapped the guitar sessions, he passed the recordings around to his bandmates, who tracked their contributions under similar, time-restricted conditions.

Across a 20-year career, Fucked Up have explored a number of themes, whether that’s been threading the fictional character of David through several of their albums, or producing a series of EPs honoring the Chinese zodiac. On a sonic front, One Day’s thematic cohesion comes down to Haliechuk’s newfound love of an old Boss octave pedal, the guitarist’s punk hooks now mostly avoiding traditional chord work in favor of elaborately pitch-shifted, single-note layering.

“Halfway through recording, it was like, why am I even using guitar chords? They didn’t sound as heavy. That really affected the songwriting. I was writing songs based on all these groovy one-note melodies.”

Speaking with Guitar World, Haliechuk gets into time management, his ever-shrinking pedalboard, the unending appeal of beatdown hardcore, and more.

Writing and recording your guitar parts across 24 hours seems more modest in scope than most Fucked Up themes, but also more difficult in practice. First off, how did you hit on the conceit of One Day?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"It had taken ages to do the last two records [2014’s Glass Boys and 2018’s Dose Your Dreams], and I was getting bored with spending five years in the studio. It was just cutting the fat, and seeing what was underneath all the pretense of fucking around with tracks. It was an economical way of doing things, time-wise. It still ended up taking a long time [to finish the album] after recording had been done, but it was nice to have a new challenge."

When we’re talking 24 hours, were you locked in the studio for a literal full day while picking up the guitar, writing, finding a tone and all that?

"It was three sessions, around eight hours each. It was just me and an engineer. We came in and set up two Fender DeVilles and got a tone. Once we hit record, that’s when the writing started. I didn’t come in with any riffs, so the playing really was restricted to 24 hours. And then I didn’t pick up a guitar the rest of the [time], as we were mixing and arranging."

Had the DeVille already been your go-to amp?

"We know our way around the DeVilles, and they’ve been on most Fucked Up records over the past 10 years. We have four or five DeVilles that we use on tour, [and] in a session I’ll use two of those in a tiny room. I don’t consider tone so much, because so much of that comes in post. As long as it’s loud, and the amps are interacting with each other in a creamy way, I don’t get too fussy about finding the perfect tone."

What song started off the sessions?

"The first song [Found]. I was getting my hands warmed up with a B chord at the bottom of the neck, and I was moving my index finger up and down, like B to A. And that was the riff! I built it out from there. I think we had a song within 45 minutes."

Were you putting any other pieces of gear to work in the session?

"I used to be a bit of a gearhead – buying lots of pedals and trying out different sounds – but it’s gotten streamlined over the years. I don’t like having a big pedal setup on stage, and I don’t like having to carry a pedal box through the airport. Over the last five years I’ve whittled it down to a delay pedal and a wah pedal onstage, but more recently I’ve been taking the wah pedal out and replacing it with an octave pedal.

"This is the first record where I was really hitting that octave pedal. I was finding that I was [playing] less chords, [but] building chords with notes on the octave pedal.

"And then for my guitar, I have a Les Paul Studio that weighs a hundred pounds – I think it’s given me severe back problems. We use to have a lot of SGs, but their necks would break onstage or on airplanes, so now I just play this incredibly thick, sustaining Les Paul Studio."

Going back to the octave pedal, the record’s Roar is a great example of how you’re building out chords with layers of octaves.

"I don’t remember what it’s called – maybe counterpoint – but [I’m] assembling chords from individual lines. You can’t really play chords down low on the octave pedal. It sounds like garbage. But I’m so used to doing guitar overdubs anyways that I would come up with a riff and play it with one finger on one string, and then I’d do the same thing on the fifth. I’d be making up all these complex harmonies with [layers of single] guitar notes. So, a lot of the songwriting ended up being that."

What octave pedal were you using?

"It’s just whatever the Boss octave pedal is."

Getting into some of the music on the album, I Think I Might Be Weird is a fascinating piece. You play these jubilant, rising three-note guitar harmonies at the end of each line in the verses, and something about the way they vibrate has them sounding like Emotions-era Mariah Carey.

"Even before we knew how to write songs, we were good at coming up with these micro guitar licks. We weren’t making motifs or building songs, but we’d make up a little three note guitar thing – even our first 7-inch had a couple of those. We’d always base them on really simplistic things you can do on the high strings – Police [the band's 2003 single] is just based on this really easy-to-play couplet.

"I don’t know, that song sounds like the Damned to me: slightly baroque, but gritty punk. And then we were taking a minute to see where Jonah [Falco, the band's drummer] could plop on some vocals. Jonah has a really good falsetto."

With the time constraint in mind, were there any moments where a song was taking too long so you had to move on to the next track to keep pace?

"I didn’t come into it being like, 'I need to produce a whole record.' It was more, 'let me see what I can do.' I didn’t have a goal that I could stray from; it was an open thing. I think we ended up with 16 completed songs. There’s a 10-song record, a bunch of B-sides, and a couple songs that weren’t good enough to use."

There’s a different kind of brightness to the guitars on Cicada, the song you’re singing lead on. What do you remember about making this one?

"I was definitely going for a different vibe on that song. It sticks out: it’s all chords; it’s at a slower pace, a different kind of urgency. I wanted it to be more somber – you know, the song is about losing your friends. I didn’t want to treat that song as part of this sonic experiment. I didn’t want people to listen to that and be like, ‘Oh, this is part of some hokey trick that Fucked Up did.’ I wanted it to be a song on its own, which served a different purpose."

Do you worry that people think that Fucked Up are just doing some hokey trick, or that each record is the band moving onto the next gimmick?

"I don’t worry about it, but I know that’s a thing. It’s just part of being in this band.

"It’s not like we sit around at a table and come up with gimmicky records. It’s like an OCD thing, needing to file away my artistic expression in these patterns, or 12-record series [the band's long-running Chinese zodiac 12" series]. Art [can] come out of people in a strange way."

Late last year, you also released the Oberon EP, a much darker record than One Day. How long did that one take to make?

"That was during the first break in the pandemic [where] you could go and do stuff again. I booked the same place in Toronto, Candle Recording Studio, for two or three days and, again, I didn’t have any ideas. I came up with 15 terrible demos, and those three or four songs [on Oberon] are what were usable. It took a while to craft them into songs.

"It’s not that it’s jokey, but that’s an unserious record – just because of how over-the-top serious it's purporting to be. Thematically, I just wanted these to be re-conceived fairy tales; me and Jonah and Damian [Abraham, the band's vocalist] each wrote about a mythological character for a song; there’s a zombie-looking guy on the cover. That’s a funnier record, for me, than One Day."

If you fell in love with the octave pedal while making One Day, was there a similar experience while making Oberon? There’s a pretty specific fuzz streaming through these four songs, for instance…

"I think it was the exact same setup. It’s just that the songwriting is more menacing, and there are some more aggressive synths on it. Guitar-wise, it’s the same. Two Fenders. Same room. Same pedals. Just a different intention: to make it sound evil."

It’s arguably the heaviest Fucked Up record, working with a darker kind of hardcore than you have in the past.

"When I was getting into punk as a teenager, that’s what a lot of hardcore bands sounded like. Me and Damian were getting into what is often referred to as beatdown hardcore – bands like Hatebreed.

"That was a gateway to heavier music with a little more nuance. We would get the Victory Records sampler, which had stuff like Integrity and Bloodlet – suburban music that was extremely evil and heavy-sounding. And then you get into stuff like His Hero Is Gone, Crossed Out, or Copout, or Neurosis. Stuff that’s truly weird and menacing. Like there’s this band Kiss It Goodbye, and I’d listen to their record five times a day, just on a tape. That’s the stuff I loved when I was a kid."

Is there space in a Fucked Up set to go back and forth between a gloomy song like Oberon and those happier pieces like I Think I Might Be Weird?

"I mean, you can make anything work together [laughs]. In the summer we played Strix [off Oberon] into David Comes to Life [off 2006’s Hidden World]. We did that all summer. Oberon is heavy and slow, but Strix is weirder. It’s really manic."

It’s been almost three years, now, since you jumped into the studio to record your parts for One Day. Where are you at with writing newer Fucked Up songs at the moment? Has that session galvanized you towards making music much more quickly?

"I counted it out the other day, and I have nine or ten sides [of music] that are at various stages of [completion]. Various projects, but mostly for Fucked Up. They’re kicking around slowly."

- Fucked Up's One Day is available for preorder now via Merge Records.

Gregory Adams is a Vancouver-based arts reporter. From metal legends to emerging pop icons to the best of the basement circuit, he’s interviewed musicians across countless genres for nearly two decades, most recently with Guitar World, Bass Player, Revolver, and more – as well as through his independent newsletter, Gut Feeling. This all still blows his mind. He’s a guitar player, generally bouncing hardcore riffs off his ’52 Tele reissue and a dinged-up SG.

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)