“I was watching my best friend get eaten alive by heroin. It was amazing how far gone he was, physically, but he was still able to play the shows”: Failure’s Ken Andrews looks back on the fraught creation of 1996 cosmic epic, Fantastic Planet

Fantastic Planet was recorded at a time when substance abuse was tearing them apart and their record label folded. Now Andrews can look back with a bit of perspective on an artistic triumph that's given them a second life

Los Angeles trio Failure were coming off a buzz-building global tour with longtime friends Tool when they set out to make their ambitious, career-defining Fantastic Planet in the mid-Nineties.

But after playing the biggest shows of their career up to that point, guitarists/bassists Ken Andrews and Greg Edwards and drummer Kellii Scott escaped to metal god Lita Ford’s home in Tujunga, California to track their third full-length. The results were otherworldly.

The ecosystem of their 17-song Fantastic Planet is alive with neon lilac, alt-gloom-gaze (Heliotropic); high-drama chord pivots (Pitiful); and distorted tones seemingly conjured from a most melancholy jet engine (Stuck On You).

Reflecting different rhythmic philosophies, Edward affixed an elegant elasticity to his standup bass sections, while Andrews anchored into steady low-end bass chording amid the hypnotic lock groove of Another Space Song.

While partly inspired by 1973 French sci-fi film Fantastic Planet, Edwards’ lyrical contributions reflected the alienation of a burgeoning heroin addiction. He navigated drug busts and police intimidation (Sergeant Politeness; its most enduring number, The Nurse Who Loved Me, is a tragically beautiful, phaser-stunned glam ballad where a health worker is praised for handing the narrator the “pharmacy keys.” Romantic, in a messed-up kind of way.)

Andrews considered their wide-scope celestial odyssey “the best record we had made so far,” but when their label folded, Fantastic Planet got put in limbo for 18 months. It was depressing, but Andrews, Edwards and then-Tool bassist Paul D’Amour distracted themselves at Ford’s house by subverting new wave hits as the Replicants.

When Warner Bros. picked up Fantastic Planet in the summer of ’96, Failure enlisted future Queens of the Stone Age guitarist Troy Van Leeuwen to fill out the live sound, though interpersonal struggles imploded the quartet within a year.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The whole purpose of buying the gear and renting a cheap house was to remove the time restrictions and allow us to essentially write in the studio

That said, the mythos of Failure skyrocketed in the ’00s through file-sharing and big-boost covers from A Perfect Circle (Van Leeuwen co-founded that band; Edwards was a touring member in 2018) and Paramore. And after working apart for the bulk of two decades, Edwards, Andrews and Scott reunited in 2014, having since delivered another three albums’ worth of pensive, personal space rock.

While taking a break from self-producing a full-length documentary on the history of the band, due sometime in 2025, Andrews tells Guitar World how being left to their own devices – and vices – led Failure to explore the outer reaches of their Fantastic Planet.

How did you end up renting Lita Ford’s house?

“One of Failure’s peers was this band Medicine. I think I saw [guitarist/vocalist] Brad Laner at a party in L.A., told him that we'd just gotten the thumbs up from Slash to self-produce this third record, and that they gave us money to buy our own gear to record it. We were looking for a space to rent, and he was like, ‘That’s pretty funny, because I just rented this little house up in Tujunga for a month, and we finished a new Medicine record up there.’

It wasn’t a luxury home. The foundation had been cracked in the ’94 Northridge earthquake. [Lita] wasn’t living there. This was her three-bedroom starter house that she bought with the first money that she made in the music business. She couldn’t sell it, so she was looking for anyone to rent it. We moved in a week after Medicine moved out. We were there six months with Failure, and then another three months making the Replicants album.”

What did you like about the setup there?

“We were renting it for $2,000 a month; that’s what a regular recording studio in L.A. cost per day. The whole purpose of buying the gear and renting a cheap house was to remove the time restrictions and allow us to essentially write in the studio.”

The most significant guitar purchase before we moved into the Fantastic Planet house was a 1976 Les Paul Standard that I bought on Sunset at a great vintage shop

You mentioned buying recording equipment before moving into the house, but did you level up your guitar gear?

“We definitely got a few new guitars. I don’t know what happened to the main guitar that I had used on the first two records [1992’s Comfort and 1994’s Magnified], whether it was lost or stolen, but it had a unique sound. I’d built that out of mail-order parts from Warmoth.

“It was a Strat-style body and neck, but it had a humbucker in the bridge position and a single-coil in the neck, like a Van Halen-type thing. The [humbucker] was a Bill Lawrence. That’s not super high gain, but it’s teetering on it. Every time I hear old demos or the first two records, I just hear that pickup. The fact that I don’t have it anymore bums me out.

“The most significant guitar purchase before we moved into the Fantastic Planet house was a 1976 Les Paul Standard that I bought on Sunset at a great vintage shop. That guitar paid [itself] off; it’s a staple of the band still. But there’s a lot of single-coil on Fantastic Planet, too. That’s either done with a Jazzmaster or a Tele.”

Rig-wise, what’s on this record?

“My live rig at that point was a rack system that [Bob] Bradshaw had wired. It was a Marshall JMP midi preamp – the gold one – going into a Rocktron Intellifex multi-effects unit.

“A lot of times the Intellifex would also feed into a huge rackmount VHT stereo tube power amp, and then into two Marshall 4x12’s. And then I would have a Fender Twin on top of one of the Marshalls that I would lean on for clean sounds.

“I also had a mega-crunch sound [while using] a Big Muff going to the Twin. The Big Muff and the Twin, together, is very scooped. Combining that with the Marshall was a big part of Fantastic Planet’s power chord sounds.”

You and Greg are often switching off bass and guitar duties. Can you pinpoint the differences between your styles on either instrument?

“He’s a way more sophisticated bass player than I am. I play bass like a rhythm guitarist; I play a lot of chords. If there’s a bass run or a sophisticated passing riff, I usually don’t do that. With guitar, though, both of us really like weird, dissonant riffs and ambient things.”

I handed Greg the guitar and hit record... That was his first take, stream of consciousness. Probably half the notes aren’t in key, but I think it’s a brilliant solo. I play it live now

Ken Andrews on The Nurse Who Loved Me

There’s bittersweet glam grandeur to The Nurse Who Loved Me. Where did that come from?

“Greg had a very unusual cassette demo of that before we got to the house. You could hear an acoustic guitar playing chords, and Greg was singing something, but it was shrouded in all these weird sound effects. I couldn’t tell if there was an actual song playing [at first], but by the time I got to the end of it, I was like, ‘Holy shit, this is amazing.’

“I suggested making it more of a piano song than a guitar song – we had just found Lita’s digital piano, a Korg she had left under a bed. Greg has great rhythmic feel on keyboards, so ultimately, we ended up recording the basic tracking with just Kellii playing drums and Greg playing piano. We didn’t use a metronome on that song. We really wanted it to ebb and flow with the chord changes, and have some really specific retards in spots.

“That’s Greg’s guitar solo on the record. I was playing the rhythm guitars on the song, but then [I thought I’d] take a crack at doing a solo. I tried for a half-hour, but didn’t like anything I was coming up with. It was too sentimental, so I handed Greg the guitar and hit record. I don’t even know if he had played guitar that day. That was his first take, stream of consciousness. Probably half the notes aren’t in key, but I think it’s a brilliant solo. I play it live now.”

Dirty Blue Balloons features another solo that’s working in and out of key.

“I did that one! You’d probably think that the person who played the Nurse solo also played the Dirty Blue Balloons solo, but they’re not the same person. They have the same ethos, though. A record I was listening to where I really love the solos is David Bowie’s Scary Monsters, with Robert Fripp and Carlos Alomar.

“Their solos on that record are so art-school; very anti-solo. They don’t rely on the blues scale. They’re experimental; they’re breaking a lot of rules. Those were the kinds of solos I was interested in at the time.”

Band members started struggling with addiction through the making of Fantastic Planet. How aware were you of that at the time?

“Greg’s heroin usage was climbing, [but] it was still the honeymoon period for him. Whether it was breaking down his inhibitions in terms of writing and/or exploring himself as the subject of the lyrics, I don’t know… I was starting to get worried, but at the same time he was coming up with some really good material. His contributions were just amazing to me.

“When [Failure] started [using heroin], we were all doing it together. There was a certain amount of safety in that, in terms of people not doing it too much. But then Kellii and I both noticed that he started using with other people, and that’s when we started to get really concerned. So, there was that darkness for sure.”

“And then about five months into making the record, our manager calls and says, ‘I know you guys are almost about to finish up there, but I’ve got some bad news. Slash Records are trying to sell the label… It’s quite possible that when the label is sold, whoever buys it will be under no contractual obligation for this to come out.’ That sent me into a very deep depression.

“The songs that weren’t finished at that point were the last two songs on the album, Heliotropic and Daylight. In a way, they’re the two darkest songs on the record. When I hear Daylight, I hear despair and sorrow. I’ve been [re-evaluating] the lyrics I wrote for that song, and the underpinning there is that we’re realizing that this [album] might never see daylight. I think Heliotropic was Greg admitting, ‘Yeah, I’m an addict. If I wasn’t at the beginning of the record, I am now.’”

When Fantastic Planet eventually came out through Warner, you started touring as a quartet. How did Troy Van Leeuwen end up playing guitar in Failure?

“I became extremely convinced that in order to support Fantastic Planet properly, we needed a second guitarist. I was looking at the sound of the album, and realizing how many times there were two very distinct guitar parts happening at the same time, not just one [rhythm guitar] playing chords that the bass was already covering.

“Everyone else who had heard the record was right there with me. Kellii is the person in Failure who knows all the musicians in L.A., and he had already been playing in one or two different projects with Troy, so we became friends. At some point we were like, 'Yeah, this is the guy we should take on the road with us.'”

What kind of energy did he bring to the songs?

“There’s a certain heaviness and girth that you can achieve with two guitar players if they’re both playing power chords. We didn’t have Fractals then, so creating really thick sounds live was hard.

“That part of it was really cool. I’ve been looking back at the very few old shows that we have on video from ’96 and ’97, and I can hear that he was definitely a better guitar player than I was.

“He would introduce alternate versions of riffs or melodic lines that were very static on the record – like the same figure looping every four bars. He’d turn an instrumental section into a pseudo guitar solo moment.”

How do you remember this first phase of Failure winding down?

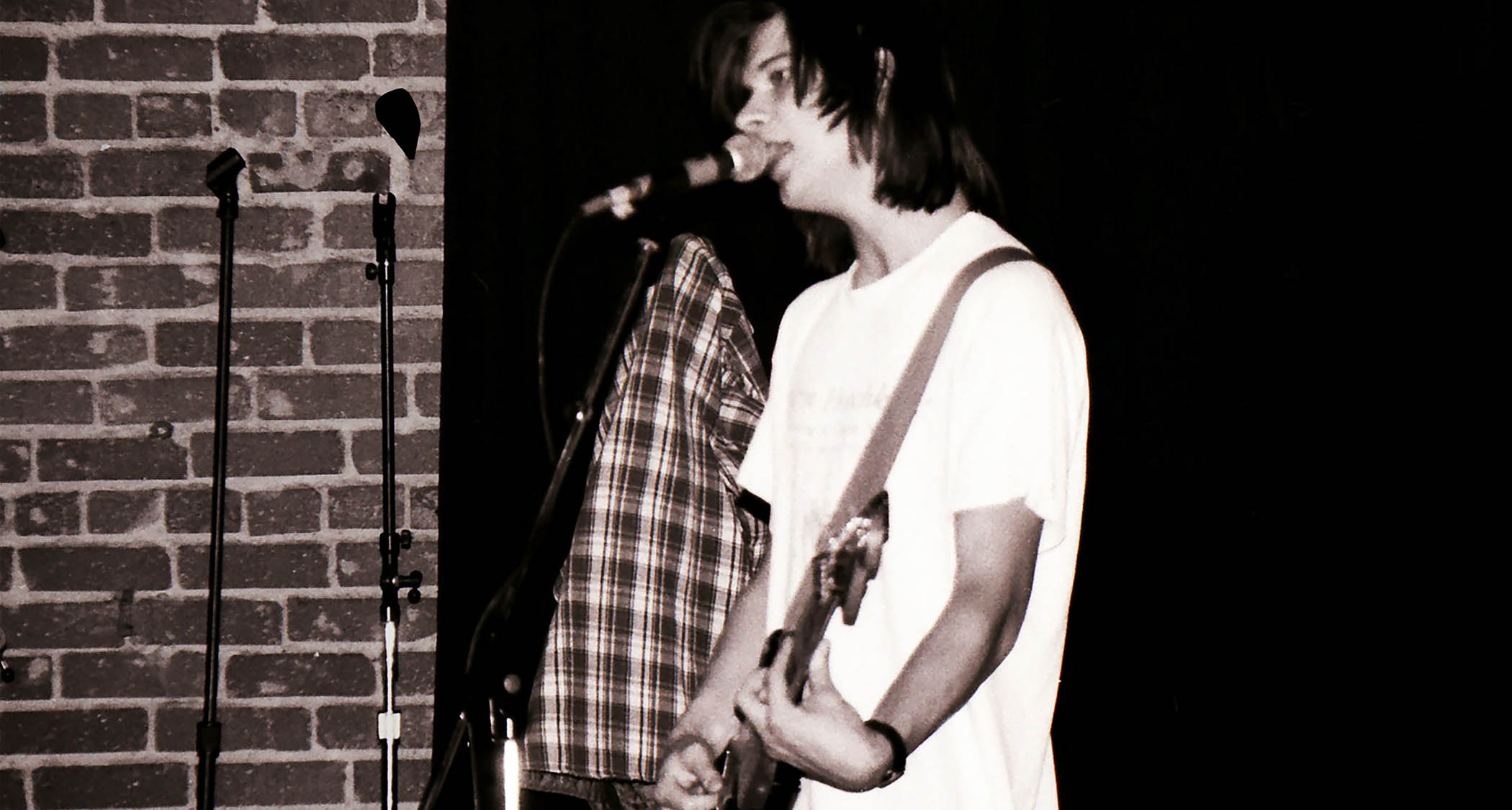

“We did three or four tours that last year where we were supporting Fantastic Planet, and we ended the cycle with Lollapalooza ’97. The last show we played was in San Francisco. That entire [tour cycle] was heartbreaking, because I was just watching my best friend get eaten alive by heroin.

There were a couple times where Greg was really focused on what he was playing but lost focus of his own balance.

“It was amazing to me how far gone he was, physically, but that he was still able to play the shows. Musically, there weren’t that many times where the drugs were fucking him up, in terms of playing the wrong notes.

“There were a couple times where he was really focused on what he was playing but lost focus of his own balance. I remember a couple of our crew guys running out and pulling him back from falling off the stage. It was not a fun time.”

You’ve been in this prolific reunion phase for the past decade. Set against the newer material, what is the legacy of Fantastic Planet to the members of Failure?

“I definitely look at it as two halves of a career – we had our Nineties career, and we have our career now – but Fantastic Planet is the album that actually brought us back, if you think about it. Newer fans found it after we broke up, through file-sharing and CD burning in the aughts.

We kept hearing all these rumors that Failure is more beloved now than in the '90s...At some point we were like, ‘Let’s see if these rumors are true’

“We kept hearing all these rumors that Failure is more beloved now than in the Nineties. Then we started hanging out and enjoying each other’s company again. We had kids; drugs were out of the picture. At some point we were like, ‘Let’s see if these rumors are true,’ so in 2014 we booked a show at the El Rey in Los Angeles, and it sold out in less than five minutes. That had never happened in the Nineties.

“It’s kind of a cool story in that we can have our own little world and be completely understood and appreciated in a way that we never were in the Nineties. We were always being compared to grunge bands. We had some of that in our sound, but we were something else. The full understanding of the band didn’t happen until after we broke up.”

Gregory Adams is a Vancouver-based arts reporter. From metal legends to emerging pop icons to the best of the basement circuit, he’s interviewed musicians across countless genres for nearly two decades, most recently with Guitar World, Bass Player, Revolver, and more – as well as through his independent newsletter, Gut Feeling. This all still blows his mind. He’s a guitar player, generally bouncing hardcore riffs off his ’52 Tele reissue and a dinged-up SG.

![Failure - Fantastic Planet (Outtakes & Demos) [1995] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/eQbUBeQEBIw/maxresdefault.jpg)