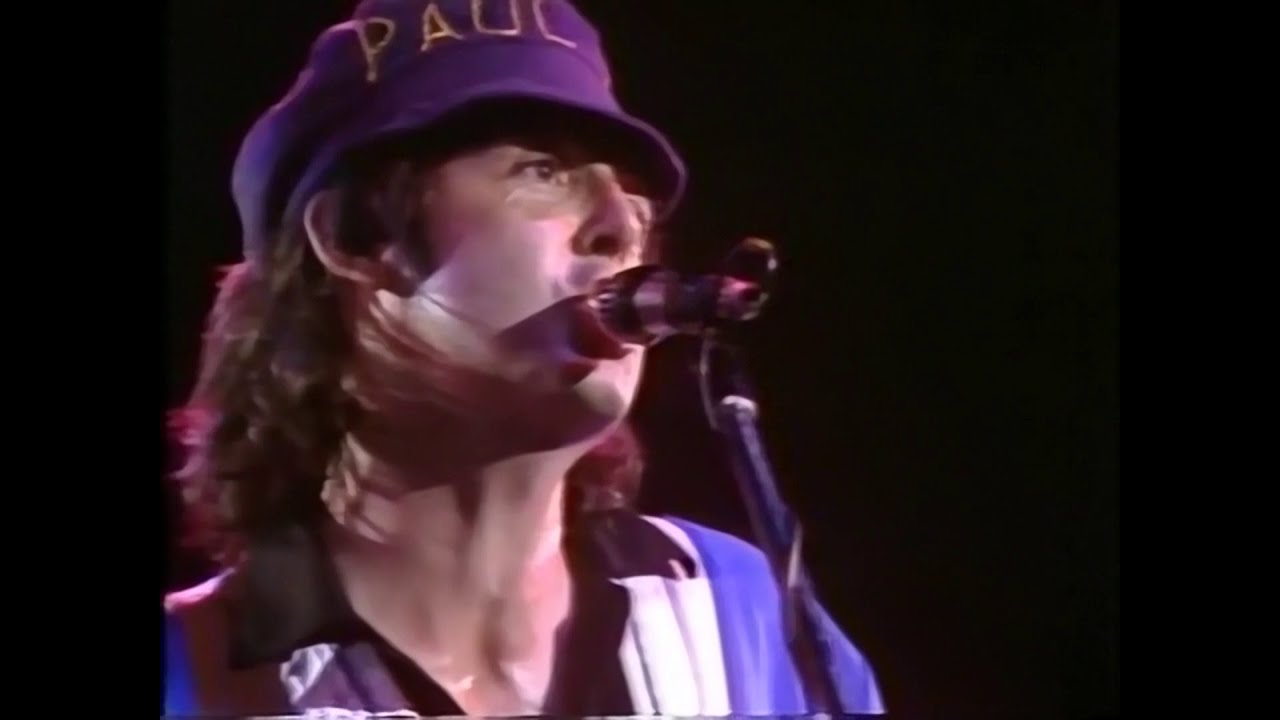

“I’m actually surprised we’re that well-remembered. I’m just a normal musician who doesn’t really think about the fame side of it”: In his final interview, Denny Laine looks back on the breakthrough success and enduring legacy of Paul McCartney and Wings

1973 was the year Paul McCartney’s ragtag group, Wings, first scored Beatles-sized success. As late guitarist Denny Laine recalled, they were no overnight success

Following news of guitarist Denny Laine’s passing on December 5 2023, we are resharing his final interview with Guitar World, which was first published in January 2023, and found the guitarist looking back on his career with Wings.

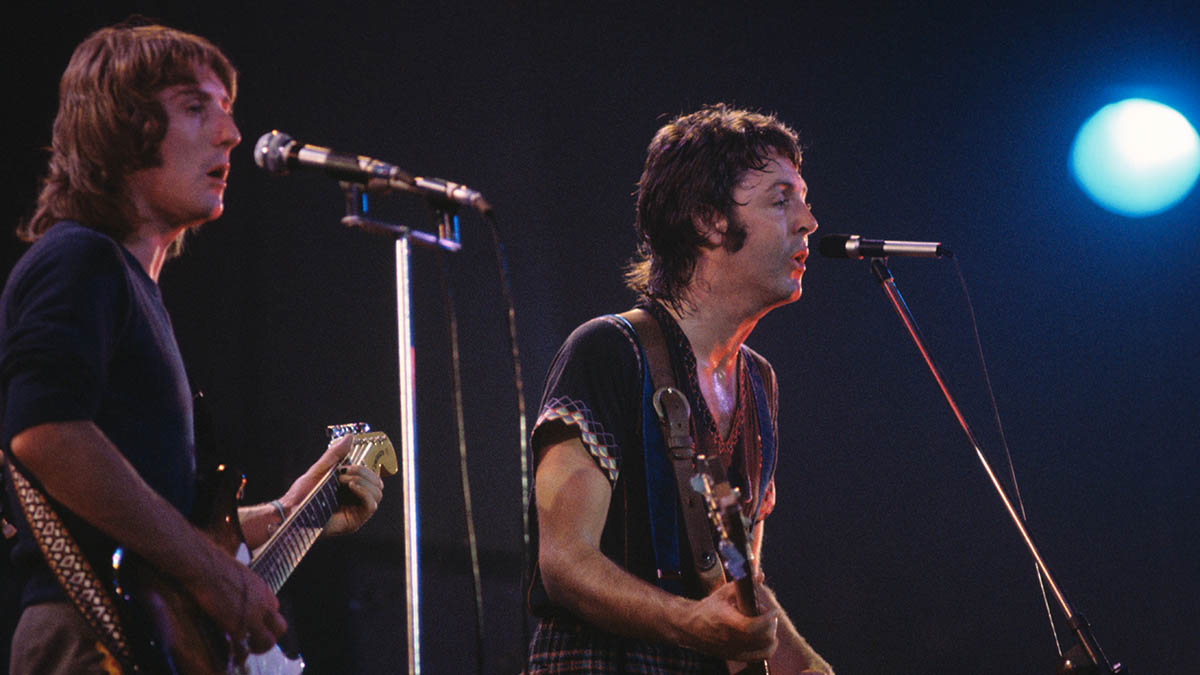

“The first lineup of Wings was my favorite one,” Denny Laine says. “Something about those players together really gelled.”

With the benefit of hindsight and critical reassessment, the early incarnation of Paul and Linda McCartney’s group – rhythm guitarist /vocalist Laine, drummer Denny Seiwell and lead guitarist Henry McCullough – really does stand out. They were, as Laine modestly puts it, “a really good rock ’n’ roll band.”

But back in 1971-72, Wings was relentlessly maligned by the press. Rolling Stone called them “flaccid” and “aimless,” wondering why they even bothered to release their debut album, 1971’s Wild Life. Linda’s presence in the group galled critics to go further, writing what McCartney called “really savage stuff” about her.

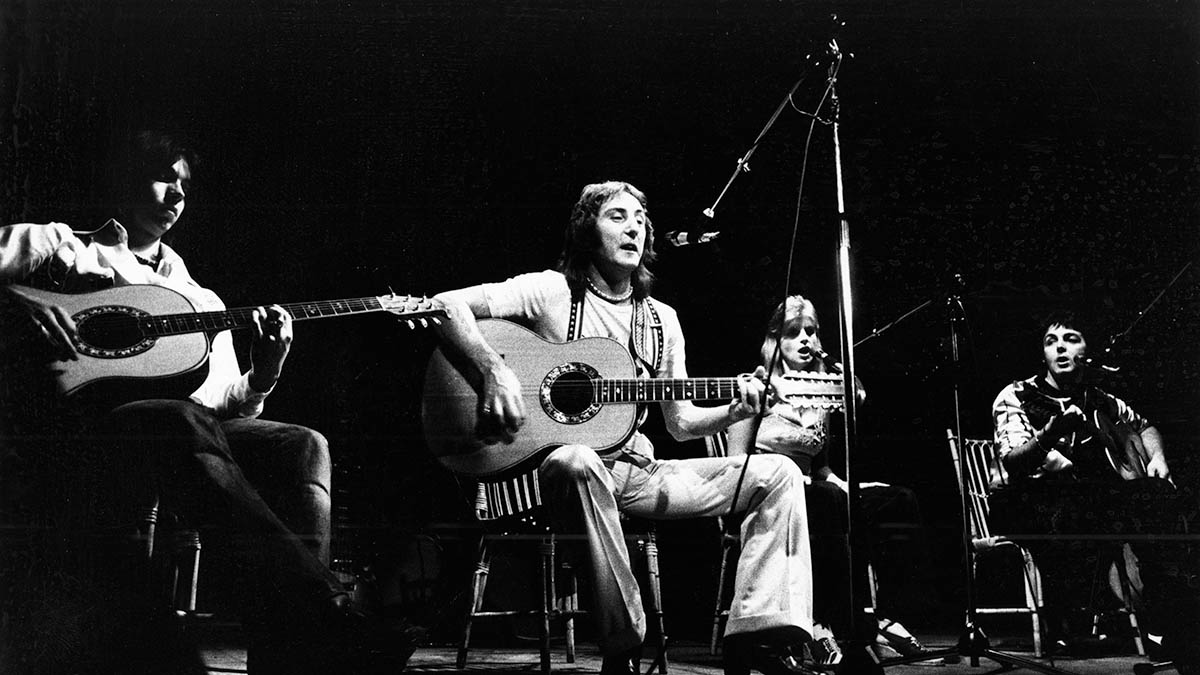

Much of this was fueled by the impossible bar raised by the Beatles. And rather than try to measure up to their legacy, Wings were willfully low-key and ramshackle, traveling in a beat-up van, turning up unannounced at colleges to play and never including any of the songs that made their leader one of the most famous musicians on the planet.

But all that changed in 1973. Red Rose Speedway came out in April. The album – re-released in 2018 as a deluxe box set – marked the beginning of McCartney putting more polish on the band’s record-making.

“We’d done more work,” Laine says, “and we were much tighter.” The album also gave Wings their first Number 1 single with My Love. Three months later, the rollicking James Bond theme Live and Let Die upped the ante even further. Nobody was laughing at Wings now. And then in December came their masterpiece, Band on the Run, made as a trio under trying circumstances in a run-down studio in Lagos, Nigeria.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Featuring Band on the Run, Let Me Roll It, Jet, Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-Five and Laine’s co-written gem No Words, it remains the band’s definitive statement. Though Laine says he “doesn’t do favorites,” the experience of making it is still a highlight of his 60-year career. “It was just the three of us, and the input I had makes it stand out as something special.”

Now 77, Laine is finishing a new album and preparing for an acoustic “Stories Behind the Songs” tour in early 2023 that will include material spanning his entire catalog – from the Moody Blues [he was a founding member of the Moodies] to Wings to his solo years.

“I can’t live without live work,” he says. “There’s no substitute for playing live and getting the feeling of connecting with an audience.”

How do you think Wings evolved in the two years from Wild Life to Red Rose Speedway?

“Wild Life was very live-sounding – really, it was kind of what we were doing in our rehearsals. We weren’t trying to make a big-time album. It was very basic and raw, and to this day, a lot of people think that gives it more credibility than they did at the time. On Red Rose Speedway, we were more rehearsed and tighter, since we’d been on the road.

“So it was the first big production that we did, using Glyn Johns as a co-producer with Paul. It was meant to be a double album, and we did record more tracks than we needed. But it never came out that way. In fact, some of those tracks have been released on other packages, and are now on the box set.”

I’ve always been the kind of person who’s stuck to one guitar. I never had five guitars on stage

What were your go-to guitars and amps on Red Rose Speedway?

“At that time, my main guitars were a Fender Telecaster semi-hollow thinline with a maple neck and a sunburst Gibson acoustic jumbo, the SJ-200. I occasionally used a Strat, too. I had loads of other guitars, but I’ve always been the kind of person who’s stuck to one guitar. I never had five guitars on stage. My main amp was a Gibson Titan. It’s the model Chuck Berry had. But I also used a Vox AC30. That’s the amp I always used in the ’60s. Everybody loved their Vox back then.”

Your rhythm parts in these songs are rarely just straight strumming. Take Big Barn Bed or the Hold Me Tight medley. There are lots of accents, held chords, rests and double-tracked arpeggiated chords. It’s very dynamic and intricate. Once you learned a song, can you describe how you’d approach the rhythm part?

“My memory of what I actually played on these things is gone. [Laughs] I can just about remember what guitar it was and that’s it. That said, if Paul writes a song on guitar, and it’s a very simple thing, I would probably just try to add to that. I wouldn’t be the main rhythm guitarist, because what the song needed was accompaniment.

“I was always pretty in with what Paul was playing, which probably makes it sound more like one part, probably. We did that a lot, where I would play lead parts in unison with him, like on Helen Wheels [from Band on the Run].

“If Paul was on piano, I’d have a bit more freedom to find my own guitar part. It was quite easy to do that with him. You have to remember – he and I grew up with the same musical tastes. We listened to all the same bits, so we have a very similar style.”

What do you remember about Henry McCullough’s classic guitar solo in My Love? Was it really as much of a surprise unveiling as Paul has said?

“I don’t know if it was a surprise. [Laughs] I played bass on that song, for a start. Like me, Paul always had an idea for what a solo should be. If I was playing it, I’d play something around the tune, you know? Paul had a part for Henry to play. And Henry said, ‘I have another idea, just leave it with me.’

“He’d obviously been sitting with it and worked out a little solo. Paul said, ‘Okay, that’s great,’ and it made the cut. It was something Paul hadn’t thought of playing. He generally sticks to the melody, whereas Henry added a bit more of a blues approach to it, which I think fitted it perfectly.”

The sessions started with Glyn Johns – whom Paul had worked with during the Beatles’ Get Back/Let It Be sessions in 1969 – co-producing, then Paul took over.

“There was a clash of some kind. I can’t really go into what the politics were, because I wasn’t involved in it. All I know is Paul likes to be his own producer. He might’ve had some experimental ideas that Glyn wasn’t willing to try. You know, putting the amps in little rooms to get certain sounds. I get it.

“I don’t really work with producers too well either. I worked with Denny Cordell in the Moody Blues days because he was a friend of mine. As far as I’m concerned, I didn’t notice any major tension on Red Rose Speedway. Glyn was just there at Olympic Studios. Then a few weeks later, he wasn’t. It was a little bit of a surprise to me.”

Even Michael Jackson asked Paul, ‘Who’s singing the harmonies there?’ ‘That’s Denny and Linda.’ There was a sound there that can’t be mimicked. It was a special part of Wings

The background vocal blend of you, Paul and Linda is a hugely underappreciated part of the Wings sound. I’m thinking of the counter-melodies and “oohs” on When the Night and Get On the Right Thing, where your three voices are so complementary that they create this fourth sound. Can you talk about how you worked out arrangements and recorded those parts?

“Linda was a very musical person, but she was not a trained professional, if you want to call it that. She hadn’t done any live or studio work. So it took longer, but she could sing in tune, and you give her an idea, she could sing it. Either Paul or me would come up with a line for her to sing. We’d just sit there and say, ‘Where do we need harmonies?’ then work out the parts. Linda took to it quite quickly.

“But that blend became very popular and part of our sound. Even Michael Jackson asked Paul, ‘Who’s singing the harmonies there?’ ‘That’s Denny and Linda.’ There was a sound there that can’t be mimicked. It was a special part of Wings and I’m quite happy about that. It was nice to see Linda learning that stuff and how well she did. Again, on stage, she wasn’t experienced and sometimes had problems. But in the studio, she was spot on.”

Were you usually three around one mic?

“Yes. Often it was just me and Linda around the mic, unless it was a thing where Paul had to throw in a lead vocal and we’d sing around it. We doubled the parts a lot. Or we used ADT, the Automatic Double Tracking that the Beatles invented at EMI. It was a little machine that could simulate doubling. We always wanted to get that bigger, lush harmony sound. Everybody does it these days, but we were kind of pioneers in all that.”

We always wanted to get that bigger, lush harmony sound. Everybody does it these days, but we were kind of pioneers in all that

For Band on the Run, what did you think when Paul and Linda decided to go to Lagos?

“I thought it was a great idea. I love going places where we’re going to be influenced by the local culture and music. Also, Ginger Baker had a studio there. We didn’t go there for that reason, but Ginger introduced us to some people, so we didn’t feel so alone [Note: Baker played percussion on Mamunia, shaking gravel in an old fire bucket]. The African drumming thing was a big influence on all of us.

“We were all into ethnic music, whether reggae or African or whatever. We sat around and looked at the map where all the EMI studios were and picked that one. ‘That sounds like it could be fun.’ Also, I think it might’ve been the only location available for when we wanted to go. I never had any negative feelings about going. I thought it was a nice change. There was a great energy there. Though we didn’t know it would be monsoon season. [Laughs]”

Denny Seiwell and Henry McCullough bailed on the trip at the last minute.

“As I say, I wasn’t involved in the politics, so I was just as surprised as anyone when they didn’t turn up [Note: Seiwell said McCartney had a falling out with McCullough over the guitarist’s refusal to play the same solos in every show]. I’ve been told that Paul had a talk with [Seiwell] the night before we went and he kind of decided he didn’t want to go.

“But he didn’t say that to me at the time. I don’t think their leaving had anything to do with the trip to Africa. It was something between them and Paul, and Paul said, ‘So what? It’s booked, we’re going anyway!’ and I said, ‘Okay, fine!’ That doesn’t throw me, that kind of thing. No big deal.”

In what ways did suddenly being a three-piece shape the sound of Band on the Run?

“It didn’t really change, except that before, we would have done the backing tracks as a band. Now it was me on acoustic guitar or keyboards and Paul on drums. We would put the track down that way where he could get the drum part first. That’s how it worked on that album, and I think that’s how we got the specific feel for Band on the Run.

“Me and him had this kind of feel together musically. We slotted in well together. We could read each other, and that came from growing up on the same musical influences. Paul’s got a good sense of rhythm, and he doesn’t overplay, which I like.”

His drumming style is very idiosyncratic and recognizable.

“I think he got a lot of his style playing with Ringo, because Ringo’s a very basic drummer. He doesn’t overplay. He doesn’t try to show off and put in too many fills. So Paul just had that same approach to drumming. It’s all about having a good feel and working with the vocal. I remember on No Words, Paul forgot one of his drum entrances and came in a measure too late. But we left it in and kind of built the arrangement around that.”

Who played the famous opening lick on Band on the Run?

“Paul. It was his part. Some people think it’s doubled with me and him, but when I listen to it, it doesn’t sound that way. Usually we would double riffs. Band on the Run didn’t have a lot of guitar solos, except Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-Five, which I played the solo on. I very rarely did solos in Wings.”

It’s hard to keep Paul out of a song once he gets going. He’ll always come up with something that works

You mentioned No Words, which is one of my favorites from the album. What do you recall about writing it?

“Paul was always trying to get me to write more. I didn’t, because he was very prolific, so I kind of left it up to him. On Band on the Run, he said, 'Have you got anything?'And I said, 'I’ve got these two different ideas,' thinking it might be two separate songs. Paul said, 'Let’s join them together.' Then he added the last part, the 'your burning love' section.

“You can do that with Paul. It’s hard to keep him out of a song once he gets going. [Laughs] He’ll always come up with something that works.”

What was the studio like in Lagos?

“They didn’t have anything. It was all hand-me-down equipment. Half of it wasn’t even rigged up. There was a door in the back that opened up into a record-pressing plant, with, like, 60 people working away. As for the equipment, obviously we’d brought our own guitars and amps. Again, like on Red Rose Speedway, I was using the Telecaster and the Gibson Jumbo.”

You get the sound from your experience. That’s what you always have, so you don’t really need the new plugins and so on

It was a time before plugins and loads of effects, so tone was much more reliant on the instrument, the amp and how it was mic’d. Do you feel there’s a difference in those vintage sounds compared to what’s available now with plugins?

“It’s all basically down to how you play it. Being a rhythm guitarist mostly, I was inspired by folk music, Spanish styles and rock ’n’ roll. I’m an accompanist, so I’ve learned to play as an accompanist. Whether it’s on Paul’s songs or my own, I get where to come in and where to go out. But as far as sounds go, we experimented with all kinds of things back then, because we had to. Natural echoes, mic placement. It was all real sounds.

“I’m still a great believer that it’s down to the way you play. The sounds come from the technique and your dynamics of how you play. You get the sound from your experience. That’s what you always have, so you don’t really need the new plugins and so on.

“I think what happens is that a lot of the stuff that came after the ’60s and ’70s is people trying to emulate that original sound, but with more modern techniques. You have to have the experience to get that sound. You can’t get it through a machine.”

What do you remember about the photoshoot for the album cover?

“Clive Arrowsmith, the photographer, ran out of film on the shoot, and that’s why it ended up with that sepia color. He’d put in a different kind of film and it was a fluke that he got that certain lighting. Sometimes life’s like that, where you come up with something special by accident. It was a fun day. Very up and positive.

“For me, the big surprise was finding out that [actor] Christopher Lee was a huge music fan and knew about records and stuff. The only direction was, ‘Okay, make believe you’ve been caught in the spotlights by the prison guards.’ Everybody looked one way, and funnily enough, I looked the other way. [Laughs]”

How do you feel about the legacy of Wings?

“I’m not trying to downplay it, but I’m actually surprised we’re that well-remembered. I’m just a normal musician who doesn’t really think about the fame side of it. That always surprises me, the fame side of it. For example, a lot of my solo stuff, I never really had a big hit, but then people will come up to me and say, ‘I’ve got all of your solo stuff. I know every song you’ve ever written.’

“It’s a compliment and it does give you a good feeling. You’ve gotten across to a lot more people than you thought you did. And it’s the same with Wings. We don’t think of it in terms of how famous we were or how many people we influenced until we meet the fans. But it’s all about music for me. It’s all about moving forward. We’re never really satisfied.

“Even when a lot of people say, ‘Oh, that’s the greatest album, or I love this or that,’ we don’t. We say, ‘We loved doing it, but in retrospect, I think I could’ve done that better.’ Or ‘I wish I hadn’t done that.’ You never stop creating, and therefore you’re never 100 percent satisfied. You can’t be. But when the finished product goes out and a lot of people are happy with it, that’s good enough encouragement for me.”

What are your latest projects?

“I’m working on new material for an album. Before the pandemic, I started doing solo acoustic shows and that started to go down really well and I was enjoying it. Now, starting in February [2023], I’m going to be doing the City Winery venues. New York, Nashville, all of them, and filling in shows in between.

“I can’t be strictly a studio guy. That’s how I came up, playing live. I think that’s the way the best records are made. You take that energy you get from performance and bring it into the studio. Then you come out with something good. It’s a hard thing to do in this business, but that’s what you need to do. It’s all about balance.”

Bill DeMain is a correspondent for BBC Glasgow, a regular contributor to MOJO, Classic Rock and Mental Floss, and the author of six books, including the best-selling 'Sgt. Pepper at 50.' He is also an acclaimed musician and songwriter who's written for artists including Marshall Crenshaw, Teddy Thompson and Kim Richey. His songs have appeared in TV shows such as 'Private Practice' and 'Sons of Anarchy.' In 2013, he started Walkin' Nashville, a music history tour that's been the #1-rated activity on Trip Advisor. An avid bird-watcher, he also makes bird cards and prints.