Everything guitar players need to know about reverb, from the history of the effect to how to get the best from your pedals

Long before digital simulations – including reverb pedals – became sophisticated enough to blur the lines between actual and artificial ambience, studio engineers and electric guitarists were obliged to use springs, specially built chambers and plates.

The reverb characteristics these devices produced may have had technical shortcomings, but the characteristics were often so strong and sonically pleasing that they became integral to the sound of recorded music in the post-war era.

Room-inations

The terms echo and reverb were once used interchangeably. By and large, we associate echo with shouting a word into a large reflective space and hearing our voice bounce back at us multiple times, a second or so later.

Reverb is created by multiple soundwaves bouncing off hard surfaces, so ‘echo’ isn’t entirely incorrect. However, the reflections are so close together that they create continuous sound that gradually dies away. When the time-lapse between the initial sound and the reflected sound is sufficient for both to be heard separately and distinctly, the accepted term is ‘delay’.

Reverberant spaces tend to be those with hard surfaces that reflect soundwaves. You will have noticed how a bathroom with a tiled floor and walls sounds very different to a carpeted living room with lots of soft furnishings. If you haven’t, then grab an acoustic guitar and try playing in both. Similarly, stairwells, churches, sports halls and cathedrals tend to be reverberant.

When designing concert halls, recording studios or public spaces, acoustic engineers consider the RT60. This is the amount of time it takes for the level to drop by 60dB, and it can be manipulated and controlled to optimise the acoustic environment for any specific purpose.

In a lecture hall or a talk-radio studio, speech intelligibility is paramount and reverb is best kept to a minimum. But if you’re singing or playing a musical instrument, a bone-dry acoustic is uninspiring and unhelpful. This is why concert halls and venues generally retain some degree of ambience.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But recording a large number of musicians simultaneously in a single room is one of the great challenges of studio work. If the room is very reverberant it becomes even harder to achieve clarity, separation and a coherent stereo image because the microphones will be detecting reflected sound along with the direct sound.

Also, if you record natural room reverb, you’re stuck with it. This is why recording studios tend to have carefully controlled acoustics, and many engineers prefer to eliminate room ambience when recording and add reverb effects later in the mix.

Those of us who use computer-based DAW recording systems and effects pedals will also be aware of the range of reverb presets on offer. They are largely named after the old-school analogue devices upon which they’re based, so let’s take a look at some common types to learn more about their background and tonal characteristics.

Chambers

Long before electronic effects, studio designers found a way to add reverb by using ambient spaces that were acoustically isolated from the main recording area. In its simplest form, a speaker and a microphone could be set up in an echoey room and individual instruments could be routed out through the speaker, and the microphone signal could be returned to the mix.

More sophisticated versions of this setup would have two speakers and a pair of carefully placed microphones for stereo reverb. These spaces enabled mixing engineers to balance the amount of reverb in a very precise way, and this send and return principle remains the same with modern digital reverbs and plugins.

Back in 1947, Universal Audio founder Bill Putnam is credited with the first use of a reverb chamber, and it was the studio’s bathroom

These rooms became known as reverb chambers and were often carefully designed and tuned in order to refine the ambience. Back in 1947, Universal Audio founder Bill Putnam is credited with the first use of a reverb chamber, and it was the studio’s bathroom.

Other studios would follow suit during the 1950s and some, like Abbey Road and Capitol, became famous for their chambers. Producers would often book chamber-equipped studios specifically for their unique sounds. And if you have an echoey bathroom, a spare speaker and a microphone, you can try this at home.

Alternatively, check out the numerous chamber plug-ins that are available for DAWs. Many of them are modelled on those world-famous chambers and live rooms that still survive.

Getting tanked

Many of us will be familiar with spring reverb because it’s the type that was used in guitar amps before onboard digital reverb became viable. Most vintage reissues and boutique tube amps still come with springs attached. A patent for a spring reverb device was granted to Laurens Hammond in 1939, and in 1961 Alan Young, an engineer at Hammond, designed a smaller spring reverb tank.

Although amp reverb cannot be described as high fidelity, it shaped the sound of 60s instrumental groups, surf music and Spaghetti Western soundtracks

Onboard reverb soon began appearing in Gibson and Danelectro guitar amps, and the Ampeg Reverberocket is renowned for its reverb. Fender was slower on the uptake and initially developed a standalone reverb unit called the 6G15. The first Fender amp with reverb was the brown Vibroverb in 1963 and much of the Fender reverb sound comes from having the send post-tonestack. This scoops the midrange and emphasises those splashy treble frequencies.

Although amp reverb cannot be described as high fidelity, it shaped the sound of 60s instrumental groups, surf music and Spaghetti Western soundtracks. Some players, such as Freddie King, Roy Buchanan and Mike Bloomfield, would max out the reverb on their Fender amps.

Studio springs

Not all spring reverbs are lo-fi devices and some are capable of smooth and sumptuous stereo reverb. AKG made some fantastic units, notably the BX15 and refrigerator-sized BX20, and it’s a sound heard on countless classic recordings. Schaller and Grampian also manufactured spring reverbs, and in recent years the Bandive Great British Spring has proved popular.

Some find spring reverbs a bit splashy for percussive instruments, but they can sound amazing on vocals, brass, strings and, of course, guitar.

Smashing plates

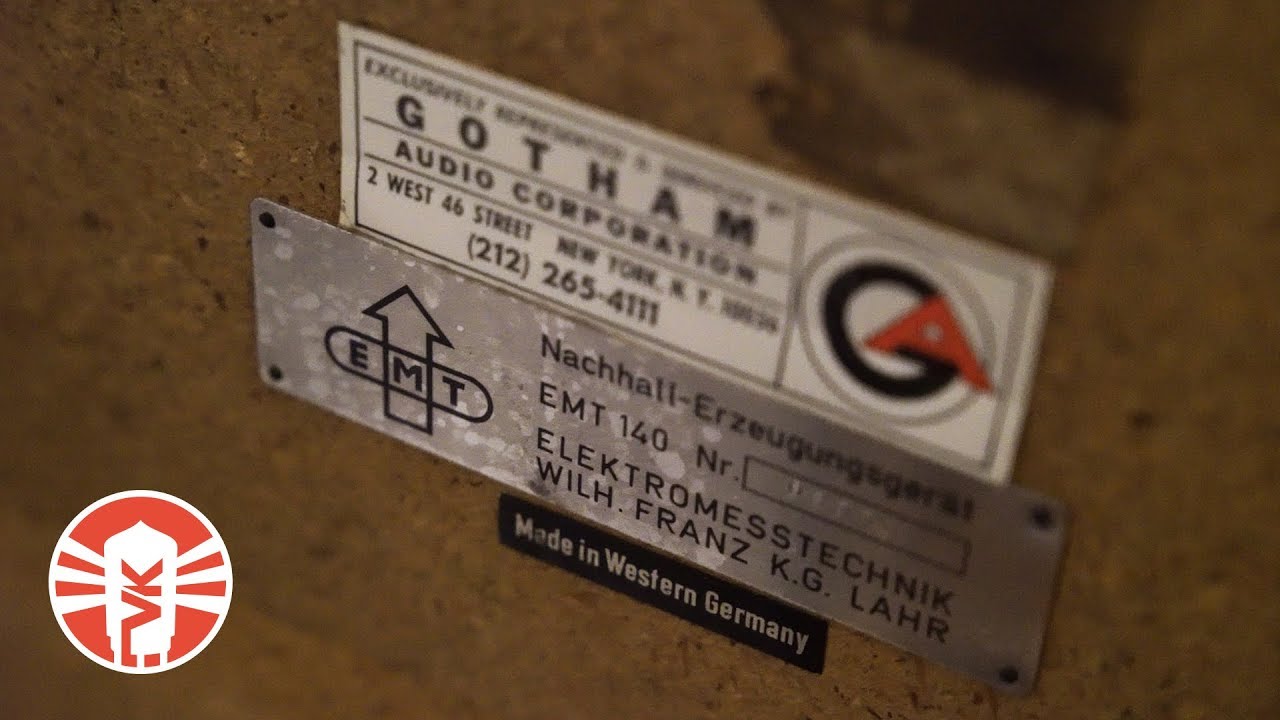

In 1957, a German company called EMT (Elektromesstechnik) released the EMT 140 Reverberation Unit. A small speaker‑like motor would set a large metal plate into motion and a contact microphone sensed the vibrations and returned the signal to the mixer. The plate was carefully tensioned within a frame, and for stereo plates two contact microphones were deployed.

Reverb time could be adjusted using dampening pads and EMT made a special remote controller. The reverb tone could be optimised using equalisation on the input channels and pre-delay could be added by running the auxiliary send through a tape delay or a digital delay set to a single repeat.

The first EMT plates had valve amplifier circuitry, but this later changed to transistor-based solid-state. Original EMT plates remained the industry standard until the 1980s and they are still the go-to analogue reverb for many mixers and producers as the reverb tone is huge, lush, smooth and dense. The main difficulty with using EMTs is resisting the temptation to put everything through them.

They are also huge and heavy, which is why EMTs are largely confined to high-end professional studios these days. The EMT 144 was the world’s first digital reverb when introduced in 1972 and it was followed by the 250 (aka The Dalek) in 1976. Fortunately, most DAWs and studio plug-in companies offer plate simulations and they can be extremely convincing.

Rack reverbs

Although the technology might be regarded as primitive, some early digital reverbs have acquired legendary status. Typically seen in studio effects racks, some classics include the Ursa Major Space Station and Lexicon’s 224, 448 and PCM models. The AMS RMX-16 was a staple of ’80s mixing and its non-linear preset was almost ubiquitous on those exploding snare drums.

More commonly used by guitarists and lower-end studios, units like the Yamaha SPX90 and the MidiVerb and QuadraVerb by Alesis were multi-effects units. They all contained numerous reverb presets as well as delays and modulations.

These are the devices to hunt down if you’re into processed ’80s pop and authentic shoegazer guitar tones. But for practical purposes, rackmount effects have largely been rendered obsolete by studio plugins and DSP stompboxes.

Bit boxes

It’s curious that so much cutting-edge technology has been devoted to recreating effects from the past, but we’re not complaining, of course. Some reverb pedals are modelled after specific devices, such as Catalinbread’s Fender 6G15-emulating Topanga and Yamaha FX500-soundalike Soft Focus Reverb.

Others, including the Strymon BigSky and Night Sky, Boss RV-500 and Eventide Space combine multiple studio-quality presets with front‑panel controllability, MIDI in/out and USB connectivity.

If you must have real springs, there are various pedal/spring combinations with tanks that are built into the box or will stash under your pedalboard. Check out the Anasounds Element, Carl Martin HeadRoom, Demeter RRP-1 Reverbulator, VanAmps Reverbamate Sole-Mate and SurfyBear Reverb.

As for standalone valve reverbs, Fender no longer makes the 6G15 reissue, but you can check out Dr Z’s Z-Verb and the Victoria Reverberato.

User tips

The amount of reverb you use is a matter of taste, but for styles like surf and rockabilly it’s almost mandatory. If you’re playing fast and heavy music that depends on precision and tightness, you should probably avoid reverb altogether. When playing live, try to gauge the amount of room ambience and set your reverb accordingly. If it’s an echoey room, you may need to dial it down.

Onboard spring reverb has a specific sound and we may consider it integral to our tone. In recording scenarios, studio engineers will often ask us to kill the reverb so they can add some later in the mix. It won’t sound the same so you may need to stand your ground – but also be prepared to compromise. Studio reverb can sound just as good or even better than spring reverb, and a bit of both often works.

Huw started out in recording studios, working as a sound engineer and producer for David Bowie, Primal Scream, Ian Dury, Fad Gadget, My Bloody Valentine, Cardinal Black and many others. His book, Recording Guitar & Bass, was published in 2002 and a freelance career in journalism soon followed. He has written reviews, interviews, workshop and technical articles for Guitarist, Guitar Magazine, Guitar Player, Acoustic Magazine, Guitar Buyer and Music Tech. He has also contributed to several books, including The Tube Amp Book by Aspen Pittman. Huw builds and maintains guitars and amplifiers for clients, and specializes in vintage restoration. He provides consultancy services for equipment manufacturers and can, occasionally, be lured back into the studio.

“The original Jordan Boss Tone was probably used by four out of five garage bands in the late ’60s”: Unpacking the gnarly magic of the Jordan Boss Tone – an actual guitar plug-in that delivers Dan Auerbach-approved fuzz

“This is a powerhouse of a stompbox that manages to keep things simple while offering endless inspiration”: Strymon EC-1 Single Head dTape Echo pedal review