“I introduced Sting to Miles Davis, and that blew Sting’s mind!” Darryl Jones on providing the punch for Sting, Madonna, and the Rolling Stones

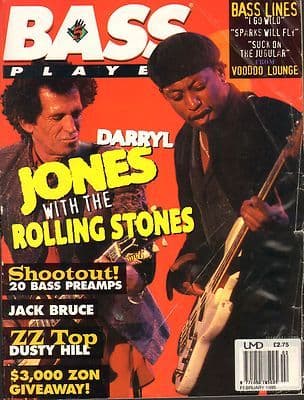

After stints with Miles Davis, Madonna, and Sting, Darryl Jones found a home on The Rolling Stones’ Voodoo Lounge

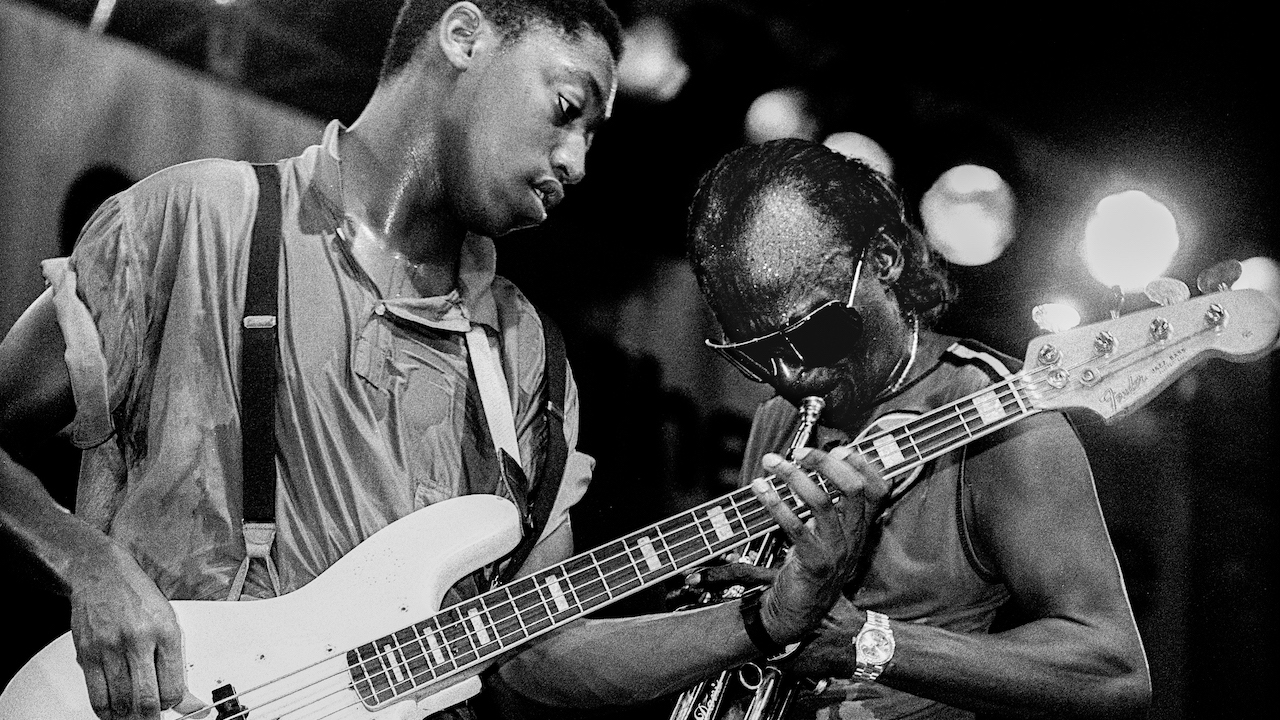

It’s been three decades since Darryl Jones made his debut performance with the Rolling Stones on 1994’s Voodoo Lounge, which was followed up with a much-publicised world tour. But the job of playing bass guitar with the Stones isn’t something you just fall into. His first major gig was with jazz giant Miles Davis.

Jones recorded two albums with Davis, You’re Under Arrest and Decoy, and went on to perform with Sting, Madonna, Peter Gabriel… the list goes on, but what was it about this jazz master’s approach that let him fit into rock & roll so well?

“When the Stones were looking at bass players, they looked at my name on the list and someone said, ‘Darryl Jones… who’s he played with?’ ‘Miles Davis,’ came the answer. ‘Let’s get him in…’ It doesn’t matter who it is, that’s always been the reaction. I introduced Sting to Miles, during the recording of You’re Under Arrest, and that blew Sting’s mind! Miles had everyone’s respect.”

Jones was as surprised as anyone in the bass community when he ended up playing on 15 of the 17 Voodoo Lounge tracks with the Stones (Keith Richards provided the bottom on Brand New Car, and Max Baca played a banjo sexton on Sweethearts Together). “Recording with the Stones is like getting on and off a train,” he told BP. “And whoever’s on the train when it stops is who’s on.”

The following interview is from the February 1995 issue of Bass Player.

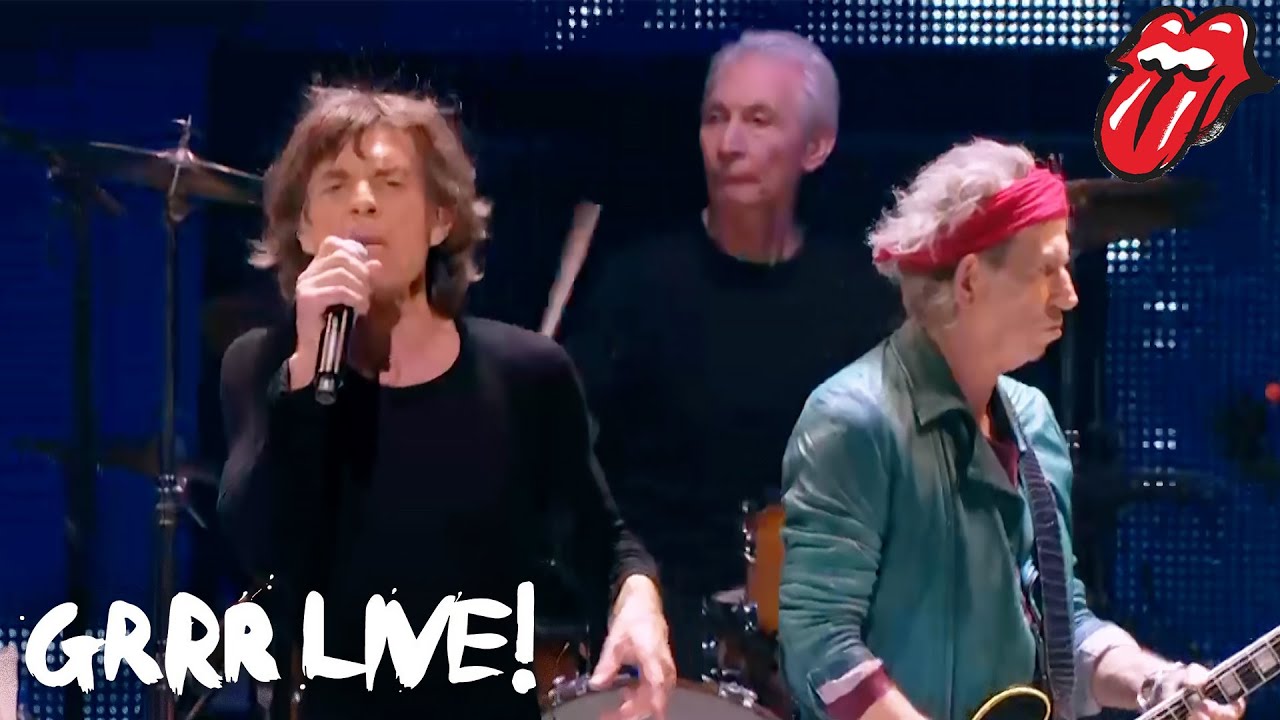

How did you land the gig with the Rolling Stones?

“I met Mick Jagger in 1985 while I was working on the film Bring On The Night with Sting, and I met Keith in 1987 through Charley Drayton and Steve Jordan, who were working on his Talk Is Cheap record. When I found out Bill Wyman was leaving, I called Mick Jagger’s management and left a message saying I was interested in auditioning. I also tried sending messages to the Stones through friends. I don’t know which method worked, but I got on the list.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Why did the gig appeal to you?

“When I saw Keith with the X-pensive Winos, I began to think it might be interesting to play some rock & roll. My first thought was if Keith’s gig became available, I’d be into trying it out. It didn’t, but when Wyman left, I thought, ‘Well, why not the Rolling Stones?’”

What was the audition process?

“I was asked to come to New York in June 1993. We played through a bunch of hits; Brown Sugar, Miss You, Tumbling Dice, Start Me Up. Everything felt good and I thought, ‘No matter what happens, I’ve had a lot of fun – and maybe I’ll hear from them.’ They called again in October: this time they wanted to play through material they’d written for Voodoo Lounge. After that, they asked me to come to work on the record in Dublin. There were rumours of a tour, but nothing official was said.”

Did you feel a bit intimidated about working with them?

“Not at all. There’s a mutual respect, and this is a situation that’s about everybody having fun making music. The Stones opened their arms and tried to make a place for me, so it’s been really cool.”

How did you research for the audition?

“Basically, I got a few of their ‘best of’ records and played along. Instead of learning Bill Wyman’s parts verbatim and then trying to sound like him, I learned the form of the songs and the general shape of the basslines, and then I added my own interpretations. I felt it was important to play in my own style so they would be hiring me for me. On certain songs, however, I play the lines note-for-note because they’re essential parts – like in Start Me Up and Satisfaction.”

There are a few Wyman-esque lines on Voodoo Lounge – like the opening riff of I Go Wild and the octave climbs in the bridge of Suck on the Jugular.

“I can’t think of any sections where I tried to cop his exact style. I actually borrowed the octaves on Jugular from the Jaco Pastorius line on River People. It’s my little tribute to Jaco.”

How did you come up with your bass parts for the rest of the album?

“In some cases, I’d just pick up the bass and play whatever I felt was needed for the song, and that worked well. On other songs, Mick might ask me to drive a section harder or move from straight-eighth notes to a figure – or he’d sing a line and I’d work on it. He would always say that if I wasn’t comfortable with something he suggested, I didn’t have to play it – so I was given a lot of freedom. Mostly, I just used my intuition.”

The steady eighth-note pattern seems to be the staple of rock bass playing.

“That’s often the case, and I’ve certainly gained a better understanding of the intricacies involved. There are a thousand ways to play eighth-notes with respect to left-hand articulation, right-hand attack, note choices, note duration, use of space, phrasing, and overall feel. Then again, sometimes I’ll start playing an eighth-note line with two right hand fingers, only to find out that using anything more than one finger is overkill.”

Did you feel obliged to use a vintage bass?

“That was my first inclination, and I did use a Fender for the audition to make that point, but at the same time, Roger Sadowsky’s basses are built so much in the Fender-style, and he uses the active electronics to enhance, rather than change, the sounds. That became especially clear when we recorded. I used Fenders on certain songs, but there was something about the warm, fat, round tone of my Sadowsky. I’d say I played it on 45% of the album. In fact, Don Was – a fellow bassist – called Roger and said ‘Send me a bass just like Darryl’s.”

What’s your assessment of Bill Wyman’s playing?

“Even though he isn’t usually in the forefront when people talk about the Stones sound, Bill Wyman is, in my estimation, an underrated bassist. I’ve been listening to his lines, the different approaches he took to songs. He obviously knew a lot about this music after playing it for so long.”

Is that a fretless acoustic bass guitar on Mean Disposition?

“Yes – Ronnie’s Zemaitis fretless. I muted the strings with my left-hand and plucked them with my thumb to get a Willie Dixon-type sound. It has an old R&B feel, with Charlie swinging the ride cymbal, but rockin’ the rest of the kit.”

Did you and Sting ever have any bass intensive conversations?

“Not really, but he wrote some great basslines, and my ear was open to that. What impressed me most about Sting, besides his obvious gifts as a composer and lyricist, was that he combines idioms so well – and that allows him to create his own music and his own market.”

What was your musical approach with Madonna?

“Because of the nature of the music, a lot of the basslines needed to be played pretty much verbatim. The most interesting aspect of that tour was watching her use all of the available resources to make her vision a reality.”

It seems that playing with Miles exposed you to much of what you would later encounter with pop and rock acts?

“That’s true. Miles played the blues, and he played pop songs, like Cyndi Lauper’s Time After Time. He performed infront of huge audiences, and there was a vast amount of media attention. When I joined Sting’s band, people would ask about the difference between playing behind a trumpet and playing behind a voice, and I’d say, ‘Man, Miles is a voice!’”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.

“One of the guys said, ‘Joni, there’s this weird bass player in Florida, you’d probably like him’”: How Joni Mitchell formed an unlikely partnership with Jaco Pastorius

“I said, ‘If I could have it my way it would sound like this,’ and I pulled the bass guitar out of the mix”: Why Prince removed the bassline from When Doves Cry

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)