Denny Tedesco Discusses His New Film, 'The Wrecking Crew,' an Ode to Pop's Elite Studio Musicians

Filmmaker Denny Tedesco remembers riding his bike to grade school with a transistor radio tied to the handlebars. Memories like that one are easily triggered when he hears songs from his childhood.

“To this day, certain songs hit me and I remember,” he says. “I remember where I was. Music is under-appreciated as a sense. It’s hearing, but it brings back taste, smell, everything. It puts you in a space.”

Tedesco grew up around music. His father, guitarist Tommy Tedesco, was one of the best-known session players and teachers to come out of the West Coast studio world, where an elite group of musicians defined the sound of countless 1960s and 1970s hit records by a who’s who of artists ranging from Frank Sinatra to the Beach Boys.

When Tommy Tedesco was diagnosed with cancer, Denny undertook a tremendous goal: a documentary about those session musicians that would tell their story through their words, and those of the producers and artists they worked with. In 1996, he began working on the film, which he titled The Wrecking Crew after the name drummer Hal Blaine later used in reference to the musicians.

With help from Emmy-winning editor and producer Claire Scanlon, he completed the movie in 2008 and entered it into several film festivals. Two years later, the International Documentary Association became a fiscal sponsor. A Kickstarter project was successfully funded in December 2013 to license the remaining songs and stock footage and compensate the musicians via the American Federation of Musicians.

The Wrecking Crew is on a limited run in U.S. theaters and available as a digital download, VOD and on DVD.

GUITAR WORLD: What is the key to making a good documentary? For musicians, a subject like this one is fascinating no matter what, but for the general music fan, you have to hold their interest in a world of soundbite attention spans.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I think that’s why it hits on different levels. Musicians — piece of cake — they understand it and see themselves. The music, 50 percent of the film is music, and everybody knows that music. Then there are people who have lost a parent, or both parents, and they will understand why I wanted to make this movie.

Many of the songs these musicians recorded were considered pop — popular. When did pop become a dirty word in the industry?

That’s a hell of a question! How can I put this? There are so many different things I can go off on. The business was different. My father would do seminars and tell the kids, “You have music and you have the music business and sometimes they mix, but don’t expect them to mix all the time.”

Some of the music he played was trite and simplistic, it was probably pop, but pop means popular, whatever it is. I listen to artists all day with my kids and it drives me crazy, but it’s popular music. It’s a question to be debated. When we listened to stuff in the 1960s and 1970s, we had radio and albums. We didn’t listen to stuff from 1924, our parents’ stuff. Maybe we listened to the standards, but not much. Now anybody can make an album, but there is no business to support it. In those days you had people working in radio stations and playing live gigs.

I think technology made it easier for anybody to record, but it made it much harder to promote when we have so many more choices in our lives and so much information coming at us. I was bombarded by maybe six television stations. We had a phone. You got a message if someone was around to take it. Now, everybody wants it now, answer me now, Twitter it now, and that’s why it’s difficult for songs to last. Maybe a great song will stand up to “Good Vibrations” and the Beatles, but will it stand the test of time? It will be impossible for anybody to outlast them. I’m not belittling today’s musicians. It’s just a harder time.

What did you learn from your father?

My father was extremely practical and had an understanding of how to deal with people. The reason I’ve done so well in terms of getting to certain people is because he treated people extremely well. If he had a problem with someone, most likely a lot of other people did too. I’ve gone around the world and people would say, “I met your dad at a seminar,” and they’d tell me how kind he was and how very approachable. I think he just taught us to try our best to never lose patience. We all lose patience, but I try not to because it will make a difference down the road.

What surprised you the most about the musicians as you got to know them?

Not too much surprised me, other than a couple of stories here and there. They all got along fairly well. There was no backstabbing. They were very appreciative of what happened to them. There was no bitterness in any of them, and overall they were extremely grateful of where they were at the time and what happened. Looking back, they were very happy. This story is about musicians who created the greatest music but also were making a living, going to work and putting their kids through school.

You’ve had so many years of working in and around the music industry and watching it change. What do you see, both good and bad?

It’s harder and harder to make a real career in music, versus what session players did. Movie music went to different places where they don’t pay musicians the same rate, they don’t make a living the way did they did here in L.A. They’re paid to take more and more, and by the time it gets to the musicians, they make less and less and are not able to make the living they could make years ago.

Also, when I came into filmmaking, the first jobs out of college were rock videos when MTV started. It helped to sell albums, but it couldn’t have been that much because they spent a lot of money on videos. So I think a lot of people took advantage in the business. Everything was gravy for a while. There were projects where people funded singing groups with huge budgets of $350,000. In the 1960s these guys did an album a day sometimes. That’s ridiculous — $350,000 for a group? It’s wasted money, thrown away. Now people are laid off, there’s downloading — the record companies should have jumped on it and offered that right away, but they wanted to make their money. It imploded and will never recover.

The business is different. Musicians today are making records without being in a room together. Files are sent around, there’s no influencing each other, there’s nothing anyone can do to push each other in another direction because they’re not in the same room. You fix a solo in Pro Tools instead of “Let’s do it again.” Technology is amazing, but it has taken the soul out of it. Kids, especially, need to learn how to play with each other. It always helps musicians to influence and learn from each other.

My father was so much better a player when there were two more guitar players with him and they pushed him. When he did solo work, it was beautiful, but it was not my favorite because he was not being pushed in another direction. For musicians, the banter is the great thing. There is nothing like it. Musicians are comedians. They one-up and tease each other and it’s the greatest thing to be around.

To learn more about The Wrecking Crew, watch the trailer, and get information about the DVD release and screenings, visit wreckingcrewfilm.com.

Alison Richter interviews artists, producers, engineers and other music industry professionals for print and online publications. Read more of her interviews at http://www.examiner.com/music-industry-in-national/alison-richter.

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.

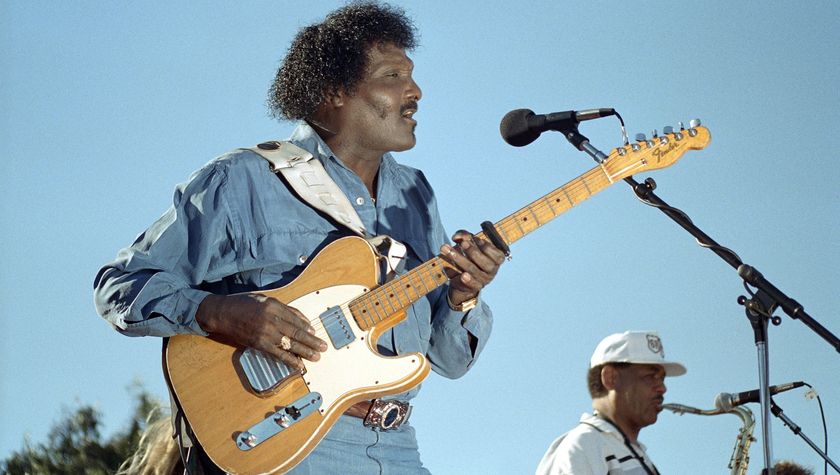

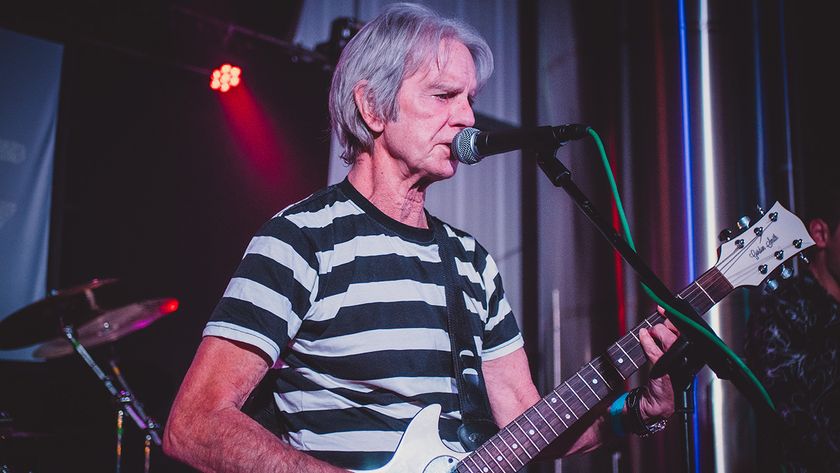

“I get asked, ‘What’s it like being a one-hit wonder?’ I say, ‘It’s better than being a no-hit wonder!’” The Vapors’ hit Turning Japanese was born at 4AM, but came to life when two guitarists were stuck into the same booth

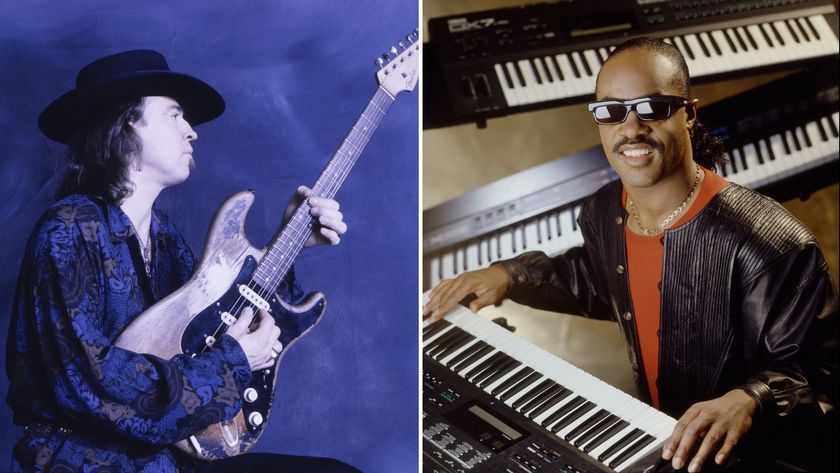

“Let's play... you start it off now, Stevie”: That time Stevie Wonder jammed with Stevie Ray Vaughan... and played SRV's number one Strat

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)