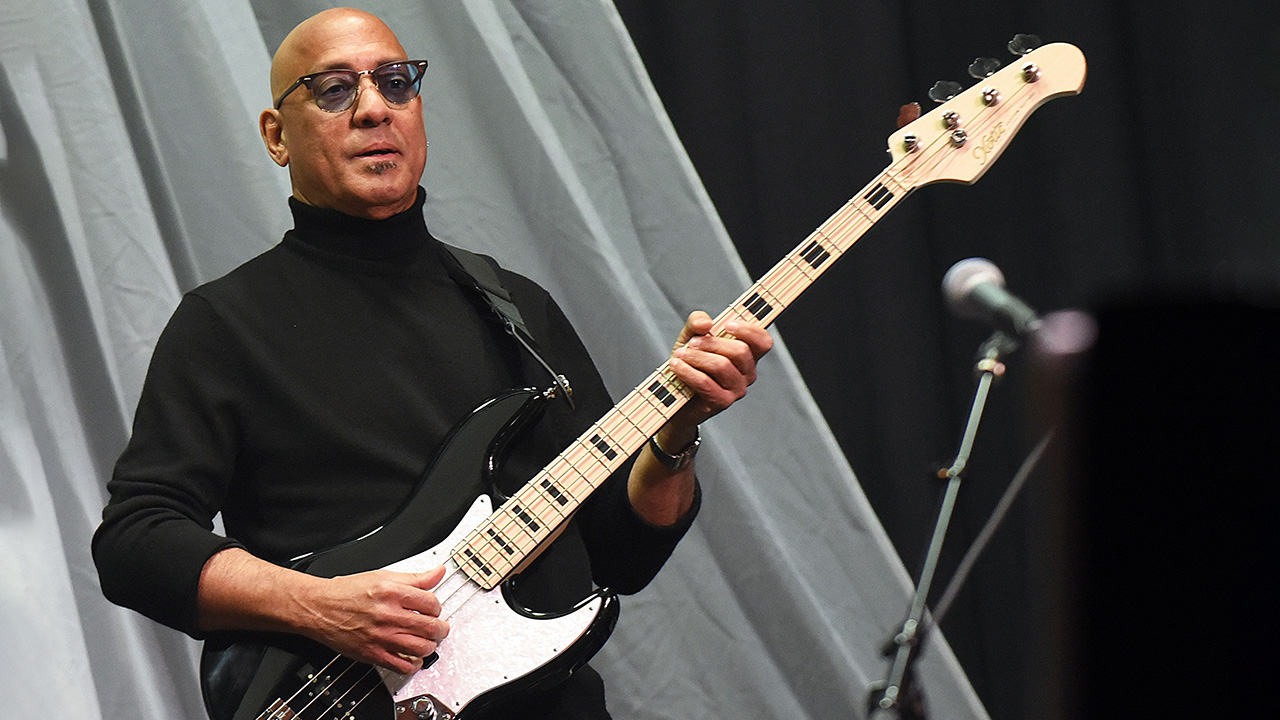

“I got a call from David Bowie’s people to record Let’s Dance. I became a big advocate of Stevie Ray Vaughan in the studio. Nobody else could play like him”: Session bass great Carmine Rojas shares the stories behind his awe-inspiring resume

Despite suspecting he used the wrong bass on Tina Turner’s Foreign Affair, the veteran dedicates himself to being a supporting player and learning every day with the likes of Keith Richards, Joe Bonamassa and Billy Gibbons

If you're looking for a bassist capable of injecting doses of R&B, rock, blues and more into your musical cocktail, look no further than Carmine Rojas.

Born in Brooklyn in 1953, Rojas came of age in the ‘60s as music exploded into a kaleidoscope of differing genres. He traveled to Europe to hone his bass chops before heading back Stateside to grab the gig of a lifetime with David Bowie, who was about to record landmark 1983 record Let’s Dance.

“By that point, I had learned that as a musician, you need to be ready – no matter what – for when the calls come in,” Rojas tells Bass Player. “Otherwise they'll call somebody else.”

Thankfully, Rojas was available, secured the gig without an audition, and was thrown into the studio alongside Stevie Ray Vaughan en route to one of David Bowie’s best albums.

“Criminal World is a great example of what I did there,” he says of his approach to the work. “At that time, I was all about blending English-based rock with American R&B. China Girl is another example of how I could experiment that way. I loved that David never repeated himself, which was an interesting experience.”

Rojas later lent a hand to Alphaville, Julien Lennon, Rod Stewart and Joe Bonamassa. He’s hung around with Richie Sambora, Keith Richards, and most recently, Billy Gibbons. But as glamourous as it sounds, he says life in music is often about survival.

“The big thing is staying fluid, and avoiding the superficial bullshit,” Rojas argues. “Sticking to who I am, staying true, and being at the right place at the right time has been my gospel.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I stay professional, be on time, do my homework and stay supportive. That’s what true greatness in music is all about. The other angular stuff you can mention has nothing to do with moving forward.

“Life will test your shit to see if you're strong enough. You must be tough to navigate it all. But more importantly, you must be sincere. Being that has probably saved my life.”

What inspired you to pick up the bass?

“I originally wanted to be a drummer, but that didn’t go well! So I gravitated toward bass because it sounded soothing – kind of like a warm blanket. I wasn’t too sure about it; I quit like three times. I got pushed back into it because a local R&B band needed help. But early on, I didn’t understand it; it wasn't until I stopped trying that it came to me organically.

Were you primarily self-taught, or did you take lessons?

“I’m 80 percent self-taught. Whenever I’d try to take lessons at school, I’d struggle because someone was watching me. It’s better to be in a spot where you have to play, and you’re able to learn what works for you. The more I played, the more I naturally understood bass guitar.”

How did you hook up with David Bowie in the early ‘80s? Was there an audition?

“In ’82 or ’83, David was looking for an organic-sounding band with Black and Puerto Rican musicians who had that Latin-sounding R&B vibe, but also did rock. Dating back to the ‘70s he liked having a bunch of urban guys who didn’t just play things straight.

“So I got a call from David’s people – but I didn’t know it was for David then – and I ended up being invited to the studio to record for Let’s Dance. There was no audition, and I kind of got what I needed to do. I had been a fan of Bowie since the ‘70s, so I knew he wanted musicians that would give him the freedom to do what he did.”

Do you remember being in the studio with Stevie Ray Vaughan?

“That was interesting because I’m a big Hendrix fan, and Stevie was like the best of both worlds. I remember Albert King being asked to do Let’s Dance, but he wasn’t available, and Keith Richards turned David onto Stevie.

“David always had interesting guys like Mick Ronson and Robert Fripp around, so it made sense to have a guy like Stevie who could add a twist. After meeting Stevie and hearing him play, I became a big advocate of Stevie in the studio. To me, he was the ultimate guy who pulled all that shit off, man. Nobody else could play like him.

“But it was weird for me because, at first, it was just Stevie and Omar Hakim on drums, and when it got to me, it was a skeleton. From there, I’d piece together the song and add my parts.”

I became a big advocate of Stevie Ray Vaughan in the studio. To me, he was the ultimate guy who pulled all that s**t off, man

What gear did you use on songs like Modern Love, China Girl and Let’s Dance?

“I ran my bass directly through an old Ampeg, which is what I used for the whole album. The bass had a Fender Jazz body, a Tele neck, one EMG pickup and one DiMarzio jazz-style pickup that I was experimenting with. And I played all the songs with a pick, even though it doesn't sound like it. But I had spent time in Europe, and that’s what many English bands were doing.”

After working with David Bowie, how did you end up in the studio with Tina Turner during the recording of Foreign Affair?

“Tony Joe White was working on that album as a writer and producer, and he wanted musicians who weren’t just typical New York players. He wanted guys who could do some organic swampy stuff, so I got the call. It was me, Eddie Martinez and other guys who grew up together in New York City.”

The Best was a huge hit. Do you remember recording it?

“I remember doing the demo for it, but when it came time for the actual recording of the finished song, they went with T.M. Stevens. For the demo, I used my Japanese-made Westone Spectrum bass – they were big back then. It was a five-string, and I believe I had a red and black one; I used both on Foreign Affair.”

Did the five-string Spectrum bass urge you to approach things differently than you had with your Bowie Frankenbass?

“The feel of it did – the feel of the wood, the way the neck was, and whether the strings were rounds or flat wounds all impacted things. The strings significantly changed the approach because they put me in a different place. It’s like picking up somebody else’s bass, which leads me to play differently.

“I also remember the neck configuration and some of the electronics being different from the Fender. The Spectrum doesn’t sound quite right on some of the tracks – maybe an analog bass would have been better.”

Later, you joined Joe Bonamassa’s band and stuck around for a long time. How did you get the gig?

“There was no audition for that, either! This time, it was another phone call from drummer Jason Bonham, asking if I was free. We both lived in L.A. and knew each other, and he knew I could handle it. It was cool to get back into blues again and work with someone like Joe, who was influenced by English players.

“It felt good right away. Joe was different because he took a British blues approach but didn’t just copy it – he was able to make up incredible stuff on the fly. He showed there can be more to it regarding motions and chord changes. Basic blues music is fantastic, but he ended up rearranging a lot of things and fucking killing it while doing it.

I’m a support player, and I always give support… When you have a guy who isn’t afraid, you can go anywhere, but he needs support

“When I got the call I was told, ‘There’s not much money involved in this project, but we feel you’d be great for it.’ They were right. Jason and I helped put Bonamassa on the map, and the tightness of that band landed him in a different space. He went from playing blues clubs to playing bigger theaters and halls. We ended up being perfect together.”

What’s the key to locking in with a guy like Joe Bonamassa?

“Stay out of his way! Joe grew up listening to Hendrix, Cream and Traffic, and I listened to those bands too, so I knew where he needed me to land. I’d maybe alter the bassline so it would always fall where he needed it, and it worked. If you watch us playing live, there was some jamming, but it mostly came down to me being supportive of what Joe was doing.”

Is that the key for you in most situations?

“For the most part, yes. I’m a support player, and I always give support. And with Joe, he wasn’t afraid of anything. When you have a guy who isn’t afraid, you can go anywhere, but he needs support. The more support I can give, the better off we’ll be when we’re going off to new places.

“But it was always organic – a matter of plugging in and listening to what the track needed. You must know what the movements are. If you're trying to play blues, you’ll fall flat. We made the blues come alive again, and much of that depended on that rhythm section backing Joe up.”

You’ve also played alongside Keith Richards during his solo shows at times.

“Keith Richards is the real deal. He’s 1,000 percent above everybody with how he goes about it, man. Keith is not there to impress, and he’s not in competition with anybody.

“I get along with him because I’m the same way as a bassist – I don’t compete with anybody. I just want to play bass, have fun and enjoy life. With Keith, it’s about being supportive, which is probably why we get along so well; he understands that mindset.”

What’s it like to jam with a guy like Keith Richards?

“It’s amazing! I remember being a kid and watching him on TV with the Rolling Stones, when Brian Jones was in the band. And then you had Mick Taylor and Ronnie Wood, but Keith was always the most interesting to watch.

The thing with Keith Richards is he loves music, and you see it when you’re with him. It’s in his body movements

“Getting to sit, hang out and play with him, be a part of the air that he takes up, man, it’s incredible. The thing with Keith is he loves music, and you see it when you’re with him.

“It’s in his body movements; he’s unbelievable. With Keith, there’s no lies and no bullshit; it’s nothing but the truth with Keith.”

Lately you’ve been playing alongside Billy Gibbons during his solo shows.

“We’re playing those great ZZ Top songs, a lot of which he doesn’t do when he plays with ZZ Top. I love playing with Billy because he’s an educator, and it’s different from other gigs. But I’m comfortable – it’s a matter of swimming in new waters and adapting.

“When you play with guys like Keith, Bonamassa or Billy, learning their background as musicians and what makes them tick is essential. Understanding what they like to listen to and gathering information so that you can share that with them and play it is everything.

“And Billy, like I said, is like going to school; he points me in directions for basslines based on how he hears things. It’s amazing.”

Where do you go from here?

“I still get calls to do the David Bowie alum stuff, and there’s more of that in New York City for 2024. But I’m wide open to new opportunities, and I want to be able to play music and be supportive.

“Like I said, I’m not in competition with anybody, and I still love doing what I do. I don’t take anything for granted; I’m very grateful and truthful about who I am – and it works. I’m still going to school, even though I’m 70. I’ve still got things to learn, and I’m still loving it.”

- Follow Carmine Rojas on Instagram for updates.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

“I asked him to get me four bass strings because I only had a $29 guitar from Sears”: Bootsy Collins is one of the all-time bass greats, but he started out on guitar. Here’s the sole reason why he switched

“I got that bass for $50 off this coke dealer. I don’t know what Jaco did to it, but he totally messed up the insides!” How Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan went from buying a Jaco Pastorius bass on the street to fronting one of hardcore’s most influential bands

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)