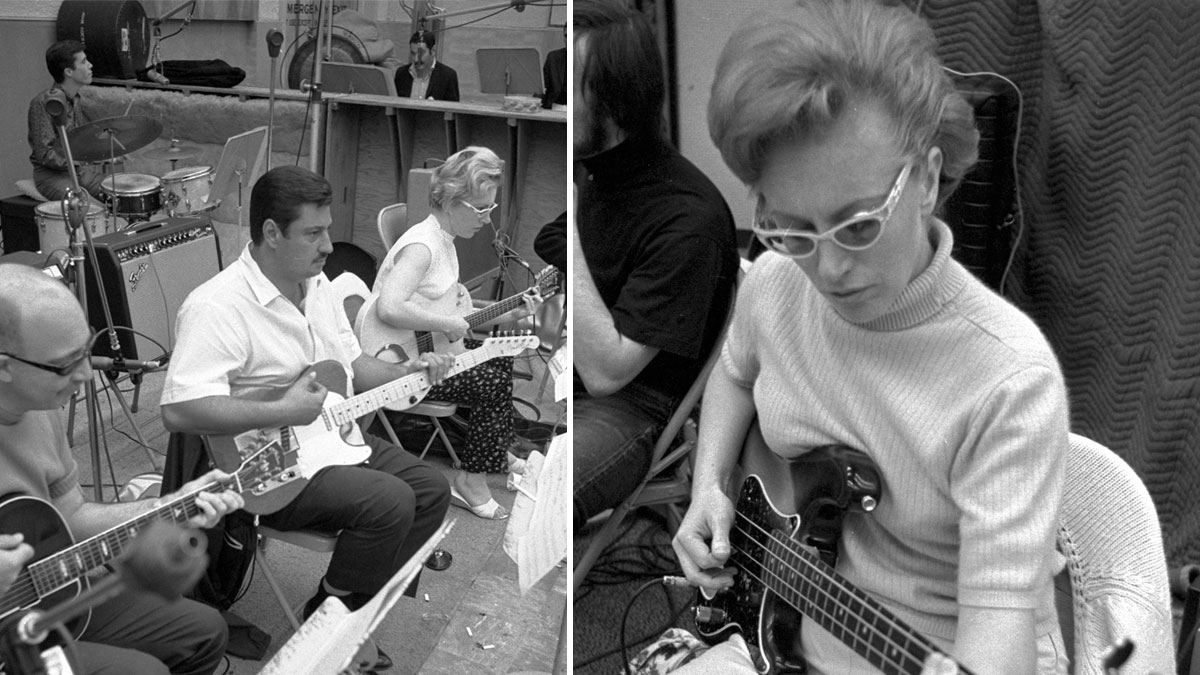

“I was in my sixth year as a studio guitarist when one day the bass player didn’t show up. The producer asked me...” How Carol Kaye became a session bass icon

If you’ve ever wondered what connects Frank Zappa to Frank Sinatra, Burt Bacharach to The Beach Boys, the answer is Carol Kaye. The session legend tells the story behind her career and legendary bass recordings

If plucking a ripe plum from a tree had a sound, it would resemble Carol Kaye’s signature tone – a tone that made her a ‘first-call’ bassist in the highly competitive studio session world. It wasn’t just that, though.

Kaye is arguably the first bassist to exploit the instrument in a truly melodic fashion, a nod perhaps to her early days as a jazz guitar prodigy. Her ability to invent memorable and influential bass and guitar parts on the spot in a high-pressure situation took her to – and kept her at – the very top of the studio scene and onto more than 10,000 recordings.

Carol Kaye was born into a musical family in Washington state on the Pacific Northwest in 1935, with both parents professional musicians. In 1942, they relocated to California and by the age of 13, she took possession of her first guitar. Incredibly, within a year she was proficient enough to take on students of her own alongside playing gigs in the local jazz clubs.

“I turned professional in 1948 after working with a fine jazz guitar teacher on the West Coast,” Carol says. “Within a few months I’d learned enough to be out playing jazz gigs. Almost everyone in those days had a musical instrument. If you think of how many people today have cell phones and computers, that’s how many people had instruments and how popular music was then. You heard real music everywhere: on the radio, TV and in the movies.”

The jazz scene

In the 1950s Carol worked for the jazz saxophonist Teddy Edwards. While in his band, she came to the attention of producer Robert ‘Bumps’ Blackwell who is best remembered for producing and co-writing with Little Richard on a string of rock ’n’ roll classics such as Tutti Frutti, Long Tall Sally and Good Golly, Miss Molly.

My Epiphone was Phil Spector’s favourite guitar sound; he loved that guitar

“I was asked by Bumps Blackwell to do some studio sessions for him,” Carol tells us. “I was working at the Beverly Cavern in LA at the time with Teddy Edwards and Bumps loved the way I soloed real jazz guitar. Everyone worked at the Cavern, but I played in dozens of jazz clubs with lots of different bands. I was one of the few, in late-’50s LA, that was esteemed for playing fine jazz guitar.

“In those days I played a secondhand Gibson ES-175 and a Gibson amp but traded it for an Epiphone Emperor. By the way, my Epiphone was Phil Spector’s favourite guitar sound; he loved that guitar. Around 1957 I swapped the Gibson amp for a Fender Super Reverb, which had an open back and four 10-inch speakers. I continued to use that amp even when I switched to bass in the early ’60s.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The song that Blackwell invited Carol to play on happened to be Sam Cooke’s classic version of the jazz standard Summertime. The track is underpinned by Kaye’s simple yet highly effective acoustic arpeggios on what sounds like her Emperor archtop. The A-side You Send Me went to No 1 on the American R&B chart and, later, into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame as one of the 500 ‘Most Important Songs’ list.

“From then on I decided to focus more on studio work,” says Carol. “It paid 10 times more than the jazz clubs paid and, by then, I had two children and a mother to support!”

Creating a feeling

In 1958 Carol played rhythm guitar on Ritchie Valen’s million-seller La Bamba at Gold Star Studios in Hollywood. Phil Spector, a regular client of Gold Star, noticed what Kaye was capable of and wasted no time hiring her for his own sessions. Ultimately, these sessions generated such ‘Wall Of Sound’ masterpieces as The Crystals’ Then He Kissed Me and You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’ by The Righteous Brothers, among many others.

Carol shares her experience of the sessions: “There was so much echo in the earphones on Lovin’ Feelin’ that no-one was playing well together. I had to bear down extra hard on my Epiphone, grinding away with rhythmic eighth notes, trying to congeal the rhythm together.

“Phil heard that and liked it so much he put a double-time echo on it, making it sound like I was playing 16th notes. It worked! We knew that was going to be a big hit. The tune was great and The Righteous Brothers were knocking our blocks off with the way they were singing. We’d never heard white singers sing like that before.”

Having to adapt to whatever the session might throw their way, these studio giants had to be able to sight-read sheet music as well as be top-drawer improvisers, well accustomed to adapting to those times when they’d merely be given a chord chart.

“Studio time was very expensive in those days. You’d have to record three or four tunes in three hours. We’d never heard the music before and had to be able to invent our lines and make sure the music sounded good. If you didn’t, you never got hired again. It was that simple!” Carol states. “The producers were there to make hit records and they booked the musicians that could deliver musically as well as be ultra professional on the record date.

Studio time was very expensive in those days. You’d have to record three or four tunes in three hours

“We would play several of these sessions every day! You drank a lot of coffee to stay awake, especially on those six-hour sessions where you’d have to first invent then record a whole album. Yes, it was boring a lot of the time, but you took care of business.

“There were no drugs or booze allowed in the studios. Anyone turning up drunk or high would never get another session. The drugs started to turn up in the ’70s and that’s when most of us quit the studio scene and started to concentrate more on movie work.”

From Tedesco to Burrell

The list of musicians who Carol worked with on sessions is intriguing. The vast majority were jazz players who’d grown up through the big-band era or were touring jazz clubs across the States before settling for the relative comfort of the studio scene. Joe Pass, Barney Kessel, Howard Roberts, Tommy Tedesco and Kenny Burrell were just some of the heavyweight guitarists Kaye regularly played with on studio dates.

“People don’t realise this fact: all of those ’60s pop records were played by jazz musicians! The guys on the album covers, bar the singers, didn’t record their own parts; we did them. We were the only ones who had the reading and improvising skills to handle the pressure of those sessions.

“It wasn’t until the ’70s that the rockers were good enough to play their own parts on record – and, even then, they couldn’t do it in the short time we did. By then, bands were taking months to make an album that used to take us a few hours.”

Carol’s list of credits through the ’60s and into the ’70s is a veritable who’s-who of top‑level recording artists of the day: Ike and Tina, The Beach Boys, Simon & Garfunkel, Sinatra, Sonny and Cher, Neil Young, The Monkees, to name just a few. By this time, Carol had switched to playing a Fender Precision Bass through her Super Reverb guitar amp.

I found that my Fender Precision strung with flat-wounds and played with a pick created the sound all the producers wanted

“I was in my sixth year as a studio guitarist when, one day in 1963, the bass player didn’t show up at a session. The producer asked me if I could play bass and I found it was a lot more fun to play and created good, interesting lines, [rather than] playing all those rinky-dink silly parts on guitar that we all had to dumb-down for on those rock and pop records.

“I found that my Fender Precision strung with flat-wounds and played with a pick created the sound all the producers wanted. I stuck a piece of foam on the bridge to stop those horrible overtones, which also produced a slightly muted effect that became really popular for hit records.

“Having been a jazz guitarist it was easy for me to invent basslines for those records. Us jazz musicians hated the bulk of the pop records we played on, but I liked some of it – [such as] the more creative stuff like The Beach Boys. Brian Wilson was the only pop composer that wrote basslines for me and they were very good, but the rest I had to make up on the spot.”

The male-dominated world of the ’60s studio scene could be intimidating for women but not for Carol Kaye, who quickly became known as the best bassist in the business. Quincy Jones wouldn’t do a session until Carol was available and Brian Wilson called her “the best bassist in the world and way ahead of her time”.

You know, a note doesn’t have sex attached to it. You either play it good or you don’t. Some people can’t handle that, especially men

Carol recalls: “There were always women who worked with men in the jazz groups and big bands going back to the 1920s, but there were very few women in the studios – just a few who played in string sections or on harp.

“You know, a note doesn’t have sex attached to it. You either play it good or you don’t. Some people can’t handle that, especially men. They want to see the bass as a masculine thing, but when you hear a bass played with balls… that’s me!”

Levelling the score

As the ’70s progressed, things began to change in the studios and many of the top session artists were leaving the scene. Carol continued to record for film composers such as Lalo Schifrin (Mission: Impossible) and Henry Mancini (Pink Panther) alongside laying down bass parts for TV shows such as M*A*S*H, Hawaii Five-0, Ironside, Kojak and, appropriately, Wonder Woman.

Carol released a series of guitar and bass tuition books to complement her growing teaching commitments and contributed to such movie scores as Bullitt, Planet Of The Apes and Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid.

You had one take to get your parts right on those movie sessions. The money people weren’t into wasting time repeating things you should’ve got right first time

“You had one take to get your parts right on those movie sessions,” says Carol. “The money people weren’t into wasting time repeating things you should’ve got right first time. It was no pressure, though. We knew what we were doing and we were thrilled to work with some of the greatest film composers of all time.

“Apart from movies and TV shows, I quit the studio scene and went back to playing jazz. I’d missed it so much. I’d been playing so much eighth- and 16th-note basslines that I’d started losing my jazz chops. I had all kinds of guitars for the studios: electric, acoustic six- and 12-strings, even mandolin, banjo and a Danelectro baritone guitar.

“You had them all in the trunk of your car along with your Fender amp with spares for all. I never had time to change my strings. Every two years I’d go to the store and buy a new bass and that would be my new strings! After all those years I was happy to be back playing jazz in the clubs and at festivals, writing my books and helping people with music, spreading the truth to hopefully get rid of all the ego-driven BS out there.”

Today people are fighting for credits, they’re fighting for ‘me, me, me!’ We didn’t think like that; we thought ‘us, us, us’

To have played on so many iconic record sessions without a name-check might irk many musicians these days, but Carol Kaye is quick to point out that the studio scene wasn’t like that then. The studio musicians played each session knowing they would not be credited for their work on any album sleeves and didn’t expect to be. All egos had to be left in the parking lot, and from the moment the tape started rolling, it was business as usual.

“Today people are fighting for credits, they’re fighting for ‘me, me, me!’ We didn’t think like that; we thought ‘us, us, us.’ As a group, we were just trying to create a product, we did our best to turn those things into hits and we had a lot of success with that attitude. Music is, after all, a business and if more musicians thought that way, we would have a damn good business.”

- Carol Kaye’s series of tutor books and her 502-page autobiography, Studio Musician, are available from CarolKaye.com.

Denny Ilett has been a professional guitarist, bandleader, teacher and writer for nearly 40 years. Specializing in Jazz and Blues, Denny has played all over the world with New Orleans artist Lillian Boutté. Also an experienced teacher, Denny regularly contributes to JTC and Guitarist magazine and is founder of the Electric Lady Big Band, a 16-piece ensemble playing new arrangements of the music of Jimi Hendrix. Denny has also worked with funk maestro Pee Wee Ellis and is the co-founder of Bristol Jazz & Blues festival.

“I was playing stuff I don’t think James Brown understood. He told me, ‘You have to play the one – you’re playing too much’”: Six years after he quit touring, Bootsy Collins reflects on James Brown and George Clinton, and what he gets out of playing today

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)