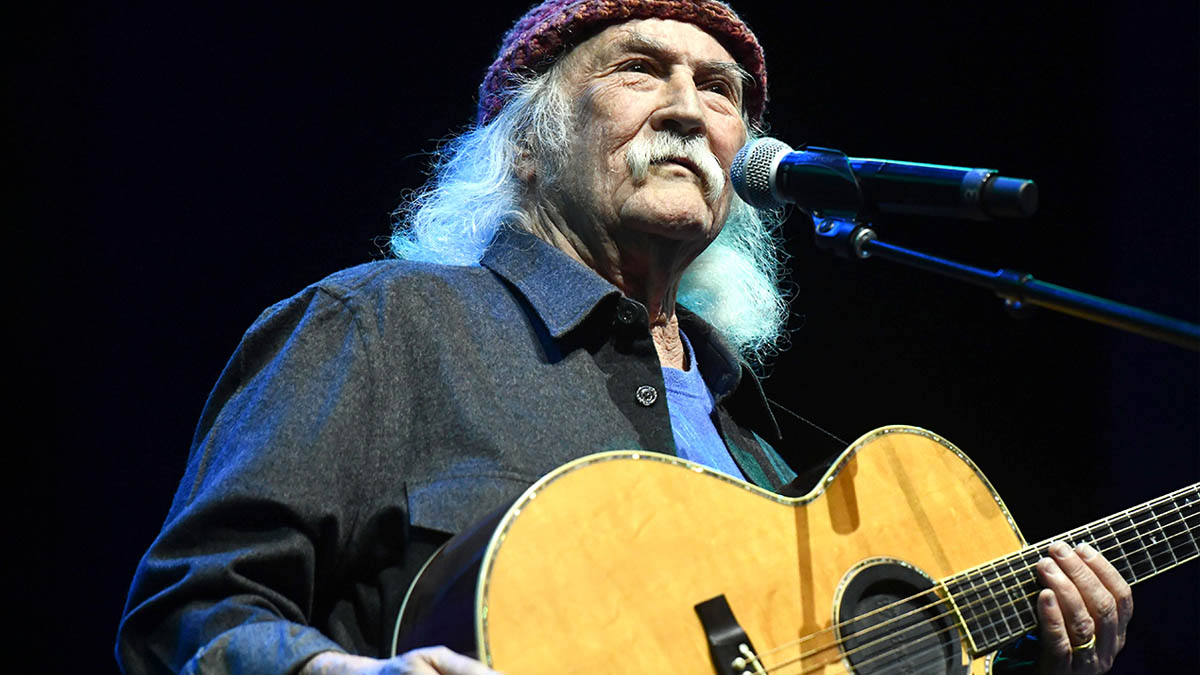

David Crosby: “I’m usually trying to tell a story. Musically, I think it has to do with the fact that I like more complex chord structures and progressions”

In one of his final guitar interviews, the free-thinking founder of The Byrds and CSNY reflected on his storied career and discussed the making of his final, Joni Mitchell-inspired album, For Free

David Crosby, who passed away on January 18 at the age of 81, was one of the leaders of a musical revolution inspired both by British invasion bands of the '60s and the music of the American folk and blues minstrels.

Alongside fellow singer-songwriters Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell and James Taylor, they melded their influences into a new kind of electro-acoustic folk-rock, using open tunings and introspective lyrics, often layered up with glorious vocal harmonies.

Crosby was at the heart of The Byrds and several iterations of the Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young brand and continued to work with various members for many years.

This included recording, gigging and doing sessions with Nash, as on David Gilmour’s solo album On an Island, plus legendary Royal Albert Hall appearance Remember That Night (captured on DVD). Crosby and Nash also sang on John Mayer’s Born and Raised, and on tracks by Elton John, James Taylor and many others.

However, always interested in new singers and writers (who were even more interested in him), he never stopped making musically relevant and highly listenable music, both on solo albums and as collaborations with a number of contemporary artists, including Snarky Puppy’s Michael League.

Crosby’s final studio album was aided by his musician-producer son James Raymond, and was part homage to Joni Mitchell, with the title-track cover of her ballad, For Free.

The album also included collaborations with Texan singer-songwriter Sarah Jarosz, plus vocal additions from Doobie Brother Michael McDonald, and a long-awaited co-write with Steely Dan legend, Donald Fagen.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In this conversation, which was conducted in late-2021 and marked one of his final guitar interviews, David joined Guitarist by phone from his California homestead to discuss his approach to songwriting, his love of Martin acoustic guitars and the golden era of the Laurel Canyon scene.

You’ve made the new album For Free with your son James Raymond, who produced it, co-wrote some tracks and played piano on it.

“Yes. A wonderful cat, too, man. He’s a really, really decent guy and he loves making music, and so we have a blast doing it. We have a record that we haven’t even put out yet, and we are already recording the next one. It’s a joy to work with him. He has just turned into the best record producer and the best writing partner that you could hope for.”

In your work with bands, you could always recognise the Crosby songs. Is it a certain attitude that sets you apart?

“I think it has to do with the fact that I’m usually trying to tell a story of some sort, and I think it has to do musically with the fact that I like more complex chord structures and progressions. I did listen to a lot of jazz, and so I like dense, unusual chords. But if you try to shape it to what the pop taste is at the moment, you listen to everything that’s succeeding and then you try to be just like that – it doesn’t work for me.”

Did you play guitar on new album, For Free? And if so, what tunings did you use?

“Yes, I did. I used the tuning [EBDGAD] on the track I played the most on, which is I Think; I have a good guitar part on that. There are guitar parts on some of the others, but it hasn’t been a major thing on this one.”

In previous interviews, you’ve mentioned the difficulty you might have playing guitar because of your hands. How is that affecting your playing?

“I’ve lost a percentage, maybe 10 per cent, maybe 15 per cent. But I can still play, just not quite as well as I used to. It’s heading in the wrong direction. There isn’t anything anybody can do about it. It’s tough, but whining isn’t going to help anybody. All my guitars are set up as low as they will go. I can play, but I know in the long run I’m going to lose it.”

From the very beginning, vocal harmonies have been integral to everything…

“Well yes, they are for me. I love them, and if there is a chance to do those dense chords that I like, I always will. Most commonly, although we did it in every possible variation, Stephen would sing the melody, I would sing the middle, which is the hard one, and Nash would sing the top. All the harmonies in The Byrds are me. The Byrds is basically two-part, although sometimes Gene [Clark] was in there, too.”

You emerged at a time and in a place where the music was spectacular…

“There was a plethora of really talented people really trying hard to make good music, and that was a wonderful thing.”

CSNY, Joni Mitchell and James Taylor all released landmark albums in 1970, the year The Beatles broke up. The pendulum swung from British to American. You guys had the talent and were making all the moves.

“Thanks, man. I think Joni was a thing on her own. She is probably the best singer-songwriter that ever lived. But I think, yes, it did shift to the United States right then, but I’m sure it shifted back when Pink Floyd happened.”

I’ve been saying for a while that probably the two best singers in the United States are Stevie Wonder and Michael McDonald

It must have made everybody raise their game because you had these friends putting out brilliant stuff?

“If I think about it, I knew that there were all these other people who were really good. People I was competing with were James Taylor and Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan and the singer-songwriters. Nobody could compete with The Beatles, but we did compete with the singer-songwriters and we generated a whole lot of really wonderful songs.”

There are some great collaborators on the new album, the instantly recognisable Michael McDonald helps out in the opener River Rise, for instance.

“I’ve been saying for a while that probably the two best singers in the United States are Stevie Wonder and Michael McDonald. Michael is the best singer I know. [Everybody] heard him on Steely Dan records and went, ‘Holy shit!’ And those hits with The Doobies, ‘Holy shit!’”

There is some great guitar on the record from Shawn Tubbs, and from session legend Dean Parks.

“Shawn was an LA guy, but he moved to Texas. I sent a couple of things down to him and got him to play them. Dean is just a freaking genius. I just did another thing with him. It was so much fun I couldn’t believe it.”

On this album, when you recorded the tracks did you layer everything up or did you learn the songs as a band and put them down in the studio?

“We had to do it piecemeal because of the pandemic. So these were built piece by piece, but I always have done it the other way.”

In a normal situation do you like to have control over what people play?

“No, no, I get really good musicians and then I listen to what they do, unless there is something more that I want I tell them. But the best thing is, see what they come up with because they are probably going to come up with something you didn’t think of, which may be absolutely fucking wonderful. So don’t close the door!”

Rodriguez For A Night has lyrics by Donald Fagen. That song really nails those Steely changes, doesn’t it?

“Yes, we went for it, no question. We love Donald. We loved Steely Dan. Aja and Gaucho are both in my Top 10 for life, up there with Blue [Joni Mitchell], Heavy Weather [Weather Report], and Kind Of Blue [Miles Davis]. There’s a handful of records, and two of theirs are in there.”

The title track, For Free, is such a simple song, but you can’t slavishly copy it. So how did you and Sarah Jarosz approach it?

“I had listened to her singing with Sara Watkins and Aoife O’Donovan in I’m With Her, their band together. They are fantastic. Then I listened to Sarah Jarosz’s record, Build Me Up From Bones, a fantastic record. Then she put out World On The Ground and it was even better. I couldn’t stand it.

We sent For Free off to Sarah Jarosz and she sent it back with that harmony on it, which is like a lesson in how to do harmony. Just f**king perfect

“I got hold of her and I said, ‘Listen, this is a stunning record. I really love your stuff and I’d like to sing something with you. I don’t know what. I don’t know where. I don’t know where we’d put it. I just want to do it because it’s fun.’

“She said, ‘I’d absolutely love to.’ I said, ‘Okay, let’s figure out a song and we’ll sing it. We are not trying to accomplish anything. We just want to have some fun. How about ‘For Free?’ She said, ‘Oh, I love that song.’ Then I went to James, and James did a piano track for it that is so evocative and so beautiful that it made me sing it better than I’ve ever sung it. I transcended myself.

“We sent it off to her and she sent it back with that harmony on it, which is like a lesson in how to do harmony. Just fucking perfect. I called her up and said, ‘Listen. Can I put that on my record? It’s just so good.’ She said, ‘Of course you can. I think it’s fantastic.’”

James also plays a lovely piano part on I Won’t Stay For Long. He wrote the song, too, even though it could be something autobiographical from you...

“He wrote it and it’s the best thing on the record. He says that he wrote it off [the Greek legend of] Orpheus and Eurydice. Hmm-hmm.”

Onto guitar, you were all playing Martin D-45s around the Woodstock era…

“Yes, And we loved them. I have three 1969 D-45s. But I have a bunch of really great guitars, man. I didn’t buy famous people’s guitars; that’s what Nash did. I think he probably made more money on it than I did. But I bought guitars that played unbelievably well. I have probably the five best acoustic 12-strings in the world.

“I have a [Martin 12-string] that was converted from a D-18 that I bought in a store in Chicago. It’s the best guitar I’ve got. It’s louder and more resonant with more overtones than anything else I’ve ever played.

“I’d always been drawn towards Martins until I ran into a guy right outside Seattle named Roy McAlister. I have five of his guitars. That should be everything you need to know right there.”

Streaming doesn’t pay us. It’s like you did your job for a month and they gave you a nickel. You’d be pissed

You recently sold your publishing to help fund your life. That must have been a big burden lifted.

“We had two ways of making money: touring and records. Streaming doesn’t pay us. It’s like you did your job for a month and they gave you a nickel. You’d be pissed. That’s why we are pissed – because they are making billions and not paying the people who are creating the music. So I’m trying to be grateful that I can still play live and pay the rent and take care of my family. But along comes Covid and I can’t play live. That was it. Now I’m broke. I don’t want to lose my home, man.

“We’ve got an old adobe house here in the middle of a cow pasture. It’s just fucking wonderful. A beautiful, beautiful place in the middle of a bunch of trees. It’s just lovely; it’s not fancy and it’s not rich and it’s not big, but it’s really right. We want to live here all our lives, so I sold my publishing.”

People still want to hear new music from you – and not every musician from the era you came up in can say that.

“Nope. I guess I’d better keep trying…”

In the late '70s and early '80s Neville worked for Selmer/Norlin as one of Gibson's UK guitar repairers, before joining CBS/Fender in the same role. He then moved to the fledgling Guitarist magazine as staff writer, rising to editor in 1986. He remained editor for 14 years before launching and editing Guitar Techniques magazine. Although now semi-retired he still works for both magazines. Neville has been a member of Marty Wilde's 'Wildcats' since 1983, and recorded his own album, The Blues Headlines, in 2019.

“It combines unique aesthetics with modern playability and impressive tone, creating a Firebird unlike any I’ve had the pleasure of playing before”: Gibson Firebird Platypus review

“I met Joe when he was 12. He picked up a vintage guitar in one store and they told him to leave. But someone said, ‘This guy called Norm will let you play his stuff’”: The unlikely rise of Norman’s Rare Guitars and the birth of the vintage guitar market