Cry Club: “We want to be making stuff that connects with other people”

Equally charismatic and chaotic, the debut album from Cry Club is a revolutionary pop-rock romp you'll need to hear to believe

There aren’t enough pages in this whole magazine to cover everything there is to know about Cry Club. In two absolutely stacked years of back‑to‑back bangers, the kaleidoscopic Melbourne‑via‑Wollongong pop duo have proved three things to be true:

1. They can make virtually any vibe gel effortlessly with their fantastical fusion of synth and shred – from molten, math-inflicted punk chaos (“Robert Smith”) to deep, smoke-soaked club house (“DFTM”), to shimmery, ‘90s-channeling acoustic balladry (“Lighters”) and everything in-between.

2. They don’t need a room full of songwriters or a billion-dollar budget to make pop music capable of rivalling the biggest names out there. Their forthcoming debut full-length was recorded on one guitar – a slightly dodgy homemade Jazzmaster that rifflord Jonathon Tooke built at 17, no less – on a budget that would make you think the band sold their soul to Satan for soundscapes as tight, rich and clean as they mustered.

3. They are truly unstoppable. Heather Riley [vocals] and Tooke were just one date shy of wrapping up a sold-out national tour in support of “Robert Smith” when the Coronavirus pandemic hit, and despite being unable to get back out on the road, hype surrounding them has only skyrocketed in the last few months – thanks in no short part to the announcement of that aforementioned debut, God I’m Such A Mess.

Before the album launches next month – after which we’re giving it a year before Cry Club become the biggest name in Australian music – we caught up with Tooke to vibe on how he and Riley whipped up their masterpiece.

How did you find that this album shapeshifted as you worked it?

It’s an interesting one, because it was made over such a long period of time. Our producer, Gab [Strum]… He’s a busy boy! There were points where we were like, “Alright, you’re going to America for two months, can we just get a bunch of sessions in before you go?” And then he’d come back from America and go on his own tour for the Japanese Wallpaper project, and then he’d be DJ-ing for Allday for a month or two. And in the meantime, not only was he doing our record, but he’d be in the studio five or six days a week with multiple different people and projects. So it was just a case of finding the times that worked for all of us.

At the start, it was like, “Okay, we need to focus on the singles,” because we didn’t have the time to really dive into a full record. And then when it came time to go, “Alright, let’s get into the album tracks,” we hit an impasse and Gab was like, “You know you’re allowed to have intros on the deep cuts, right?” We had this one song, “Wish” – it was an audience-favourite track from the early days but it was too slow to play in half-hour sets, whereas it works really well on a 45-minute long album. Because y’know, if you’re investing yourself into that much time for one band’s music, there’s only so much 150BPM pop-rock you can handle in one bite.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

One thing that really stands out about this project is that when you combine both of your personalities as artists, you get this very powerful style and character that is entirely unique to Cry Club. Between your background in audio engineering and history playing in heavier and more technical bands, and Heather’s history with musical theatre and acting, do you find that your respective cultural upbringings are integral in cracking the code behind Cry Club?

For sure. I’ve been playing in bands for, like, ten years now, and I’ve experienced all the positives and negatives that come with that. I was a session player for a while, I toured with Bec Sandridge, I played in a twelve-piece gospel band and a mathcore band, going and playing all these weird house shows and that sort of stuff… And I think coming out of that, if I was to collect all of those experiences and describe how they intersect with Cry Club, it would be that I just want to be more direct with this project. I want it to be audience-facing.

I’ve seen a lot of projects where it’s like, “This is just for our own satisfaction.” The biggest Cry Club fans in the world are Heather and I, because we endlessly listen to our own music, but we want to be making stuff that connects with other people as well, and making sure that the bridge between us and them is less opaque. We can play some really wild stuff – the end of “Dissolve”, for example, is this crazy huge key signature change, and we have that riff in “Robert Smith” where it’s in 9/4 – but we try to frame those things in a really accessible way. I have this whole philosophy that if you’re doing something complex, you need to frame it simply, and if you’re doing something simple, you need to frame it in a complex

way – just so that it’s constantly engaging.

At the root level, how does a Cry Club song come to life?

For a lot of what the first record is, because every song was approached with the idea that we want to play it live, our formula was that it had to start with a drum part that could be performed by a real drummer, a bass guitar part and one guitar part, and then a vocal. And the song has to exist completely within that structure –

if it’s not working with those super minimal elements, then those elements need to change. And then when it comes to the production, that’s where we can start layering all the other stuff on.

A lot of the songs on the record started with me working on an instrumental with those basic elements, and then Heather and I working on a vocal and writing the lyrics together, and then stepping back and going, “Alright, where can we push this?”

What can you tell us about your go-to guitar?

Heather makes fun of me because of how many times I tell this story, but it’s actually a guitar that I put together as a teenager. Because at the time I couldn’t afford a real Fender Jazzmaster – the only Jazzmasters you could buy in shops were, like, $2,500, and I was 17 so I obviously didn’t have that money! I was on a website called offsetguitars.com – that was the forum I spent all my time on as a teenager, which says everything you need to know about me as a person – and I was asking everyone, like, “I want to put together a Jazzmaster! Here’s my plan! What does everyone think?”

So the neck and the body come from a company named MJT, and the pickups are Curtis Novak pickups that were wired in by a company called Rothstein Guitars. It has a standard Jazzmaster neck, and then the bridge is a stacked P-90, so it’s a P-180, and I made them give me a little coil tap so that when it’s up, it’s just a standard P-90. It’s wired so that the neck pickup is standard, but this back one is so hot that it redlines anything it gets near. Anytime I need some super crazy, like, there-is-no-transience-to-my-guitar-at-all kind of stuff, it’s like, “Alright, back pickup time!” I have a bunch of other guitars at home, but this is the only one I have in the studio at the moment, because I’m only working on Cry Club stuff right now.

So why that guitar for Cry Club?

I wish I could give you a really technical answer like, “Ah, I love it’s midrange, and the sustain is great” – but the sustain on it is actually shit, and I can’t even bend on it because it’s a ‘60s-style neck and it’s got this giant curve. But it has an extended scale length, and it works really well in alternate tunings – all Cry Club songs are in E standard, but the G is an F#; that’s just to make me dumb enough to do weird stuff. And a lot of my guitars on this record are incredibly dry. Because the part just needs to be good – I can layer it in effects after the fact, but in the moment, I just need to make sure the part is right.

I’m doing a lot of effects in Pro Tools that I’m trying to match live, but honestly, a lot of it is just caveman shit. I am by no means a tone wizard – I pull up the same NI Guitar Rig preset every time I start playing this guitar on a song. I want to make sure my parts work well without effects, so that when I do apply them, it’s like I’m icing the cake, not just trying to cover up a mistake.

Ellie Robinson is an Australian writer, editor and dog enthusiast with a keen ear for pop-rock and a keen tongue for actual Pop Rocks. Her bylines include music rag staples like NME, BLUNT, Mixdown and, of course, Australian Guitar (where she also serves as Editor-at-Large), but also less expected fare like TV Soap and Snowboarding Australia. Her go-to guitar is a Fender Player Tele, which, controversially, she only picked up after she'd joined the team at Australian Guitar. Before then, Ellie was a keyboardist – thankfully, the AG crew helped her see the light…

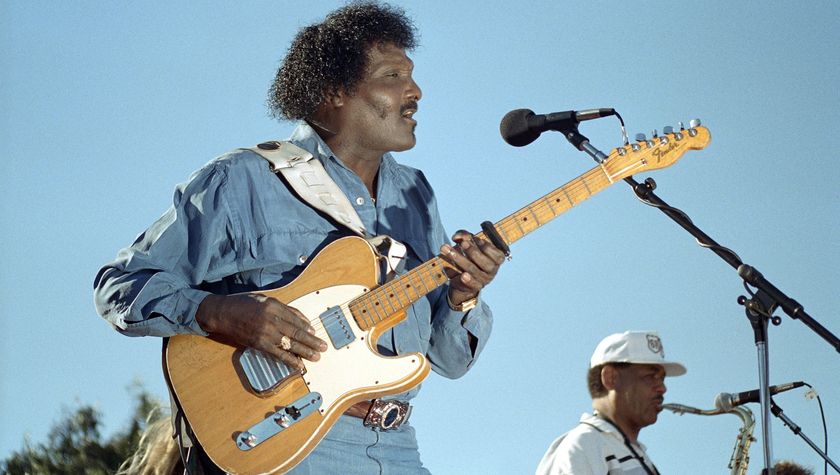

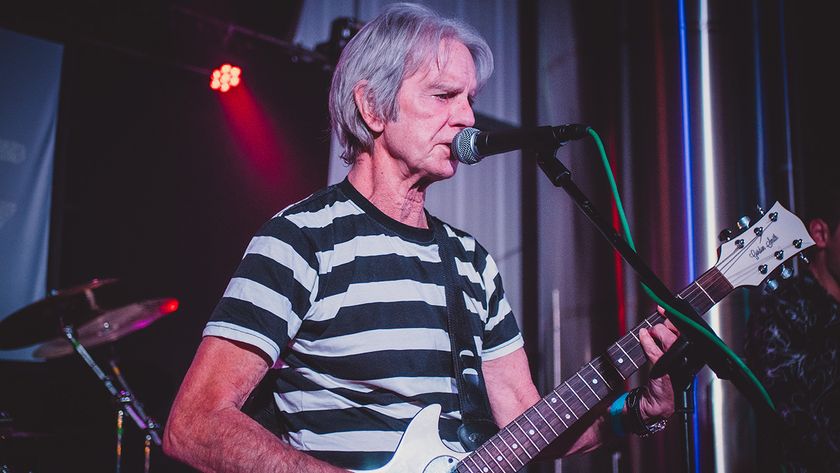

“I get asked, ‘What’s it like being a one-hit wonder?’ I say, ‘It’s better than being a no-hit wonder!’” The Vapors’ hit Turning Japanese was born at 4AM, but came to life when two guitarists were stuck into the same booth

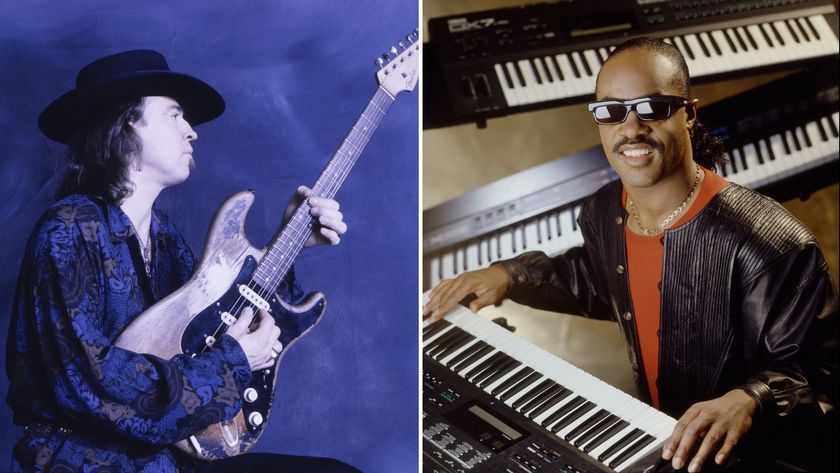

“Let's play... you start it off now, Stevie”: That time Stevie Wonder jammed with Stevie Ray Vaughan... and played SRV's number one Strat

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)