Eric Clapton: The Artist Formerly Known as God

Originally printed in Guitar World, May 1998

On Pilgrim, Eric Clapton demon- strated that there’s more to salvation than a heavenly guitar solo.

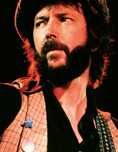

It was in the early Sixties that Eric Clapton first grabbed people with the scream in his sound. People called it the “woman tone,” but that was no woman—that was his life. On songs like “Born Under a Bad Sign” and “Crossroads,” he used his guitar to give voice to the emotions he couldn’t, or wouldn’t, vent as a singer or songwriter.

That changed with Pilgrim. Released in 1998, it was Clapton’s first full album of new material in more than eight years. Compared to much of Clapton’s past work, Pilgrim found him standing up to some powerful ghosts: Stevie Ray Vaughan, with whom he was touring at the time of the guitarist’s death, in 1989; Clapton’s four-year-old son Conor, who died in 1991 and was the inspiration for Clapton’s 1992 hit “Tears in Heaven”; and his own father, whom Clapton had never known and whose absence informs the Pilgrim track “My Father’s Eyes.” “‘My Father’s Eyes’ is very personal,” said Clapton. “I realized that the closest I ever came to looking in my father’s eyes was when I looked into my son’s eyes.”

And, unlike in the past, he did not rely on his guitar playing alone to do the dirty work. On Pilgrim, Clapton rose to the challenge posed by his uncommonly revealing lyrics by taking some uncommon risks vocally. From the raucous bluesy shouting of “Sick and Tired” to the technically demanding ornamentation of “Broken Hearted,” he sang the album’s tracks with the same controlled abandon once associated only with his guitar playing.

GUITAR WORLD What significance does your album’s title, Pilgrim, hold for you?

ERIC CLAPTON I think everybody has their own way of looking at their lives as some kind of pilgrimage. Some people will see their role as a pilgrim in terms of setting up a fine family, or establishing a business inheritance. Everyone’s got their own definition. Mine, I suppose, is to know myself. That’s probably as close as I can get to it. My goal is to really come to identify who I am to myself.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

GW The album represents a breakthrough for you in terms of songwriting: you wrote 12 of its 14 songs. It’s been almost a decade since you’ve even come close to being this prolific. Was composing the songs on this album important to your process of self-discovery?

CLAPTON Absolutely. As you’ve observed, my normal output is usually much less than this. Actually, that used to be the way I wanted it. I would always want no more than two or three of my songs on an album because I just didn’t want to reveal myself.

It wasn’t cowardice. Or maybe it was. Maybe it was a mixture of cowardice and insecurity, or just low self-esteem. In the past I would think, What have I got to say that’s any better than, say, [songwriter] Jerry Williams? or whoever else was contributing songs to my albums. But on Pilgrim, I started developing a really healthy respect for my own talent.

GW Who or what was responsible for this dramatic change?

CLAPTON It was primarily due to working with [keyboardist and Pilgrim co-producer] Simon Climie, who was very encouraging and very supportive. I could always rely on him to be an objective sounding board. He gave me confidence, and then once he brought it out there was no stopping me. I could’ve carried on writing, but we’d actually ended up with more than we needed. We went in with virtually nothing, so the great thing was that it evolved and got written as we went along.

GW In the past, you’ve been content to let your guitar do the talking. I get the feeling that, these days, that just isn’t enough for you, that you want to take the same kinds of chances with your songwriting and singing that are usually associated with your playing.

CLAPTON You’re right. I originally set a wide-open boundary on this record, and once I knew that I’d stepped over the time limit, I thought, Now that we’ve taken this chance, we might as well go for broke and just get everything as far out as possible.

I just feel like I’ve become a little more whole in terms of how I see myself as a singer-songwriter- musician. There is a better balance now among the components than there was before. I remember when I thought of singing as the bit that went between the guitar playing—something I couldn’t wait to get out of the way. Singing was originally like a chore that I didn’t really enjoy. Now all of the components are completely integrated, equally important and really dependent on one another. I now enjoy singing as much as the guitar playing, if not more sometimes.

GW And the lyrics, too, I imagine.

CLAPTON Absolutely. The writing, too.

GW This is going to sound a tad pretentious, but would you say that the artist has an obligation to reveal himself—to bare his soul?

CLAPTON I can only speak for myself, but I believe it is my responsibility to do so. But to do so with care, as well.

GW Responsibility to whom? To yourself or to your audience?

CLAPTON To myself, and to the nature of the human race, really. I feel a real need to observe a level of propriety in what I’m handing out. Instead of me just venting or spilling my guts, I’ve got to consider how it’s going to affect people. How it’s going to affect me, as well, because it’s like a cycle.

I’ve kind of learned to embrace that responsibility, and it makes me work harder. Instead of just chucking out the first thing that comes to mind or the first thing I feel, I really examine it much more now and go over it and think about cause and effect.

GW Is the process joyful or painful?

CLAPTON Joyful, but in an odd way. When I first conceived this album, I told anybody who was going to get involved that my goal was to make the saddest record that’s ever been made. It was like, “Are you with me, man and boy?” A couple of people responded by looking at me like I was insane, that this was not a good ambition. [laughs]

The first person who totally understood where I was coming from was [noted session drummer] Steve Gadd, who said, “Yes! I get the point!” He understood that what I was trying to do was set something up that I could enjoy, because my enlightenment has come from true sadness. When I hear very sad records, I don’t get depressed. I feel an affinity and I feel relief. The first thing I get is a sense of, I am not alone. Thank God! I’m not alone.

GW How difficult was it to take previously private feelings about specific tragedies in your life and express them artistically?

CLAPTON It was difficult. For instance, the first draft of “My Father’s Eyes” came out sounding pretty petulant. The lyrics were too angry and childish. Where the art and craft came in was in being able to shape the anger into something people could empathize with. It wouldn’t work for me to just kind of sulk in the song, because it wouldn’t have communicated. Instead of feeling an affinity, people would’ve been repelled.

So I felt the way to make “My Father’s Eyes” into a sharing experience was to give it dignity, so that it would make it easy for someone else to identify with. That’s where the craft comes in. It’s learning how to use the power of your emotions, but figuring out how to present it in a way that makes it okay for someone else to take that onboard as being their message.

“My Father’s Eyes” was the hardest song to record on the album. It was one of the first songs, along with “Circus,” that I wrote after my son died. And it was the last one that I could let go of. In fact, I found “Circus” a lot easier to let go of. “My Father’s Eyes” went through five incarnations in the making of this record, and I would veto it each time and say each wasn’t good enough.

In retrospect, I question what I was up to, because at the time it was purely from an artistic point of view that I said, “it’s too fast,” or “it’s too jolly,” or “it’s too sad.” Now, I actually think subconsciously I just wasn’t ready to let it go, because it meant, on some level, letting go of my son.

GW Did writing and recording “My Father’s Eyes” and “Circus” help you cope with the loss of your child?

CLAPTON Music was very important. Talking about it with friends and seeking professional help were also crucial. Confronting it head-on was the best thing for me. It was very important that I be responsible, because there were others besides myself who needed comfort.

GW “River of Tears” is perhaps one of the most passionate vocal performances of your career. Given the personal nature of this album, can we assume that it, too, is autobiographical?

CLAPTON “River of Tears” was recorded very early in the Pilgrim sessions, and I can remember thinking, This is as good as anything I’ve ever heard myself do. In fact, it became the standard for the rest of the album. I didn’t want anything else to fall below that.

Lyrically, it is about a specific person. My impulse for writing the song was initially very manipulative. I was always toying with the idea that when she’d hear this song there would be a reconciliation or something. It had a purpose.

And then it started getting vindictive. It got quite vindictive in some of its early stages, and at some point I started feeling like the lyrics were becoming too melodramatic. I realized that the way to save it was to bring it back to talking about me, and that maybe I’m an unavailable person— maybe it’s me that’s unavailable. That whole thing in the song about just drifting from town to town and not really being able to fit in takes the blame off somebody else and places it on myself.

GW Your ability to question your own motives sounds like a therapist’s dream come true. How did you sustain such honesty on the album?

CLAPTON Working with a partner makes that possible—especially if it’s someone who knows what you’re up to. If Simon thought I was being dishonest with my lyrics, he would call me out and say, “I think this is unfair,” and I’d listen and address it. On that level, our partnership is as fruitful as anything I’ve ever experienced.

GW Your guitar playing is somewhat subdued on this album, but one track where you really let it rip is “Sick and Tired.” The song is built on a Texas-style shuffle rhythm, à la Stevie Ray Vaughan, and the vocal and solo are very much in the style of Jimmie Vaughan. Is this a tribute to the brothers?

CLAPTON “Sick and Tired” was done purely for fun. The riff came first, and I just thought of the Vaughan brothers. I told Simon to program a shuffle and exaggerate the backbeat so it would sound like a Texas-style groove. I then began improvising these silly lyrics, and thought, “Well, I might as well make it a song now.” It’s like a spoof, really.

GW I’m not sure how you may take this, but we thought the vocals and playing on “Sick and Tired” sound more impassioned than any performance on your blues tribute, From the Cradle [Reprise, 1994].

CLAPTON Funnily enough, I think that the bit of irony in there gave me the license to carry the anger of the vocal. I remember going into the studio and singing that with a lot of anger. Quite hard. But since there was irony in the lyrics, that made it okay. It didn’t get overindulgent.

GW You weren’t operating under the pressure of making a grand blues “statement,” as you possibly were when you recorded From the Cradle.

CLAPTON Exactly.

GW Are you particularly close to Jimmie Vaughan?

CLAPTON I’ve known Jimmie for a pretty long time. And then with the passing of his brother, Stevie, Jimmie and I kind of bonded on a very deep level. We don’t talk enough, and a lot of the time it’s my fault, but when we get together I love him. He’s as close as I’ll get to having a brother. And I think the world of his playing. And his singing—his singing is great!

GW What did you think of Stevie’s playing?

CLAPTON Oh, he was one of the greats. I have to tell this story: We played on the same bill on his last two gigs. On the first night, I watched his set for about half an hour, and then I had to leave because I couldn’t handle it. I was going to go on after this guy, and I just couldn’t handle it! I knew enough to know that his playing was just going to get better and better and better. His set had started, he was like two or three songs in, and I suddenly got that flash that I’d seen before so many times whenever I’d seen him play, which was that he was like a channel—one of the purest channels I’ve ever seen, where everything he sang and played flowed straight down from heaven. Almost like one of those mystic Sufi guys with one finger pointing up and one finger down. That’s what it was like to listen to. And I had to leave just to preserve some kind of sanity or confidence in myself.

GW In addition to paying tribute to your son and the Vaughan brothers, it’s clear you had someone else in mind while making this album. On several tracks you pay direct homage to R&B great Curtis Mayfield. Why Curtis?

CLAPTON Well, his last album, New World Order, came out the year I was starting to put this album together, and it was a huge inspiration to me. It was great on so many levels.

First, Curtis is older than me, yet he was working in a very hip field. The album was very progressive and featured guys like Organized Noise, a tremendously modern, urban R&B production company. That in itself is pretty cool.

But what really got me was that he had recently been severely crippled in a terrible stage accident and should be suicidal by all accounts, yet here he was singing about joy and gratitude and life. All of those components were an inspiration to me. Whenever I began to question why I was pushing myself so hard on Pilgrim, I only had to picture Curtis.

GW Did you go back and listen to his classic albums? Some of the string arrangements on Pilgrim seem to be inspired by earlier Curtis Mayfield tracks.

CLAPTON Yeah. That was deliberate.

GW Your vocals on “Pilgrim” and “Inside of Me” are very obviously inspired by Curtis. Were you concerned about doing such a thing?

CLAPTON No, this is outright. To me, it’s more heartfelt than just saying, “Thanks, Curtis, for the inspiration,” or writing that on the record, as anyone can do. I really wanted to work at making him proud, if I could. I hope that’s how this works out.

Now, he could be pissed-off! [laughs] Or maybe he could be both—proud and pissed-off at the same time. Who knows? But I could just hear Curtis sing the opening line in “Pilgrim,” so I had to do it in his voice. [sings] “How do I choose, and where do I draw the line between truth and necessary pain?”

There’s something kind of clever and wordy about that opening line, and I just thought, This just sounds like the sort of thing he would sing. And then I looked down and realized it was a good line, but that it didn’t really make any sense—it doesn’t mean a damn thing! [laughs] But it didn’t matter.

GW You’re right, because it sounds so righteous!

CLAPTON That’s the point. As long as it sounds righteous.

GW Do you ever fear that you’ve crossed the line separating homage and plagiarism?

CLAPTON I think it comes down to motive. I think if my motives, to put it simply, are good, then I would use that as a license to go ahead. If my motive is to say “thank you” to Curtis, which it was, and I hope that he not only hears it but also feels proud that there’s someone around who’s been that deeply moved that they just want to sing like him, I believe that’s good.

But if my motive was, Well, he just had a hit with that sound, now maybe if I imitate him, I’ll have a hit, too, that needs some examining.

GW Given your reputation as a blues scholar, part of you must really enjoy being a student.

CLAPTON It’s definitely in my nature.

GW Then you’ve certainly been true to your nature, playing R&B over the last few years. Besides studying the music of Curtis Mayfield, you’ve worked with Babyface and Tony Rich, both of whom are in the forefront of modern R&B. It sounds to me like you actually took time out to learn something new, a necessary condition for the growth of any artist.

CLAPTON You’re absolutely right. Between recording and touring, From the Cradle was a three-year project. All I did during that period was play and explore various forms of the blues. And when I stopped, I looked around and discovered that the world had changed at an astonishing rate. I couldn’t make sense of anything. I hadn’t been listening to the radio, and I had only really been stocking up what I needed to keep this blues thing up in the air.

The only thing I could latch onto was contemporary R&B, because it has its roots in blues. It became a safe place for me, hanging on with one hand and poking other things with the other. I became particularly attracted to all the different forms of dance, which still is the dominant music in England at the moment. And I had to do a lot of learning. I also made a lot of choices in the process. It was all about that difficult process of putting your finger on a stove and getting it burned—trying things out.

GW Was it particularly hard for someone of your high visibility to do?

CLAPTON It’s certainly hard to do in secret; it’s impossible. For example, as an experiment, Simon and I tried to record an album of electronic dance music anonymously, under the name TDF. We felt we had a license to explore because we were going to make music for a fashion show. And even though we were simply trying to stretch, we hit a stone wall. I was roundly criticized in England for sticking my nose in where it didn’t belong—experimenting with things like drum and bass. And so I had to back off a lot of that stuff.

GW It strikes me that you were pretty brave. Given your history, it’s hard to imagine that you would even stick your toe into that world, let alone your heart and soul. What attracted you to electronica?

CLAPTON Just some of the sounds. And I have to overcome my prejudices all the time. Don’t forget, I’m 53 years old, and this stuff is very threatening to me as a musician. It’s a bit like I’m one of the old lions, and here come the young guys. It’s almost like they would like it if I didn’t understand. They would prefer me not to understand because then I’m nothing to worry about. But the thing is, because I’ve had such a weird and varied experience with music, I can understand it and I can enjoy it.

I remember going into a club in Japan to see a specific drum-and-bass DJ. An English guy who’d had a few drinks came up to me and said, “What are you doing here?” as if to say, “You’re not supposed to like this. It’s not really cool for you to like this.” But the thing is, I do. And if I hear something I like, I want to do it. And I don’t understand this divisionist way of thinking: This is our music, that’s your music. You stay where you belong and we’ll just stay here. For me, cross-pollination has always been the lifeblood of music. And that’s what we were trying to do with that TDF thing. Some people liked it. I liked it. And you know, most important, it was the launching pad for this album, because I got to be friendly with using loops and sequences. Actually, I don’t know how to program a sequencer, but I got to the point where I wasn’t threatened by music technology, which I think is a good thing.

GW Did you use drum loops to help you write some of the songs on this album?

CLAPTON Yeah. It was random. We usually turned to technology when we ran out of things to do and needed a place to start. We would say something like, “Uh, well, um, have you heard the new Usher single?” And from there we’d just copy the drum program, dicker with it, and play along with it. That’s how the song “Pilgrim” was born: we came up with a drum program that was derived from a hit—I can’t remember which one—we changed it a little, and then I wrote the words. “Needs His Woman,” which is a song that I’ve had for about 10 years, was also built up and developed in this way.

GW While this album represents a departure for you on many levels, you still managed to include one traditional blues song: “Going Down Slow” by St. Louis Jimmie. Just who is this St. Louis Jimmie [born James Burke Oden]?

CLAPTON I don’t know much about him. I’ve never seen any photographs of him; I don’t even know what else he’s written. I’ve asked B.B. King and Jimmy Rogers about him, and though both knew him, they were sketchy with the details.

In any case, we recorded “Going Down Slow” primarily because I just wanted to include a blues, and that one has always been on my mind.

GW No doubt you’ve noticed that many important bluesmen, including Luther Allison, Jimmy Rogers and Junior Wells, have died over the past year. What do you think this means for the future of the music?

CLAPTON As long as we have their recorded work, I believe the blues are safe. For example, it could’ve been possible for me not to have any more experience of the blues than listening to albums by Robert Johnson or Muddy Waters. And even though I’ve been fortunate enough to have known many of the great bluesmen, I secured a faith in the blues even before I knew them personally, through records.

On the other hand, in terms of players coming along from that kind of experience, it’s probably the end of the road. There was something about the nature of the way these guys played and the simplicity in their approach that could only have come from a very simple way of life—a way of life that is gone.

Robert Johnson, for example, would’ve seen another musician only every now and then, let alone heard them, so his experience was so vastly different from that of musicians today. And his music must have been profoundly affected by that.

GW You heard Robert Johnson when you were only 16 years old, and it changed your life. Why do you think you connected so heavily to what was, essentially, an alien, remote music.

CLAPTON I think it has something to do with my not having a father. I sought my father in the world of the black musician, because it contained wisdom, experience, sadness and loneliness. I was not ever interested in the music of boys. From my youngest years, I was interested in the music of men.

GW And the “remote” element?

CLAPTON That would add to the appeal, wouldn’t it?

GW In a recent interview, Paul Simon was asked to name one of his contemporaries who still moved him, and he said, “How about Eric Clapton?” He went on to cite your performance on MTV Unplugged and how you used that outlet both to explore your musical past and find a direction for your future. Do you agree with that assessment?

CLAPTON When I was first putting that set together, I don’t think I had any idea where it would lead me, but I think it’s fairly accurate that I saw it as a massive opportunity to set the record straight about who I was and where I’d come from. I felt it was essential that people stop thinking about me as this one-dimensional character who should always just seriously consider getting a hold of Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker and putting Cream back together again.

I always felt that people were saying to me, Stop fucking about, man! Plug into your Marshall 100-watt and let’s get the show on the road. And I went, No deal. That’s not what I’m about. I started my career playing an acoustic guitar in a pub by myself, and this is how simple it can be, and this is how enjoyable it is on that level. That’s what Unplugged was about for me.

And it was funny, because I had my band with me, and a lot of the time I had to think of things for them to do. I could have happily just as well done it on my own. And that was important to me to state, not just for the audience at large, but for myself, as well.

GW That you were what? Not a guitar hero but a songwriter?

CLAPTON Or a journeyman. Just someone who really preferred the whole rather than one element. I think I wanted to bring people back from labeling me or trying to pigeonhole me, or getting it wrong. Just simply getting it wrong.

“I knew the spirit of the Alice Cooper group was back – what we were making was very much an album that could’ve been in the '70s”: Original Alice Cooper lineup reunites after more than 50 years – and announces brand-new album

“Such a rare piece”: Dave Navarro has chosen the guitar he’s using to record his first post-Jane’s Addiction material – and it’s a historic build

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)