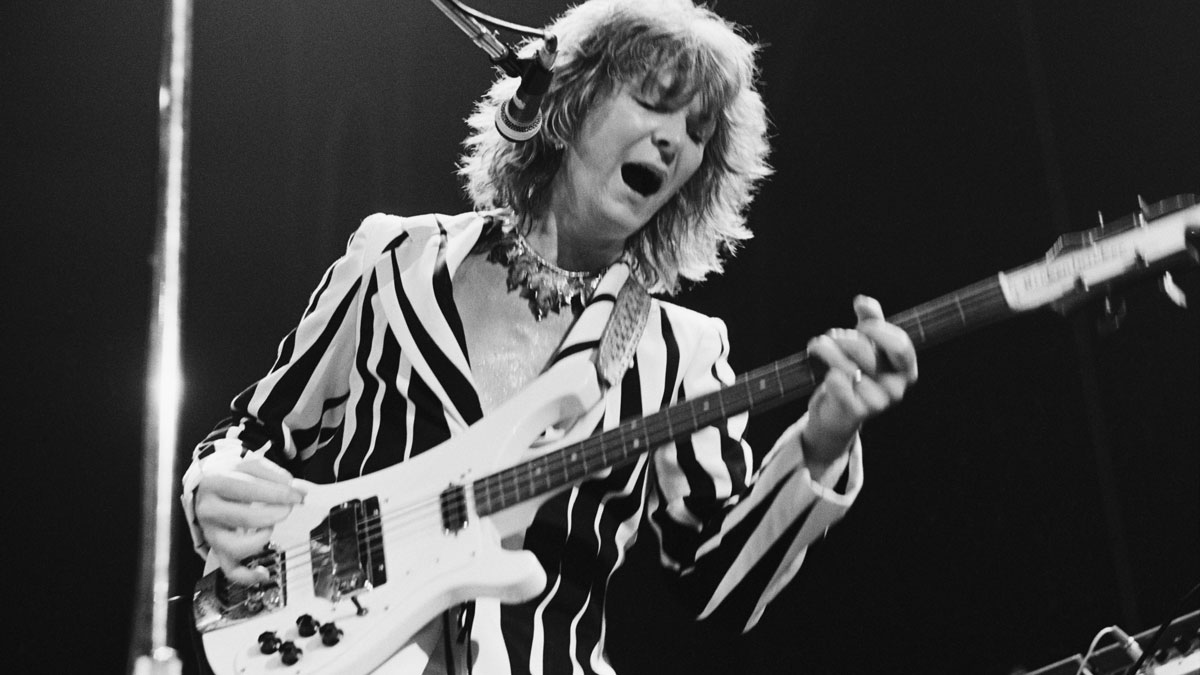

Chris Squire 1948-2015: the story of the hugely influential Yes bassist

Paying tribute to the celebrated progressive pick player

It was a troubling announcement that caught the music world by surprise in May of 2015: Chris Squire of Yes had been diagnosed with a rare form of leukemia and would be forced to take a leave of absence from the band’s busy touring schedule.

“This will be the first time since the band formed in 1968 that Yes will perform live without me,” said Squire, who co-founded the group and was the only member to appear on every one of Yes’ 30-plus studio and live albums.

After a temporary replacement had been chosen, the band’s website asked fans to send Chris good wishes for a speedy recovery as he underwent treatment. Yes devotees were rattled but hopeful; surely he would recover and get back to business.

But just two months later, Chris Squire was dead. It seemed impossible—the ever-present progressive pioneer that had grounded, glued together, and guided Yes for nearly half a century was gone.

A musician of incalculable talent, Squire was a game-changer for bass players around the globe. With a signature sound and a brilliant sense of syncopation and counterpoint, the big man nicknamed “Fish” was the cornerstone of Yes’ sonic appeal and a fearless force in its live-show spectacle.

Armed with his Rickenbacker bass, Chris earned membership in that small, elite club of bassists who molded originality, technique, and imagination into a playing style that had not existed before.

He cited Paul McCartney, Jack Bruce, and Bill Wyman as influences, but it was the Who’s John Entwistle that lit Squire up the most. He emulated Entwistle’s trebly roundwound sound, filtering it through his own intuition and the keen ear for classical harmony he had developed as a young choir singer.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

With an aggressive pick attack and machine-like precision, Squire’s bass playing quickly became one of the most dominant and recognizable sounds in rock in the early 1970s.

Along with his enormously talented bandmates, including singer Jon Anderson, guitarist Steve Howe, keyboardist Rick Wakeman, and drummers Bill Bruford and Alan White, Yes racked up an incredible seven consecutive gold or platinum albums in its first ten years, a mind-blowing feat that powered the band forward for decades.

Early years

Christopher Russell Edward Squire was born in the London suburb of Kingsbury in 1948. His mother enrolled him in the Cub Scouts when he was a young boy, but Chris hated it; when a friend told him he could make money singing in their church choir, he discovered not only his ticket out, but his inner musical talent, as well.

Trained by renowned choirmaster Barry Rose (Chris later referred to him as “the shining star of British church music at that time”), he was handed the road map for his future: “I learned from an early age the importance of practice and making a unit that was fired up to be the best,” said Squire.

He was in his early teens when the Merseybeat sound swept Britain, and when the Beatles, the Stones, and the Who arrived on the local scene, Squire found his calling. At 17 he landed a job selling guitars in a local music store, where he used his employee discount to purchase a brand new Rickenbacker bass.

The burgeoning music scene also brought with it a new drug culture, and Squire began experimenting with LSD. After a bad acid trip in 1967, Chris withdrew from life and hunkered down in his girlfriend’s apartment for months. This would turn out to be the most important period in his bass development; he practiced relentlessly and raised his playing level by great leaps. He vowed to never use LSD again, and emerged from the experience ready to face the world with his Rickenbacker at the ready.

Squire joined local bands, including the Selfs, the Syn, and Mabel Greer’s Toyshop. During his stint with Mabel Greer, he met the person who would co-charter the course of his new musical journey: Jon Anderson. They met at London’s La Chasse club where Anderson worked, introduced by the club’s manager. “It was right over the famous Marquee Club in Soho,” recalls Anderson.

“I was always looking for a good band to work with, so I went over and spoke to Chris, and we just hit it off right away.” The two bonded over their mutual interest of vocal music, particularly bands like Simon & Garfunkel and the Fifth Dimension. “We talked about music in general and had the same sort of musical aspirations,” says Jon. “We went straight back to his apartment and wrote a couple of songs together, and from that moment, it was a question of, okay, how do we get this thing going?”

Just say Yes

Anderson and Squire plotted out the course of the group. They quickly re-shuffled Mabel Greer’s lineup, brought in drummer Bill Bruford and keyboardist Tony Kaye, and then honed their musical vision. “We both felt that we didn’t want to make pop music, because we were too old, and we didn’t look like a pop band,” laughs Anderson.

“So we just talked about crafting music for stage and putting on a great show. And that was our main goal, from the beginning. I was studying a little about symphonic music, and Chris had a lot of choral music background, so we talked about that. We decided that if we get a band going we’ve got to have singers—it can’t just be one voice with a backup band—and it’s got to be a fusion of all these musical ideas. Oh, and Mabel Greer’s Toyshop is such a long name, can we not get a short name?” says Jon, laughing.

Anderson also marveled at Squire’s ability. “He had his act together on his Rickenbacker. The sound of his bass was amazing. When we started writing he would use his bass very much as a main instrument, like a solo part. The guitarist at the time, Peter Banks, was sort of backing up ideas, and then he would jump off and do solos, but the bass was the central key to the musicality of the songs we did in those early days.”

Squire also had an innate ability to interpret Anderson’s songwriting ideas, and he created bold bass statements to support his songs. “I hardly ever said anything to Chris about what he should play,” says Jon. “He always seemed to naturally go for a very powerful driving part, and then when I would start to sing he’d go very melodic and underpin what I was singing. By the time we did shows and concerts, there was this beautiful soundboard that was created, generally through Chris’ understanding of bass and my vocal. The concept of those together within Yes was that edge of magic that was different from most bands of that time.”

When Banks left Yes after two albums, Squire called up guitarist Steve Howe on Anderson’s recommendation. Howe was a perfect match for Squire’s style of bass playing.

“Chris had invited me to play with the band,” Howe recalls. “He was really a formidable bass player who was kind of thinking different, outside the box, as we say now. Most bass players were just playing the roots. With Chris, it was like he jumped over the fence and saw it from the other side. His way of thinking was that classical music is more interesting, jazz music is more interesting … why not rock?”

Howe connected with Squire’s playing brilliantly. “When we started working together, we aligned. We played the same things, or he’d play something because I did something. We played off each other.” Howe points out that Squire’s playing raised everybody’s game in Yes.

“Bill Bruford and Chris were a very powerful early force, and they both made each other sound great. Chris certainly affected my playing because he was capable of a lot more than most bass players were at that time. And also, he swung. He rocked, he swung, he pounded.

“Like me, he was trying to use all the techniques that you could get out of an instrument; his was the bass, mine was the guitar. It was great. He played up high, but I think we didn’t notice much at first because he was always convincing. When somebody’s playing convincingly, you don’t stop and say, ‘Oh god, the guy’s all the way up his neck,” laughs Steve.

“Chris was a very mobile player, but also, if you listen to the records, in the studio he was a very dynamic player. He didn’t play at one peak all the time, which can happen when you work onstage a lot. There were moments when his thoughtful, feely kind of playing was the key; we realized that we were all able to do that, and suddenly we were playing differently.

“And that was a real beautiful thing. Being part of the team, he added a tremendous amount. Not a lot of bass playing was as interesting before him.”

Big Fish

With Howe, Yes scored its first big hit with The Yes Album, which reached #1 on the U.K. charts. After keyboardist Rick Wakeman replaced Kaye in 1971, Yes broke out in America with the iconic Fragile and Close to the Edge albums.

“Chris was one of those rare musicians that pretty much refused to be influenced,” says Wakeman. “He was the ‘influencer,’ if there is such a word. He treated the bass guitar as more than just propping up the bottom end, and truly considered it to be a lead instrument that deserved recognition, and that’s what he gave the instrument.”

After the release of 1973’s Tales From Topographic Oceans and Relayer in ’74, creative differences began to cause cracks within the band. They took a well-needed hiatus, and everyone went to work on solo projects. Squire’s Fish Out of Water, released in 1975, showed off his songwriting and lead vocal skills in a big way. The album, a critical success, reached #25 in the U.K. and #69 in the States.

While his impeccable sense of time served him well musically, Squire’s concept of real time was less sharp. His tardiness was legendary. It was a source of frustration for some within in the group, particularly Bruford and guitarist Trevor Rabin, who replaced Howe in 1982.

“It drove Trevor crazy,” Jon Anderson recalls. “Everything was always, ‘Where’s Chris?’ But he was a very funny guy; he had a very dry sense of humor. He’d joke and say, ‘Yeah, you can always put on my tombstone ‘the late Chris Squire.’ And that sums him up, you know?”

Drummer Alan White offers his own take: “Chris would always say that he knew everyone was telling him to come early, so he just came when he thought he should come. And then he’d say, ‘I don’t like to wait for people,’ so that was his answer.”

Squire’s love of a good laugh was contagious. Wakeman recounts once turning the table on his mate: “During the Union tour, there was a moment in the show when through a trap door in the revolving stage, one of Chris’ bass guitars would be handed up to him. It appeared to be coming out of the floor, and it was a moment Chris loved, although he wasn’t that amused when I replaced the guitar with a giant inflatable fish on the last show. The audience loved it. And so did Chris when photos appeared everywhere!”

Perpetual changes

With all the ups and downs, regular personnel changes would become the norm for Yes; by 1983, the year the band scored its biggest commercial success with the album 90125, 14 different musicians had already come through the ranks. But Chris, the only bassist, had become in many ways the de facto leader of the group.

The band would never again reach that level of success, but Squire remained focused and steadfast on keeping the group working, writing, and recording. Yes released six studio albums in the ’90s and another three after that, touring constantly and retaining its huge fan base.

Squire also branched out with side projects on occasion, including the band Conspiracy, with guitarist Billy Sherwood (who is currently playing bass in Squire’s place on this year’s Yes tour), the short-lived XYZ with Alan White and Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page, and several recordings with Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett. In 2007, Chris returned to his early passion and released a solo album entitled Chris Squire’s Swiss Choir. But his work with Yes is what his legion of fans will remember him for the most.

“He had a fun life,” says Anderson. “He lived life very largely, and he became a rock & roll icon and celebrity, in the sense that he lived a wild life.”

Alan White ponders a Squire-less Yes: “Not many bass players had a tone like Chris. In fact, he set the standard for that kind of bass sound. He set the bar for a lot of people. It’s going to be very hard without him, playing onstage and not seeing that huge framework of a guy in front of me that was the foundation of the bass section. It’s not going to be easy to do that.”

Steve Howe fondly recalls a bonding moment he had with Chris a few years ago before a gig.

“Chris and I sat alone in a room and we just talked. Just two blokes in a room with a cup of tea and talking, and how we could make things better in Yes and things like that. And those moments we didn’t have enough of. I’m going to miss the opportunity just to have more one-to-ones with him.”

Perhaps Anderson sums up Squire’s legacy the best: “One of the great bass players ever. His musicality will be listened to over the years, and people will start to realize what he put into Yes music that made it very special. He was very harmonic and very melodic with his bass, and very, very unique. He was definitely one of a kind.”

Driving through the sound

Chris Squire recorded or performed with more than a dozen basses in his career, but he is most closely associated with the cream-colored 1964 Rickenbacker with which he created his signature style. Although many refer to it as a 4001, it was actually an RM1999 (serial number DC127), imported to the United Kingdom by Rose Morris, Rickenbacker’s official British importer in the early 1960s. Build-wise, it was identical to the 4001S, with dot fingerboard inlays, no body binding, and a single output.

Squire’s Rickenbacker, which he bought from his employer Boosey & Hawkes in 1965, had a Fireglo finish, similar to Fender’s sunburst. When the flower-power era arrived, Squire covered the instrument with flowery wallpaper, but he soon tired of the look and had a guitar tech remove it, which required shaving and sanding.

Chris covered the bass again, this time with silver reflective paper, and when he got bored of that, he asked the same tech to remove it. The tech applied a cream lacquer and suggested that Squire leave it that way.

After being sanded twice, the bass was lighter, and Squire would later say that this was a factor in its unique, bright sound. None of his other Rickenbackers—including the limited-edition 1991 4001CS signature model that was a virtual replica— sounded like Squire’s cream bass.

The instrument held up fairly well, until a stage accident required Squire to bring it to luthier Michael Tobias for repair.

“The work was done in the mid to late ’80s,” recalls Tobias. “If I remember correctly, the peghead had been broken off more than once. When I got the bass, it was hanging by a thread, and there was almost no glue surface left. The break was almost straight through under the nut. Because of the way Rickenbacker cut out the trussrod access, there wasn’t much area to re-bond. I got a new rod system from Rickenbacker and made a scarf joint so there’d be some area to glue. I recreated the original peghead with the proper wood, attached it, shaped it to the existing neck profile, and matched the paint.”

One of the RM1999’s notable quirks was its weak bridge pickup, which had a lower output and “tinny sound,” as Chris described it. “It was actually dead,” says Tobias. “I installed a new pickup from Rickenbacker, but Chris didn’t like it, so I put the old pickup back in. It would pick up a little from the working pickup and make some sound, but not on its own.”

Other basses in Squire’s arsenal included Fender Telecaster and Jazz Basses, a 4-string Chris designed with Jim Mouradian, and an MPC Electra 4-string. Squire also played Lakland and Yamaha 4-strings, a Ranney 8-string, and several models Tobias built for him. Perhaps the oddest bass Squire played was a triple-neck made by Wal, given to him by Rick Wakeman. Used on the Yes song “Awaken,” it featured doubled A, D, and G strings on top, a fretted 4-string in the middle, and a fretless 4 on the bottom.

Squire, who felt that certain effects were better matched with neck or bridge pickups, rewired his Rickenbacker with stereo outputs in the early ’70s. Onstage, he used a boatload of vintage effects, including Maestro Fuzz-Tone, TC Electronic Stereo Chorus Flanger, TC Nova Reverb, Boss OC-3 Super Octave, Mu-Tron III, and custom-made tremolo pedals. He played Moog Taurus bass pedals, eventually triggering samples from an E-Mu ESI2000 sampler.

Squire’s string choice was a standard-gauge set of Rotosound Swing Bass roundwounds. He nearly always played with a Herco heavy-gauge pick, attacking his strings either in front of or behind the bridge pickup, depending on the brightness he wanted. His picking technique was also unique: By holding the pick just barely in front of his thumb, he would hit the string first with the pick and then with his thumb a millisecond later. Squire said that the string’s harmonic was more pronounced because of “more contact with the human body.”

Chris used several rigs over the years, including Sunn amps and cabinets, Ampeg SVT-2 PROs, Ampeg 8x10 cabs, and a pair of Clair Brothers custom 6x12 cabinets built with each speaker pointed in a different direction, so that when they were laid flat Chris could easily hear himself wherever he was onstage. His original Marshall 100-watt amp and 4x12 cabinet, however, was a mainstay.