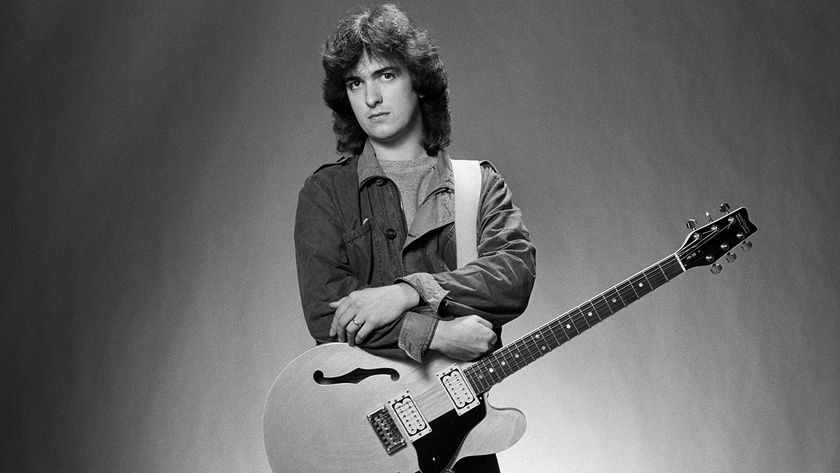

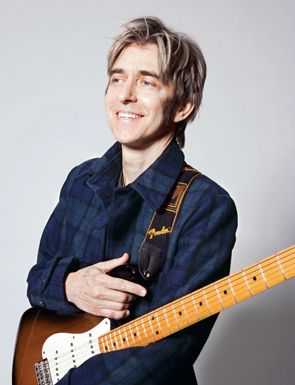

Eric Johnson On His Most Revealing Album: 'Up Close'

Originally published in Guitar World, February 2011

He’s famous for his perfectionism, but Eric Johnson presents the most spontaneous and revealing music of his career on his latest album, Up Close. The Austin powerhouse talks about loosening up, discovering his signature tone and performing on the latest Experience Hendrix tour.

Contrary to popular belief, Eric Johnson does watch the clock. The venerated guitarist, known for his leisurely pace in the studio, is sitting in the conference room of the Guitar World offices, digging into a bowl of soup and wolfing down a sandwich. In just under 90 minutes he’s expected uptown at New York City’s Beacon Theatre, where he’s appearing with other six-string notables in the latest edition of the Experience Hendrix tour. Time is tight, but Johnson nonetheless provides thoughtful and unhurried explanations on a variety of topics. Chief among them is his reputation as a perfectionist. The guitarist is acutely aware of the issue, and in a soft, easygoing Texas drawl says, “The truth is, it kind of bothers me. I mean, let’s be honest, the term ‘perfectionist’ is usually said with this negative connotation. Part of me understands why people attach that word to me. But on the other hand, I listen to some of my favorite artists, people like Stevie Wonder and Hendrix and so many others, and I’d be willing to bet—no, I’m sure—that they all aimed pretty high when they did their best work. Not that I’m putting myself on their level, but I do set the bar high with what I do. If you want to shoot for the moon, you shoot for the moon. The end justifies the means.”

He thinks for a second, swallows a mouthful of soup, and adds, “Well, I guess you can take things a little too far, and I could plead guilty to that. But I’m getting better. This new album didn’t take nearly as long as my others ones.”

True and not true. Although Johnson claims to have “gone more with the flow and allowed things to happen naturally” while recording his new CD, Up Close, it comes a full five years after his last disc, 2005’s Bloom, which is pretty much par for the course where his recordings are concerned. In all, he has issued only five studio albums since he debuted 32 years ago with 1978’s Seven Worlds, not counting 2002’s Souvenir, a collection of cuts recorded over the preceding 25 years.

Universally praised by peers and fans as one of the few musicians to achieve that rarity in music—a signature sound and style—Johnson has won a boatload of “greatest guitarist” and other such awards, including a Grammy for the jubilant, radio-friendly “Cliffs of Dover” (from 1990’s Platinum-plus Ah Via Musicom). That famed “Eric Johnson sound”—a unique combination of clean and dirty tones coupled with a piercing yet joyous violin-like finger vibrato—is very much in evidence on Up Close’s 15 mesmerizing tracks. It was recorded in Johnson’s hometown of Austin with his longtime engineer and co-producer, Richard Mullen, along with the tight core of musicians he’s worked with over the years (C. Roscoe Beck on bass, drummers Tommy Taylor and Barry “Frosty” Smith, and keyboardist Red Young). The album is almost an even split of vocal songs (Johnson sings three of them) and instrumentals, and it features appearances by guitar masters Sonny Landreth and fellow Austinite Jimmie Vaughan, along with vocals by Jonny Lang, Malford Milligan and the Joker himself, Steve Miller.

Johnson, Miller and Vaughan tear it up in true Lone Star fashion on a raucous cover of the Electric Flag song “Texas.” But the heart and soul of Up Close can be heard in Johnson’s original compositions. They are among his most deeply personal to date, inspired by self-reflection, epiphanies and affection for friends and family members. There’s the brisk yet moody pop rocker “Brilliant Room,” on which Austin blues veteran Milligan turns in a sparkling, soulful performance. Then there’s the shimmering, twinkling “Gem,” an ameliorating ride into the subconscious which is bound to join the ranks of Johnson’s pantheon of instrumental masterpieces. On the gutsy, blues rock stomper “Austin,” the guitarist fills the verses with glassy, jazzy chords before letting loose with a jaw dropper of a solo in which notes seemingly summersault over one another.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I really love that song,” Johnson says. “I’m a born-and-bred Texan, and I wanted to write something about the town I remember as a kid. Austin’s still a great place to live, but it’s changed in some ways environmentally that I’m not pleased about.”

And for sheer cosmic guitar wizardry, there’s a trio of daring musical soundscapes—“Awaken,” “Traverse” and “The Sea and the Mountain”—originally cut as one continuous number but later sectioned into three separate pieces. “Even with something like those musical interludes, the idea was to expose myself as an artist more than I ever have before,” Johnson says. “See, in the past, I would’ve labored over that piece—well, they’re pieces now—but this time I just went for it. It was a lot of fun, especially when I went nuts with the feedback at the end. It kind of brought me back to that feeling of why I fell in love with playing the guitar in the first place. When I can get to that mental place with my instrument, I feel at home.”

With Up Close, Johnson has returned home in another way by signing once again with EMI after issuing a handful of releases on Steve Vai’s Favored Nations label. Although the guitarist admits that Capitol/EMI dropped him when 1996’s Venus Isle failed to match the sales of Ah Via Musicom, he’s happy to have the backing once again of the global powerhouse for Up Close, which is labeled an EMI/Vortexan release. “Vortexan is the part of the label I set up so that I can retain control over my music,” he explains. “I tried doing things a different way, the more indie route, and that was fine. But I think it’s important to have as much machinery behind you as you can, distribution-wise and promotion-wise—especially these days, when you’re up against so much in trying to get your music out there.”

And Johnson isn’t averse to reaching fans via unconventional routes, such as video games. Since its inclusion in Guitar Hero III in 2007, “Cliffs of Dover” has been one of the most popular tracks of the game franchise. “I don’t have a problem with the whole video game thing,” he says. “Whether or not people pick up real guitars after playing the games, I can’t say. But it’s interesting to me how the guitar has become this iconic image in pop culture. The instrument and its application in music are constantly evolving. I’m just trying to find my own way.”

With the release of Up Close, Johnson’s fans are simply hoping that the guitarist finds his way to the stage. Not that he’s been a total recluse. Since 2008, he’s taken part in three Experience Hendrix tours, and come January he’s set to embark on the second leg of the all-acoustic Guitar Masters tour (which also features Peppino D’Agostino and YouTube phenom Andy McKee). But hearing their hero perform a full set of his own galvanizing electric music is what the guitarist’s admirers are clamoring for. Johnson says an Up Close tour is in the works but not imminent. “I do plan on hitting the road for the new record, probably in the spring,” he says. “I’ve got to put a new band together and get out there. The guys I was playing with have sort’ve moved on, so I’ve got to find some people and see if I can get some chemistry going. And I think it might be fun to find somebody else to sing and play some guitar and keyboards —you know, shake things up a bit. Right now, I don’t want to repeat what I’ve done before. I’ve gotta go somewhere new.”

GUITAR WORLD Before we talk about Up Close, I want to ask you about Jimi Hendrix, who has been such an influence on your playing style. Do you think it’s possible, in this day and age, that somebody can come along and have the same impact that he did on guitarists in 1967?

ERIC JOHNSON I do think somebody can still have that kind of impact on musicians. I’d hate to think that it’s all been done. Will that person be playing the guitar? I don’t know. Possibly. But to do that, that person is going to have to throw out a large portion of the rulebook. There’s so much that’s been established on the guitar—accepted patterns and norms—and it’s all one big comfort zone. Face it: the foundations of rock guitar are based so much on the pentatonic scale. We all use it. We come out and play patterns and licks and solos that mix up that same set of notes. So whoever changes things around is going to have to do something radically different.

GW But Hendrix adhered to certain established “rules” as well. He was schooled in the blues, and a lot of his playing had its foundation in the very thing you’re talking about, the pentatonic scale.

JOHNSON Yeah, but he amped things up to such a degree. He made it seem so different. And it wasn’t so much that he made it seem different; he was different. He was one of the first generation of guys who cranked up the fuzz and the feedback and turned things inside out. B.B. King was experimenting with that, and so were guys like Link Wray and Jeff Beck. But to blow it all to pieces in such a psychedelic way, with rock and blues and some jazz coming together as one—it was extraordinary.

Plus there was his tone: I remember when I first heard the album Are You Experienced, I wasn’t even sure I was hearing a guy play the guitar. [laughs] I was just getting past surf music and the early British rock, and here came this guy who just blew everyone away. Can somebody do that again? I hope so. It’d be cool to have that happen again. Will it happen during my lifetime? Time will tell.

GW The title Up Close is sort of generic, but in fact the title has a very specific and important meaning to you.

JOHNSON Yeah, it does. It’s basically me saying, Okay, I’m going to expose more of myself than I have before. It’s time that I let the gates down and show myself, you know? Even with the lyrics to the vocal tunes, they’re probably some of the most personal and intimate things I’ve ever written. This record is the beginning in many ways. It’s me trying to play more, show more, just be in the moment more than I ever have been.

GW Five years have passed between Bloom and Up Close. Were there any changes to how you approached recording?

JOHNSON Yeah, there were. Even though I did spend a bunch of time on the new record, I know I spent much less time than on other records, which is a step in the right direction. I just tried to let go, to be more open to spontaneity and intimacy.

GW Is that hard for you, though? I get the feeling that letting go doesn’t come easily to you. You like to hold on to your recordings and labor over them, almost to the point of what some have called “obsessiveness.”

JOHNSON [laughs] That could be true. With me, I have to satisfy the intellect. Without a doubt, though, I have to realize that certain applications just won’t pay off the dividends that I thought they would. With this record, I had to understand that the most important thing I had to do was make better music and play the guitar to the best of my ability, but not at the expense of the songs themselves. The more I crystallized that priority in my life, the more it became comfortable for me to be open and let things happen naturally.

It’s weird: I got to a place mentally where I said, I don’t always want to react to life. You know what I mean? I don’t always want to be acting or reacting; I want to be breathing life. We create our own reality by what we think and project. It sounds trite, but the truth is, if you can change your own life then you can change the world. I guess that’s a funny way of saying that I know I have to be free with what I’m doing and not beat stuff to death.

GW It sounds like you had quite an epiphany. Was there a specific occurrence that brought this about?

JOHNSON Yeah, I just started to accept that whenever people had certain criticisms about the way I was making music, what they were giving me was a gift—they weren’t just getting on my case. If they didn’t think that I had talent or what I was doing wasn’t any good, they wouldn’t say anything at all. So a doorway started opening, and I stopped looking at what people were saying as, you know, just one giant bummer.

Trying to make better music and improve as a player and make something artistic…there’s no one recipe. I used to think there was. I thought, Well, this is how I’m supposed to do this, and this is how that’s gotta be done, and so on. Throwing out those notions has been very liberating. Of course, it’s taken me years to get to this place, but better late than never.

Something I want to add to that, and this might help illustrate my whole philosophy: I’m starting to think that people don’t really go out to listen to music. They might think they are, but what they’re really looking for is the spirit behind the music. They’re looking for something that moves them and touches them. But you can’t move people unless you’re inspired yourself. That’s something I’ve had to grapple with—inspiration versus craft. You can work on your craft and polish something and hone it, but if you’re just beating your head against the wall, what are you really doing? I used to think that I was making things better, but I’ve started to come around to the way of thinking that maybe things were coming out a little sterile.

GW So everything that you’re saying comes down to one thing: you had to stop fussing around so much. [laughs]

JOHNSON Well, sure. It’s like, a painter might make 100 paintings in his lifetime, but the world might only praise 10 of them. Does that mean that the other 90 are worthless? Of course not. So I had to… [pauses] I had to realize that myopically holding on to one song for so long wasn’t going to matter in the long run—because I’ve got 80 or 90 more songs to do! It’s like, if Jonny Lang can sing “Austin” better than me, then so be it. That means there’s another 40 I can try to sing myself. It’s all about trying to make better music, making that connection.

GW Did you have any kind of set schedule for recording Up Close? Because you have your own studio, are you always working in fits and starts, or did you have an actual date when you got the other musicians in and formally began sessions?

JOHNSON It kind of happened over time. Like you said, I’m pretty much always writing songs and getting ideas, so it wasn’t like I decided one day, All right, today’s the day when I start to make my new record. Being that I’m my own producer and work with Richard Mullen, who co-produces with me, I have the luxury to work when I want. But the writing process and the gathering of information never ends. I’m always writing things down on paper and making tapes and filing them away. I might call the guys up and say, “Hey, let’s try to do some recording today.” And if the song works out, great; if not, then I’ve got a good demo that I can resort to at some future date.

I do work on my own a lot, though. If I get an idea at home, I’ll go work on it and try to get it as definitive as possible. I’m proficient enough on most of the instruments I need to work with, although I’ll use a drum machine or a metronome for the rhythms. There were some times on this record where the band got together and we went for it.

GW In terms of subject matter, the state of Texas looms large on the album. You cover the Electric Flag song “Texas,” and of course you have “Austin” and the song “Vortexan”… Coincidence or intentional?

JOHNSON It just kind of happened, really. I was always going to put “Austin” on the record. As far as “Texas” goes, I had cut a blues track, and then Steve Miller came in and was going to sing, and he heard what we did and said, “Man, I’d love to sing ‘Texas’ over that.” It wasn’t necessarily supposed to be the Electric Flag song. Roscoe and Tommy and I had cut a first-take blues track, and it pretty much lent itself to what Steve wanted to do. It’s amazing, really, because I love that Electric Flag record [1968’s A Long Time Comin’]—I pretty much wore it out as a kid—but I didn’t think of covering anything from it. Yeah, that was a nice bit of spontaneity.

GW And it doesn’t hurt the Texas vibe that you have Jimmie Vaughan guesting on the track as well.

JOHNSON That’s pretty cool, huh? Jimmie’s amazing. He came in and overdubbed his parts. I didn’t have to give him any kind of direction or anything; he knew what to do. Man, I’m such a fan of his playing. I could listen to him all day and all night.

GW By the way, just what in the world is a “Vortexan”?

JOHNSON [laughs] Oh, that’s a funny name somebody called me. I was in Sedona, Arizona, and a friend of mine was talking about how spacey the place is and how there’s all these vortexes and stuff, and he looked at me and said, “And you’re the Vortexan!” I thought that was a great title. The song is a pretty cool blues, kind of like Robert Johnson’s “Cat’s Squirrel” and a little bit like my song “Righteous.” I like it a lot.

GW This is an Eric Johnson record, yet it’s loaded with guest stars. Did it ever concern you that your fans might think they weren’t getting enough Eric Johnson?

JOHNSON Listening to the finished record, my only concern was that I wished I could have played guitar with more reckless abandon. It’s like, I should have more fun and let go. The record’s a little tame and in its place.

GW But I thought the whole idea was to let go more!

JOHNSON It was, but I don’t know if I got there all the way. I think this record is a step in the right direction. Put it this way: it’s much better than Bloom. With Bloom, I wish I could call it all back and redo the whole album. Give me that record for three days, man, and let me go nuts. That record’s sedate. I just… I want to figure out how to get more. More and more and more. I want to get less conservative in the studio and have fun and get crazy. There’s got to be a way to be more intense without stepping all over the songs.

GW Well, I would say you’ve done a pretty good job on the new album.

JOHNSON Yeah, thanks. I just know I can get closer. I have no problem with the amount of guest stars on the record. People are getting enough of me. They’re my songs. I’m playing on them. If somebody sings a song better than me, that’s fine. It all contributes to the whole.

GW The three interludes—“Awaken,” “Traverse” and “The Sea and the Mountain”—started out as one whole song. How and why did they become separate pieces?

JOHNSON I originally recorded the whole piece, and I tried all kinds of versions of it and placing it everywhere on the record, and I could never be happy with it. The flow of the record wouldn’t work with it, but I didn’t want to lose it, either. So somebody suggested to me the idea of cutting it up into three different parts, and it worked out really well. Suddenly, I had my opening for the album, “Awaken,” and then I had my middle, “Traverse,” and with “The Sea and the Mountain,” I kind of had almost the closing chapter. It’s weird how it all came about, but I’m so glad I chopped it up. Each piece feels more dramatic now. But I will say, with “Awaken” I had to fight myself wanting to hard edit that into “Fatdaddy” [the following track], because that would be exactly what I did with “Cliffs of Dover.” So now it kinds of fades out and goes into “Fatdaddy.” It’s cool. I can live with it.

GW The song “Soul Surprise” is a great instrumental, but it didn’t start out that way. Originally, you wanted Paul Rodgers to sing on the track.

JOHNSON That’s right. I’m such a fan of Paul Rodgers. He’s one of my favorite, all-time singers. But I could never come up with a compelling vocal melody for the song, and I wasn’t going to have him come in and sing on something I wasn’t totally thrilled with. If I’m going to do work with Paul Rodgers, I want it to be worth his while; it’s gotta be worth his talent. So yeah, “Soul Surprise” just seemed to want to be an instrumental. I struggled with it a bit. I liked the track, I liked the way the guys played on it, but whenever I tried putting guide vocals down on it, it sounded very normal and rehashed to me. It’s good now. I really enjoy the groove on it and how it sounds like a Free-inspired tune, which it is, of course. [sighs] It just didn’t want to be a vocal song.

GW Your soloing on “Gem” is gorgeous. You wrote that song for a friend of yours, right?

JOHNSON Yeah, it’s kind of a tribute to a good friend of mine. There’s a few songs that I directed toward certain people.

GW I would think “Your Book,” on which you play piano, is one you aimed at specific people in your life.

JOHNSON Oh yeah. I wrote that about my father, who died a few years ago. With that one, I started thinking about how everybody has a story, and that story is their book. Think about it: how many times have you gone to see a movie and you said, “Well, that was good, but the book was so much better”? That’s what I was trying to get at with “Your Book.” I was trying to put into words my father’s story, or at least what I thought his story should be.

GW Is it hard for you to write about something so personal, or is it a catharsis? Is it liberating to be able to get such emotional baggage out in your work?

JOHNSON It’s both. It’s hard, but…more and more, it’s liberating, yeah. I have a whole different side to me, which is me playing the piano. I get to explore a lot of personal stuff on the piano. You know, when I started playing the guitar, it was cool and people seemed to really like it, so I rolled with it, you know? But doing acoustic shows and playing the piano, I started getting feedback that people really enjoyed it. So to answer your question, whether it’s a catharsis or not, I think that’s always been there, but I’ve edited it; I’ve always removed myself from the experience. Lately, I’m not.

GW As you get older, does it become easier to trust your emotional instincts?

JOHNSON Absolutely. As you go through life, you get to a place where you can trust your feelings and not be afraid to share them. It might have taken me a while longer than a lot of artists, but I feel as though I’m finding that place, for sure. You know, when you’re young, you can’t show all your cards to people; you gotta be cool and stuff. But now, I’m at a place where if I see a flower and it turns me on, I’m going to say, “Hey, isn’t that a beautiful flower?” And I know it’s all right to say that. I’m having an experience, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

GW Let’s talk gear. As far as guitars and amps go, what combination of instruments and gear works best for you?

JOHNSON My amps are really well put together by Bill Webb [of Fullton-Webb], [high-end audio products designer] George Alessandro or [Austin Tone Lab founder] Bill Ussery. Those three guys are amazing when it comes to tuning stuff and making everything just right. But the amps are pretty much stock. I use Blackface Twin Reverbs. For dirty rhythm, I’ll use either a Fulton-Webb dirty rhythm amp or a Dumble amp. For leads, I’ll use either a 50- or a 100-watt Marshall head.

These days I rely pretty exclusively on my signature Fender Strats. I worked with Michael Braun [principal engineer, guitar design] at Fender to design my own pickups. I wanted to get them balanced, and I wanted the bridge pickup to be hot but not at the sake of losing the clean tone. That’s really the key—having just enough clean and dirty going at the same time.

GW Besides your signature Strats, you do have some vintage models, though, right?

JOHNSON Right now, I only have a ’57. [He leans right into the recorder, cups his hand at the mic] But I am looking for a ’54! [laughs] I had a real nice ’54, but I sold it. Oh, but I do have a fantastic Gibson ES-335 from 1964. That’s a really beautiful instrument. I don’t need a lot of guitars, though. I used to have a bunch, but I found that I wasn’t using them.

GW How did you record the solos on the new record? Did you do multiple takes and comp them?

JOHNSON Actually, on this record, I trusted my first instincts more than I ever had before. The three sound pieces, that whole thing was one giant take—just me going for it. “Texas” was a first-take solo. The ending solo on “Arithmetic,” I did that probably 10 times and I was never happy with it. So one day, I just said, “Hey, it’s just a bunch of notes. Let’s roll tape.” And whatever came out was what I stuck with. I had to beat myself up a bit to reach that point of spontaneity. It’s a process I’m exploring. [pauses, smiles] But you know, there’s still one little note that bugs me in that solo…

GW You’ll never be satisfied.

JOHNSON [laughs] No, I’m cool with it. I’m learning. I’m trusting that what comes out is what’s meant to come out. I’m believing that what’s going on is bigger than me. I’m seeing the value in that. This record, like I said, is a starting point for so much of what’s to come. And I know my best work is ahead of me because of where I am mentally.

GW Do you practice the guitar much, or are you at the point where you don’t really need to?

JOHNSON Oh, no. I definitely need to play and practice. I practice every day, in fact. If I don’t, I get rusty. [laughs]

GW Are there specific areas of your playing you want to try to improve?

JOHNSON Yeah, I’d like to learn more chords. I feel pretty good about my soloing and all that, but chords… There’s so many I still don’t know. I think if I was more versed in that aspect of the guitar, my music would grow exponentially.

GW Going back to your sound, let me ask you something: Do you ever feel pressure to reproduce that famous tone? Does the weight of people’s expectations ever get to you?

JOHNSON It’s funny: I was talking to my girlfriend, Erin, about that very thing last night. I think it all comes down to ego. I know when I go onstage I sometimes have that feeling: I gotta blow these people away tonight. But it’s a two-way street. It’s based on your own perception of yourself, and then it comes down to what you think people expect of you. So what you have to do is remove yourself and just be. Be in the moment. I’ve had a couple of nights on the Hendrix tour where I really enjoyed every second of it, but I think what made that possible is that I didn’t think of anything—I just played.

I know what you’re talking about, though. It’s hard to get out of the way of your ego, particularly once you start becoming known for whatever. I think the important thing is not to think of people’s expectations as a burden, and not to think of your own expectations as a burden, either. You just have to try to enjoy the experience of playing music. More and more, that’s where I want to be.

"The BTO sound is BACK!!" Bachman-Turner Overdrive release first new material in over 25 years – and it features a Neil Young guitar solo

“He would beat the crap out of the guitar. The result can best be described as Jackson Pollock trying to play like John Lee Hooker”: Aggressively bizarre, Captain Beefheart's Trout Mask Replica remains one of the craziest guitar-driven albums ever made