The story of Africa’s guitar god Dr. Nico, the Congolese innovator admired by Jimi Hendrix

By the time ‘Clapton is God’ graffiti was appearing on London walls, Africa had found a new deity of guitar, and his name was Nicolas Kasanda wa Mikalay

When Jimi Hendrix passed through Paris on one of his tours, a guitarist he was keen to meet was Nicolas Kasanda wa Mikalay – the Congolese fingerpicking electric guitar master more widely known as Dr. Nico, or to many across mid-20th century Africa, L’ Eternel Docteur Nico. At around the same time that “Clapton is God” graffiti was appearing on London walls, Africans were calling Dr. Nico the Guitar God.

With good reason. If cascades of gorgeous-to-gritty tone, an effortless flow of sparkling, playful melody, harmonization and dazzling polyrhythmic syncopations make up your idea of six-string divinity, Dr. Nico surely belongs in your pantheon. He came along at an ideal moment in musical history and African history.

In the late 1950s and early '60s, the electric guitar had reached a golden age in its evolution as a musical instrument. As a result, the world went mad for electric guitars. In Africa, Dr. Nico was one of the key players who established a prominent place for the electric guitar in the popular music of the continent. In 1960, his native country – what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo – won its freedom from Belgian colonial rule. The people were ready to celebrate their liberation.

Dr. Nico helped forge the soundtrack for that party, initially as a guitarist for Le Grand Kalle et l’African Jazz, called the first great Congolese band. He was only 14 when he first joined Kalle in 1953, and played lead guitar on the group’s iconic 1960 single, Independence Cha Cha.

Often credited as the first pan-African hit record, the song helped popularize Congolese rumba – a style of dance music adapted from Cuban son and other Latin musical idioms.

One thing that distinguished Congolese rumba from its Latin-Caribbean counterparts is that electric guitars took on some of the musical roles played by horns, woodwinds, pianos and other instruments in Cuban music.

You can draw a parallel to Charlie Christian’s work with Benny Goodman in the late '30s and early '40s – using the then-new tonalities of the electric guitar to play solos and other parts more traditionally played by saxes, trumpets and the like. What Charlie Christian is to American jazz guitar, Dr. Nico is to Africa’s vibrant guitar legacy – an originator and innovator.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

He played a major role in the creation of the unique, three-guitar style heard in Congolese rumba and subsequent genres such as soukous. Whereas rock, country and other American styles typically have two guitars – lead and rhythm – African dance music also adds a third guitar, playing what’s known as mi-solo, or “half solo.”

While the rhythm guitar takes care of chording and comping, the mi-solo guitar often plays syncopated ostinatos known as guajeos, which are based around the song’s harmonic progression. Guajeos are heard throughout Latin and Afro-Caribbean popular music. In salsa, to cite a familiar example, guajeos are typically played in octaves by a pianist. But in Congolese pop, the role often falls to the electric mi-solo guitar.

Which leaves the lead guitar free to dance atop the swirling rhythmic maze created by the two other guitars, along with percussion, horns and other instruments. And this top line is where Dr. Nico’s mastery shines through.

The fecundity of his melodic imagination seems limitless at times – non-stop flurries of fluid arpeggios, double-stop harmonizations, rhythmic punctuations accentuating the plaintive, three-part male vocal harmonies of Congolese rumba, and taking center stage when the time for a solo rolls around. Which is a frequent occurrence in this style of music.

As with all dance music, it’s about generating and maintaining momentum – building up, breaking down, drawing dancers and listeners deeper and deeper into the groove.

Actually, Dr. Nico is one of two great Congolese guitar originators. The other is Franco Luambo Makiadi, leader of the group TPOK Jazz. Both were boldly innovative and much-imitated stylists – the Hendrix and Clapton of their time and place. But where Franco was a bit more geared toward using the electric guitar to emulate traditional African instruments, Dr. Nico dove head-first into the fuzzy, tremoloed-out, mid-century modernism of the electric guitar.

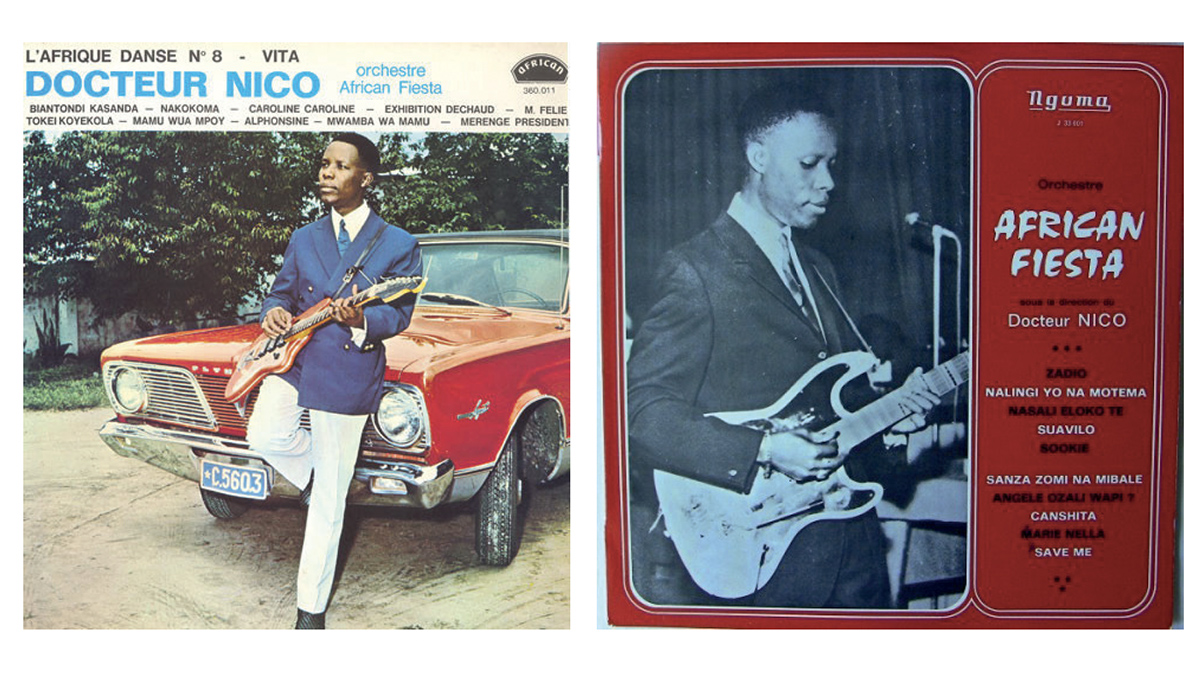

There’s a well known photo of Dr. Nico stylishly dressed in a blue blazer and tie, white shirt and trousers, leaning on the front grille of bright red 1965 Plymouth Barracuda and holding a Egmond Typhoon electric guitar – a cheap Dutch import – in a matching shade of red.

Other photos show him with a blond German archtop and a white Hofner solidbody. None of these are great guitars, obviously, but Dr. Nico embraced their lo-fi tonalities to create a wild and beguiling range of guitar timbres. He’s known for introducing things like tremolo and reverb into African guitar music.

There’s a kind of grainy, rough-edged poetry to the sound – a throbbing, murky miasma – that both complements and contrasts with L’Eternel Docteur’s supple execution. A good example would be a track like Toye na sango by L’African Fiesta, a group he formed in 1963 after leaving Le Grand Kalle.

With the gnarly harmonic overtones produced by cheap gear, Nico’s guitar sometimes sounds like a steel drum or marimba. At the other end of the spectrum, he could bring the glistening glissandos of Hawaiian and country music to a ballad like Pauline, also by L’African Fiesta. He was truly international in scope.

Which was somewhat the point. Congolese rumba became the music of the rising middle class in the newly liberated African nation that had changed its name from the Belgian Congo to the Republic of Congo in 1960 – a country now taking its place on the international stage.

The photo of Dr. Nico with the big American muscle car, snazzy suit and red guitar sums up the aspirational mood of that milieu. (Note, incidentally, that the color scheme is red, white and blue.)

In the middle years of the 20th century, Latin music and dance crazes had become popular worldwide. Artists like the Cuban pianist Perez Prado were topping the charts in America, the UK and elsewhere. Dr. Nico had visited Cuba in the Fifties, absorbing the music firsthand.

For African musicians like Dr. Nico, the embrace of Latin rhythms represented a repatriation of sorts. Many of those rhythms had originated in Africa, brought to the New World by the slave trade. It couldn’t have been more timely to bring them back home to a nation that had newly achieved independence from European colonial rule.

But the mid-century African musicians put their own twist on Latin rhythms. There’s a gentle rhythmic lilt to Congolese rumba that’s unlike anything from the other side of the Atlantic. This was enhanced by poetic lyrics in French (the language of the Belgian colonizers) and Lingala, one of the region’s indigenous languages. And of course, there are those guitars – an undulating rhythmic labyrinth that’s easy to get lost in.

L’African Fiesta’s lineup fluctuated. Nico’s brother Mwamba Dechaud was sometimes his co-guitarist. And by 1965 the group had morphed into African Fiesta Sukisa. Dr. Nico was said to be “difficult” to get along with, and a poor businessman. He left the music industry in the mid Seventies, following the collapse of his Belgian record label. He died in Belgium in 1985.

Just as he was leaving this earth, America was waking up to the splendor of African guitar music through the work of Nigerian band leader King Sunny Ade, who gained international exposure after signing with Island Records in 1982.

Label chief Chris Blackwell was touting him as “the next Bob Marley”. Paul Simon brought South African music to the worldwide mainstream with his multi-platinum Graceland album in 1986, which helped focus some much-deserved attention on South African guitarist Ray Phiri.

With these inspirations, guitar players in America and Europe began exploring African music. Today you can find video tutorials for pieces like “Independence Cha Cha” on YouTube. If you’re a rock, blues, country, funk or folk guitarist in a rhythmic rut, Congolese rumba has the power to set you free.

In the '70s and '80s, the Congolese rumba music of Dr. Nico and his contemporaries became the basis for soukous, which would foster phenomenal guitarists like Diblo Dibala – known as “Machine Gun” for the rapid-fire accuracy of his playing.

Soukous, in turn, spawned the stylish dance genres kwasa kwasa and zouk. Beyond this, rhythmically interlocking electric guitar patterns have become integral to so many musical styles all across Africa, from Tuareg bands and artists like Tinarawen and Mdou Moctar in the North to mbanqua groups like the Makgona Tsohle Band from South Africa.

In the vast continent of African electric guitar music, all roads ultimately lead back to Dr. Nico.

- Thanks to Michael Newton for help in identifying some of Dr. Nico’s guitars – AdP

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

“It combines unique aesthetics with modern playability and impressive tone, creating a Firebird unlike any I’ve had the pleasure of playing before”: Gibson Firebird Platypus review

“I met Joe when he was 12. He picked up a vintage guitar in one store and they told him to leave. But someone said, ‘This guy called Norm will let you play his stuff’”: The unlikely rise of Norman’s Rare Guitars and the birth of the vintage guitar market