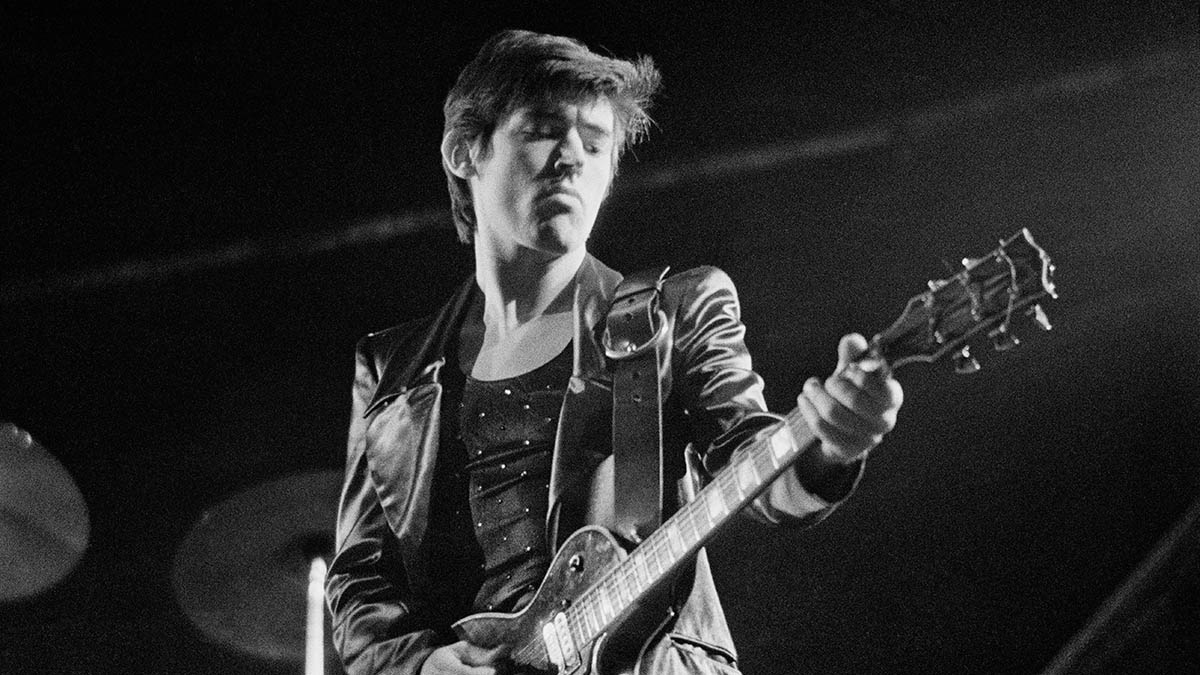

“Jimmy Page and Jim Sullivan were getting a lot of work, but I was always getting plenty of calls – and that increased after I did the Jack Bruce sessions”: The confessions of session pro Chris Spedding

The British session ace on being asked to audition for the Rolling Stones, producing the Sex Pistols’ early demos and recording Robert Gordon’s final album

Over a career spanning nearly 60 years, British session ace Chris Spedding has worked with pretty much everyone in the business. For US audiences, he might be best known for his long association with latter-day rockabilly legend Robert Gordon, who passed away in October 2022.

Gordon’s final album, which was released weeks after his untimely passing, Hellafied, sees Gordon and Spedding team up for one final go-around.

It was very sad news about Robert, who was just 75 when he died.

“I guess his health hadn’t been all that great for some time. I had a call from him when he told me he’d been diagnosed with leukemia, which was a bit of a shock. I think initially he thought he’d have a lot more time left, but then he was gone a few weeks later.”

It’s interesting that Robert’s work wasn’t self-consciously retro in the way that the Stray Cats were; he was actually creating a modern take on rockabilly when he broke through in the ’70s, with you and Link Wray in particular bringing a harder rock edge to the sound.

“Well, me, Robert and Link were all first-generation rockers; we weren’t reviving anything, you know? I think the attitude and the guitar sounds were much more modern, and in the ’70s that sat well with the punk and new wave audiences as well as traditional rock ’n’ roll fans. It was a real joy for me to play with Robert, to be able to play that straightforward rock ’n’ roll that we both loved.”

What was the situation with Hellafied? Was it old demos, etc.?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Some were done way back in Denmark where we had to abandon the sessions as the studio wasn’t up to par, but Robert recently listened back to them and thought we could salvage them with some new guitars and vocals. There were a few really old demo ideas as well that we used, but for most of the songs I ended up redoing my parts in the UK on Pro Tools and Robert would do his new vocals in the States.”

Reeling way back to the earliest days, was the intention always to work as a session musician or was there never any real gameplan?

“There was no gameplan at all. I just thought I’d like to be a musician. I’d been listening to all sorts of music – there was a period when I was really into jazz in the ’60s, which was how I got into the whole fusion thing with bands like Nucleus and playing with Jack Bruce, but my first love was really rock ’n’ roll, I guess.”

Was there a lot of competition for session work when you started in the ’60s?

“I know that Jimmy Page and Jim Sullivan were getting a lot of work, but I was always getting plenty of calls – and that increased, particularly after I did the Jack Bruce sessions and Nucleus. I suppose people assumed that if I was in a band like Nucleus, I must be a proper musician. [Laughs]”

What did you take to sessions in the late ’60s/early ’70s?

“These days I have about 20 guitars; back then I was playing a 1964 Gretsch Country Club, but I realized people didn’t really want the Gretsch sound, so I part-exchanged the Gretsch for a Telecaster.

“I didn’t realize at the time that I was really taking a step down there. [Laughs] There was no concept of thinking that maybe I could have both guitars – back in the ’60s you had one guitar. Eventually I got a Les Paul and a Strat and took those two guitars to every session.”

How did you deal with a session where you didn’t really like the song, the artist or whatever?

“You don’t know how something’s going to turn out – it could be the best thing you’ve ever done, you know? Sometimes you’ve never heard of the artist but then they go on to be huge. I’ve also done many sessions where I had really high hopes and they turned out to be disappointing. You just have to go in there with total commitment.”

Early on, you were in a band called Battered Ornaments, who managed to get the support slot with the Rolling Stones at Hyde Park in London in 1969. How’d you manage to pull that off, considering you weren’t really very well known?

“The show was put on by Blackhill Enterprises, who also managed Battered Ornaments, so we managed to score that plum gig.”

You were later asked by Mick Jagger to audition for the Stones – in one of those stories you probably got tired of discussing 40 years ago. Would he have thought of you because of that Hyde Park show?

“No. I doubt whether they were even conscious of me being in that band. I doubt I impressed anybody on that particular show. I think it was just that my name was getting around quite a bit by 1975. It took them about six months to call me, so I wasn’t that flattered anyway. [Laughs] I had a load of work booked at the time, plus I’d just recorded Motorbikin’, which I had high hopes for – justifiably, as it turned out to be a big hit single in a lot of countries.”

The release of Motorbikin’ really took things up a level for you in 1975.

“I wrote that after the band that I was in, Sharks, broke up and I came up with what was a new sound for me. I’d looked at the pop charts at the time and there was nothing there that I really liked, so I wondered what it needed. I decided to try to do something like the music that inspired me – Elvis, Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent.

“A retro kind of thing, which was also the way I was looking at that time, so when I did the UK music show, Top of the Pops, I looked and sounded completely different from everybody else – they all had blow-dried hair, flared trousers and platform shoes and I looked like I’d just got off a Harley-Davidson, so it worked well for me.”

People underestimate how good the Sex Pistols were as a band

I think that image was actually very much in line with the way a lot of punk bands looked a couple of years later, and – of course – you actually produced some demos for the Sex Pistols before they scored their record deal.

“I knew as soon as I heard the Pistols that they were exactly what the music business needed, and not a lot of people saw that in their early days. People will often say I played some parts on their demos, but that isn’t true. They did use my amps, but it was all them. People underestimate how good they were as a band.”

Hurt, released in 1977, was probably your highest-profile release. The guitar sounds were some of the best of your career. Was that mostly the Flying V?

“Chris Thomas, the producer, was a great asset in helping to get a really good sound on the album, and I think I had some very strong songs as well. It definitely got the most exposure of any of my albums. I think it was a mix of my Flying V, a Les Paul and an SG Junior into a Fender Deluxe Reverb. I don’t think there were any Fender guitars on that album at all.”

I never practice anymore. If I get a job to do – if someone sends me a song – I just wonder what the song needs to improve it

What kinds of things do you play when you’re sitting at home?

“I never practice anymore. If I get a job to do – if someone sends me a song – I just wonder what the song needs to improve it. I used to apply the thought, 'What would George Harrison do here?' until I realized it could have been George, Paul or John playing a part, so I guess now I think, 'What would the Beatles do here?'”

Of course, you got to work with Paul McCartney on Give My Regards to Broad Street in 1984. Is there anyone out there that you’d still like to play with?

“It would be nice to get a call from Bob Dylan!”

- Hellafied is out now via Cleopatra.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

“I knew the spirit of the Alice Cooper group was back – what we were making was very much an album that could’ve been in the '70s”: Original Alice Cooper lineup reunites after more than 50 years – and announces brand-new album

“Such a rare piece”: Dave Navarro has chosen the guitar he’s using to record his first post-Jane’s Addiction material – and it’s a historic build

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)