Carlos Santana: "You'll get scratched once in a while when you jam with other people. But that's all part of it. You have to be bold"

In this 1988 GW interview, Santana opines on the power of the blues, his collaborations with John Lee Hooker, Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter, and the high-wire magic of jamming

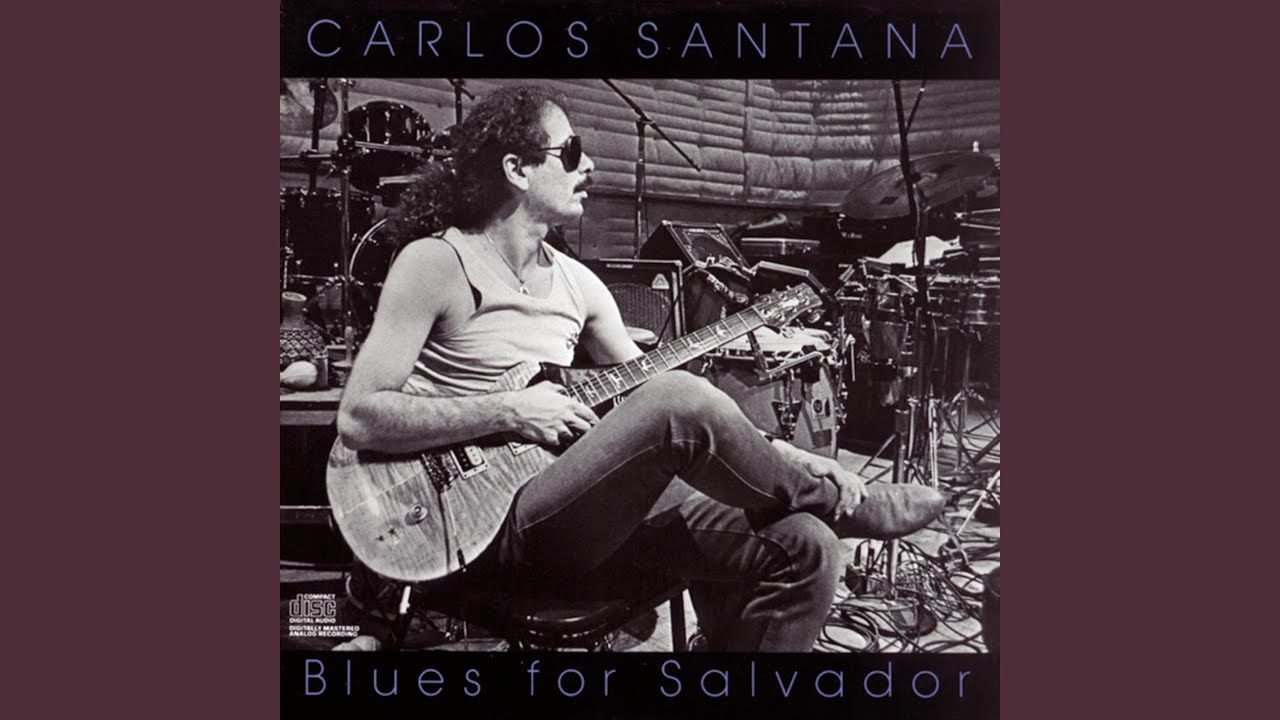

Here's our interview with Carlos Santana from the June 1988 issue of Guitar World, which featured Yngwie Malmsteen on the cover. The original story, which started on page 18, ran with the headline, "Another Kind of Blue: Carlos Santana has embarked on yet another musical adventure, one that has a lot to do with theory, and everything to do with the guitar."

He’s sitting on the bed of his hotel suite, playing his Paul Reed Smith guitar, staring out the window on a rainy day in New York and thinking about where his new direction might take him.

“I know I’m not the kind of person who’s gonna wind up a walking jukebox, like many rock ‘n’ roll artists,” says Carlos Santana. “They just play their hits and that’s it. That doesn’t appeal to me. I don’t wanna just go out and play Black Magic Woman and Oye Como Va all night because that was part of the Seventies, and my watch says it’s 1988. So I wanna get into ’88 and not look back.”

A little over a year ago, I chided Carlos in a Guitar World record review of Freedom. "Scrap the sappy, safe, predictable, slick pop arrangements and get back to playing the guitar, man," is what I said, or words to that effect.

I don't know if he ever saw that review, but he must've been thinking along the same lines himself when he recorded his recent Blues For Salvador, his 22nd LP for Columbia. This album kicks my ass around the block every time I give it a listen.

Killer guitar on every cut. Eight of the album's nine cuts are instrumental, featuring Carlos' signature singing, stinging guitar lines. For guitar fans, it's a dream come true; easily his most exciting, most scintillating, most inspired display of ax magic in over a decade. Ah, welcome home, Carlos!

And he's not playing the hits, either. No lame pop structures or hook-laden wimp fare like the highly saleable radio hit Winning from a few years back. No cheesy vocals anywhere in sight.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Sure, sure, it's good to go gold and bring home the bacon. But I just couldn't deal with that limp radio-play pap with the sounds of Abraxas or Caravanserai still fresh in my ears and the sight of Santana burning up the Woodstock stage on Soul Sacrifice still imbedded in my memory banks. That's like munching on Yodels and Ring-Dings after feasting on fine French cuisine.

You drop the needle anywhere on Blues For Salvador and you get the real deal. The man redeems himself for any past lapses. Bailando/Aquatic Park revives the memory of Soul Sacrifice. The lyrical ballad Bella is played with a soulful Wes Montgomery tone that allows the nuance of Carlos' expression to shine through beautifully.

His adventurous guitar synth work on the mood piece Mingus is highly ambitious, if not monumental – or even characteristic. And the sheer conviction that Carlos displays on the title cut, a duologue with keyboardist Chester Thompson, is positively Herculean.

There's more. He stretches like in days of old on the live jamming vehicle, Now That You Know, recorded during his band's '85 World Tour. He burns red-hot on the Latin percussion workout of Hannibal, which segues to a loose, bluesy swing feel at the tag.

He cranks out some vicious wah-wah licks, reminiscent of Jimi in all his glory, on the funky Deeper, Dig Deeper. And he unleashes with a vengeance on 'Trane, which is powered by old-time runnin' buddy drummer Tony Williams.

There may not be any displays of two-handed tapping, wang-bar theatrics or scalar pyrotechnics on Blues For Salvador, but nevertheless, it gets my vote for Top Guitar Album Of The Year. It's a strong statement from a national treasure. And it seems that this powerful, expressive album is now serving as the bridge to a leap in a new direction for Carlos Santana, as well.

''I'm planning to do more of this from now on," the once and future guitar hero explained recently. "I have come to the conclusion – and I don't know why it took me so long, but nevertheless, I'm here now – that a lot of people tell me they don't get enough guitar on my albums. So I decided to do an album where the guitar would be the singer, playing the melody. And it feels really, really good.

"I have come to a point where I'm not afraid to be the main vocal in there. I mean, if cats like Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul can see that I can cut it, I guess I can cut it. It gives me a certain kind of confidence to be able to play with musicians of that caliber. So it's easier for me now to embrace this vision of the guitar being the main, primary vocal."

He's referring to recent collaborations with jazz heavyweights Hancock (Monster, Columbia), Zawinul (This Is This!, Columbia) and Shorter, whom he's been jamming with a lot lately. Those artists tapped Carlos for his unique quality, and his signature sound, not for his knowledge of scales and chord inversions.

They were after the feeling he projects in his playing, the conviction behind his notes. Yet Carlos admits he's at a point now in his career where he would like to learn a thing or two about theory so that he can make the leap to the next level.

"I have been accused of being a very simplistic, very lyrical player, and that's okay. That just comes from the blues, which is my background. But every day you wake up and transcend. You can't ever rest on your laurels. Every day you wake up is an opportunity to go beyond, and that's why I let my band go right now. For the first time in my life I'm just roaming around, vagabonding.

"I'm just jamming a lot these days with guys like Wayne Shorter and Tony Williams. And it feels good because now I don't have the responsibility of maintaining a group... being a baby-sitter, psychologist and all the things that you have to be to be the leader of a band.

"So it's a good time for me. I can afford to go out there and really learn – take some time and just learn some theory or learn how to sing or learn more about harmony and voicings. That's what I need to do right now because I want my vision to be more expanded. I need to know the architectural order of someone like Wayne Shorter.

"For me, listening to his music makes me feel like a two-year-old, like I don't know anything about music. And I need to crawl out of the crib and find how that order relates. I can understand the blues, but I need to learn more cycles. So I'm trying to stretch out a bit on the guitar now, make that leap to a new level. I don't know if I'm gonna succeed or fail, but I'm definitely hungry for it.

"And for me, now, I see the importance of learning more chords, learning to read. Because I have taken it as far as I'm gonna take it. You can only dive into your subconscious so much, but now I really feel it's time for me to do some woodshedding, learn a whole bunch of different inversions and all that kind of stuff.

"I can't really put it into words 'cause I'm really ignorant about all that stuff – flatted fifths and ninths and all that. I play them a lot but I don't know what I'm doing. Well, they say ignorance is bliss, but that's how I play. But just by hanging out and jamming with Wayne Shorter, I'm learning, I'm picking up things and it's helping me to stretch."

Carlos is proud of the fact that he can easily fit into so many diverse musical communities. Of course, the blues fits in everywhere and honest, heartfelt expression is appreciated in any musical culture. Which is why Carlos can get over equally with the likes of John Lee Hooker, Alice Coltrane, Willie Nelson, Rubén Blades and Wayne Shorter.

"There's very few musicians who can do that – go into any part of town and play with anybody. Most musicians, they're very insecure. They only stay in their little pond. Heavy metal with heavy metal, blues with blues. But to me, that would be a curse to stay in one place for too long. Some people like to get a Ph.D. in one subject, but the people who I love are the ones who got a Ph.D. on life – Jimi, Miles, Bird, Gil Evans.

"That's what turns me on most – music. Not just one facet of it, all of it. It's more challenging to mix it up. And you do get scratched once in a while when you jam with other people. But that's all part of it. You have to be bold. You have to go out there and complement what they're saying, [don't] be a hot dog and try to show off how fast or how loud you can play."

Carlos greatly admires artists like Miles Davis and Gil Evans or guitarists like John McLaughlin and Wes Montgomery, not to mention the bluesmen who first caught his fancy, like Otis Rush, Buddy Guy and B.B. King. But he doesn't seem too impressed with the whole new movement of so-called neo-classical metal players who place more emphasis on scales and precision and speed rather than heartfelt expression.

"A lot of aspiring musicians today are playing a lot of notes. It's a technique, an intellectual thing. You can practice this and eventually learn to do it. But it's still a surface thing. What they need to practice to be completely rounded is the stuff that Jimi was doing and Otis Rush and B.B. and Albert Collins and Buddy Guy – with one note you can shatter a thousand notes.

"Especially if you know how to get inside the note. A lot of players don't know how to get inside the note so they're always playing over it. And they use all the same gadgets so they sound kind of the same after a while. They begin to lose their identity, which is the most important thing that they have been given in life.

"Miles Davis was saying that some of these people need to go to Notes Anonymous to learn how to play less. My nephew does that a lot when he plays. It's a different kind of vocabulary. But the thing is, it's teenager music we're talking about there; maybe the 13-to-20-year-old range of listenership for that kind of playing.

"Teenagers don't necessarily like to show their emotions. They don't like to cry in front of people. They like to show off, but they don't like to cry. They don't like to be naked and show their innermost emotions, which is what real music is about.

"When I was a teenager I didn't want to expose my feelings either. You wanna appear macho or cool, so I can understand that. But if you wanna take the long-term as far as being a musician, you have to learn how to cry. Not whine, but cry."

When he speaks about music, he often makes colorful analogies to food, architecture, furniture, other tangible objects. Of fusion music he says, "It sometimes sounds to me like microwave food. I like when people spend the whole day cooking, you know, in the kitchen and at night when you sit down to eat there's a strong, healthy aroma in the room. It has a different flavor and somehow has more meaning that way than just popping Stouffer's in the microwave.

"That's what fusion means to me. It has no love behind it. It's like someone burping on your face or something." Wayne Shorter's architectural compositions, on the other hand, are "like Tiffany glass – very elegant, very elite. Not Woolworth's."

Of Otis Rush's powerful blues playing, he says, "It's pretty hard to beat it, man. The way he bends a note is like sucking on sugar cane. He sucks all the juice out of it, you know? And that communicates to the listener. It's easy to pinch the listener when you bend notes.”

And what about the typical player's addiction to pedals and wireless systems and all those things we put between ax and amp? "It immediately sounds like you're playing through half a man. You lose all the bottom. It's like white wine. I like red wine."

While Carlos feels that the whole new wave of Yngwie clones will eventually go the way of eight-track cartridges, Fizzies and Freddie & The Dreamers, he maintains that someone like John Lee Hooker will never go out of style. In fact, he has plans to expose the bluesman to a wider public in a gala concert performance later this year.

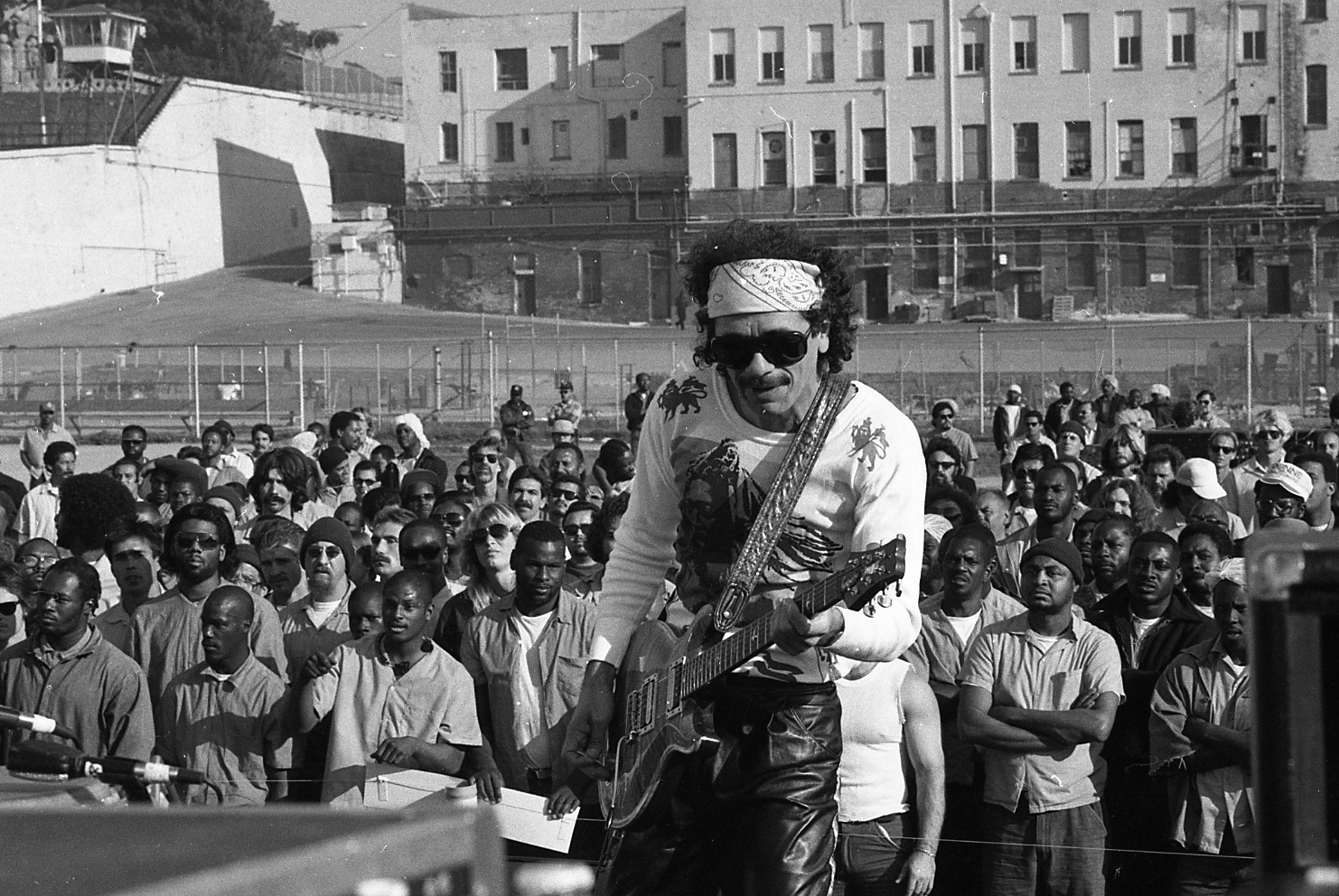

"It's a special one-time thing with the Berkeley Symphony and John Lee Hooker," he announces. "If you can imagine a symphony backing up John Lee doing his music, the cellos doing that boogie-woogie riff. That's been one of my dreams for two-and-a-half years now. Thank God we're finally going to do it.

"I was rejected by just about every symphony in every city in the country. But Berkeley is excited about the project. And I think it's an important project because to me, John Lee Hooker's music is American classical music. And that shit must be preserved, man.”

So Carlos is taking his own advice from the lyrics of Deeper, Dig Deeper, one of the few killer tracks on his disappointing Freedom album: "You have to trust your inner pilot/Let your feelings flow." He's out on a limb, soaking up stimuli from the likes of Wayne Shorter and Tony Williams and others. ''I'm learning all these new languages," he laughs.

"We just did a jam in San Francisco with Jerry Garcia and Wayne and the Caribbean All-Stars and the Tower Of Power horns, and it all fit, man. Then the next week we did a benefit concert for Jaco Pastorius' family with Peter Erskine, Marcus Miller, Victor Bailey, Hiram Bullock, Herbie and Wayne. Again, we all jammed together and it all fit. I was like in a trance. I found myself directing the whole thing, conducting the flow of traffic. So it shows me that all music comes together."

Carlos is living for the music now. He's taking his time and checking things out, always open to new influences and directions. We may not hear the results of his current search until late this year, but if cuts like 'Trane or the title cut from Blues For Salvador are any indication of the path he's heading down, I say 'keep on, Carlos.'

He puts his ax down and turns contemplative. "You know, entertainment is fickle. And that's what I would suggest youngsters take notice of.

"A lot of the bands around today are doing entertainment, not making music. It's like a Las Vegas act or something. But real music. I'd rather listen to real musicians on the street in front of Macy's around Christmastime than a lot of the MTV stuff that I'm hearing. 'Cause those guys in front of Macy's are really playing. They're hungry and they can feel it. And that has always been my priority… feeling."