“You have to have your own sound, do it with authority and let it all hang out… If you do that you communicate with your guitar”: Duane Eddy reflects on his signature sound, hanging with Elvis and the story behind his go-to Gretsch

In this 2018 interview, available online for the first time, Eddy discusses the lessons learned as one of the founders of rock ‘n’ roll guitar

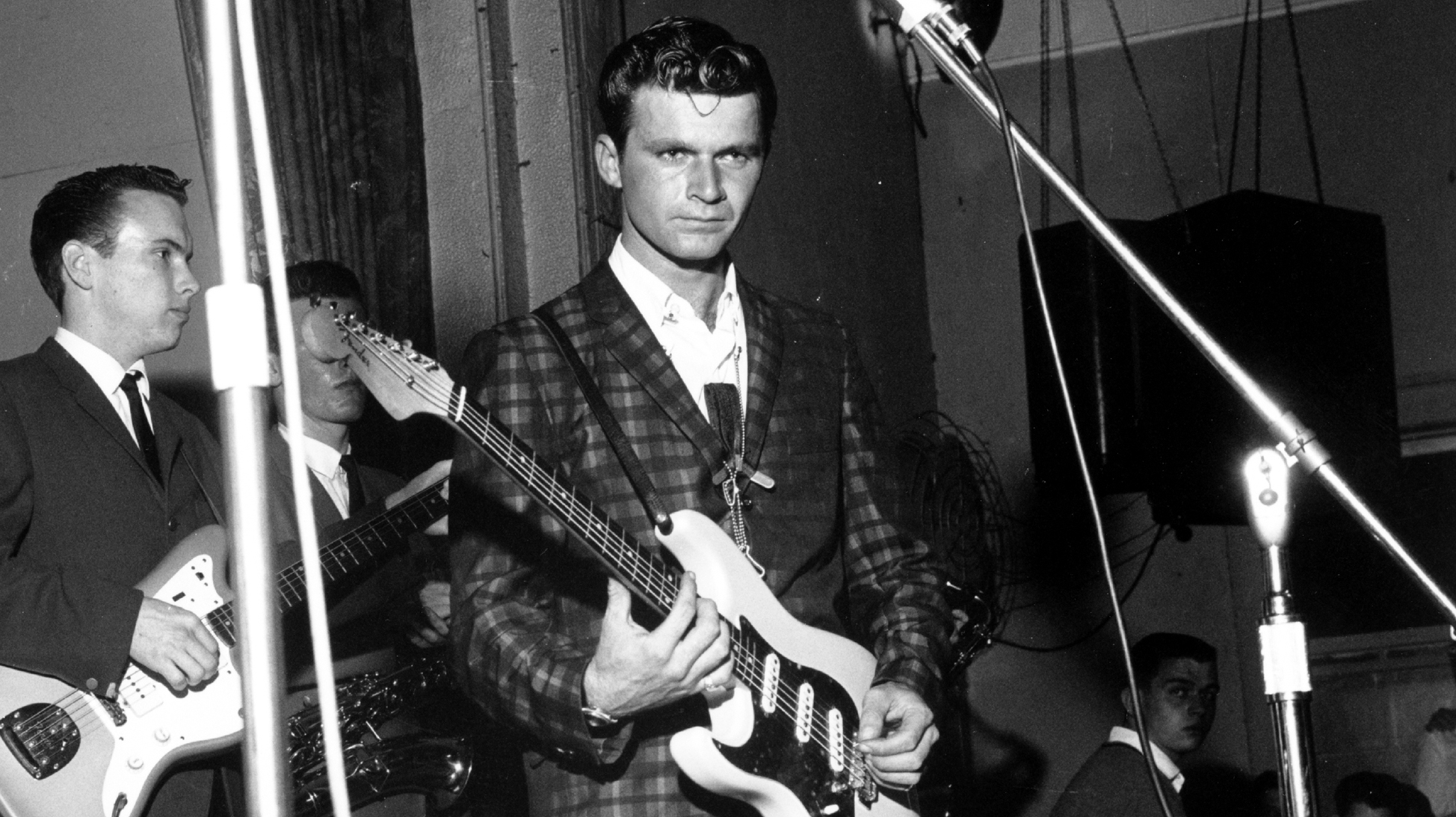

Yesterday (May 1) we got the sad news that electric guitar icon Daune Eddy had passed away. I interviewed Eddy in 2018, the year of his 80th birthday, for Total Guitar and found him to be sharp-minded, genial, and still completely driven by the thought of making music.

That piece has never been published online before, so while I’m sad about the reasons for doing so, I’m pleased to be able to share this collection of Eddy’s instrumental insight, wit and humility that I got to experience in my conversation with a monumental and truly pioneering player.

RIP Duane Eddy…

Dan Auerbach puts it best. “The thing about Duane is that he sounds like Duane,” he told Total Guitar in 2017 after first collaborating with his fellow Nashville resident.

“I mean, think about that. Think about how many fucking guitar players there are in the world. Everybody pretty much sounds the same. To be able to have your own sound is so crazy. And he did it. And he still does it.”

Go listen to any one of Eddy’s records and you’ll hear a guitarist that can carry a song by his sheer force of personality. Rebel Rouser, Cannonball, Moovin’ ’N’ Groovin’, Ramrod, his earth-shaking cover of Peter Gunn – or, for TG’s money, the vicious Stalkin’ – the list goes on… on any track you’ll hear the rib-rattling tone and stripped-down playing of his famous Gretsch-powered ’twangy’ low-end sound.

Between 1958 and 1963 Eddy sold 12 million records, all instrumentals. Nowadays that number is over 100 million. Along the way he influenced The Beatles (who would hang around outside his hotel when he played Liverpool in the early ’60s), made a fan of Elvis, helped invent surf rock and became a peer to the likes of Eddie Cochran, Chet Atkins and Buddy Holly.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As he celebrates his 80th year, we pick the brain of the man behind the twang for his essential advice to guitar players…

Find your own voice…

Wherever it may come from

“I learned to play by playing along to country records on the radio. Besides listening to guitar players, I listened to singers. Hank Williams in particular was like a mentor in that he let it all hang out. When he sang, he just touched your heart. I sang myself when I was a teenager, but I realized that I was contributing more by playing than singing.

Somebody asked me once, ‘What was your great contribution to the music business?’ And I said, ‘Not singing!’

“Somebody asked me once, ‘What was your great contribution to the music business?’ And I said, ‘Not singing!’ But when I went in to record, I knew I had to have my own sound, the same as all the country singers.

“I could tell you which country singer was about to sing, just by hearing the intro to the record, even if I’d never heard it and it was a brand new record because they all had their own instrumental style. When the singer started, sure enough, it would be someone you knew. I’d processed all that and I thought it was quite clever, actually.”

Let it all hang out

Find a way to communicate

“You have to have your own sound, do it with authority and let it all hang out. Those three things. You put the emotion into it and, as the country artists did, you do it with authority, whether you’re right or wrong and just lay it out there! Just believe it yourself, you know? If you do that you communicate with your guitar.

“That’s what all the good artists do: they communicate to people. Whether you’re a singer or writer or player or actor or a painter – communicate. Leonardo Da Vinci communicated to people, to a lot of people, with his pictures. Rembrandt is another one.

“All of those famous painters. That’s just a basic principle, if you will, of art itself. There’s a lot of great painters, a lot of great singers, a lot of great players who never get heard because they just don’t communicate with what they’re doing. They’re very skilful but something is missing.”

Remember those who are good to you

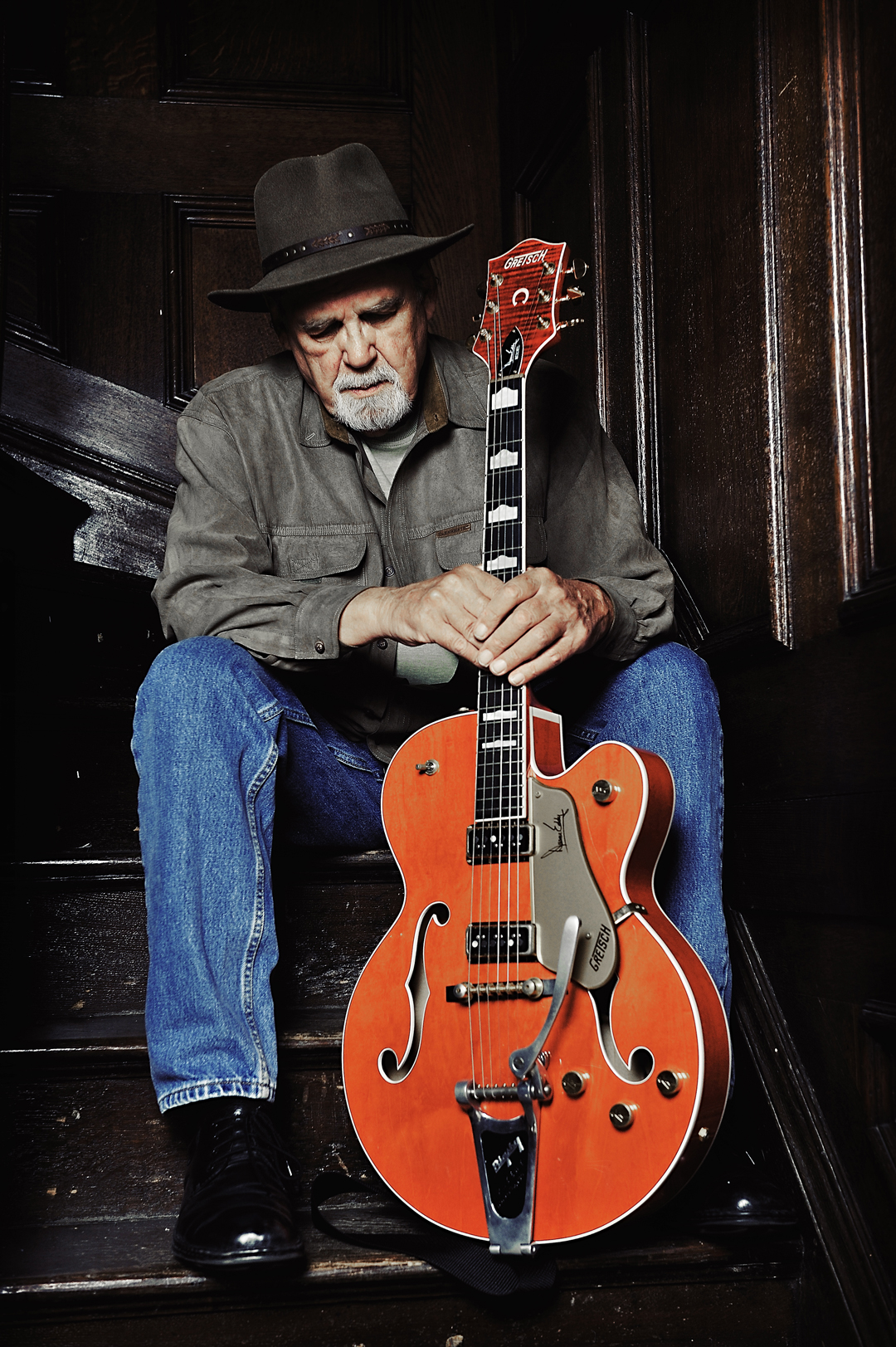

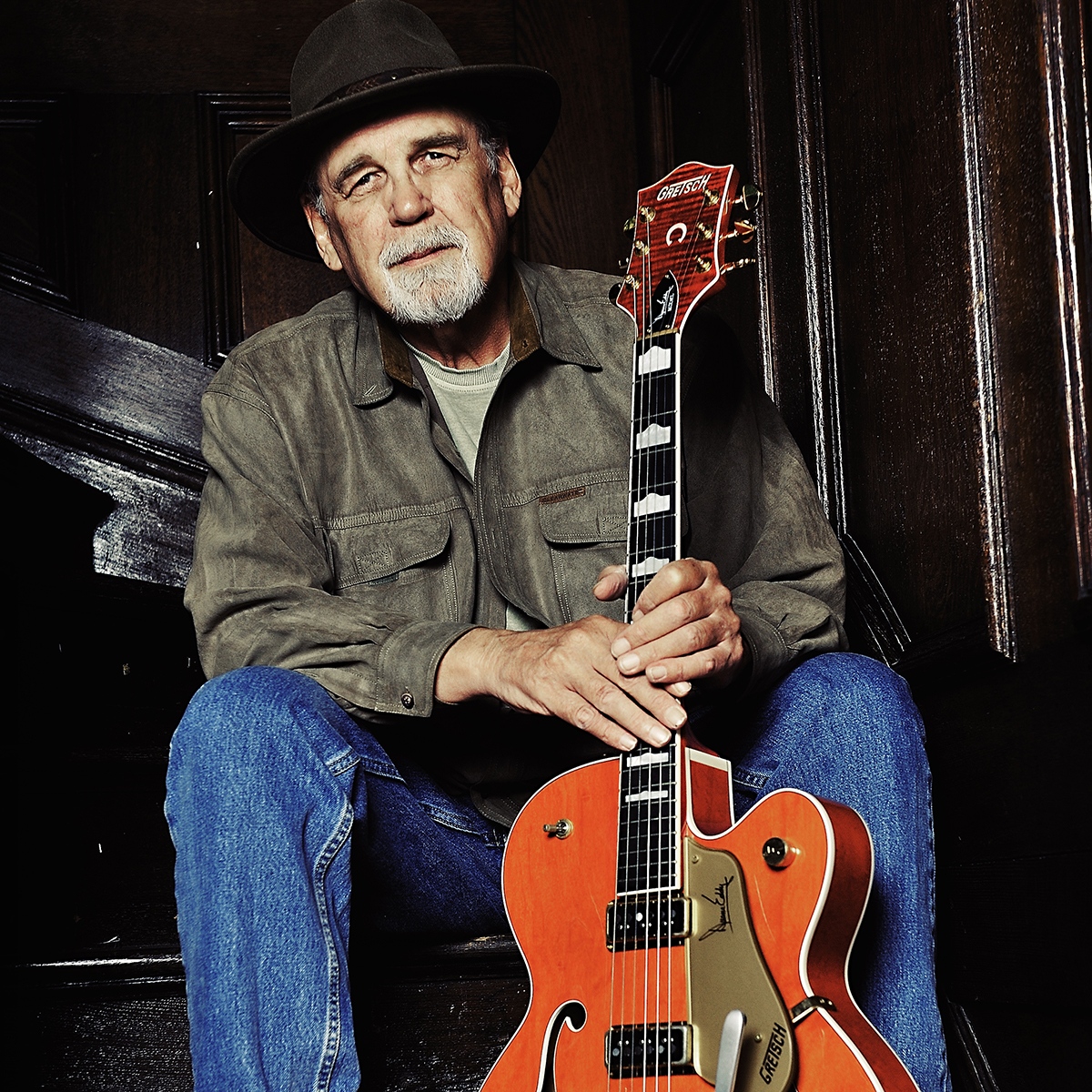

How Duane became a Gretsch player

Everybody who’s played my Gretsch has commented on how great the neck is. Buddy Holly loved it. Chuck Berry loved it

“The first Gretsch I got from Ziggy’s Music Store [in Arizona]. It had a vibrato on it and that’s why I wanted a new guitar. I had a Les Paul gold top ’54 and I wanted to do what Merle Travis did and have the vibrato. I walked in in spring 1957 and I was looking at a White Falcon on the wall, but it was almost $800, and that was a fortune in those days [approx $7,084, allowing for inflation].

“Ziggy said, ‘Well, I’ve got something you might like…’ He pulled this case out, opened it up and handed me this Orange 6120 Gretsch and it just nestled in there so sweetly and it had the nicest neck I’ve ever played.

“I started packing up my Gibson after looking at this wonderful Gretsch and Ziggy said, ‘What are you doing? Don’t you want to take the Gretsch with you?’ I said, ‘Could I!?’ He said, ‘Sure. Leave the Gibson. Take the Gretsch.’

“My dad didn’t get in for a couple of months to sign the paper work and Ziggy never said a word. He was truly the musicians’ friend. Everybody who’s played it since has commented on how great the neck is. Buddy Holly loved it. Chuck Berry loved it. Everybody who tried that guitar said, ‘Oh boy, great neck on it.’”

Keep it simple, stupid

‘Less is more’ was basically invented by Duane

“When I recorded with my 6120, that became my sound, along with a modified amp I had in those days, with a JBL speaker and 100-watts and a DeArmond tremolo. That was my rig. I did not use the tremolo on Moovin’ ’N’ Groovin’. I did use it on Rebel Rouser and Stalkin’ and Cannonball. I did not use it on Ramrod.

“It was just what felt right to me and sounded and recorded right. With my style, of keeping it simple and meaningful, as I thought of it, I couldn’t play a lot of fast notes, they’d get jumbled up.

“Because that sound was so in your face, if you turned the highs up and make it more mellow, you could play a lot of fast stuff and it doesn’t jumble up so much, but when I tried to do it with my sound, if you make one mistake it’s glaring!

“I tried to do a fancy lick one day and Lee Hazlewood my producer said, ‘Erm, you might want to come in and listen to this…’ I did and it was just a jumble and it didn’t translate on my guitar [so I stripped it out] and it came out sounding better.”

Find the gap

Why Duane hit the low-end

I worked on a few sessions and I realized whenever I got to play lead or a fill that the bass notes on the guitar were much more powerful than the high notes

“I developed the style because of what little recording I had done in Phoenix, Arizona. I worked on a few sessions and I realized whenever I got to play lead or a fill that the bass notes on the guitar were much more powerful than the high notes.

“Also, on all the early rock ’n’ roll records, I was getting sick of the high notes going ‘Dndndndn’ and playing the same thing over and over again, you know? They’d do the same licks over and over, which they’d gotten off a Bill Haley record or Les Paul, but they weren’t as good. I wanted to sound different and the bass strings were more powerful. The first record I made, I thought, ‘Well, I’ll try both.’

“So I did Moovin’ ’N’ Groovin’, which has a high part to start with and then it goes down to the low notes – very basic, very simple. But that record reached out and touched a lot of players in California and The Surfaris said that record inspired them to start surf music. If I’d known that I’d have never done it! Bad-dum-bum! Naw, I’m kidding. I thought that was amazing.”

Soundtrack your mental imagery

Can you play what you picture?

When I wrote Rebel Rouser, I pictured a gang walking toward me down a dark alley, with their knives, their switchblades and chains

“I wrote Rebel Rouser at the [second] session. With that I had a mental picture. I’d worked a rock ’n’ roll show, after doing Moovin’ ’N’ Groovin’, for a week in LA and I realized it would be cool to have something to get me onstage. I could picture the spotlight hitting me and just playing by myself or walking on playing and having the band come in.

“I also pictured a gang walking toward me down a dark alley, with their knives, their switchblades and chains. I wanted to put a bridge in it but I couldn’t figure it out, so I thought, ‘Ah, to heck with that. I’ll just modulate and do the same thing again!’”

Work hard. And quickly...

Why you should embrace pressure in the studio

“I always thought that working under pressure was good. That inspires you to get it done and you take bigger leaps, mentally. Working under pressure with time is a big help. If you’re going to take time, take the time at home to write and come up with ideas, before you get in the studio with the cash register running.

“Dan Auerbach from The Black Keys has his own studio here in Nashville and he hires musicians and records. He has the best equipment, a great engineer and a great studio. He works very hard at getting the right take and he does have all the time in the world and all of the money, but he doesn’t spend all of his money on it and he doesn’t spend all of his time on it. He just goes in there and works very hard, very quickly and comes out with great records. He is concerned about the feeling on the record. That’s what we were thinking about [back then].”

De-compress

Don’t use tech, use your ears

“One thing I hate is compression. A lot of times I don’t like playing on other people’s records because I know they’re going to put compression on my guitar, which destroys the sound of it.

Elvis said, ‘Duane Eddy: you’re too much!’ I wish I had a video of that, because he did the whole swinging thing with his arm and mimed the guitar as he said it!

“Phil Everly and I did a record which we haven’t released. He wanted me to get it out there some day. My producer friend mixed it in a state-of-the-art studio and Phil harmonised with himself. But when I went in to listen to it, it just sounded like two guys singing and one guy playing guitar... there was nothing distinctive about it.

“I asked, ‘Have you got compression on this?’ And they smiled and nodded. And I said, ‘Well can we take it all off?’ And their faces fell! ‘All of it!?’ I said, ‘Well, all of it off of Phil and all of it off of me…’ So they twiddled the knobs and there’s Phil sounding like Phil and me sounding like me. I thought, ‘I don’t care what you do with the rest of the record – compress your brains out – but leave us alone!’”

The charisma of the king

How Elvis continues to inspire

“I never considered Elvis a peer, but he considered the rest of us peers – and [when I met him in 1970] he told me he loved my records. He said, ‘Duane Eddy: you’re too much!’ I wish I had a video of that, because he did the whole swinging thing with his arm and mimed the guitar as he said it!

“He was just everything I wanted him to be. An amazing, beautiful man. He was so perfect-looking, you know? He had whatever ‘it’ was in spades. He showed me a clipping of a poll from Melody Maker and he said, ‘Look at this… I won it again. I’ve been number one every year for 15 years!’ He was proud of that, you know?

“I thought: ‘I love that he appreciates that people love him so much.’ I kind of feel the same… I’m still thinking, ‘I need to play these songs like I’m playing them for the first time.’ I’m giving it all I got, which is getting harder as I get older!”

Matt is Deputy Editor for GuitarWorld.com. Before that he spent 10 years as a freelance music journalist, interviewing artists for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.

Ozzy Osbourne’s solo band has long been a proving ground for metal’s most outstanding players. From Randy Rhoads to Zakk Wylde, via Brad Gillis and Gus G, here are all the players – and nearly players – in the Osbourne saga

“I could be blazing on Instagram, and there'll still be comments like, ‘You'll never be Richie’”: The recent Bon Jovi documentary helped guitarist Phil X win over even more of the band's fans – but he still deals with some naysayers