How Cliff Burton shaped Metallica's expansive thrash assault – and changed the sound of metal bass guitar forever

We celebrate Burton's career, and dig into his tones and talents with the help of Metallica’s incumbent bassist, Robert Trujillo

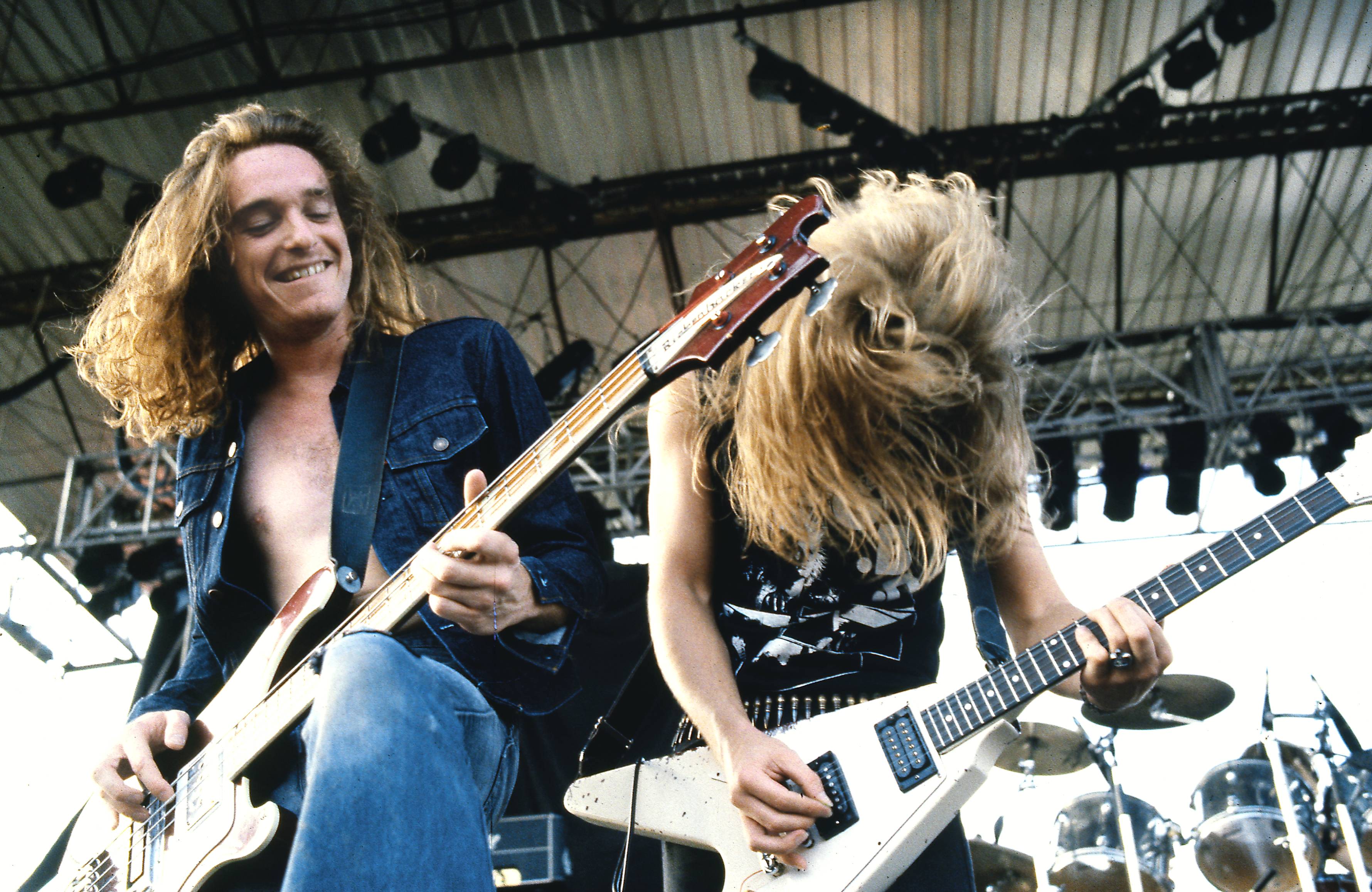

“The major rager on the four-string motherfucker”, as the late Cliff Burton was approvingly described during his first gig with Metallica on March 5, 1983, is a revealing phrase. It’s a very California-in-the-’80s thing to call a musician, one part Bill & Ted and one part Spinal Tap, but at the same time it’s completely perfect.

The “major rager” tag was bestowed on Cliff by Metallica’s then-guitarist Dave Mustaine, something of a rager himself, and it has gone on to represent an era of heavy metal – and specifically, the beginnings of garage-level thrash metal – that still entrances a tribe of metalheads, even those too young to witness it in person.

Nowadays, Metallica are huge, with a brand as powerful as that of Led Zeppelin or the Rolling Stones, and they’re in their fourth decade of playing arenas. Back then, Cliff plus the other three members James Hetfield (vocals, guitar) and Lars Ulrich (drums), and either Mustaine or his successor Kirk Hammett, were young, broke, and feeling their way into a new sound that was influenced equally by classic metal and hardcore punk.

Thrash metal was fast, obnoxious, and unsophisticated at first, but soon evolved into a more polished sound. Many of you will already know all the historical details, so I won’t go too deeply into the chronology here, but with their first three albums Metallica established an influential template that, purists argue, even the band themselves have not surpassed.

Cliff was a huge part of this, even though he was only a member of the band from 1983 to his death in September ’86. Heavy metal bass guitar was not known for being particularly inventive before he came to prominence, the blues and prog explorations of Black Sabbath’s Geezer Butler and Steve Harris of Iron Maiden aside – but right from the off, Cliff was unstoppable, even playing a bass solo track called Anesthesia (Pulling Teeth) on Metallica’s debut album, Kill ’Em All (1983).

“Cliff strikes me as a player who would have said, ‘This is how we’re doing it’,” says Robert Trujillo, Metallica’s bass player since 2003. “He had a vision, and he would go for that vision. Rather than a producer trying to control him, I could see Cliff having an idea for what statement he wanted to make with the instrument. More power to him – Jaco Pastorius was the same way.”

Trujillo, the producer of the acclaimed 2014 biopic Jaco, invokes the comparison seriously. “Somehow, Cliff would have the freedom to express the instrument and give it a personality that it did not have before in metal. He took that attitude and edge that the fusion players had, and he brought it in – and especially in thrash metal, that was pretty impressive.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Cliff’s uncompromising attitude was just one aspect of his character as a bass player: he brought unique influences, powerful technique, and his own tone. Those were assets in his favor, and therefore the band, with whom he recorded parts that metal bassists still learn as a part of their basic training.

He had an extreme connection to classical music, and you could hear that in him as a composer, but at the same time he loved punk rock

Rob Trujillo

Anesthesia, with its famous classical motifs derived from J.S. Bach and a hugely overdriven tone, was just the first of these. Burton fans will also point to his intro line in For Whom The Bell Tolls and the fills in The Call Of Ktulu from the 1984 album Ride The Lightning, as well as the intros and solos in Orion and Damage, Inc. from Metallica’s masterpiece Master of Puppets (’86), as his career-best parts.

“Cliff’s style was very aggressive,” explains Trujillo. “When I joined Metallica, I became more familiar with him as a composer, and where he was coming from creatively. That’s when I realized how special he was, because of his influences. He had an extreme connection to classical music, and you could hear that in him as a composer, but at the same time he loved punk rock. This guy came from the same place that Stanley Clarke was coming from. He was one of those kinds of players.”

A gearhead from the time he started playing bass at the age of 13, Cliff’s most famous instrument is his 1979 Burgundyglo Rickenbacker 4001, uniquely modded with three replacement pickups: a Gibson EB, a Seymour Duncan stacked Jazz, and a Duncan Stratocaster pickup under the bridge for extra top end.

It’s this bass that you can hear on Kill ’Em All and Ride The Lightning, but by the time of Master Of Puppets, he had switched to an Aria Pro II.

This bass has become so associated with him that a signature instrument was released in 2013, followed by a Burton wah pedal from Morley two years later.

Finding Cliff’s tones, let alone playing his parts, presented quite a challenge for Jason Newsted, who was Cliff’s successor, and for Trujillo, who successfully auditioned after Newsted quit in 2001.

Fortunately, expert help was at hand. “When I joined Metallica, my bass tech Zach Harmon had a pretty good idea of what direction we would want to go for that tone,” says Trujillo, “but we also had ‘Big’ Mick Hughes at front of house, who was a part of that original team. All those factors help when you’re trying to dial the tones.”

The Aria bass has a lot to do with Cliff’s sound as well. It’s a very midrange, edgy tone

He adds: “Although I don’t play Aria, the Aria bass has a lot to do with Cliff’s sound as well. It’s a very midrange, edgy tone, as you know. My son Tye [now in Suicidal Tendencies] plays an Aria, and it’s a great tone; it cuts through. So there’s a lot of factors that would go into how to get that tone, including the Morley pedal. All that stuff plays a role.”

Presumably he models Cliff’s sound, rather than attempting to replicate the old gear?

“I do. It depends on the gig, but I’ve embraced the modeling systems. There’s a lot of efficiency in that, in the way we tour and the size of how we tour. I use a Fractal, although I’m just gonna tell you and all your readers this: there’s nothing like air moving behind you from a stack of speakers and the amp of your choice, which for me would be an Ampeg SVT from the early ’70s, just pumping air and hitting my ass. There’s no better feeling.”

Then there’s Cliff’s picking technique to consider. A two-finger player from the Steve Harris school, he still managed to play the tremolo parts on mercilessly fast songs such as Disposable Heroes and Fight Fire With Fire, and in uptempo song sections like the final part of No Remorse with ease.

He could hold it down with the two fingers at a high speed and maintain the attack – and that’s really special

Rob Trujillo

Trujillo, a three-finger player, salutes his predecessor’s incredible facility. “Two-finger picking has feel: it’s definitely a really grooving sort of way to play that fast stuff, and Cliff was a master of that. He could hold it down with the two fingers at a high speed and maintain the attack – and that’s really special.

“When I first joined Metallica, I would actually start cramping up, so over the years I devised a three-finger method. Now I can cover all the tempos pretty well, and if things get too fast I throw in the third finger, but I do try to hang in there with the two-finger system as much as possible, because it just feels really good.”

As Cliff’s supportive, non-solo parts on Lightning and Puppets are mixed fairly low, Trujillo had to work hard to learn them when he joined Metallica. Remember, back in 2003 we didn’t just go to YouTube to see what notes to play...

“Half the time, if I want to figure something out, and it’s complicated or I can’t hear it, I just go to YouTube and go, ‘Oh, there it is!’ because you hear the bass on its own. Back then, though, I did a little bit of everything. I had those Cherry Lane [transcription] books, believe it or not, because I didn’t know where to go. I was thrown all these songs that I had to learn, and depending on the album or the song, sometimes the bass was mixed a little low, and I had to wing it.

“I did as much as I could on my own, and then when I got together with James, I knew that he would help me fine-tune whatever I needed. He was obviously very helpful, but I didn’t want to take all his time and go ‘How does this go?’ or ‘What did Cliff do here?’”

“For the first couple of years, I was literally just hanging on,” he chuckles. “And what ended up happening was I got tired of hanging on, so I started learning songs that Metallica wasn’t playing. The Call of Ktulu and Orion hadn’t been played; we hadn’t even done Anesthesia until the Puppets anniversary show in 2006, so I started preparing for all this stuff maybe two years before, because I didn’t want to be caught at the last minute, trying to figure those songs out. I did a lot on my own, to stay ahead of the game, because for the first three years I was chasing it.”

Newsted, a very different bassist to Burton who used a pick for immense solidity, but who was also required to play much simpler parts than his predecessor, presented less of a challenge, Trujillo says.

“You could hear Jason’s parts better for sure, and they were a bit more delegated, but still great, though. Those players are completely different, but they’re both really, really great at what they do. There’s an art to simplicity, and Jason brought that art. Obviously Cliff was very aggressive, very melodic, and a busier player, but very tasteful, so it’s not like one way’s better than the other. Everybody knows that, but it would be safe to say that his parts were easier for me to learn, for sure.”

Trujillo, still yet to find fame in the crossover punk/metal band Suicidal Tendencies when Cliff died in 1986, never met the great man.

“I never met Cliff, but I wish I would have,” he says. “I have friends that I grew up with who met Cliff, and a lot of the guys in the Suicidal camp met him. It’s weird: one of my best friends is Mike Bordin of Faith No More, and another great friend is Jim Martin [formerly of the same band], and both of those guys were best friends with Cliff.

“When I joined Ozzy Osbourne’s band and Mike was the drummer, I’d see photos of him and Cliff at Mike’s house when I’d come up to stay with him in San Francisco. I could feel this energy and vibe there, with the spirit of Cliff. I didn’t know him, but it’s always nice to feel the connection.”

For decades after Cliff’s death, his father Ray Burton represented him among Metallica’s fanbase, right up until he passed away in 2020 at the age of 92.

“Ray Burton was a good friend,” says Trujillo. “He would come and see me play with my bands Mass Mental or Infectious Grooves. He was very supportive of music as a whole, and he loved music that was driven by bass. I looked up to him, because he’d been through so much in his life.

“He kept a positive frame of mind through everything, and I admire that tremendously. He was very good with my kids, too. He would encourage Tye to play, and to study piano and theory, because that was what Cliff did. Tye took that in, and studied, and it made him a better musician. Ray was like that with everyone.”

So how do the members of Metallica look back on their fallen bass player, so long after his departure?

“It’s about looking back and being thankful for what he brought them,” says Trujillo. “Cliff was wise in a lot of ways, and very musical. He had a knowledge and a palette of music that was very broad, so he would have been teaching them classical to Lynyrd Skynyrd to punk rock. He brought all those ingredients into Metallica.”

“I always believe that everybody brings something into Metallica: it’s the sign of a great band. They learned a lot from him, and they looked up to him, and they celebrate him with every show they do and every song that they play that he was a part of. They feel that from the heart.”

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.

“I asked him to get me four bass strings because I only had a $29 guitar from Sears”: Bootsy Collins is one of the all-time bass greats, but he started out on guitar. Here’s the sole reason why he switched

“I got that bass for $50 off this coke dealer. I don’t know what Jaco did to it, but he totally messed up the insides!” How Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan went from buying a Jaco Pastorius bass on the street to fronting one of hardcore’s most influential bands