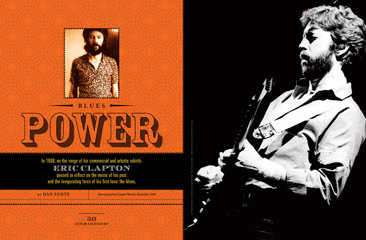

Eric Clapton: Blues Power

In 1988, on the verge of his commercial and artistic rebirth, Eric Clapton paused to reflect on the music of his past and the invigorating force of his first love: the blues.

By the time Eric Clapton encountered the MTV generation in the mid Eighties, his short but profound stints with the Yardbirds, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Cream, Blind Faith and Derek and the Dominos seemed a lifetime past. He had become a performer of hits like “Forever Man” and “It’s in the Way That You Use It,” a composer of soundtracks for The Color of Money and Lethal Weapon and the man who stole the show at the 1985 Live Aid concert.

The success of 1988’s Crossroads retrospective box set put his history back into proper perspective. At the time of this interview in late 1989, he had just released Journeyman, an album that marked the beginning of his commercial and artistic resurgence. For the album, Clapton was joined by longtime friend George Harrison, but it his work on it with blues guitarist Robert Cray that stood out. Trading solos with Cray on Bo Diddley’s “Before You Accuse Me” and playing funky slide licks on Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog,” Clapton sounded like both student and master, retaining the raw enthusiasm for the blues that he had in his youth while displaying the maturity of a bluesman with more than 25 years under his belt.

GUITAR WORLD Nearly all of the material on Journeyman came from outside sources.

ERIC CLAPTON I was really having a difficult time writing, this last year or two. Nothing came until halfway through the sessions. I had a week’s rest in England and going back to New York I caught the flu. I knew Robert Cray was going to be in, and suddenly I was faced with the fact that we didn’t have anything to do—which is how “Before You Accuse Me” came about. “Let’s do that. It’s simple and we both know it.” That’s Crazy [Cray] and me intertwining all through the song. He plays the second solo. Then I was in my hotel room just playing around with a riff, and it ended up being “Old Love.” Robert wrote the turnaround and the bridge. He takes the first solo and the ride at the end, and I kind of chip in here and there. I wrote “Bad Love” right at the very end, because Warner Bros., as is their wont, came in and said, “Well, where’s ‘Layla’?” [laughs] I methodically thought about it and said, “Well, I’ll get a riff, I’ll modulate into the verse, and there’ll be a chorus where we go into a minor key with a little guitar line. Then there’ll be a breakdown and I’ll put ‘Badge’ in for good measure.”

GW There are some nice, extremely long bends in the solo.

CLAPTON My fingers suddenly seem stronger than they’ve ever been. I find that I’m now bending, like, five frets—which is more than I normally do—and holding it. Bending up there and then getting vibrato, which is something I’ve never been able to do before.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

GW There’s a lot of wah-wah on this record.

CLAPTON Yeah, I’ve always liked wah-wah, but I was scared of it for a while, because it became very fashionable in the Philadelphia sound and then sort of burned out. So I thought, Stay clear of this for a bit. I’ve always liked the Hendrix wah-wah stuff, and I was in the avant-garde of that, too, with “Tales of Brave Ulysses.” I bought my wah-wah in Manny’s in 1967, and I did “Tales of Brave Ulysses” in New York, I think, the same day—just experimenting with it.

GW What was it like, recording and living in New York while you were working on Journeyman?

CLAPTON I was there for three months, and I loved it. I like working in L.A., too, but you seem to get more done a lot quicker in New York, and the musicians you use there—like Richard Tee and Eddie Martinez—are so quick. Their attitude is so good, and there’s not a lot of bullshit. It’s just work, work, work. I was generally working till 11 at night and going to bed.

GW Were there other guitarists, besides those already mentioned?

CLAPTON Just George [Harrison]. He came in for a week, and we did five of his songs—some of his spare songs and some he’d written especially for the album—and ended up using just one ballad, “Run So Far.” It’s a [Traveling] Wilburys-type thing, because he’s very much a Wilbury at the moment. That was the only one of all of his songs that didn’t have his augmented chord in it, which drives me crazy. It’s lovely when it’s with him—you know the one I’m talking about—but when I do it, it’s a little bit wrong for me.

GW When we spoke last year, you said that the next album—your first new album since August— would probably be more of a straight-ahead rocker. Do you view this album that way, or did you change your mind along the way?

CLAPTON I think it changed a little bit in the making. Pretty early into the sessions we found that the material we were looking for would end up being like rock and roll material. When we did “Hard Times” I said, “This is the kind of album I want to make,” and Russ [Titleman, the album’s producer] said, “Well, let’s do that next. Definitely.” And I figured, to be fair to Russ, I had to go along with that, because to get him as my producer the first time out and limit him to something is not necessarily very fulfilling for him as a producer. Given the fact that he made that smash hit album for Steve Winwood, I wanted to give him his head, too. As part of our relationship, we kind of agreed that we would postpone a blues album until our next project. So that is concrete.

GW That’s been the rumor on the street, but along with it was a rumor that this was going to be your last Warner Bros. album and that you’d get out of that contract in order to do a blues album next time.

CLAPTON The thing was, while we were doing this album and talking about the blues album, I was saying to Russ that I didn’t think Warners would validate such a kind of limited-interest thing. He approached [Warner Bros. president] Lenny Waronker and told him that that’s what we planned to do, and that even if Russ didn’t do it for Warners, we’d do it for another label. And, I suppose because he sensed that I would leave the label, Lenny said, “Great idea. I’m all for it.” So I stay with Warners and do what I want to do in the meantime. But I think having left a partnership with Phil Collins, it was crucial that they got another fairly commercial album from me first.

GW It’s surprising, though, how much control Warner Bros. wields. In 1985 you explained that “Forever Man” and a few others were made—at their behest—after you’d delivered them your original version of Behind The Sun [Clapton’s 1985 album]. In the process they rejected “Heaven Is One Step Away,” which is one of the best recent songs in the Crossroads box.

CLAPTON Well, in hindsight, it’s worked out to everyone’s satisfaction. I had a lot of resentment at the time, and I still harbor a little bit, but to be fair I think they’re the record company with the greatest access to the people. They have the best distribution and best promotion in the world, so if I want to get my music out, and it’s not too much of a hardship to play ball with them, I’m quite happy to do it. And I do like Lenny and Mo [Ostin] a lot, because they are producers of music and they know what it’s about. And the fact that they did give me a go-ahead for the blues album kind of gave me faith in the relationship again.

GW But if Eric Clapton can’t go in and give them the album he wants to do without compromises, how would a less proven act fare?

CLAPTON But it was very character building for me to have to face that, and I am grateful for that situation. It lopped a lot off my ego and gave me a little taste of humility, which I may have been in great need of.

GW With this record and August [Clapton’s 1986 album], it sounds as if you’ve been listening to a lot of soul in the past few years.

CLAPTON I’ve been listening to a lot of Aretha [Franklin]’s early stuff—not out of a plan; just because it happened to be convenient and close at hand. I’ve actually got in my car that album that I played one track on, Lady Soul [featuring “Good to Me As I Am to You”], and I listen to that a lot. The way the band is arranged and everything is a great inspiration. There’s a great deal of simplicity there, and at the same time it’s really very well organized.

GW Even though Journeyman has a lot of different feels, including the old-time rock things, “Hound Dog” and “Before You Accuse Me,” it doesn’t really have a “Rita Mae” or “Ain’t Goin’ Down”– a full-tilt fast rocker. Was that a conscious decision, or were you not able to come up with one?

CLAPTON It wasn’t that we couldn’t come up with one; I just wasn’t writing that way. Yeah, it would have been nice. The closest you get to that is “Bad Love,” and I’m not even sure if that isn’t too fast. I was kind of staying away from belters, though I don’t know why. Until we added a couple of songs, it was very much a midrange- tempo album—a lot of slow tunes. Maybe I’m mellowing out a bit too much… I don’t know.

GW That is an “accusation” that the press has leveled at you as well as Winwood and Phil Collins.

CLAPTON I don’t see it, really, because the intensity is there at the same time.

GW Do you think it would be justified if guys who’ve been around as long as you three choose to just make some nice, catchy tunes?

CLAPTON Yeah, I think that’s perfectly justified, but I don’t think you could sum up this album like that. When we were cutting tracks and when I sang on them, I was doing it to the utmost of my intensity. If that is mellow, then that’s what’s happening, you know. That’s a natural progression. But it doesn’t feel like that to me.

GW The magnitude of Crossroads reinforces something you, in certain respects, have tried to downplay: the Clapton-as-biggerthan- life-guitar-hero. Not only in terms of yourself, but in general, how do you view the so-called “guitar hero”? Do you think it’s a valid thing, a tasteless exercise…

CLAPTON No, I think it’s very admirable, and I think it strengthens a belief that kept me going for years—that you have to have an ideal. And if I have to be a hero, even to myself, it’s worth it, because it’s something to strive for. I quite like having my mettle tested in that way. I didn’t like it not so long ago; I tried to avoid it, to play it down, and tried to destroy it. And that process nearly destroyed me, too, as a human being. I found that one went with the other: in order to be a growing human being, you have to keep pushing yourself to the limit. To try to go inward or backward is actually very, very destructive. I find now that I’m actually quite happy to try and perpetuate this myth, even to myself. I mean, I was in Africa this last tour, where I had to fill out all these forms each time we changed countries. And where it said “Occupation,” I put “Legend.” [laughs] I couldn’t have done that 10 years ago; I took it all far too seriously.

GW You must be aware that certain critics will inevitably slag you because “this has all been done” and “the days of guitar heroes are over.” Does that ever inspire you to go out and say, “I’ll show them who’s washed up!”

CLAPTON Oh, it does even now. On this record I was determined to make each solo as outside my capabilities as possible, to push myself as far as I could—even if it was just in terms of how many frets you can bend. “Anything for Your Love” has got Robert playing on it, and when I did the solo on that, I looked at him, and he was amazed that I had this one note—I just push it—at the end of a phrase. He was just blown away. So if I can do that to him…

And that really reflects on what I think about critics. I don’t think they have much experience to talk from, except for listening. It’s my peers that count, and if I get criticism from them, if they think I’m going in the wrong direction or not living up to my capability, then I’ll take it onboard. The last time that something hurt me involved Elvis Costello. I mean, I consider him a peer because we’re in the same business. I’m not that well acquainted with this music or anything, but I consider him to be very serious. And he wrote me off. It had to do with the beer-commercial syndrome and all that. [In the mid Eighties, Clapton recorded the J.J. Cale song “After Midnight” for a Michelob beer commercial. Clapton had previously recorded the track for his self-titled 1970 solo debut.] He’s got a bit of a soapbox about that, you know. He said that he could understand certain people who’ve got something to say doing it, but as far as he was concerned, I’d said it all and had nothing left to offer. So that, coming from a peer, is hurtful. But that will make me strive more than anything a critic will say. When a musician runs me down, then I want to prove something to him.

GW Between the period with Tim Renwick and when you teamed up with Mark Knopfler, you were the only guitarist in your band. Was that rough?

CLAPTON No, I love it. In many ways, you sacrifice a lot when you bring another great guitar player in. It’s kind of a novelty at first; it’s something you have to get over. With Mark I went through a great deal of being in awe, and again with Phil [Palmer]. The first week or two of playing together, I was listening to him too much, being too self-conscious about the situation. But when you get over that, you get used to him being there. I don’t ignore him, but I just go ahead as if there was no other guitar player. And I’m quite narrow and selfish, both about my boundaries and where my limits are. I don’t let anyone try and knock me off.

GW With someone as unique as Knopfler, do you ever find yourself being influenced by them?

CLAPTON Not at all, no. They have their thing, I have mine. I’m actually still more influenced by records than by other players. I still try to steer myself towards my early heroes. The only person that I would be severely influenced by is Robert Cray. I mean, during that whole week when we did these things together for the album, I found I was playing far above my normal standard. I had to, because he’s such a consummate and total musician that you have to be ready day and night. He’s like a ninja. [laughs]

Normally, put into that situation, most guitar players are hit and miss; they might take two or three passes at something. Robert doesn’t—it’s first time, every time. That’s very rare, and when you’re around it, it keeps you on your toes. I would love to be in that situation all the time, but at the same time I’m a man of leisure these days. I don’t wish to be on the road 360 days a year, which is what Robert does. He doesn’t have anywhere to live. [laughs] It’s a steady joke. I ask him, “Have you got anywhere to live yet?” “No.” He doesn’t have a house. So I don’t really want to be in that place. I’ve been there, and I don’t want to play every day anymore. And that’s what it takes.

GW In two instances I can think of—the Freddie King (1934–1976) album and the [1986 ITV1] South Bank TV special with Buddy Guy— you sounded almost exactly like the hero you were jamming with. Was that intentional?

CLAPTON Sure. I mean, you’re paying respect to the form. It would be completely fruitless for me to be playing onstage with Buddy and come out with some kind of Zeppelin-style guitar solo. I have to respect not just him but the form of the music. And what I loved first and foremost about the blues was that it had a very severe, strict form—one which you pay a great deal of attention to. There are certain notes you play for a turnaround, at the beginning of a solo, for the entry into passages. It’s just as rigorous as classical music, in a sense. You have to pay respect to it. So when I’m around those guys, and when we’re seriously trying to do something special, then that’s the way I’ll play. And I thank God I have enough experience and I studied it enough in my youth to know what not to do—which is more the case that what to do.

GW These days, the name that does seem to come up a lot, in terms of influences, is Buddy Guy’s. But at the time of, say, the Blues Breakers album, there was more of a Freddie King or Otis Rush element. Who were your influences prior to that?

CLAPTON Well, in the Yardbirds we were trying to stay away from the classical stuff, the betterknown stuff, as we knew it. So we were doing songs by Snooky Pryor or Eddie Taylor, who were more the Chicago kind of sidemen who were making records of their own but weren’t necessarily as well known, because we were trying to make them sound like our original material. If we did a classic Freddie King, B.B. King or Buddy Guy song, we would seem to be paying homage; when we did a Snooky Pryor song or one by the guy who did “Wish You Would”—Billy Boy Arnold—it sounded like the Yardbirds, because nobody knew who those guys were.

In fact, all of these songs came off one album that we ripped off. It was a compilation album called “Chicago Blues” or something [Bluesville Chicago, Vol. I, Top Rank (France)], and it had all those songs—“I Wish You Would,” “Judgment Day,” “Bad Boy.” That was our set—we just did that album. Even though I was aware of, and was learning to play from, Freddie’s records and Buddy’s records and Otis’s, we avoided that as material.

And not to put these other guys down, but they were easier to cover. The great songs like [Otis Rush’s] “Groaning the Blues” or “Double Trouble” would be so hard for, first off, a vocalist to cover. Not so bad for the band or a guitar player—they can somehow get by—but a vocalist is the man in the pole position, and he’s got to be able to do as well, if not better [than the original]. And not too many people in this country ever made it that far.

GW As you said, growing up in England, you were dependent on whatever blues records filtered over and whichever touring artists appeared. As a result, do you think your image of blues was more romantic?

CLAPTON Yes, absolutely. And the love affair, the obsession with the blues, was reinforced by the fact that it was so inaccessible. And having made a little inroad into it, I was one of the few who had not only the taste for it but the gift for it, too, and I belonged to this incredibly exclusive club whose members included Keith Richards and Mick [Green of Johnny Kidd and the Pirates] and [Fleetwood Mac founder] Peter Green and people like that, who had, like, a mission. We were crusaders in a way, and that was a great, secure feeling for a person of my type, who came from a very sort of nowhere place, to have somewhere really worthwhile to go.

GW Were you happy when someone finally unearthed photos of Robert Johnson?

CLAPTON Yeah. As much as they can find is not enough. I mean, the music still transcends it all, but it’s nice to have artifacts, too.

GW But as long as no one knew what he looked like, he was part man, part myth.

CLAPTON But you can preserve that. I think it’s possible to leave your fantasies there. My fantasy of Robert Johnson exists in my head no matter what the reality of what his picture looks like. I still see another person. But it’s close—that’s the great thing. It’s still a story that has to be properly told.

GW Not that it was a strict bio of Robert Johnson, but you must have been disappointed in the film Crossroads, for the trite way that it portrayed blues.

CLAPTON Yeah, and the concept of the guitar duel at the end was just appalling—so disappointing. I mean, the way the kid won was to revert to some kind of classical piece. What did that have to do with fucking anything?

GW One of the charms of the early British blues is that the bands were obviously so enthusiastic about the music that they went into it headlong; and that while some of the lesser bands were probably a bit too reverent, the really special ones used the records as launching pads rather than textbooks. Your version of “Hideaway” on the Blues Breakers album is a perfect example. Was it hard to find other players who had the facility to go beyond the originals?

CLAPTON I wasn’t looking for other players to play with. I had a very competitive mind. I didn’t want there to be any other players that had that facility. So it was enough for me to be in a band that could go with me in that direction. Pete Green and Jeff Beck were the only other players who could touch on material and then go way from it. Jeff particularly.

For instance, there’s a standing joke with him and me about this song “Wee Wee Baby,” off the Folk Festival of the Blues album. Buddy Guy kicks it off, and it’s such a random start, no one seems to know how it’s going to go. And Jeff’s got that down so that it sounds positive and rambling at the same time. But then he’d go off, you know? It’s funny, but musicians of that ilk often tend to stay away from one another—they keep their distance because they want to stay in that space where they’re untouchable.

GW Prior to joining the Yardbirds, what band did you sing in, and what was your material?

CLAPTON I had been singing with the Stones, and on one occasion I’d put together a band consisting of me and a drummer to play a local dance. I sang everything— Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley— just R&B mainly. In the Yardbirds, it was assumed that Keith [Relf] was the singer. It wasn’t up to me to actually decide anything at all. I had a very small voice in the band. It wasn’t until later, when I started getting a following of my own, that the rest of the band considered me to have any input at all. And then I would say, “Let’s do ‘Good Morning, Little Schoolgirl,’ ” and I would get a chance to sing. I didn’t push myself, because I was still more interested in being the guitar player.

GW These days a lot of people seem to dump on the Yardbirds because…

CLAPTON Is that so?

GW Well, in the South Bank special about you, for instance, Pete Townshend said that, apart from you, “they really were a shambles.”

CLAPTON Well, you know, Pete, for instance, had a different perspective on the whole thing. He was into Martha & the Vandellas and Tamla/Motown, and what we were doing didn’t really register. He only became aware of the great blues musicians much later in his career. He was a pop musician from the word “go,” and that’s not a slam on his character or way of thinking—he just came in from a different place.

And the Yardbirds liked to listen to “Five Long Years” by Eddie Boyd. That’s what we listened to, and in what we played even then there was a great chasm of difference. We thought something like “I’m a Man” was pretty commercial compared to what we were listening to, because we were all into Jesse Fuller or Furry Lewis. Those records were gold dust to us. We were country blues fanatics, but to play we had to have records to emulate that had drums and bass and guitars. So they had to be R&B records.

GW As for the blues records that managed to filter over to England, you managed to luck out a lot, in terms of getting really good stuff.

CLAPTON Well, that’s not true. No, there was a great deal of discrimination involved, too. There were a lot of other things. We had Josh White, who came to England almost once a year, and for most people, he was the blues. But I saw through that. I don’t know what gave me the insight, but to me Jesse Fuller on that one album [Jazz, Folk Songs, Spiritual & Blues (Good Time Jazz)] had far more real feeling than Josh White ever did. But that was what was available, and there was lot of that stuff being dished over here. So, yeah, there was a lot of discrimination involved, too. Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee came here too, and they were great, but I remember thinking, There has to be something more. When they came to these shores, they were far heavier than anything we’d experienced before, but still I had an inkling that there was something more intense. I don’t know what gave me that insight—I thank God for it, to this day—but I just knew.

GW What was the first thing you uncovered that sort of struck that chord?

CLAPTON Without a doubt, it was Freddie King: “I Love the Woman,” on the B-side of “Hide Away.” That just sent me into a complete kind of ecstasy, and it scared the shit out of me. I’d never heard anything like it, and I thought I’d never ever get anywhere near it. And I know now that I never will, but it was what immediately made me want to carry on.

GW Freddie King’s solos and choruses on his instrumentals are about as perfect as anyone could ask for—like compositions unto themselves.

CLAPTON They are. His taste was like that. He never played anything that you could imagine him regretting.

GW In addition to the usual Cream reunion rumor, there’s a new one going around—that the Bluesbreakers will have a reunion.

CLAPTON That’s definite. The rumor about Cream was invented from the outside. It never occurred to me, and I’m actually not that keen to ever try it, to be honest, because there was such a great gulf of difference between me and Jack [Bruce] and Ginger [Baker], even when we were together. But there is a definite plan to do a tribute to John in November. I don’t know if we’re going to do an album, a show, a concert or what. [Fleetwood Mac’s] John McVie and Mick Fleetwood are doing it, and it would be great if Pete Green could come out of retirement, but I don’t know if that’s possible. I met him on the street not more than a year ago, and to me he’s a great guy, and he was just the same. He didn’t look particularly healthy, and he seemed like he was kind of pissed off in general, but that’s quite a healthy attitude to have, in some respects. It’s not as if he was indifferent. So I would never completely give up on the guy.

GW Didn’t he visit you at home a few years back?

CLAPTON Yeah, I took him in for about three weeks and listened to him whine and moan about the business and life in general, and I would kind of absorb it all, and I’d just keep playing music—which in the summertime I do anyway. In the morning I get up and I put music on—opera, classical music, guitar music, blues, jazz, all kinds—all day. After he was there about a week, I noticed him dancing in the garden one day—so he was changing. And he actually left with a very different, positive outlook. It just seemed to be a healing experience for him, because to have music played to you by someone else takes away your responsibility. You can just enjoy without having to choose or contribute anything. It was good for him. And I’d happily do it again; I love the guy very much.

GW Did he pick up a guitar while he was there?

CLAPTON No, we didn’t play, and I didn’t want to put him in that position. He may have played while I wasn’t looking or wasn’t around—that’s extremely likely. But the last time I saw him, he’d deliberately grown his fingernails so long that he couldn’t play. When you get that angry, it’s healthy, and I think he’ll probably come out sooner or later.

GW He sure was great.

CLAPTON One of the best—he really is. And I’m not gonna say, “was,” either. He is one of the best. It’s all there.

GW What’s your view of reunions, in general—like the Who or the Stones?

CLAPTON I think they’re great—if there’s something there that they all want to go through again. I don’t particularly know how Pete [Townshend] feels about it; I know from what I heard that in the last days of the Who when they were working a lot, it was a painful experience for him, and having lost Keith they just felt that they were going through the motions. And if you go through that for a long time, there must be a lot to get over when you do reunite. The Stones, too. Knowing the enmity that’s existed between Keith and Mick for so long, it must be tough—a lot to get over. But that, in a sense, is a great character- building process, too. I’ve been around those guys—most recently when Bill [Wyman, former Stones bassist] got married, I saw them all back together again—and when they’re together, even though they may have their differences, they are such a powerful gang of people. They rise above all kinds of hierarchies when they’re together. They’re strong, strong, strong, and it makes you feel really good to be anywhere near it. So I’d like to see them on tour again, but it doesn’t always work. I think in the case of the Stones, it will work. But with Cream, I don’t think it would.

GW Why not?

CLAPTON Because I don’t think the desire is there. If Ginger’s got a strong desire to get it back again, I think it’s nostalgia more than anything else. I don’t think there’s a desire to create anything new. For me, it would be very difficult to conceive of creating anything new with those guys.

GW When they reunited you and Jack Bruce on the South Bank special, what was great was that, even though it was a special about you, he was playing on your turf—literally on your back porch. He wasn’t going to be denied. His ego was as strong as ever.

CLAPTON To be honest, that’s one thing that prevents me from going back: my ego would have to just disappear altogether. Though I’m sure they would respect my ideas, because those guys are very aggressive and forceful, I know that when it came down to the first day on the floor, they would just be scraggling for the front.

GW Probably more so than before.

CLAPTON Yeah, even more so than they were then. I can’t work with that anymore; I don’t want to work in that anymore. I like a laidback, easy attitude, and that’s what I get when I’m the boss. People that work with me will tell you it’s a very easy situation; I don’t come down hard on anyone, and I don’t give them too many hard things to do. So it’s fun, and I like to keep it that way. It wouldn’t be fun with Cream; it would be fuckin’ hard work. Although it may produce great results, it would just be a very arduous process—something I’m not that keen on.

GW As the one guy who calls the shots, being able to have things your way, do you think there’s an element that’s missing in, say, not having a bass player that challenges you the way Jack did?

CLAPTON I’m sure. But, no, Nathan [East] does that as much as I need him to, and more. You see, as much as I love Jack’s playing, Nathan is more of a blues player than Jack is, you know—and more of a rock and roll player, too. Jack has a much more jazz-oriented slant on the whole thing. So I prefer to play with Nathan.

GW But aside from playing—the personality…

CLAPTON Well, I’m in a position now to choose, man. I mean, if I had to work with Cream because I had no other work, I would do it. But if I’ve got the choice, I’ll play with the band that I select. And I wouldn’t select those guys to be in my band because they are lead musicians. I’d have to get out of the way. And I don’t want to get out of the fuckin’ way; I want to be in the front now. Maybe I didn’t then, but I do now.

GW Could we chronologically run down the various guitars you’ve used in your career? After the hollowbody Kay Jazz II you played in the Roosters, with the Yardbirds you used a Tele, an ES- 335 and a Jazzmaster.

CLAPTON The Kay was the guitar that my grandmother bought me on the “high-purchase” scheme. That got me into the band, and then we started making money, I found I had nothing else to spend it on but guitars, so maybe once a month I bought a guitar. The unfortunate thing was I didn’t keep them. The only one I’ve still got is the 335; it’s the oldest guitar in my collection. Well, not the oldest, but the one I’ve had the longest. It’s beautiful. But I had the Jazzmaster, the Tele, and also at one time I think a Silvertone that looked just like Jimmy Reed’s.

GW Do you remember which of those guitars you used for the Yardbirds’ recordings?

CLAPTON I think the Tele. Or the Gibson, but more likely the Tele, because I remember breaking strings a lot, and that’s why I moved to the Tele.

GW Is the Bluesbreakers-period Les Paul the one that was stolen?

CLAPTON Yes, that one was stolen during rehearsals for Cream.

GW So you didn’t use it on Fresh Cream?

CLAPTON No, I borrowed a guitar for that; it was a borrowed Les Paul. I went through quite a few and until about five years ago never got one that was anywhere near the original one in terms of the neck shape and fingerboard.

GW Both Blues Breakers and Fresh Cream have such classic Les Paul tones. They were both played through Marshall amps. Were they different types of Marshalls?

CLAPTON Yeah, I think on Fresh Cream we had a bigger, 100-watt [a JTM45 rather than the 50-watt 1962 combo].

GW Did you know that Marshall has reissued the 1962 combo as “The Bluesbreaker”?

CLAPTON Did they really? How sweet. I didn’t even know that. How does it sound? You know, that’s be good, because I’m always looking for something to replace this Fender tweed [Twin]. You can’t take it on the road; it’s pretty unreliable. So to have something of that strength that would be reliable would be worth looking into.

GW When you switched to the psychedelic-painted ’61 SG/Les Paul onstage with Cream, did you also use it in the studio?

CLAPTON Yeah, Disraeli Gears, I think, and from then on, really, a lot of the time. That became my mainstay until I bought a Gibson Firebird with one pickup, and that for a time became my most favorite guitar. All during Cream I didn’t really have a favorite guitar because I never really replaced the Les Paul, and I was constantly searching for something to come up to scratch. I’d play the ES-335, or the SG or this Firebird. I don’t think I had a Fender—I think it was only Gibsons—but I may have toyed with it.

GW The ’61 SG/Les Paul must have come with the big sideways vibrato tailpiece.

CLAPTON It came with the sideways tremolo on it, which I took apart, but I kept the bridge and the tailpiece. I never liked tremolos; I’ve never been able to stand the bloody things. Eventually I put a stop tailpiece on it.

GW At the debut performance of Blind Faith, you played a bound Telecaster with a Strat neck. Was that an idea you had?

CLAPTON Yeah, I had probably two or three Strats, and I never liked the Tele neck. And I thought it would be unusual and might have people guessing what kind of guitar it was because of the head.

GW The Strat first became your trademark on the Eric Clapton solo album. Is that the same Strat that was used on Layla?

CLAPTON Yeah, the brown [sunburst] one [a.k.a. “Blackie”].

GW A lot of Strat players, like Jimmie Vaughan and early Buddy Guy, get a twangy sound without a lot of sustain, but you get a lot of sustain with a Strat. Is that a product of your vibrato?

CLAPTON It’s that and a combination of the new active system in my particular guitar. If you jack that up a bit, it doesn’t give you more sustain than when it’s flat. And the old tweed Fender Twin, which is my number-one amp in the studio: I found it at Pete’s Guitars in Minneapolis–St. Paul years ago. It’s been rewired several times, because it heats up. Cesar Diaz came in and insulated everything with this extra-strong cable, because it would melt after you played it for a while.

GW Did you use the Eric Clapton Signature model on Journeyman?

CLAPTON Exclusively, yeah. The only song I don’t use it on is “Hard Times,” where I used the ES-335 to get a kind of an old studio sound, a more acoustic blues guitar tone.

GW Do you currently own a Les Paul?

CLAPTON Yes, a very, very good one that’s almost identical to the one that was stolen.

GW Do you ever feel like breaking it out for that Bluesbreakers type of sound?

CLAPTON I don’t really get into that, because it’s too reminiscent of Cream, I think. I don’t think about the Bluesbreakers as much as I do about Cream and that thick, solid, Gibson sound. I like to approach that, which I can do with a Fender, but I don’t like to be limited to it, which is what you have with a Les Paul—you’re stuck with that, really. But you can get close to that, and have it, in fact, with a Strat—or you can back off on it, too.

GW Let’s talk some more about amps. What did you play through in the Yardbirds?

CLAPTON Umm, I think they were Vox. An AC30.

GW With Cream you used a 100- watt JTM45 stack?

CLAPTON Two of them.

GW To get the so-called “woman tone” on Disraeli Gears were you still playing through the same setup—the SG/Les Paul and Marshall stack—with the guitar’s tone backed off?

CLAPTON With the tone backed off on the neck pickup.

GW Backed off how much?

CLAPTON All the way, and full volume.

GW What amps did you use during the Layla sessions?

CLAPTON During the album? [Fender] Champs. Onstage, I’m not so sure: Marshalls or maybe a Fender Showman, because I would want to keep the Champ sound, but just have it bigger. Which isn’t what happened, but that’s what you think the idea would be.

GW At some point in the Seventies, you switched to Music Man amps. Were those the first mastervolume amps you used?

CLAPTON That was the first time I ran into that concept, and to this day I still find it very hard to get along with. I don’t like too many options in an amplifier. The simplicity of an early Fender is what I want. If I want it to distort, I’ll just turn it up full volume, and it will do that. But when you’ve got all these permutations, you just spend too long fiddling around on the knobs.

GW In your soundtrack work, do you feel as though you’re coming up with a certain approach, or is it strictly a product of the story and characters in each case?

CLAPTON It depends on the project. On [the 1988 film] Homeboy, I got a lot of feedback from the director and the producers. They wanted a specific thing to echo the character played by Mickey Rourke; they wanted to have an element of country, an element of blues; they wanted it to be wistful and slightly melancholic. So they were with me while I wrote the melodies and recorded them, and they had a lot to say about it. That’s how that one came about, but internally I’m always pretty sure of what I want to do, and if they don’t agree I’ll generally override them— unless they’re really definite about something.

But that film was a bit of a disaster because we finished it, and then sent it off to Mickey, and he didn’t like it. He said the music didn’t echo his character strongly enough. So then the director walked off, and Mickey came and started recutting the film to make this character stronger. And I had to recut some of the music with Mickey directing me. I have yet to see the finished project, but it felt better with him involved.

The other one, Lethal Weapon 2, I did while I was doing Journeyman. It was a joy to do because I was involved with Michael Kamen and David Sanborn again—this time live with David. For the original Lethal Weapon, we recorded with him in the States and me in England, but this time we actually had a chance to play off one another. We took each main theme and extended it to make a record, so it’s going to be a killer album, one of the strongest things I’ve done.

GW When you record your blues album, will you work with your own band or will you seek out musicians who play blues exclusively for a living?

CLAPTON The plan as it stands is to recreate the kind of Texas blues band that Bobby Blue Bland had. If I can, I’ll get [saxophonists] Fathead Newman and Hank Crawford again and supplement them with other horns, and also Johnny Johnson, from Chuck Berry’s band, on piano, and try to make a hybrid that isn’t particularly Texas or Chicago but has the elements of each—and then just superimpose myself on top.

We’ll do material which has already been done—“Five Long Years” maybe, or “She Moves Me” and some Muddy songs and early Bobby Bland things—but mix it all up. The reason I’ve gone on this, and I think it could be a success, is that one track I did for The Color of Money, which never made it to the album—you can only hear it in the film way in the background— was a version of “It’s My Life” by Bobby Blues Bland, backed by a little English blues band called the Bigtown Playboys. Have you seen them? They’re great. The keyboard player [Mike Sanchez] is unbelievable. He has it down. We did the session in a day, and that’s what’s inspired me to go ahead on this. I want to do it with a fairly big band; I don’t want to do a country blues album. Sophisticated arrangements and modern. I’m not looking for authenticity, just feeling.