Dune Rats: “We’ve been able to fine-tune our songwriting – we’re not a one-trick pony”

Album #4 might see Dune Rats put down the bongs, but they still throw one hell of a party. Australian Guitar has an invite, too – let’s make our way in…

Maturity has never been one of Dune Rats’ multitude of strengths – this is, after all, the band whose most iconic music video (for the self-titled album highlight ‘Red Light, Green Light’) was a one-take run of frontman Danny Beus and drummer BC Michaels ripping bongs. But alas, the Brisbane surf-punk trio – rounded out with bassist Brett Jansch – aren’t in their late teens and early twenties anymore, and although they haven’t shed a gram of their loveable looseness and penchant for partying, they’ve realised there’s (at least a bit) more to life than getting f***ed up and wreaking havoc.

Cue the Dunies’ game-changing fourth album, Real Rare Whale (say that five times in a row), which BC declared upon its announcement to be “a bit more of a sophisticated album”. He wasn’t lying: the ten-tracker builds on the Dunies’ well-established brand of edgy and playful punk-rock with a slew of new influences, filling out the soundscape with acoustic guitars and drum machines, a more ardent grasp on their melodic side and a willingness to experiment.

“We’ve grown up,” Beus added when the album was unveiled, “but we’re pretty fortunate that we haven’t grown apart. We’re now twelve years in, but I feel like we’re writing better tunes and finding that we’re getting to the core of who we all are, even though we’re still changing.”

Eager to learn more about how this Real Rare Whale came to life, Australian Guitar peeked behind the curtain, where Jansch was able to fill us in.

So what exactly led to Real Rare Whale being “a more sophisticated Dunies album”?

There was a bit of a talk that we had when we sort of bunkered down to write the songs. It was the height of pandemic, everyone was scared and stuff, and we didn’t want to reflect that worry of the world in our songs. We sort of had to dig deep and pull positivity out of what was a weird circumstance at that time. And I think that kind of led us to just not rely back on that ‘Scott Green’-y template – you know, going, “Chuck in a ‘f***’! chuck in a drug reference!”

And we’re all stoked that we’ve managed to do it – the album doesn’t have much swearing, and I don’t think there’s a single drug reference on it. I think in that respect, it’s more sophisticated for us. We’ve sort of been able to fine-tune our songwriting, where we can still say what we want to say, but we’re able to cut the dags off it and not cornhole Dunies into being a one-trick pony.

Did that keep the process feeling fresh or exciting for yourselves, too?

For sure. And I think that’s an important thing when you’re writing an album and you want to play the majority of it live every night – you’ve gotta back what you’ve made. We definitely back this album. You know, there’s a lot going on in the songs, both musically and lyrically. I think it’s cool for us, as we grow older, to talk about things that older people have going on in their life – but still sort of mediate that with having it not just be “old person’s music”, you know? And I think we’ve done that with this one – there’s still a lot of energy in there.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I guess ultimately, with the way that we write the songs… All three of us get together in a room, we chuck in a line each, and if a line irks us, we speak up about it. I think that’s just because we’re such close friends that we really can back it as a group, what the lyrics are about and what it all sound like. That’s a massive part of the Dunies’ vibe when we go in to record songs, too – we all go in with the same amount of gusto. It’s never like, “Ugh, I don’t want to sing this song that this dude wrote.”

This record pulls the Dunies’ sound in so many interesting directions. On the one hand, you’ve got a lot more of these big pop melodies, but you’ve also got some massive shredding. It’s like if Charli XCX had a baby with Bad Brains, it would grow up to make this album.

That’s not a bad pairing! I think that’s because we never want to go too gnarly-heavy on the music, because ultimately, we want to play it live and have it sound right. Our strength is that we can go pretty heavy on vocals – especially with the call-and-response that BC and I can do when Danny’s got a lead line – and that’s why it goes and turns into the sort of beast that it is. Even when we were recording it, we were thinking of new ways to kind of evolve with that.

We even recorded it in a different way to any album before, where each day we would just record an entire song. In the past, you know, one of us would clock in and do a week’s worth of tracking, and then we’d sit back on the couch and sort of tune out and lose interest. But this was a way to really just keep us all in the pocket. And by the evening of those nights, we were chucking down synthesisers and all this stuff, painting it way too thick – and we were always like, “Oh my God, where are we taking this song!?”

We’d always pull it back, but some of those moments where we were all experimenting late at night, they did actually still end up on the record. And that made it like this new version of Dunies, where there’s keyboards and horns and stuff in the fabric of the music.

Do you still have those demos where you took it way too far?

I do have a couple of them, and they’re like... I’m not throwing any shade on The Galvatrons, but that’s the band that swings to mind – if the Galvatrons haircut was smoking a bong, that’s what the songs became during some of those late nights.

Let’s riff on the gear side – what kind of guitars were you tearing it up on in the studio for this record?

As much as I love my own P Bass, I’d always fall back on Scott’s American P Bass. There was a little bit of a knack that I’d always seem to have in the studio: I would do my stuff on a P Bass, and I’d try to play the chordal kind of things that I play live, but whenever I put them into a recording, my head just goes, “Nup, I hear out-of-tune-ness,” so I’d always fall back on that more root note-y kind of stuff. But [on this record], I’d lay down a Tele – just a really clean, crunchy Telecaster track of the same thing I did on the bass, just so we could get that chordal sort of sound more accurately.

And then Danny would come back over with his parts, which he mostly played on his Jimmy Eat World Telecaster as well – it’s a hollowbody kind of thing with P-90s. It just sort of feeds back really nicely. There was also this really old Jazzmaster with single-coils, which sounded really brittle – you know, you could really hear the strings. And then I also played an acoustic guitar in the same way I did with the Tele, just as a part of my rhythm playing on the record. I remember when we laid down the acoustic bit at the start of ‘Up’, it was like, “Oh wow, this is how the song sounds now!” You know, that really did add an extra little zazz to it, which was pretty cool.

Ellie Robinson is an Australian writer, editor and dog enthusiast with a keen ear for pop-rock and a keen tongue for actual Pop Rocks. Her bylines include music rag staples like NME, BLUNT, Mixdown and, of course, Australian Guitar (where she also serves as Editor-at-Large), but also less expected fare like TV Soap and Snowboarding Australia. Her go-to guitar is a Fender Player Tele, which, controversially, she only picked up after she'd joined the team at Australian Guitar. Before then, Ellie was a keyboardist – thankfully, the AG crew helped her see the light…

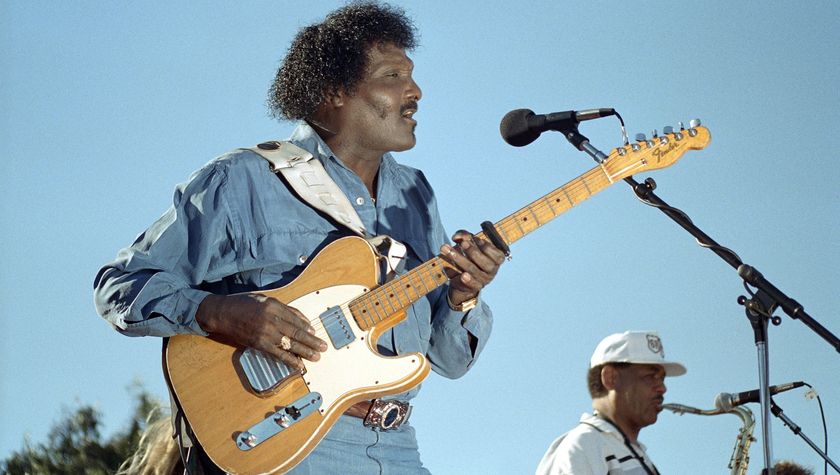

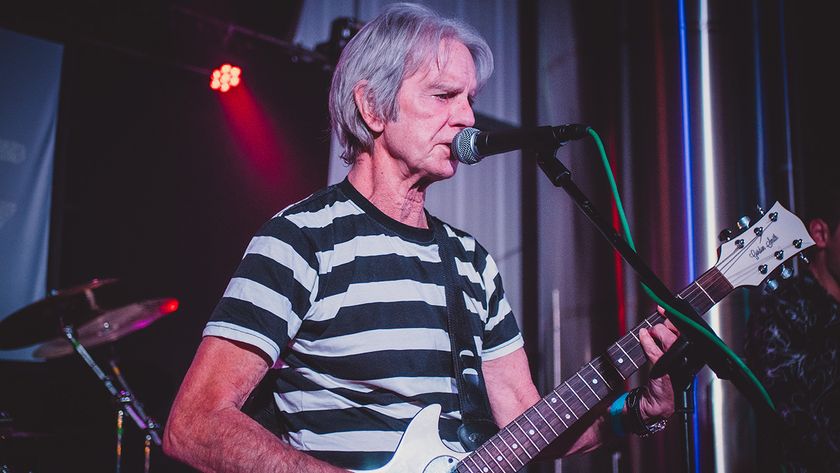

“I get asked, ‘What’s it like being a one-hit wonder?’ I say, ‘It’s better than being a no-hit wonder!’” The Vapors’ hit Turning Japanese was born at 4AM, but came to life when two guitarists were stuck into the same booth

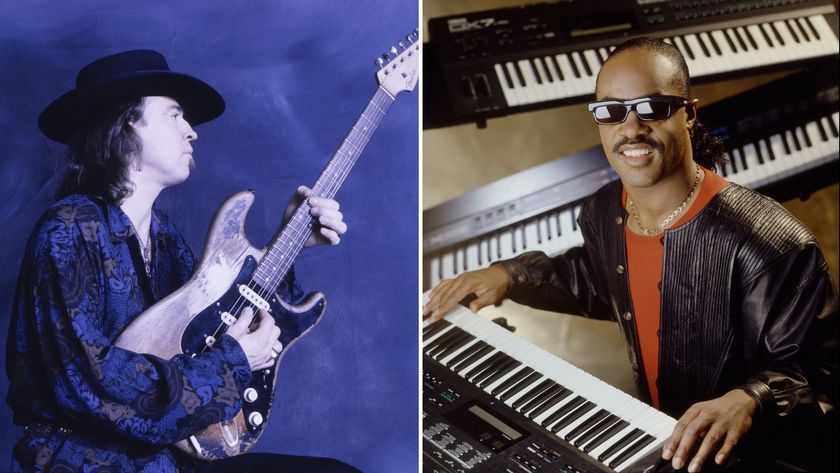

“Let's play... you start it off now, Stevie”: That time Stevie Wonder jammed with Stevie Ray Vaughan... and played SRV's number one Strat

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)