“Musically, Eric was a very generous guy. I loved working with him because he encouraged me to play”: How Eric Clapton used Roger Waters, George Harrison, and Stevie Ray Vaughan as foils to survive the ‘80s – the decade he was not prepared for

This was the decade that saw Slowhand board a train with Another Ticket and disembark as a fully-fledged Journeyman. Here, Albert Lee, Phil Palmer, and more recall a turbulent time in Clapton's career

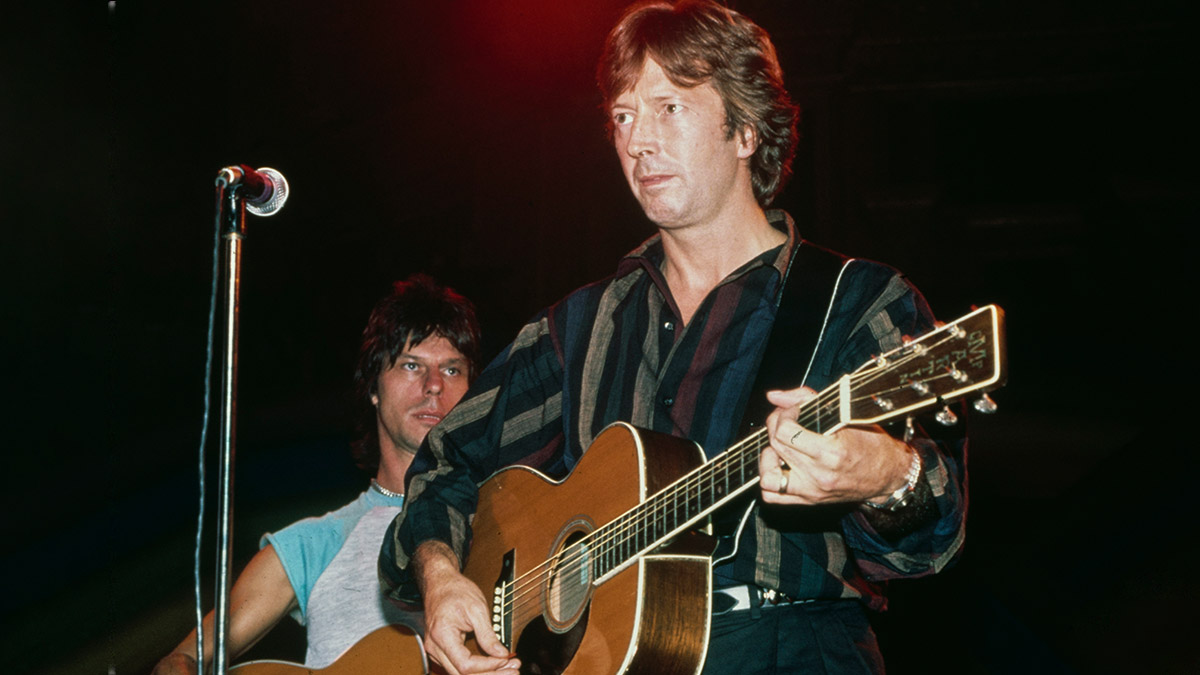

Despite kicking things off with a bang alongside Jeff Beck for 1981’s Amnesty International benefit in London, which many signaled as “a return to form,” Eric Clapton wasn’t ready for the Eighties.

It seems obvious now, but looking back, even Clapton would probably agree. To that end, the downfall, if you could call it that, wasn’t so much steep as it was somber, with Clapton progressively moving away from his patented “woman tone,” which had come by way of blending various humbucker-equipped guitars with cranked Marshall amps.

Going into the Seventies, Clapton was still considered “God” by some. But by 1980, at 35, he was perhaps one of your lesser gods, shelling out soft rock accented by even softer – but still kinda bluesy – licks.

But it wasn’t all bad, as by the early Eighties, Clapton had assembled a rocking, all-British band featuring Gary Brooker on keys, Dave Markee on bass, Henry Spinetti (younger brother of actor Victor Spinetti, who starred in three Beatles movies) on drums, and most importantly, the ever-capable and entirely essential Albert Lee on guitar.

When Lee wandered into Clapton’s camp in 1978, the idea was to spice up Clapton’s backing band.

“We’d known each other for a long time, and we ended up doing a session together in London in 1978 for Marc Benno,” Lee says. “We played together for a week on that. At the end of the session, Eric’s manager [Roger Forrester] came up to me and said, ‘How would you feel about coming out on the road with Eric to play second guitar?’ I thought, ‘That sounds like fun’ – and off we went.”

Considering that Clapton was grappling with self-inflicted issues including (but not limited to) drug and alcohol addiction, Lee coming along wasn’t just about providing a capable live partner; with his fingerstyle approach and hybrid-picking technique that was entirely different from Clapton’s, Lee brought new flavors and positive energy to the party. Moreover, he inserted some sorely needed blues edginess – or call it country sharpness – into a mix that had become increasingly soft-rock.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Despite the softness seeping its way into his studio recordings, once on the road with Lee, Clapton seemed invigorated, leading to the recording of two December 1979 performances at Budokan Theater in Tokyo that became the beloved 1980 double live album, Just One Night.

Unlike what was to come, Just One Night found Clapton and friends brimming with passion and raw energy (case in point: the band’s dramatic, eight-minute-long take on Otis Rush’s Double Trouble). More memorable still is the fact that the record showcases the interplay between Clapton and Lee – especially when it came to their respective solos on the extended version of J.J. Cale’s Cocaine.

I never really felt it was a guitar battle. I felt it was a conversation, really

Albert Lee

It’s important to know that Lee – despite the pride associated with the performance (he played the country-tinged second solo while Clapton played the bluesy first solo) – doesn’t quite look at it that way.

“I never really felt it was a guitar battle,” Lee says. “I felt it was a conversation, really. Also, I sang two or three songs [including Setting Me Up and Rick Danko’s vocal parts on All Our Past Times]. Throughout the whole time I was with Eric, really, I was the harmony singer. There were no girl singers in those years. It was mainly down to me.”

One would’ve assumed that Clapton would take the energy he found on the road into the studio for his next record, and its title, Another Ticket, seemed to foreshadow as much. Instead, when Clapton and his band hit Compass Point Studios in Nassau, Bahamas, in 1980, the edge that once defined him was still missing in action.

Retrospect says that 1981’s Another Ticket was a modest success, as evidenced by its position at Number 18 on the U.K. charts (and the Top 10 status of its Clapton-penned single, I Can’t Stand It).

But Clapton’s music was never meant to be modest – especially with such a rocking yet blues-leaning band. That’s not to say Another Ticket is poor; it’s more to say that at 35, it seemed Clapton was more interested in blues complacency than juicing up the genre as he had a decade prior.

Still, Floating Bridge features some interesting tones, and the overall tragic nature of the album, which centers around death – and in the case of Rita Mae, murder – could be seen as an example of Clapton leaning into his blues heritage, albeit in a highly mellowed-out fashion. Indeed, it seems Slowhand was wallowing in misery by this time, which is precisely why Another Ticket is a bit low on gusto.

It was bad enough that Clapton had gone from innovative dragon slayer to a yacht rock-leaning softy nearly overnight, leading to cookie-cutter album after cookie-cutter album.

But making matters worse – and this was nothing new by the early Eighties – was his worsening alcoholism, which by 1982 had reached code red status. Somewhere in between fits of complacency and a sudden ‘come to Jesus’ moment that saw him “deepen his commitment to Christianity,” Clapton checked himself into rehab to sort himself out.

In the lowest moments of my life, the only reason I didn’t commit suicide was that I knew I wouldn’t be able to drink anymore if I were dead

Eric Clapton

Specifically, he checked himself in during January 1982 – but not before hopping on a plane and drinking himself into oblivion one last time out of fear that he’d never drink again.That sounds pretty damn awful, and according to Clapton, it was.

“In the lowest moments of my life, the only reason I didn’t commit suicide was that I knew I wouldn’t be able to drink anymore if I were dead,” Clapton said in his autobiography. “It was the only thing I thought was worth living for, and the idea that people were about to try and remove me from alcohol was so terrible that I drank and drank and drank, and they had to practically carry me to the clinic.”

Despite doctors’ orders not to engage in activities that would trigger alcohol consumption or stress, Clapton, seemingly brimming with energy, hit the studio to record what would be his next album, 1983’s Money and Cigarettes, a name chosen because Clapton is said to have felt that those two things were all he had left.

Sadly, Clapton’s new and more clear-headed lease on life did not result in a change of musical course, with Money and Cigarettes providing more of the same low-energy content he’d been perpetrating since the mid-to-late Seventies. The only difference is that now Clapton couldn’t lean on addiction as an excuse for his amour-propre.

And to be sure, it wasn’t his band’s fault, either – especially given that slide ace Ry Cooder and master bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn were added to the mix, moves that should have been inspiring. But this was Clapton, after all, and while Money and Cigarettes might have been past its sell-by date out of the gate, it does have its moments, such as Man in Love, the All Along the Watchtower-esque Ain’t Going Down and – best of all – the blazing six-string interplay between Clapton and Lee on The Shape You’re In, which Lee remembers well.

“We had such different approaches to the music,” he says. “I was always very conscious about trying to accompany and supplement what he was doing. That’s what people pay to hear, and he was happy to let me step out and play.”

Money and Cigarettes dropped in February of 1983 and was touted as a comeback album, which was to feature a sober and supposedly more creative Clapton. But success was again measured in modesty, with the album topping out at Number 20 in several countries. In short, this was not a level of success for someone who had achieved “God” status.

Another wrinkle showed up when a younger, hipper, far more aggressive-sounding (and also Strat-wielding) gunslinger from Texas – Stevie Ray Vaughan – inserted himself into the conversation via his debut record, Texas Flood, which was released in June 1983.

For too long, Clapton had been asleep at the wheel, mainly providing records to use as white noise for lazy drives through the countryside or the desert. It had been years since he unleashed himself and made his Strat squeal, but now SRV was here with a record stacked with tracks to bump, grind, and sweat to – including Love Struck Baby, Pride and Joy, and his version of Buddy Guy’s Mary Had a Little Lamb – quite possibly leaving Clapton a smidge envious.

For the first time since the aforementioned “Clapton is God” graffiti, Clapton’s status as a premier bluesbreaker had been challenged. And while you might think his ego and track record kept him from caring, if Albert Lee is to be believed, Clapton was, at the very least, listening to what SRV was doing.

“[Eric] got a great joy out of listening to other guitarists,” Lee says. “He especially loved Stevie Ray.” Literally within months of Texas Flood's release, Clapton changed his style, guitar tone, and overall vibe to something – well, with a bit more heft to it. More on that later.

Looking back on his time with Clapton, Lee says, “I think I did a pretty good job, but I never really looked at the whole deal as me competing with him. We were all there to make music, and my style worked alongside him. It was complementary rather than competitive.”

Meanwhile, SRV released another barnburner of a record in 1984’s Couldn’t Stand the Weather, further loosening Clapton’s once ironclad grip on blues-rock guitar. Vaughan also was being compared (in these very pages) to Jimi Hendrix; after all, he was serving up blistering covers of Voodoo Child (Slight Return), Little Wing, and Third Stone from the Sun night after night.

But Clapton had a retort of sorts – 1984’s masterful The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking – which saw him partnering up with Roger Waters for the latter’s first post-Pink Floyd foray. Once he was perched beside Waters, Clapton was a man on fire, dishing out solos that still read back as some of the best of his career.

To this point, Clapton had made a tactical error by meandering around and releasing blues-like but mostly blues-adjacent pop filler, forsaking the “song within the song” approach that many of his Cream, Blind Faith, and Derek and the Dominos solos had shown. But with Waters – as evidenced by songs like 5:01 AM (The Pros and Cons of Hitchhiking) and 4:41 AM (Sexual Revolution) – Clapton threw everything he had at the wall, and nearly all of it stuck.

In short, the album and its subsequent tour showcased the array of E minor, heavily compressed, tone-perfect solos and riffs that proved Clapton could still be “God” – even if SRV were here to stay; and SRV wasn’t going anywhere. But that shouldn’t have been an issue, as Clapton was back amid the conversation and primed and ready to take on the remainder of the Eighties, right?

You would have thought that, and in some ways, it was true. Yes, Clapton did revamp his look, tone, and approach. And yes, he was prepared to back up the success alongside Waters with his own success. But the thing is, Clapton wasn’t ready for the Eighties, and by late 1984, he had become painfully aware of that. And so, while on a split from his wife, Pattie Boyd, Clapton teamed up with – and this still seems odd – Phil Collins to help right the ship, along with legendary producer Ted Templeman, resulting in 1985’s Behind the Sun.

One of the most significant issues with Clapton's work, dating back to the mid-Seventies, was that his guitar playing had taken a backseat to whatever sounds he felt would grant him chart success, stripping him of what made him great in the first place.

Surely, Clapton was aware of this – especially with the guitar-forward SRV gobbling up headlines and air time – and Behind the Sun certainly has its share of memorable solos and riffs.

So that was one problem sorted; but now, another presented itself, which admittedly is subjective: an over-reliance – probably at the behest of Collins – on drum machines and synthesizers.

Case in point, here’s how Guitar World put it back in 2015: “The last minute and a half of Just Like a Prisoner might represent Clapton’s mid-Eighties high-water mark, at least from a shred perspective. The song features what could easily be considered one of his ‘angriest’ solos.

“He even keeps playing long after the intended fade-out point, until the band stops abruptly. Maybe he was upset about the overpowering Eighties production, ridiculous synthesizers and obtrusive, way-too-loud drums that threaten to hijack the song at any moment.”

But on the bright side, while Clapton’s old band was gone, Behind the Sun does feature a ton of quality players, such as Fleetwood Mac’s Lindsey Buckingham, who played rhythm guitar on Something’s Happening, and Toto’s Steve Lukather on See What Love Can Do and the album’s most memorable track, the polarizing yet beloved Forever Man.

Looking back on how he ended up at the Behind the Sun sessions, Lukather almost seems embarrassed, saying, “I wasn’t very important to the album at all. Honestly, I feel like I did very little in those sessions. I remember being very nervous and thinking I should play really simple so that people wouldn’t even know I was there.”

As for Clapton’s state of mind at a time when the urgency to deliver a competitive record must have been at the forefront, Lukather says, “Eric was really nice to me, but we weren’t close. I added very little to his stuff, I think. I remember walking in, and Eric examined my fingers and said, ‘You don’t have any calluses.’ He seemed disappointed, but I had just gotten out of the shower, so my hands were soft!”

Indeed, Clapton now seemed ready for the Eighties… or he was at least prepared to try and sound like something out of the Eighties.

On the strength, if you could call it that, of Templeman and Collins’ techy production, Clapton had a hit on his hands. Forever Man was very well received, even if it, along with the rest of the album, sounded more akin to Steve Winwood a la High Life than anything he’d done back when he was universally considered the greatest guitarist on the planet.

The reinvigorated Clapton wasn’t letting any time go to waste, either. Only a year after Behind the Sun (not to mention the Edge of Darkness soundtrack, which he recorded with Michael Kamen), he delivered the super-slick August, which was successful courtesy of tracks It’s in the Way That You Use It and Tearing Us Apart, which featured Tina Turner.

But retrospect tells a different story, and it’s hard to deny that August is probably Clapton’s worst record – especially as far as the Eighties are concerned. Not even a track like Miss You, which features some of Clapton’s most inspired playing of the decade, could save an album entirely bogged down by synths, gated reverb, and guitars that are often buried in the mix.

In his search for success, Clapton not only fell off the wagon of sobriety but also saw his marriage to Boyd come to an end. The latter was a bit of karma, seeing as he’d stolen her from his best friend, George Harrison, in the Seventies, but the former was especially unfortunate, as it came at a time when Clapton was seen as regaining his footing.

In the wake of a second and still successful trip to rehab, Clapton emerged prepared to reclaim the throne again. And much like he had with Waters in ’84, he set his own music aside and played session man, this time for Harrison, who was due for a renaissance of his own – and got one via 1987’s Cloud Nine.

It was a serendipitous meeting of musical minds – with Clapton seemingly unencumbered by the pressures of measuring up to his past, he laid down some of his best Eighties work on tracks like Cloud 9, That’s What It Takes, Devil’s Radio, and Wreck of the Hesperus.

On the backside of those tracks, among other hits, Cloud Nine was a success, and a now sober and soon-to-be-single Clapton began ruminating on his next move, seeing him begin to write many of the songs that would appear on his final – and best – album of the Eighties, Journeyman.

Everything about Journeyman was different. For starters, it came on the heels of the successful (and truly awesome) 1988 box set, Crossroads, which showcased many of Clapton’s older and sometimes out-of-print-on-vinyl hits to a new and now CD-consuming generation.

The positive reception for Crossroads, coupled with the fact that SRV had been slightly down for the count while battling his own addiction demons, allowed Clapton the space to reorient himself.

Moreover, Clapton had found himself, meaning he rediscovered that long-lost “woman tone” he’d been missing, much of which can be attributed to his new signature Fender Stratocaster. Yes, Journeyman has its share of Eighties production – no one can deny that. But it’s also loaded with blues numbers, including Before You Accuse Me, Running on Faith, and Hard Times.

A critical addition to the sessions was Robert Cray, who lent his licks to six of the album’s 12 tracks and even co-wrote Old Love with Clapton. Sadly, Cray declined to be interviewed for this story; however, another venerable six-string veteran – Phil Palmer – also played a role on Journeyman, especially the album’s signature track, Bad Love.

“I had run into Eric in a little club in London called the Mean Fiddler,” Palmer says. “I looked up while playing and was shocked to see Eric standing there. Long story short, we got to talking, and Eric said to me, ‘Phil, it’s nice to see you. I’m making a record, and I’d like you to drop by and play on a few tracks.’ I did so, and the first track we did was Bad Love.”

Looking back on how he approached the track, given that his fingerstyle approach was in stark contrast to Clapton’s, Palmer says, “Musically, Eric was a very generous guy. I loved working with him because he encouraged me to play. Of course, you have to learn not to step on what Eric’s doing, but through my session work, I’d learned how to adapt, and Eric had a good way of letting me know in an unspoken way when I should jump in. He’d give a nod, and off I’d go.”

Of note, Palmer is only credited with lending a hand to Bad Love, but he recalls being heavily involved with two additional tracks, Old Love and Running on Faith, saying, “Eric encouraged me to play loud, which was like a dream come true. I wasn’t always encouraged to do that in other sessions, but Eric did.

“And I remember that by that point, I’d gotten the idea that my long-used [Fender] Nocaster was pretty valuable, so I didn’t use that with Eric. Eric supplied me with one of his signature Strats, which were great guitars put together in the Fender Custom Shop. I still use them.”

Looking back, it’s easy to see why Journeyman is considered Clapton’s best album of the Eighties, even if some reviewers, such as Robert Christgau, likened it to a “fluke,” saying, “[Clapton] has no record-making knack. He farms out the songs, sings them competently enough and marks them with his guitar, which sounds kind of like Mark Knopfler’s.”

That’s harsh criticism, and perhaps there’s some truth to it, but regardless, Journeyman gave Clapton the success and singularity he needed. Moreover, it finally gave him something to compete against SRV, who released his own comeback album (of sorts) in 1989, In Step. But this time, Clapton bettered SRV, as Journeyman reached Number 1 on the Album Rock Chart and landed him a Grammy for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance in 1990. Not too shabby.

As for Palmer, he stayed on with Clapton, hitting the road in support of Journeyman and proving his most capable sideman since Lee left him half a decade prior. Looking back, Palmer says, “That album was just great… but it’s hard to quantify. The band was magnificent, and spontaneous things would happen daily.”

As for what he learned from Clapton, Palmer says, “The biggest lesson I got from Eric was to relax. I played with him hundreds of times, and when I stood behind him on stage, I saw that he was most at home. Maybe not in the studio, but live, Eric was free. He wasn’t nervous on stage, so that was the biggest lesson – to enjoy the moment.”

Palmer makes a good point: Clapton was always freer on stage than in the studio. It’s probably why he kicked off the decade so successfully with Just One Night, and it’s perhaps why many felt his appearance alongside Jeff Beck at the Amnesty International benefit would signal a return to form. And if he’d carried that same vigor into the studio, we’d look back on Clapton’s decade in the doldrums a bit differently.

But then again, it wasn’t all bad, and some of us, even though albums like Behind the Sun and August play back more like dollar bin and thrift store fodder than albums to remember, have a ton of personal memories tied to the likes of Forever Man, It’s in the Way That You Use It, and She’s Waiting. And to be sure, no one can take away the God-like strokes of genius heard on Clapton’s collaborations with Roger Waters, and to a lesser extent, George Harrison.

And so, the Eighties did little to encourage the idea that Clapton was “God,” but in the end, it didn’t entirely dispel the notion, either. As for Lee, when he looks back, he admits, “I haven’t listened back [to Clapton’s Eighties music] in a long time, so I can’t name a specific track. But I like the later stuff; the solos are really melodic, even though I’m not really into Eric for the guitar solos. I think he’s a great writer and a really good singer. The whole package works for me as a listener.”

As for Lukather, who sheepishly lent a hand to one of Clapton’s most polarizing Eighties moments in Forever Man, he seems to echo Lee’s sentiment, saying, “I am embarrassed even to be a part of the whole thing, but Eric is great. He was a huge influence on me, and I wore his stuff out. What can I say that hasn’t already been said?”

While the Eighties may have been choppy for Clapton, if anything, what he’ll most be remembered for is the redemptive way he rounded the decade out. In truth, not many artists could survive such critical onslaught, the unintentional creation of eventual thrift store fodder and those perpetual assertions of “God” status being revoked, but Clapton did.

And so, for Eric Clapton, the Eighties wasn’t only about music or even about guitar; it was about across-the-board survival and living to fight another day. Clapton might not have been ready for the Eighties, but he sure as hell did his damnedest to survive them – and to eventually come out on top.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

“I suppose I felt that I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I’d put into it. My head was huge!” “Clapton is God” graffiti made him a guitar legend when he was barely 20 – he says he was far from uncomfortable with the adulation at the time

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul