Cleopatrick's Luke Gruntz: “We want to try and give kids something enticing to belong to in guitar music”

The hard-riffing six-stringer talks mosh pit meltdowns, his “fighter jet” pedalboard and why he loves “stupid” guitar parts

Canadian duo Cleopatrick are updating rock music by stealth. Listen to tracks like The Drake, Family Van or 2018’s Hometown and you’ll hear a duo that live the ‘less is more’ maxim – producing the sort of riff-laden racket that can dissolve big rooms into a seething mass of sweaty bodies, wailing feedback and thundering subs.

Guitarist Luke Gruntz and drummer Ian Fraser hail from Cobourg, Ontario and met aged four. They both got guitars for Christmas a few years later and spent their intervening years developing a unique musical hive mind that has a strong sense of itself.

Gruntz learned the entire Hendrix catalogue but takes pride that you can cover all his songs on two strings; he ponders insecurity and modern masculinity amid tones that could level a parking lot; and he talks like a born romantic but refuses to write love songs.

Indeed the only rock rules that seem to apply here are that big riffs are nice and that bad names make good bands. Ahead of their forthcoming debut, Bummer, we spoke to Gruntz about his fighter pilot rig, “stupid” guitar playing and why space travel’s loss is rock’s gain…

Do you remember when you first realized you wanted to play the guitar?

“Yeah. I was in my basement. My parents were doing some spring cleaning and they had pulled out a tent and set it up for me and my little brother to play in. At the time, I knew I knew what music was, like I my dad had showed me AC/DC, Dean Martin and Roy Orbison, and all this stuff that I really loved.

“And, it sounds so funny, but I didn't realize that music was coming from people! I thought that it just lived on these these discs and these little cassettes. So we were in this tent, and I remember hearing an AC/DC song and I poked my head out and my dad had put on this old VHS tape of AC/DC playing in Paris.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I had butterflies, hearing this song that I knew, but seeing people really perform it. I remember like asking my parents like, 'Is this their job?' And they said, 'Yeah!' And then immediately, I knew, I was like: ‘That's got to be my job!’”

You and Ian (drums) both got given guitars when you were pretty young. When did you start to feel comfortable in your own skin as a player?

“For the longest time, I just kind of liked whatever my dad and my guitar teacher liked. Then slowly, I started to get into the blues/pentatonic type stuff and had this insane obsession with Jimi Hendrix. That still hasn't really faded.

“He doesn't necessarily inform my songwriting very much now. But as far as learning guitar, there was this one summer before the first year of high school where I was particularly anxious and I went from like a novice guitar player to being good at guitar by the end of that summer, because every day I played for hours.

“I used to be able to play along to every single released Jimi Hendrix song, every little bit of the solo. I'm sure it wasn't quite as good, but it felt amazing! That helped me develop this style of not thinking so much about theory and more trying to play things that structurally felt interesting – and also just playing with that abandonment.”

I couldn't find that in modern guitar music – bands that could elicit that kind of primal feeling in me

How do you characterize your sound or approach to the guitar now?

“I don't think too much about it. But I know that I write in the most simplistic terms possible. I actively analyze my parts and try and make them simpler. I love when something feels really clunky or stupid or almost comedic.

“That's what's the most like 'me' – when a guitar part is almost funny. I love seeing people covering our songs online, because you can genuinely do almost every song on the top two strings. So I don't know, maybe style is considered ‘stupid’!”

Hip-hop has had a big part in forming the Cleopatrick sound, too. What did you take from that as a guitarist and writer?

“I think that came partially just because after this Hendrix phase, I was searching for music that felt a little bit badass in like a modern way, you know? Obviously, Hendrix, it's old recordings, it doesn't necessarily have that same punch and, lyrically, I don't really relate to a lot of it.

“I couldn't find that in modern guitar music – bands that could elicit that kind of primal feeling in me. Whereas when I listened to hip-hop, there was so much more like, anger, and this juvenile mentality and confidence and swagger. And also, just blunt honesty – lyrics in plain language. That really attracted me as a songwriter.”

“When we started this band, and we couldn't find a bass player in our town. That's why we're a two-piece. So I have this pedal setup where I have this low sub-bass that I can toggle on and off at any moment.

“With that, suddenly, songwriting it felt like there was only really four layers I had to work with: vocals, drums, guitar and bass.

“[I realized] it’s almost the exact same formula of of most of my favorite hip-hop: just grimy drum loops and some sort of melodic loop underneath vocals and bass. Suddenly that kind of unlocked this fun challenge in our songwriting. Trying to write songs as if they were beats [and layers] on on a laptop.”

When did you hit on that idea? Taking that layered hip-hop production into guitar music…

“That wasn't completely discovered until near the tail-end of The Boys EP [2018]. We wrote Hometown and Youth and those two songs are like me realizing the potential of being able to turn on and off the bass at given moments, or even just stop playing, like [the drums] in the pre-chorus of Hometown.

I think to the kids it's too easy to think that playing guitar is not cool, because you just see old people doing it. And that's still what's promoted

“We like to call it ‘false momentum’: it's as if something bigger is happening, but really something's being taken away from the listener, and then returned to them.

“So now this whole new record, and the three singles that we have out there are all based around this, like, hip-hop mentality. That's probably another reason why I keep things so simple [on guitar] is just to really put the focus on the part that I have the most control over, which is what I'm saying.”

Tell us about the New Rock Mafia collective that you’re involved in. What is the thinking there?

“It’s funny, I feel like every time I'm asked about it, I kind of define it differently. But it's supposed to be an open-ended title that any band that feels like they're a part of this new type of rock music can associate themselves with. It really came from feeling like what we're going for is different from what people are expecting from guitar music.

“So yeah, NRM is like a collective started by three bands that are like happened to be really close in proximity here in Ontario: Ready the Prince, our band Cleopatrick and then Zig Mentality.

“And we all just kind of have the same ethos. We want to try and give kids coming up something enticing to try and belong to in guitar music. To help them feel like you don't have to align yourself with the old guys that are still around, still topping these these playlists and radio charts.”

Yeah. It’s ‘classic rock’ for a reason, but standards change – some would argue rock’s got a sexism problem, a race problem. Even a lot of ‘new’ rock is really just the old rock played by younger people.

“Yeah, that's exactly it. I think to the kids it's too easy to think that playing guitar is not cool, because you just see old people doing it. And that's still what's promoted. Hip-hop's been around for a long time now, too. The old guys that started it off still have massive respect – and that's really not what this is about. But things need to be reborn.

“NRM is not supposed to be like coining a genre term or anything corny like that, but it is supposed to be a way to separate what kids are doing versus what's been done. So we're putting a lot of focus into production.

“Our end goal is to be able to inspire a new sound that’s more in line with what's possible today – and hopefully make more people pick up guitars and start bands.”

You document your thoughts and experiences in the band very clearly in your lyrics. For instance, The Drake, which recalls the time your high school bully came along to a big show. Why do you take that route?

“Yeah, well it’s like you mentioned about the weird sexism and male dominance in rock music. I just can't write those kinds of songs, even love songs. It's just such a slippery slope and so much of it has been said.

“So all of our songs are about much more personal things that I hyper-analyzed! So The Drake is kind of about confidence. It’s a story of this night when we were playing our first big show in Toronto, after some Spotify playlisting.

“Right before we go on stage, like out of a movie, these guys walk in and one in particular was just this shithead that bullied me in high school, literally 'The Boys' archetype.

“I guess he'd never been to a rock show before [because] some of our friends started a mosh pit and he just got into full self-defense mode. He thought like six people were trying to fight him, simultaneously! He knocked one of our friends to the ground and it was just insane. But, in my anxiety, I just kept playing and watched it unfold in front of me.

“So that song kind of looks forward to the day where I realize I have the power to kick him out. But for this whole record, I challenged myself with not hiding behind any fake narrators or big analogies to make things feel less vulnerable.

“A lot of the album is about, being – or trying to be – a man, but defined in a way that I like. Not trying to be the classic 'man'. And just struggling with that inner turmoil and anxiety and these things that often affect me.”

Again, that’s something that hip-hop does well that you don’t see in rock. Someone like Kendrick Lamar, for instance, attempting to figure out who they are against the backdrop of all these tropes and stereotypes.

“Yeah. I think I see it as an interesting opportunity. It feels like there's a gap to fill in rock music [between] these preconceived notions of what it should be. So it's kind of this Trojan horse thing. Our songs are all fun, and they're mosh-y and you can be having a beer and jumping around, like, they feel really fun.

“But I have this opportunity to endow them with some real meaning and some real honesty. I have seen kids relating to it and it's given me more confidence to do it more openly. And I think it's cool that rock music is at this point where you can, you can slide messages like this in there and some people don't even realize what they're singing along to.”

The Les Paul's been the one for a long time. I think I got it because I was obsessed with Hendrix, but I didn't want it to show it, so I went the other route!

In the video for The Drake you're playing a Les Paul. Is that the usual choice for you?

“Yeah, it has been. Though my Les Paul's fucked my shoulder up, so I might start using this SG I got, which is like 10 times lighter. It looks dope and it sounds dope and I think it'll just be healthier for my spine!

“But the Les Paul's been the one for a long time. I think I got it because I was obsessed with Hendrix, but I didn't want it to show it, so I went the other route! I never really thought about it until this year, when I was like, 'I guess I'm a Gibson guy.’”

What about the other gear in your setup – how did you build your ‘automated bass player’ and the rest of your rig?

“I’ve been playing through this Vox AC30 since my high school bands. I've always liked pedals and I think I Googled for like 20 minutes and someone online said that Vox’s handle pedals well. And I love it.

“As far as pedals go, my 'board looks like the cockpit of a fighter jet, but it's not really that complex – it just has a lot of lights going off. I’ve always played through one fuzz pedal, which is EarthQuaker Devices’ Cloven Hoof fuzz. I got that for my birthday one year – shout out my mom!

“Then I've slowly kind of built up this rig. I have an A/B/Y splitter that I use for the ‘bass’, which is just my guitar signal, clean-split to a lower octave pedal, with some EQ-ing to make it sound more like a bass.

“Then there's a little fuzz pedal and it’s into a 2x15” bass cab. I just crank up all the low-end and cut all the highs in it. It sounds like a big fat hip-hop 808. As far as guitar, I have a reverb pedal and I do a bunch of Whammy stuff just because I only play with one guitar on tour, so I just have the Whammy to change tunings and stuff.

“And yeah, that's really it. There’s some chorus, but pretty much every pedal has like one song it's used in and then it's off for the rest of the night, except for the fuzz and the reverb.”

You committed to making music your career from a really early age. Do you ever think about what life would look like if it wasn’t for the guitar?

“It's tough to say. Growing up, I wanted to be an astronaut, but I'm colorblind, so apparently I can't be an astronaut. Then I wanted to be a magician. But I found out magic's not real, so that kind of bummed me out and I crossed that one off the list. And I also wanted to be Spider-Man for a bit. But that one doesn't work, either.

“So realizing that you could be a musician, it felt like the adventure of an astronaut, the magic of a magician, and the responsibility of a superhero combined! It made all of those things seem possible. It's just been so fulfilling and so meaningful for me. I can't even fathom who I'd be without it.”

- Bummer is out now via Nowhere Special Recordings.

Matt is Deputy Editor for GuitarWorld.com. Before that he spent 10 years as a freelance music journalist, interviewing artists for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.

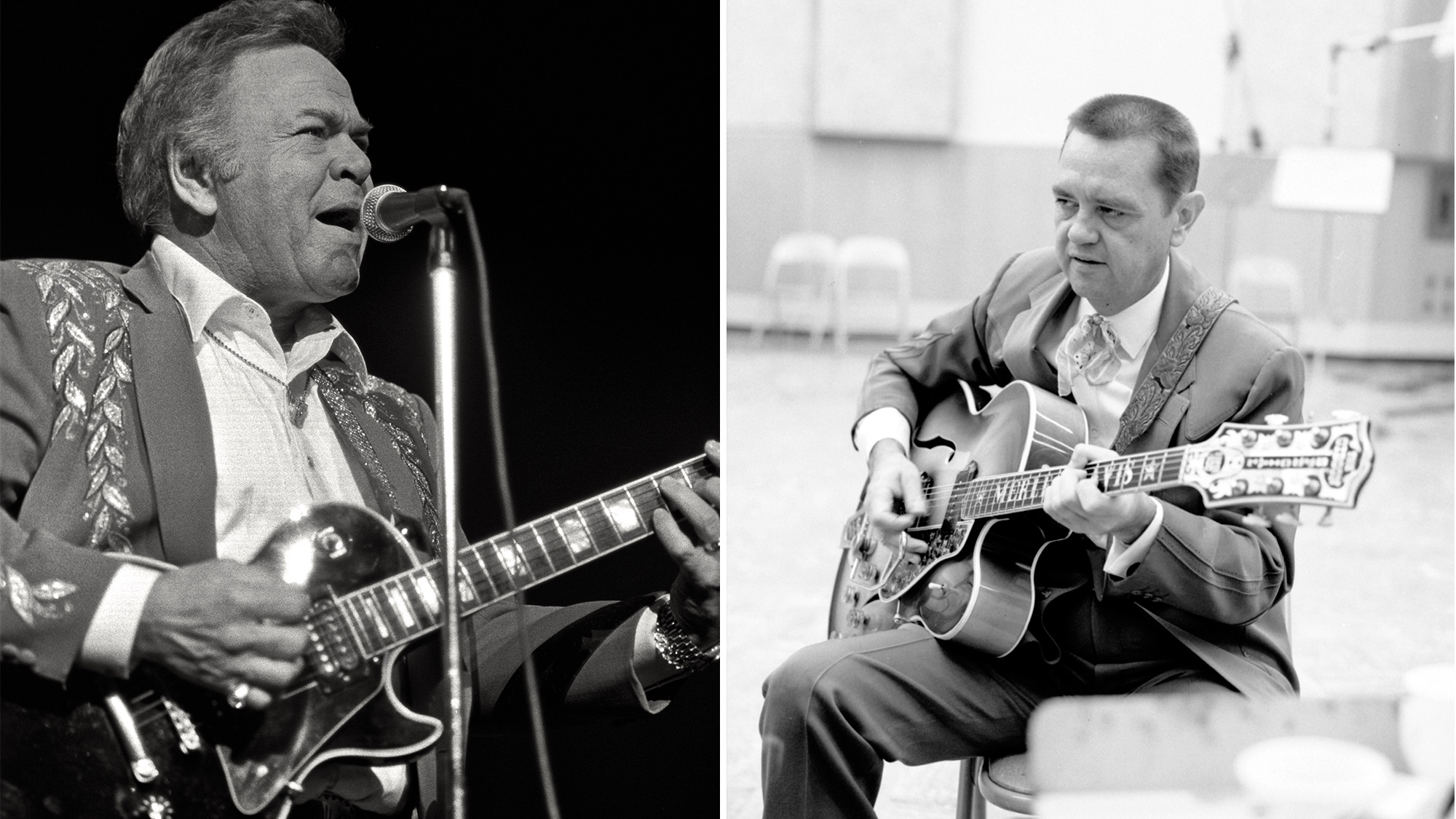

“I said, ‘Merle, do you remember this?’ and I played him his song Sweet Bunch of Daisies. He said, ‘I remember it. I've never heard it played that good’”: When Roy Clark met his guitar hero

“I asked Marcus to sing on it. As amazing as he is on bass, I think he’s underrated as a vocalist”: Having earned lofty status in bass-hero circles, Marcus Miller lent his vocal chops to Hadrien Feraud’s solo album