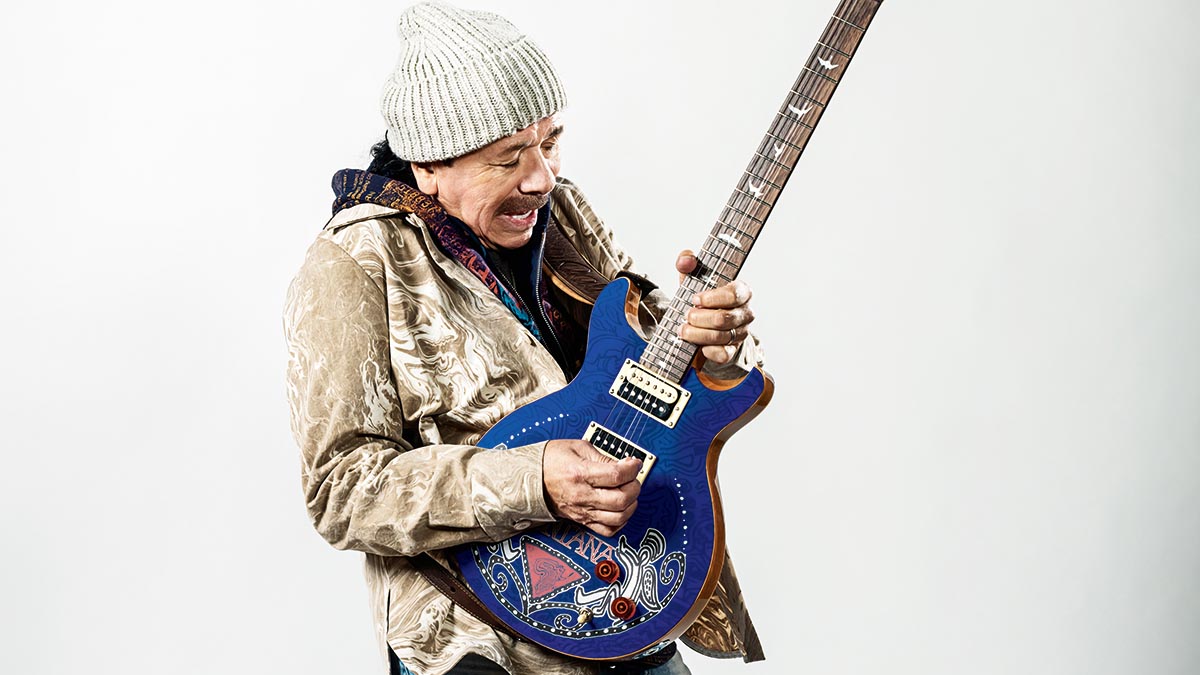

Carlos Santana: “When I play guitar, I’m a kid with a first-class ticket to Disneyland, and I can go on any ride I want”

As the guitar god returns with a new all-star collaboration album, Blessings and Miracles, he joins us to talk Strats, snakes, improv and acid…

As an interviewee, Carlos Santana operates on a higher plane. Not for him the oily talk of truss rods and trim pots, nor analysis of such earthly tangibles as scales and modes.

For the famously spiritual Mexican guitar god, music is a thunderbolt from the cosmos, the guitar a magical lightning rod, and his fingers the emissaries of some higher power.

He can’t explain how he does it, other than via some of the most extravagant metaphors ever uttered by a rock star. “Every day, when I play guitar,” he muses, “I’m a kid with a first-class ticket to Disneyland, and I can go on any ride I want.”

As one of the star turns at 1969’s Woodstock festival, Santana is a glorious product of those peace-and-love times. But that’s not to say the 74 year old hasn’t moved with them.

Following three decades of genre-busting, jazz-tinged output, Santana exploded into the mainstream with 1999’s all-star Supernatural album, and this year’s Blessings and Miracles is a sequel of sorts, corralling everyone from Kirk Hammett to Steve Winwood. “What message do I want to spread with this album?” ponders Santana. “Hope and courage.”

Are you pleased with Blessings and Miracles?

“Yes, I’m very grateful. It was divine intelligence that orchestrated all of these wonderful artists, writers and musicians to align themselves to be part of my life. It’s pretty crazy because about 60 per cent of them, I have yet to meet in person. We did a lot of it by Zoom. But once you close your eyes and use your imagination, they’re right next to you anyway.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What emotions do you feel when you walk into the studio to play guitar?

“It’s stimulating. Intoxicating. Inspiring. Elevating. I don’t find it a challenge any more. It’s very natural to trust in the unpredictable and know that what you’re bringing to the song will complement it.”

Do you use a framework or fly by the seat of your pants?

“Yeah, by the seat of my pants. Miles Davis used to say, ‘Play like you don’t know how to play.’ Purity and innocence are the best components for any kind of music.”

The guitar instrumental Santana Celebration is like an explosion. What emotions were going through you while recording that?

“Woodstock, Tito Puente, BB King… I feel all of them on that track. A track like that, you just have to do it on the spot. Say your piece. I feel it is important to tell my mind to shut up. Because the mind always wants to criticise and analyse everything.

“I don’t want to give my mind any room for disturbing what I’m doing. When you create a CD like Abraxas [1970], Supernatural [1999] or Blessings and Miracles, literally, it’s like giving birth to a baby. And you don’t want your mind to disturb the baby. So you tell it to get the hell out of the room.”

It takes balls to improvise like that, doesn’t it?

“Well, take someone like John McLaughlin, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker. Look at the way they improvise. It makes you feel like you should venture into discovering something you also have in you: the language of light that can bring clarity to darkness. You have to trust that your fingers will know what to do, where to do it, how to do it, with how much feeling, passion and emotion.”

How about your guitar work on the first single, Move, with Matchbox Twenty’s Rob Thomas?

“I felt like a child going on a waterslide. Some people get in trouble because they have a mother who doesn’t like to clean the floor after you splash water out of the bath. To me, it’s like, I keep splashing – and it’s okay. Rob trusts me. I trust him. We’re like surfers, waiting for the seventh wave.”

Do you think about things like scales and modes?

“No, I left all that in junior high school. A friend of mine, he says, ‘Some people use pentatonics. Some people use hair tonic. I drink gin and tonic…’”

What are your memories of recording America For Sale with Kirk Hammett?

“That one, we did play in the same room. Kirk was stood right next to me, and I said the same thing to him that I said to Eric Clapton once: ‘Look, man, we don’t need to do the duelling banjos thing. Why don’t we just have a nice conversation?’ Kirk has a vast vocabulary as a guitar player and gunslinger. And he’s in the most important band in the world.”

What’s the secret to collaborating successfully with another guitarist?

“I utilise fear as fuel. Not to scare me but to dare me.”

Did Kirk bring along the Greeny Les Paul?

“Yes, he did – and he let me touch it. It was like the first day I ever touched it. Because when Peter Green was getting ready to leave Fleetwood Mac, he would catch a plane, show up at a Santana concert, hang out with us – and I would invite him to play. So he let me touch Greeny then, too. And it was like, ‘Whoa.’ It’s like the Holy Grail, or Merlin’s magic wand.”

Did it hit you hard when we lost Peter?

“Yes. He was my brother, my friend. I played Peter Green every night when I played Black Magic Woman. I remember the first time I ever played that song, in a Frisco parking lot, when we were doing a soundcheck. I said to myself, ‘Okay, this is Peter Green’s song, but I have to reach out to Wes Montgomery and Otis Rush, and play that.’”

What guitars did you use to record Blessings and Miracles?

“I used my gold Paul Reed [Smith] single-cut [gold-leaf Private Stock model]. Under any weather or any condition, that guitar delivers whatever is needed. I don’t know what pickups I’ve got in there; I’ll have to ask Paul Reed. All I know is that they sound really good.

“This is the first album that I did not use Mesa/Boogie amplifiers on. We have parted ways. I used Dumble amplifiers, the 100-watt Overdrive Reverb. Dumble is the sound of flesh against flesh. I also used the Bludotone 100-watt Universal Tone: it’s an amplifier that’s made in Colorado. I try a lot of different things, but I always go back to just my fingers, a Cry Baby wah-wah and the amplifier.”

How has the design of your PRS signature evolved since the 90s?

“Paul Reed is very committed, like I am, to expand and grow and glow. Y’know, don’t be stuck with just one thing. I love that he has a pursuit for developing the way the guitar looks but especially the way it sounds. So he’s working with pickups to make it sing, like a violin with the longest bow. It’s a natural development. The guitar evolves like a spirit. I am always looking for a guitar tone that sounds bigger than life.”

The SE models have been successful, too…

“It took me almost 20 years to convince him to make student models. The guitars that I play – young people in high school, they can’t afford them, unless they have rich parents. And they have become a very profitable and lucrative endeavour.

“I take the student models on the road. Because I don’t want to take the crème de la crème. They have earned the right to stay in a special place, here in our vault. So I take a student model because they’re very reliable. They stay in tune and they sound great.”

Do you think you could you make a $100 guitar sound like you?

“Absolutely. I can make any guitar sound like me.”

Have you found you’ve ever been tempted by other guitars?

“For five or seven years, I played a Strat a lot – not so much on stage but in the studio. I recorded three or four albums just with a Stratocaster. That was the last 10 years, until this album, which is purely Paul Reed, in the studio and on stage. But before that, I was using this funky old Strat I found in Chicago. A really beat-up one. I wanted to get a gnarly, scratchy, cheap-guitar sound. But I’m done with that.”

What’s happened to your old SG?

“I’m sorry to tell you I threw it against a brick wall and it became a bunch of toothpicks. Because it wouldn’t stay in tune. That’s why, at Woodstock, I said that I was wrestling a snake – because the SG wouldn’t stay in tune.”

You once said rock ’n’ roll is a swimming pool, jazz is an ocean and you hang out on a lake: is that still how you view it?

“Pretty much, yes. An ocean is Charlie Parker, Coltrane, Miles, Wayne Shorter and John McLaughlin. It’s a different form of supreme improvisation.”

And do you feel like you can you drop into that world quite naturally?

“Y’know, what comes more naturally to me is making a melody come true.”

Could you ever go in the other direction – play with a punk band, say?

“Oh, yes. Absolutely. I would love to do an album that’s just heavy metal. Because I love AC/DC, Metallica, Led Zeppelin, Cream, Jimi Hendrix. The original Fleetwood Mac, with The Green Manalishi and Oh Well – that was heavy metal before heavy metal.”

Do you ever worry we’ll eventually run out of original guitar parts?

“No, I don’t – because it’s a language that will always develop, like living water. I think it was Tony Bennett that said, ‘If you take from one person, it’s called stealing. But if you take from many, it’s called research.’”

Do you feel your influence on the guitar scene?

“I was kind of curious, so I looked, and there’s, like, 70 Santana tribute bands, all over the world. There’s people who make their living playing Santana music. I’ve watched them, here and there.”

What advice would you give a Santana tribute band?

“I would just say, ‘You were born with your own fingerprints. You were born with your own sound, uniqueness, authenticity, individuality. I’m grateful and it’s a compliment that you play my music. But I would invite you to find your own because you’re going to be happiest when you create music that is totally you, by you.’”

Which guitarists are you listening to lately?

“What really excites me lately is Sonny Sharrock. I love how he became a living hurricane and tornado. He can play a melody, but you know that he’s just going to burn, on a whole other level that’s between Jimi Hendrix and Coltrane. I love Gábor Szabó – he was a Gypsy guitar player from Budapest.

“At home, I put on my guitar and I take my fingers for a walk with Gábor Szabó. I play a lot of Marvin Gaye, too. Why? Because they’re really sexy guys. Their whole thing is romance and S.E.X. And I need that in my life. I need to have romance and sex to keep me feeling young and vibrant.”

Do you think guitarists can keep evolving – or do you think you reach a certain point where you’re as good as you’ll ever be?

“They’re both one. You’ll be as good as you’ll ever be every time you get out of the way and let your spirit play. But there’s always room for more Mona Lisas, more Picassos, more Stravinskys. There’s always room to discover the unknown and unpredictable.”

When I close my eyes and I play, I always think of The Doors, which is one of my favourite bands. I love The Doors more than anyone or anything

Are there any guitar techniques you’d still like to perfect?

“I don’t want to perfect a technique. I’d rather develop innocence and purity.”

Do you think the music and messages of the 60s still resonate today?

“Yes. When I close my eyes and I play, I always think of The Doors, which is one of my favourite bands. I love The Doors more than anyone or anything. There’s something about The Doors and Light My Fire and Robbie Krieger… I guess he was listening to Ali Akbar Khan and also Ravi Shankar. But The Doors is the ultimate garage band.”

Does music still have the power to make the world a better place?

“Yes, absolutely. If they played more music by The Doors or John Coltrane in elevators, shopping malls, radio. Music reminds people that we are divine. No matter what your mind says or what the media says. A ‘media mind’ is not necessarily good for you. Sometimes you turn off the TV and you can hear the clouds moving, the birds chirping, children laughing.”

When you listen back to 1969’s self-titled debut album, can you recognise yourself as a player?

“The last time I saw my friend Joe Cocker, I said to him, ‘Hey Joe! We used to be charcoal and now we’re diamonds.’ He looked at me – he was putting on his pants – and he goes, ‘Did you just come up with that?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ I love Joe Cocker, and I love what we did with Little Wing. But anyway, he agreed, and when I listen to that music from ’68 or ’69, it’s kind of like charcoal, but it has become more like diamonds now.”

It was funny to be, one minute, in high school and then, next minute, we’re in the studio, and then we’re hanging around Miles and Herbie, and then it’s Woodstock and Jimi Hendrix

Do you have any favourite memories of that debut album?

“It was funny to be, one minute, in high school and then, next minute, we’re in the studio, and then we’re hanging around Miles and Herbie, and then it’s Woodstock and Jimi Hendrix. It was a little daunting to go from washing dishes and dreaming you could be onstage with BB King and Peter Frampton. And then – you are!”

You partnered with John McLaughlin on 1973’s Love Devotion Surrender. Would you ever consider working with him again?

“Yes. We were talking about it. I think we made a lot of people angry with that album. Which is a good thing. When you make someone angry, at least they’re paying attention. They all jumped onboard 20 or 30 years later, but when they first heard that album, it was like, ‘How dare you?’ And I was like, ‘That’s a good word. Because we dare.’”

Why do you think there was criticism of that album?

“Because people who are intellectually living in their minds, they couldn’t conceive of John McLaughlin and I desecrating John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. But I knew it was great because the one person that meant the most was Alice Coltrane – and she loved it.”

How have you coped mentally with the lockdown?

“I was doing time in paradise. Some people do time in San Quentin or some kind of correctional institution. I was in Kauai. So my lifestyle was rainbows and waterfalls. Beauty and grace. And being with my wife, Cindy, we’ve learned to crystallise our intentions, motives and purpose, and we have become better human beings. More spiritual, powerful warriors.”

Did you find yourself reaching for the guitar during lockdown?

“I put it away – knowing that any time I grabbed it, I could still find the G spot.”

Were you worried about catching Covid?

“No. I don’t think about it. I did take the shot, the injection. But I don’t succumb to fear and worry. I trust that when the time comes for me to transcend into another realm, I will. But right now, I got some things to do, so Coronavirus, fear and worry – I dismiss them.”

Finally, would you ever take LSD again to see how it affects your guitar playing?

“You got some…?”

- Blessings and Miracles is out now via BMG.

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.

“There’d been three-minute solos, which were just ridiculous – and knackering to play live!” Stoner-doom merchants Sergeant Thunderhoof may have toned down the self-indulgence, but their 10-minute epics still get medieval on your eardrums

“There’s a slight latency in there. You can’t be super-accurate”: Yngwie Malmsteen names the guitar picks that don’t work for shred

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)