Charvel Guitars: Built For Speed

Originally published in Guitar World, March 2010

How a small California guitar parts and repair facility kick-started

the guitar custom shop revolution and became the premiere maker of super-fast guitars for everyone from Eddie Van Halen to Steve Vai to Warren DeMartini. Guitar World celebrates the storied history and glorious renaissance of Charvel.

Wayne Charvel unwittingly spawned a guitar custom shop revolution when he opened Charvel's Guitar Repair in 1974, in Azusa, California. The shop performed aftermarket customizations and sold parts that allowed guitarists, including an early customer named Eddie Van Halen, to build their own instruments. At the time, the major guitar companies didn’t offer custom work to the public, and they typically turned over artists’ modification requests to independent luthiers, such as Charvel. In that respect, Gibson, Fender and the other big firms helped independents like Charvel prosper. Ironically, the poor quality of those companies’ guitars during that era drove more business to the doors of Charvel and its ilk, as players sought competent luthiers that could turn their mediocre instruments into something special.

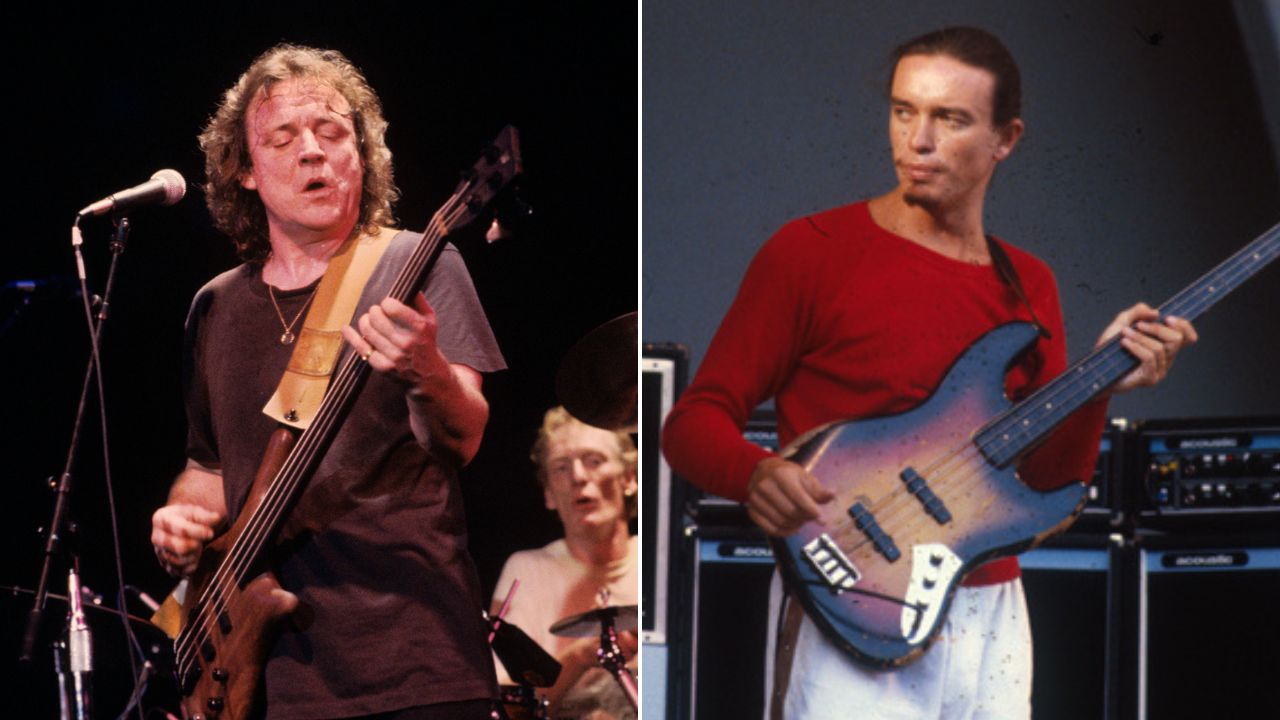

It didn’t take long for Southern California guitarists to appreciate the Charvel shop’s hot-rodded electronics and the superior playability that its modifications provided. By the late Seventies, when Charvel began to build its own guitars, the company’s aptly dubbed “superstrats”—with their flat, unfinished necks and large fret wire—had become synonymous with the rising trend of shredding. As the Eighties gave rise to virtuoso shredders, Charvel guitars could be seen in the hands of players like Steve Vai, Jake E. Lee, Warren DeMartini and George Lynch. But Charvels weren’t exclusive to metal players. Fusion giant Allan Holdsworth played custom Charvels, and in the late Eighties Jeff Beck exclaimed, “These guitars made me want to start playing again!”

Charvels were built for speed, but they also had a sound all their own. “They never sounded like Fenders or Gibsons,” says Dweezil Zappa, who acquired his first two Charvels in 1982. “They always had their own sound and personality. The guitars were built with more dexterity in mind. It was easier to reach the top frets, and the vibrato systems were set up well.”

Credit for the company’s mainstream success is due to Grover Jackson, the man who is considered the mastermind and father of metal guitars. Though he’s known today for the brand that bears his own name, Jackson first made his mark with Charvel after he bought out Wayne’s interest in the company in November 1978. Jackson and his team of noted luthiers refined the instruments and instituted production facilities that allowed him to bring Charvels to the masses.

Under Jackson’s guidance, Charvel grew in popularity throughout the Eighties as the shred phenomenon took off. Production began to shift to Japan in 1986, and in 1989 Jackson sold his interest in the company to the Fort Worth, Texas investment firm, International Music Corporation (IMC). Charvel’s numerous original employees went to work as master builders at Fender, where many of them still work today. High-quality Charvels continued to be manufactured in Japan, but the rise of grunge in the early Nineties reduced demand for the instruments. As the decade went on and sales waned, quality began to dip, and the brand became associated with inferior budget instruments.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

By the time Fender acquired Charvel in the fall of 2002, the brand had been all but abandoned. Over the past seven years, Fender has managed to return it to its old glory, thanks in great part to those many original employees in Fender’s ranks. Charvel senior product manager Michael McGregor says, “Charvel is a brand steeped in history and tradition. Building these guitars again with the original recipe is a true labor of love.”

Charvel’s colorful story is a convoluted history of genius, serendipity, iconic players, third-party financiers and talented builders. But whatever the circumstances, there was something special about each Charvel, whether it was made in America or Japan.

Grover Jackson says, “There was a vibe and a team spirit at Charvel that I never experienced anywhere else. Sometimes the good intention of the creator gets into the product, against all odds, and this was certainly true of every Charvel that went out the door.”

Charvel’s Guitar Repair

The man whose name is on Charvel guitars was a part of the company for only four years, but Wayne Charvel’s contributions and importance to the history of player-centric guitars can’t be understated. He was a typical Southern Californian hot-rod enthusiast, whose innate mechanical and artistic talents inspired his desire to help players improve and personalize their instruments.

Originally a sign painter, Charvel discovered he had a remarkable aptitude for guitar refinishing. In the late Sixties and early Seventies, he began to perform custom work for Fender, including paint jobs and pickup installations. Using other company’s parts, he also created two blonde Tele-style guitars for Billy Gibbons, a black Strat-style guitar for Ritchie Blackmore and a one-of-a-kind Plexiglas bass for the Who’s John Entwistle. Painting flames on guitars, as he did on several of Gibbons’ Fenders, became one of Wayne’s particular specialties. Charvel says, “As far as I know, I was the first person to ever paint hot-rod flames on a guitar.” Over the years, attention-getting paint jobs would be a defining characteristic of the guitars that bear his name.

Wayne opened Charvel’s Guitar Repair in 1974 in the Southern California town of Azusa. There, he continued to take on work from Fender, sell aftermarket parts and offer some custom services to the public. One noteworthy player who wandered into Charvel’s shop in the early Seventies was a young hotshot named Eddie Van Halen.

“Eddie came by the shop a lot and sometimes would sit on the floor and play the guitar while we repaired some of his other guitars,” Charvel recalls. “One day, Eddie came over to the shop and asked if I had an extra body and neck. I told him that I had an extra Boogie Body neck and an old body in my shop. I gave Ed the parts, and the next time I saw the guitar he had used a spray can to paint it white with black stripes. He used nails to hold the pickup in the body.”

This was the first of Eddie’s fabled “Frankenstein” guitars, as was featured prominently on Van Halen, the self-titled debut from Ed’s group. It eventually served as the template for the Grover Jackson–built black-and-yellow-striped Charvel superstrat that Ed can be seen holding on Van Halen II. Though Wayne couldn’t have imagined it at the time, his shop’s association with the guitarist would springboard Charvel’s success within a few years.

Although Wayne was well known for his paintwork, Charvel’s repair guru, Karl Sandoval was the shop’s main attraction. Sandoval is best known today as the innovator of Randy Rhoads’ polka dot V, but long before he worked on that guitar he was Charvel’s chief employee. Sandoval, who routinely worked on Van Halen’s guitars, introduced Eddie to Charvel’s shop and turned him on to using a Variac voltage-regulating device with his amps, something that Eddie has long credited with helping him create his signature “brown sound.”

After a year in Azusa, Wayne moved the shop to San Dimas, which is now widely celebrated as the birthplace of shredder guitars. Even though the shop offered repair services, most of Charvel’s business was from mail-order sales of Boogie Body and Schecter Guitar Research bodies and necks, pickups from DiMarzio (then in its first years as a supplier of aftermarket guitar pickups), and replacement parts. Many guitars of the time came stock with plastic and low-quality steel parts, and Charvel was among the first suppliers to offer superior replacement hardware, including brass bridges, stainless-steel tremolo arms and aluminum jack plates.

Unfortunately, parts and repairs didn’t bring in much money, so Charvel tried to expand into building guitars. For funding, he teamed up with an investment firm called International Sales Associate. Not much happened, however. By 1977, Charvel still wasn’t building its own guitars and was facing severe financial problems. In the early months of that year, an Anvil Case employee named Grover Jackson came into the shop to purchase a Telecaster body. A skilled guitarist, Jackson had been trained in guitar building by an Atlanta luthier named Jay Rhyne. However, it was his business skills that interested Charvel. The two men got to talking, and over lunch that day they decided to work together. In exchange for helping to turn around the company, Jackson would receive a 10 percent share of Charvel’s Guitar Repair.

Over the next year, the new partners worked together but disagreed vehemently about how to move the company ahead and begin building guitars in-house. In November 1978, after months of growing frustration, Charvel decided to sell the business to Grover for a total sum of about $40,000, which included Charvel’s debt load of nearly $33,500.

Grover Jackson Takes Over

On November 10, 1978, Grover took sole ownership of Charvel, with the monumental task of turning a faltering repair shop into a thriving guitar production facility. To begin paying off the company’s debt, Jackson borrowed $7,500 from his parents. He recalls, “My father said, if you piss this away, don’t come home again!”

Time was of the essence, and not only for financial reasons. The guitar world was finally becoming aware of Charvel: one of the first guitars built under Grover’s leadership was Van Halen’s yellow-striped, black Charvel superstrat. Van Halen’s first album had just been released, and guitarists were eager to get their hands on a guitar just like Eddie Van Halen played. Suddenly, everybody wanted a Charvel.

Unfortunately, Grover had no means to mass produce the instruments and get them to market. So he began to assemble a team of gifted young guitarists who were willing to learn the trade, some of whom had backgrounds similar to Grover’s, in furniture building and woodworking. A young guitarist named Mike Eldred was Grover’s first hire. He had initially and serendipitously come into the shop to commission a superstrat like the one his friend Eddie Van Halen showed him weeks earlier. Soon to follow were Tim Wilson, Mike Shannon, Todd Krause, Pat McGarry, Steve Stern, Mark Gellart, Pablo Santana and Kenny McCutchin, many of whom continue to work with Fender or Jackson today. This became Jackson’s dream team, and with it, he paved a future for Charvel.

While Charvel and his employees had built a few guitars, they had generally done so using parts from other manufacturers. That would quickly change under Jackson’s leadership. Grover recalls, “We had started making bodies for Mighty Mite and DiMarzio to stay afloat, but we didn’t know how to make necks yet.” With interest in Charvel guitars soaring, they had to learn fast. Says Jackson, “It was eight to 12 months before Charvels actually started rolling off the line.”

Charvel guitars debuted in Atlanta at the 1979 summer NAMM show. The relationships that Jackson formed at Anvil Cases helped him sell the first guitars to a handful of dealers, including Musician’s Supply, which became Musician’s Friend. Guitar Center in Hollywood, a hot spot for up-and-coming stars, soon became another major retailer for Charvel.

In preparation for the expected demand, the company quickly moved its operations from San Dimas to a larger facility in Glendora. Many players think that U.S.-built Charvels were made in San Dimas because they all had a neck plate bearing the company’s San Dimas P.O. Box number and address. In fact, almost every American-made Charvel built after Jackson bought the company came out of Glendora. He simply continued to put San Dimas neck plates on Charvels because the company’s San Dimas P.O. Box was close to his home and spoke to the company’s roots.

The new Charvel models received an enthusiastic reception from dealers and players. The company’s humbucker- and tremolo-equipped superstrat quickly became the favorite model and is still one of the most sought-after guitars on the used market. But Charvel also built an equally impressive San Dimas Tele and Explorer, as well as a guitar inspired by Eddie Van Halen’s modified Ibanez Destroyer, called the San Dimas Star. Mike Shannon says, “We all worked for perfection and quality—shaping necks to be fast and comfortable, doing superb paint work, and meticulously dressing the frets… Each guitar had a personality for the player to discover.”

One of the superstrats’ key features was a compound radius fingerboard. Eldred describes the flattening arc of the radius as being “like an inverted ice cream cone,” where the lower frets have a smaller radius that’s comfortable for chording and the higher frets have a flatter or wider radius that facilitates speed, low action, high bends, hammer-ons and arpeggios. Tim Wilson did the math to determine the measurements that made consistent production of a compound radius fretboard possible for the first time.

Early Charvel bodies were all made from heavy woods, typically ash. Lightweight woods didn’t become popular until Allan Holdsworth requested custom-built basswood Charvels. (A friend of Jackson’s, Holdsworth held rehearsals for his 1982 album, I.O.U., at the Glendora shop.) This was the first time that a lightweight wood was ever used by a major manufacturer on a solidbody electric guitar.

Another component featured on almost all Charvels was a modern tremolo from either Kahler or Floyd Rose. Most of the very early Charvels were built with Kahler brass vintage-style trems that were non-locking. A short time later, Charvel started mounting the double-locking Floyd Rose system that’s preferred by the majority of whammy and dive-bomb specialists. Steve Vai was an early fan of the whammy-equipped Charvels. He says, “Before I created my signature Jem model for Ibanez in the early Eighties, Grover Jackson was working on innovative guitar designs. He was one of the first to put a humbucker and a whammy on a body that actually worked. This helped shape much of the early Eighties dive-bombing extravaganzas that pervaded the metal guitar scene.”

Like Van Halen’s striped Charvels, Vai’s “Green Meanie” Charvel became a highly visible example of the company’s work and growing influence, making appearances on Vai’s Flex-Able album cover, numerous magazines and, later, in the video for David Lee Roth’s “Yankee Rose.” The guitar that became the Green Meanie was originally one of Grover’s personal superstrats. Vai borrowed the guitar to take on tour with Alcatrazz. A few months into the tour, he called Jackson and said that he didn’t want to part with the guitar and had painted it green. Jackson let him keep it.

While many players, including Vai, were content with an outlandish paint scheme on their Charvel, Randy Rhoads was not. He recognized the playability of a Charvel but wanted a guitar that had a more radical look, right down to the body shape. In December 1980, while in California on a break from the Blizzard of Ozz tour, Rhoads sat down with Jackson and began designing a new guitar. The result was an offset-bodied white V-style instrument that they named “the Concorde.” The appellation was later changed to RR1, for “Randy Rhoads Model One.” It remains one of Jackson’s most popular guitars.

The guitar’s look was very unusual for the time, however, and Jackson, fearful of alienating customers, was hesitant to place the Charvel name on the instrument. Instead, he put his own name on the pointed headstock, and Jackson Guitars was born. Jackson had made one V-shaped neck-through-body guitar for Swiss virtuoso Vic Vergeat that predated the Concorde, but Rhoads’ guitar was the first to display the Jackson logo. Going forward, Jackson became the sleekly insane brother to the wild, yet traditional, Charvel brand. From a construction standpoint, Jacksons were the company’s neck-through-body guitars and Charvels their bolt-on instruments. Ironically, considering Grover’s original concerns about the RR1, the popularity of Jackson’s aggressive styling soon overshadowed the more conventional-looking Charvels. By the mid Eighties, MTV looked like a 24-hour advertisement for Jackson.

Of course, custom and sometimes wild paint jobs remained a highlight of the Charvel/Jackson guitar lines. Numerous graphic artists worked to bring customers’ visions to life on Charvel and Jackson guitars, the first of which was Ernie Predrigon. Probably the best known and currently active of them were Dan Lawrence and Glen Matejzel. These artists painted everything from hot-rod flames, zebra stripes, snake skins and lightning bolts to skulls and blood, camouflage, and artist-specific paintwork. Lawrence says, “After Eddie’s stripes and Randy’s polka dots, graphics became the most popular way for someone to truly personalize the instrument.” Adds Matejzel, “Fans sometimes didn’t know a player’s name, but immediately associated a certain graphic with a band.” Among the most recognizable and requested paint jobs were George Lynch’s Bengal Tiger stripe and Warren DeMartini’s Japanese-themed Rising Sun graphics.

Even with the great demand for Charvels and Jacksons during the early and mid Eighties, the company was barely in the black. Jackson says, “I didn’t understand money. I was just thinking about product. I wanted to push the envelope. If I could do something better, I threw every nickel at it. There wasn’t enough margin built into the price, and we just weren’t turning a profit.”

In an effort to save the company and expand operations and distribution, Grover merged with International Music Corporation, a multi-product distribution and investment company based in Fort Worth, Texas. In return for giving up sole ownership of Charvel/Jackson, he received a 12 percent share of the larger company. Like many outside investors, IMC was primarily interested in shaking every dollar out of the company’s potential profitability.

The first change was to move all standard Charvel production to Japan, while Jacksons and custom Charvels continued to be made in Glendora. The newly funded company launched eight new Japanese Charvels, simply denoted as a Model 1, Model 2, and so on. By far, the most popular of these were the Model 4 and Model 6: the Model 4 was a bolt-on guitar with a humbucker and dual singlecoil pickups and a Floyd Rose–licensed tremolo; the Model 6 was a set-neck version of the Model 4, making it, essentially, a Japanese-built Jackson Soloist. Both models featured Jackson’s own active pickup system, an onboard gain-boosting preamp and a bound rosewood fretboard with shark-fin inlays. By any standards, they were exceptional guitars for the money and set the early standard for overseas guitar production. The neckplates on the Japanese Charvels replaced the San Dimas address with “Fort Worth, TX” a nod to the location of IMC’s headquarters. That soon changed. In 1986, in an effort to cut costs further, IMC moved Jackson production from Glendora to a facility in Ontario. With Charvel production situated in Japan, the Ontario facility was to produce Jacksons exclusively, although it did produce a few Charvels to satisfy a backlog of custom-ordered instruments.

The following year, as sales boomed, the Ontario facility reached its peak size with 135 employees, 28 of whom worked around the clock winding pickups, thereby making Charvel/Jackson the world’s largest pickup manufacturer—even if it was just making pickups for its own guitars. Both brands continued to sell extremely well for as long as metal ruled the airwaves. However, IMC wanted to lower costs further, and in 1989 the company decided to fire 80 percent of the Ontario staff and move the bulk of Jackson production to Japan. Grover unceremoniously sold his interest in the company and grudgingly moved on to other ventures. In doing so, he lost the right to use his name on a guitar, just as Wayne Charvel had 10 years before when he sold Charvel to Jackson.

Charvel After Grover Jackson

Charvel continued forward after Grover’s resignation, but the popularity of guitar music was waning in the growing shadow of grunge. Musicians revered for their virtuosity just a few years before were now accused of overplaying the instrument and lacking “feel.” With Jackson production moving to Japan, the Ontario plant was becoming a ghost town. In 1990, Tim Wilson recalls, “we began to experience severe layoffs in Ontario. We went from 107 employees to about 35 by the end of the year.”

Wilson stayed on as plant manager in Ontario for the next 12 years, before eventually joining his friends and many of his former Charvel coworkers at Fender. During that time, Charvel introduced several new lines, including the Classic Series, Fusion Series and Contemporary Series, as well as the semihollow Surfcaster, which had lipstick pickups. Most of these guitars were sleeker than their mid-Eighties counterparts and more like Jacksons in their body and neck styles. The logo was also changed during these years from the original guitar-shaped lettering to a whimsical and poorly received cursive style script that became known as the “toothpaste logo.”

Things weren’t entirely quiet at the Ontario facility. In 1993, Charvel began manufacturing a limited run of American-made San Dimas Series guitars for a store in New York City. Thanks to their popularity, IMC allowed Charvel to start taking custom orders. Although production quality had remained high throughout the IMC years, it began to suffer in 1998, when IMC sold the brand to the Akai Musical Instrument Corporation, which was a part of the Chinese firm, Semitech Global. The company shifted the remaining production to Korea and India, in the process severely crippling Charvel’s quality, reputation and what was left of its diminished sales.

Charvel Today

In 2002, Fender purchased Charvel and Jackson from Akai and began a concerted effort to bring the guitar maker back to its original form. Marketing manager Mike McGregor says, “We are fortunate to have many of the original Charvel builders and employees with their hands on these instruments. We also had access to a plethora of original Charvel guitars and numerous dealers and collectors.”

Eddie Van Halen’s striped EVH Art Series guitars were the first instruments to come out of the newly reformed shop, located in Fender’s Corona, California facility. The company also made a limited release of EVH Frankenstein replicas from the Custom Shop. Next were a Warren DeMartini signature model, two San Dimas superstrats and a San Dimas Tele. Fender’s ownership makes it possible for these guitars to feature the Stratocaster headstock once again. In addition, the models sport an exact recreation of the San Dimas P.O. Box neckplate: although a Costco now sits on the space where the hallowed San Dimas shop once stood, Fender receives mail at the Charvel shop’s former San Dimas address. And considering that Wayne Charvel set off the custom shop revolution, it’s only appropriate that the new Charvel has its own Custom Shop. Adding to the authenticity of Charvel’s customs, Dan Lawrence and Glen Matejzel are again painting many of Charvel’s graphics.

In one respect, the Charvel story has come full circle: It was more than 35 years ago that Fender commissioned Wayne Charvel to do his first official custom work on a Stratocaster. In another respect, the timing is perfect for the reborn Charvel brand. Virtuoso guitar playing has been on the rebound for the past several years. And then there’s the nostalgia factor: a lot of those new players were inspired by guitarists who did their shredding in the Eighties on a Charvel. McGregor says, “I’m delighted that there is a whole new slew of shredders emerging, many of whom take direct inspiration from the Eighties players who invariably shredded on a Charvel.”