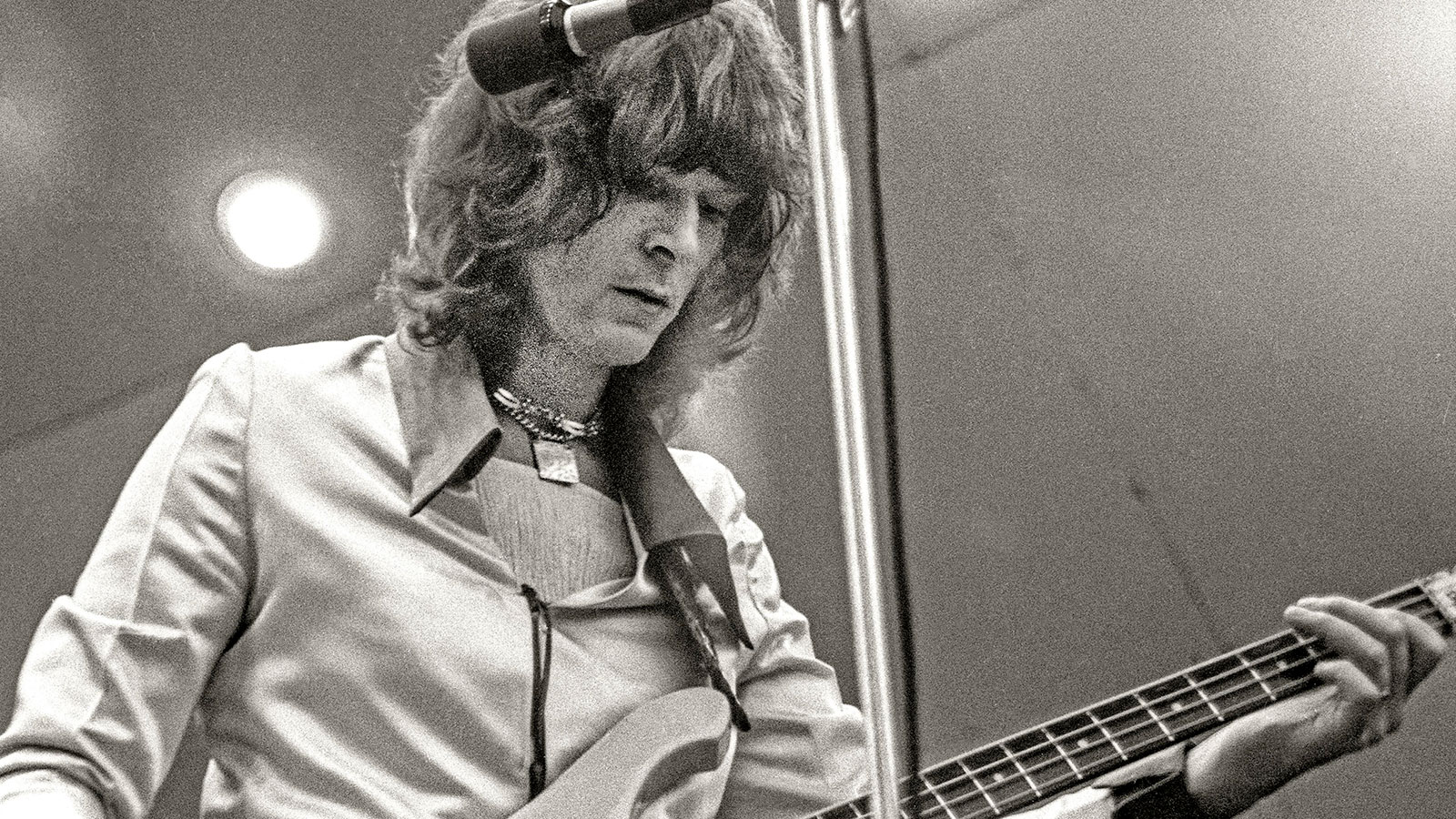

Remembering Chris Squire – the bass pioneer who redefined the instrument in the ‘70s with prog icons Yes

Seven years since his death and half a century since his band Yes released their masterpiece, Close to the Edge, the influence of Chris Squire is felt as keenly as ever

Bass players with dazzling technique and a tone that leaps from the stage – or, as is more likely, from your laptop speakers – are commonplace these days, fortunately for us.

We love a thuddy Motown bass guitar part as much as the next James Jamerson fan, but it has to be to everybody’s benefit that the bass is no longer hidden in the mix in most genres of popular music.

We have an audible voice these days, and one of the bass pioneers who enabled this fortunate transition was Chris Squire of Yes, whose tones were completely new and disruptive in the late Sixties to a degree that we can barely comprehend today. It’s important to grasp this, though – so important, in fact, that Squire deserves the cover of this magazine many times over.

As many of the musicians who have spoken to us for this month’s feature and for many previous Squire celebrations will tell you, no-one sounded like him when he first entered the limelight around 1970 – apart from one other bassist: Squire’s own hero John Entwistle of The Who.

Even The Ox, who predeceased Squire by 13 years, relied more on overdrive and volume than his lifelong admirer, whose tones were born from a different necessity, as we’ll see.

The bare bones of the Squire saga are reasonably well known. Born in Kingsbury, London in 1948, he discovered his musical muse in the Kingsbury church choir, where he was fortunate enough to be trained by the choirmaster Barry Rose – “the shining star of British church music at that time” as he later described him.

Interviewed by his fellow bassist Nick Beggs, Squire added: “My mum wanted me to be in the cub scouts and I fucking hated it, but my best mate said, ‘Tell your mum if you join the choir you can make two shillings and sixpence [about £2 or $3 today] for a wedding on Saturdays’...

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“When Barry Rose came to our parish, he threw out all the male voices and kept just six. And I was one of the six he kept. I was a soprano. Within two years we became the most important choir in England. Choir practice was supposed to be Wednesday and Friday nights for an hour, but he inspired us to be there every night of the week for five hours.”

“Rose taught us a lot about the relationship between vocal lines and bass-lines in a choir setting,” Squire told BP’s Brian Fox, “and I think I adapted a lot of that knowledge into playing bass and singing. I’ve always been very aware of the relationship between the bass and the top melody line.”

The church choir experience was more than just musical rehearsal for Squire: as he explained, it taught him the value of practice, the structure of classical music and how to work within a group.

I’d never heard a bass player play with such clarity. He always had it, right from day one

Rick Wakeman

This understanding paid off in spades when the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the Who landed squarely on the British music scene: by 1965 Squire was working in a music store, where he acquired a Rickenbacker bass.

“Playing bass came about when I was about 15 or 16 and was at public school. My mate was quite a good classical guitar player and we formed a little band. He said to me, ‘You’re tall with big hands – you should play bass’... so that’s how I became a bass player.”

Of the new wave of bass players, Squire was most impressed with Paul McCartney, Jack Bruce, Bill Wyman and John Entwistle, and soon began to play with a series of small-but-promising bands: first the Selfs, then the Syn – where he formed a strong bond with drummer Martyn Adelman – and later Mabel Greer’s Toyshop, influenced by the first stirrings of psychedelic rock.

The last of these introduced him to singer Jon Anderson, with whom he agreed to form a new project, and so Yes was born.

Connecting Anderson’s understanding of symphonic music with Squire’s choral background and both musicians’ love of rock’n’roll, the duo added guitarist Peter Banks, drummer Bill Bruford and keyboardist Tony Kaye.

Banks was replaced by Steve Howe after the Yes (1969) and Time And A Word (1970) albums, and the new line-up had their first major hit with The Yes Album, a US Number One hit in ’71. Kaye was replaced by Rick Wakeman, who recalls his first meeting with Squire.

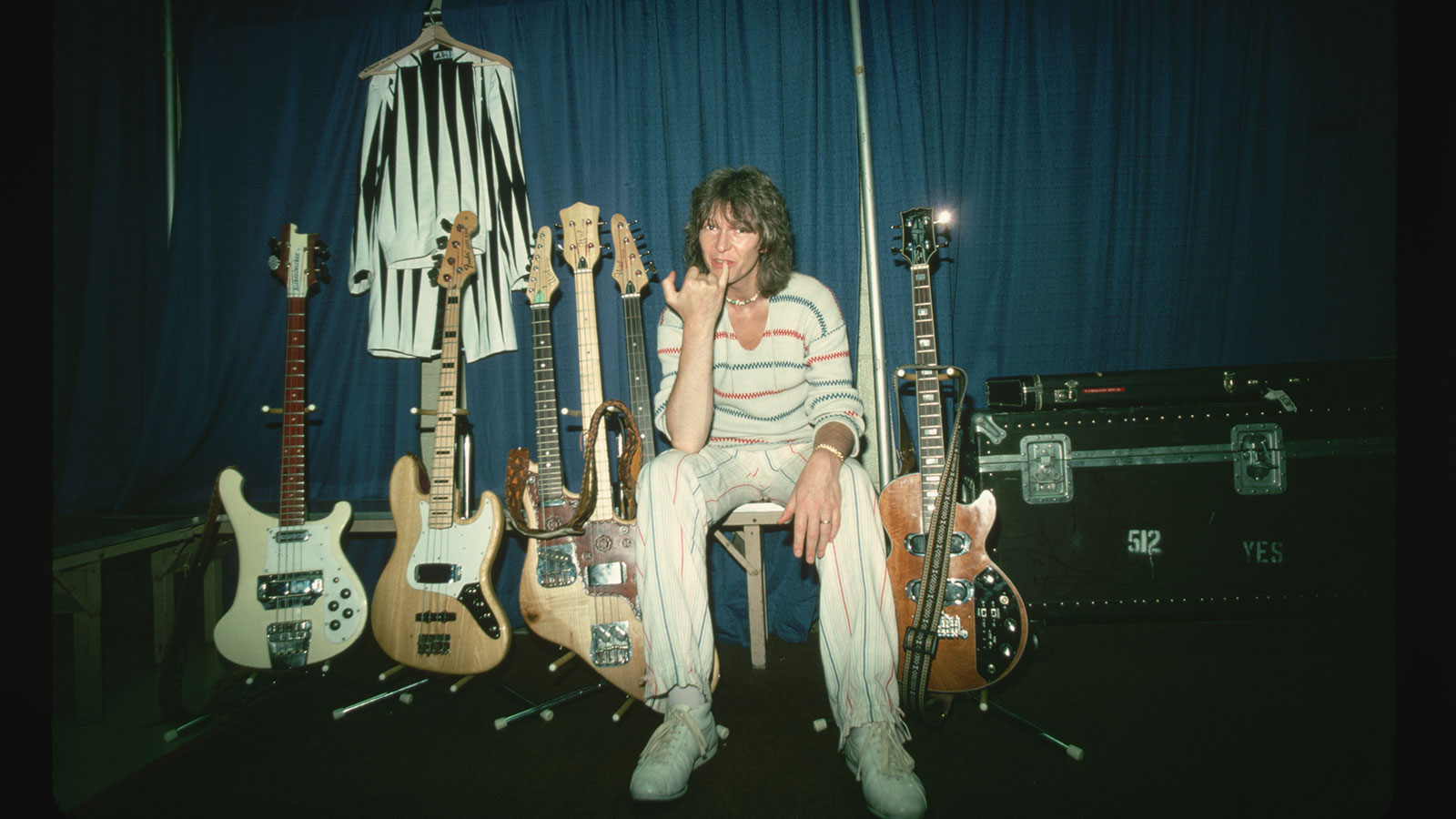

“The first time I saw Yes play, I thought it was the most unusual line-up I’ve ever seen,” he says. “In the early to mid-Seventies, rock bands usually had a guitarist who would use a Marshall stack and a Fender Stratocaster or Telecaster, and the bass player would have a Fender bass and a Marshall stack.

In Yes, if anyone had told anyone else how to play, it would have ended up like an episode of CSI. We all gave each other ideas of what to play on pieces, which was always fine – but telling somebody what their sound should be like would be tantamount to death

Rick Wakeman

“In Yes, though, Steve Howe was using a little Fender Twin amp and a Gretsch guitar, and Chris had Sunn amps and a Rickenbacker bass. I thought ‘What’s that all about?’, because in those days, you couldn’t give Rickenbacker basses away. I used to go to a guitar store in South Ealing and they had loads of them on the wall for sale, second hand. They couldn’t shift them!”

Despite his unorthodox setup, Squire impressed Wakeman greatly. “I’d never heard a bass player play with such clarity. He always had it, right from day one,” he remembers. “When I spoke to him about it, he told me that the midrange controls on his amp had stopped working, so he wound the treble and the bass up, which gave his sound all the power but all the clarity too.

“That sound really played a big part in how he played the bass, especially when he played lead lines: he could do so much more than most bass players, along with John Entwistle. It was fascinating, because he kept those Sunn amps for years: even when the money came rolling in and he could afford to have them mended, he never did.”

Two things come to mind here. First, so much of Seventies bass lore might just be attributable to a broken mids control on an amp. Second, if Squire’s bass tone was so unusual, did any of Yes ever suggest to Squire that he amend it?

“Um, no!” chuckles Wakeman. “In Yes, if anyone had told anyone else how to play, it would have ended up like an episode of CSI. We all gave each other ideas of what to play on pieces, which was always fine – but telling somebody what their sound should be like would be tantamount to death.

“Also, we really liked how Chris played: it contributed so greatly to the overall Yes sound. You could hear everything that he did, and not just because he played so deafeningly loud. I used to play near him on stage, and I had to get him to angle his cabs away from me.

“He was very aware of his frequency space, and he also know when not to play, which is not something that many musicians have. If only one bass note was needed, that’s what Chris would play.”

He was always late, and it used to drive everybody mad. We missed numerous flights, and we’d often arrive at concerts just in time for soundcheck. But he’d just amble in and go, ‘Hello!’

Rick Wakeman

Wakeman has remained with Yes – with several extended breaks here and there – for the rest of the band’s existence, while Squire remained throughout as the final founding member. In that time, the two men became close friends, on stage and off.

“He was completely unique,” muses the keyboard veteran, “and one of the things that’s hard for bass players is having a unique sound. It enabled us to include bass solos in pieces such as Heart Of The Sunrise.

“He used to do an amazing solo with [drummer] Alan White: I used to go off to the side of the stage, where I had a little picnic table. I’d have a cup of tea and three digestive biscuits, and I could time it exactly: by the time I’d had those, it was time for me to go back on stage for the finale.”

Asked what sort of person Squire was off stage, Wakeman explains: “Chris had so many personalities some of which were just wonderful and some of which were infuriating! One of the latter, as is very well known, was his timekeeping – not musically, but turning up when he was meant to. He was always late, and it used to drive everybody mad.

“We’d be waiting in the hotel foyer for him to come down, and we missed numerous flights, and we’d often arrive at concerts just in time for soundcheck. But he’d just amble in and go, ‘Hello!’ That was Chris. He never apologised.

“I remember once, around 2000, we played London and then we had to play Nottingham the next day. But Chris went off to lunch in London on the day of the Nottingham show with a business colleague, and he turned up in Nottingham so late that we were 90 minutes late going on stage. He told us ‘I didn’t think there’d be quite so much traffic!’ That was the one occasion where I did feel that one of us might do some bodily harm to him...”

“In the end, though, that’s who he was, and we had to live with it. It was well worth it for all of his other great attributes. He had a good sense of humour and was a great conversationalist. He never ran out of things to talk about, and he was a great singer, a great writer. I was pretty close to Chris: we had a very good bond, and we always had a hug at the end of every show, whether we were saying to each other ‘You were great tonight’ or ‘What went wrong?’”

By 1980, Yes had scored no fewer than seven consecutive gold or platinum albums, varying in style from all-out progressive rock to lightweight AOR, the latter sound peaking with their huge 1983 hit Owner Of A Lonely Heart from the 90125 album.

Each was powered by Squire’s speedy, trebly lines: through the Eighties and into the Nineties he became a profound influence on a whole set of bassists, from Geddy Lee to Les Claypool of Primus and Dug Pinnick of Kings X.

Along the way, Squire released a line of solo projects, from the Fish Out of Water album in 1975, via a project with his eventual successor Billy Sherwood called Conspiracy and a short-lived trio with White and Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page called XYZ, to a sequence of recordings under the name Squackett with Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett.

This magazine supported him through many of these sideline projects, as long-time readers will recall, and unlike many virtuoso musicians, he never tired of talking about bass – whether that meant tones, gear or techniques, as we explore here.

Yes continued to release albums into the 2000s, with Squire indulging a long-held ambition in 2007 by releasing a solo record called Chris Squire’s Swiss Choir. Married three times with five children, he lived a full life that was only cut short by a battle with leukemia: he died at the age of 67 on June 27, 2015, no doubt with at least a decade of music still in him.

Musicians such as this leave a serious legacy, of course, and although Chris Squire’s bass playing is just one of his many talents, we meet bass players on a virtually daily basis who ask about his tone, his technique and his all-round approach to life. We raise a glass to him in this feature: but go and listen to his music in his honour. That’s what we’ll be doing – for decades to come.

- Yes will be playing dates on the 50th Anniversary Celebration of Close to the Edge Album Series Tour through 2022 and ’23. Head to Yes for dates.

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.

“I asked him to get me four bass strings because I only had a $29 guitar from Sears”: Bootsy Collins is one of the all-time bass greats, but he started out on guitar. Here’s the sole reason why he switched

“I got that bass for $50 off this coke dealer. I don’t know what Jaco did to it, but he totally messed up the insides!” How Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan went from buying a Jaco Pastorius bass on the street to fronting one of hardcore’s most influential bands