“Some bass parts are functional and some are creative: you don’t need to play Rachmaninoff when the band wants Al Green”: The man behind Elvis Costello’s finest albums recalls his life as a main Attraction

Bruce Thomas, once of Elvis Costello’s backing band, the Attractions, recounts his career

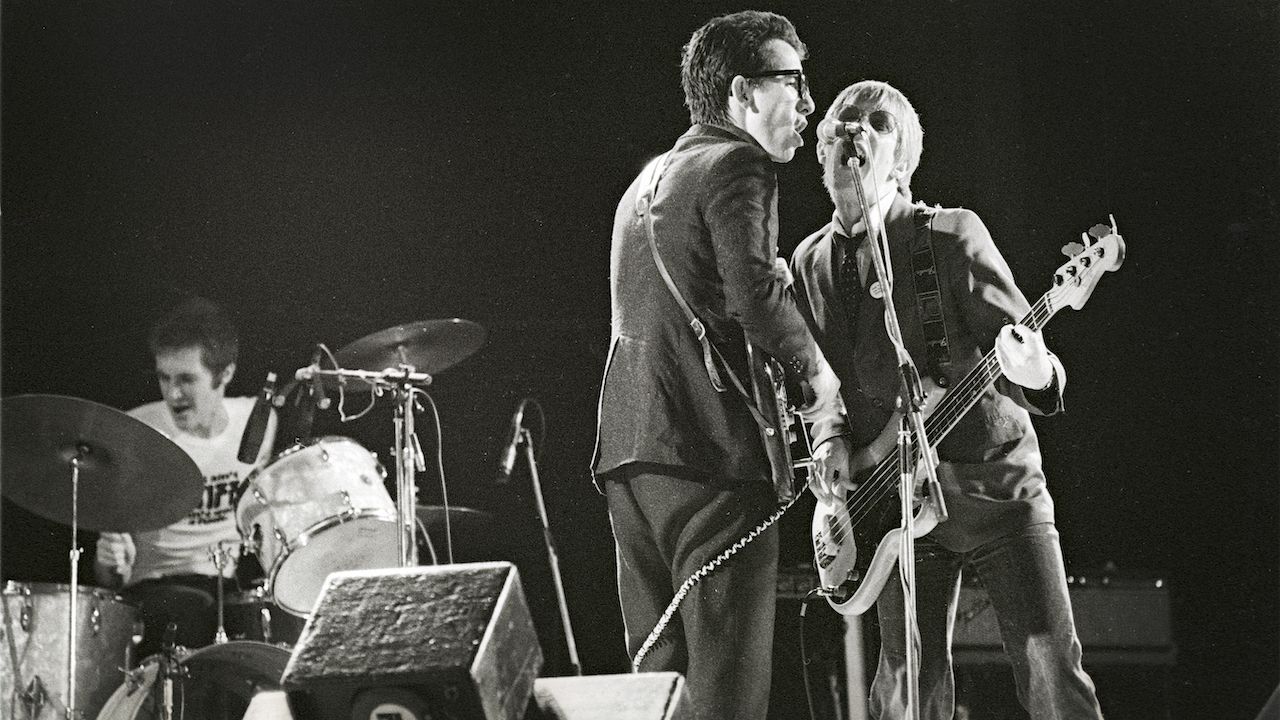

Elvis Costello emerged as part of the punk/new wave music revolution that exploded during the mid-1970s. While his debut was largely a guitar-centered affair, the sonic core of his second album, This Year's Model, consisted almost entirely of drums, bass guitar, and keyboards, marking the beginning of a long and illustrious collaboration with his backing band, the Attractions.

In fact, it’s almost impossible to imagine Costello’s best work without Steve Nieve on keyboards, Pete Thomas on drums, and the dynamic and inventive bass playing of Bruce Thomas. Songs like Pump It Up, and (I Don't Want to Go to) Chelsea sound like they were essentially written from the rhythm section up. “Generally I took my melodic cues from the vocals, and my rhythmic cues from the drums,” Thomas told BP. “Some bass parts are functional and some are creative: you don't need to play Rachmaninoff when the band wants Al Green.”

For a look at the band at the peak of their early onstage powers, check out their act of punk defiance from their December 1977 appearance on Saturday Night Live or their showcase on the German TV show Rockpalast the following year.

Back in July 2016, following the release of his Bass Centre Profile signature bass, the man behind Elvis Costello’s finest albums checked in with BP to talk about his life as a main Attraction.

When did you start playing bass?

“I started playing in 1965, which was the most creative year in pop ever, if you think about Dylan and the Kinks and the Beatles and so on. That year, it was one great record after another, week after week. In my school everybody was learning to play guitar, but bass appealed to me, mainly because it only had four strings, which were wider apart so you had a better chance of hitting the right one. I also liked that part of the sonic spectrum, especially as you had James Jamerson, Paul McCartney, Duck Dunn and John Entwistle at the time, who I considered the four pillars of modern bass playing.”

What happened next?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I made myself a copy of a Höfner violin bass because I couldn't afford to buy a real one, and started playing in bands. I played in the Roadrunners when I left school: that band featured Paul Rodgers, who went off to form Free. I then played in a prog band called Bittersweet for a week in France, then in a band called Village with Peter Bardens, who founded Camel. Then I was in a band called Quiver, who had a couple of hits, and then a band called Moonriser, and then I auditioned for the Attractions, Elvis Costello's band, in 1977. I stayed with Elvis for 10 years and recorded nine albums with him.”

“That band had a very modern image, so I had to get a haircut and have my trousers taken in! I'd been through every kind of band, but that's what happened back then: musicians would wear black T-shirts and sneakers one week, and their mother's curtains the next. It was no different to Spinal Tap.”

Did Costello give you much direction about the bass parts?

“I'd been playing bass for 10 years, so Elvis caught me at the right time. He didn't give me direction about the bass parts: in fact, he claimed he never listened to the bass! I’m a firm believer in the theory that you need to do something for 10,000 hours or 10 years before you become truly competent at it. That applies to all the things I've done – whether it’s bass playing or martial arts training.”

What bass were you playing back then?

“The first bass I used as a professional was an Epiphone Rivoli, and then I played a Fender Precision, and after that I went back to another Rivoli. Then I had a Fender Mustang, a Danelectro Longhorn, a Hagström eight-string, a Fender Vl and several different P-Basses. I had a Gibson Thunderbird for one gig, and a Hamer for another. My main basses were Precisions, though. My favorite one for recording was the Danelectro, for live, it was my salmon pink P-Bass, which was stolen in the 1990s, and now my signature Bass Centre Profile.”

Tell us about your signature bass.

“When my salmon pink Precision was stolen, I went to Barry Moorhouse at the Bass Centre in London for a replacement. I tried a few 1960s P-Basses, but none of them were ever quite right. I'd fiddled around with my Attractions bass so much, shaving down the neck and so on, that the only two options were either to get a Precision and make the same modifications again, or start from scratch and build a new model to my specifications. Barry suggested a signature model for me: I'd never had a signature bass before that, although it was vaguely discussed with Fender at one point. So he gave me a couple of their basses and I went out in the back garden with a sander: he's really good with necks, so we just kept making it thinner and thinner. It's beautiful.”

What about amps?

“I went through a few amps, too: first Marshall and Park cabinets, then a Fender 18-inch cab. With Elvis I played Peavey gear, although I had 15-inch cabs, which I didn't like because they're neither as deep as 18-inch ones or as toppy as the 10-inch. I had a Traynor Mono Block too, but the amp I used most was the Ampeg SVT. I had Johnny Winter's old guitar amp as well: they sounded great with a bass. After that I went to Trace Elliot.”

Do you use any effects?

“I never really used effects, although on the last tour we did I used choruses, octave-droppers, delays, all kinds of things, because we did a kind of Jesus & Mary Chain-style song called Poor Napoleon where I stamped on everything. But the only effect I really set store by was compression: I used the one in the Trace Elliot amp, or a Boss graphic pedal. I like a middly bass sound, because I want each note to stand out, and Elvis had a very middle voice so the two sounds would fight against each other – which was a source of creative tension at times.”

How has the music industry changed over the years?

“In the old days there was one studio in the northeast, recording live in mono. Today you can work on a laptop which makes a £500,000 Synclavier look like a toy. Anyone who can afford a laptop is a producer now – and the same goes for authors and musicians! It's a brave new world!”

Nick Wells was the Editor of Bass Guitar magazine from 2009 to 2011, before making strides into the world of Artist Relations with Sheldon Dingwall and Dingwall Guitars. He's also the producer of bass-centric documentaries, Walking the Changes and Beneath the Bassline, as well as Production Manager and Artist Liaison for ScottsBassLessons. In his free time, you'll find him jumping around his bedroom to Kool & The Gang while hammering the life out of his P-Bass.

“I asked him to get me four bass strings because I only had a $29 guitar from Sears”: Bootsy Collins is one of the all-time bass greats, but he started out on guitar. Here’s the sole reason why he switched

“I got that bass for $50 off this coke dealer. I don’t know what Jaco did to it, but he totally messed up the insides!” How Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan went from buying a Jaco Pastorius bass on the street to fronting one of hardcore’s most influential bands