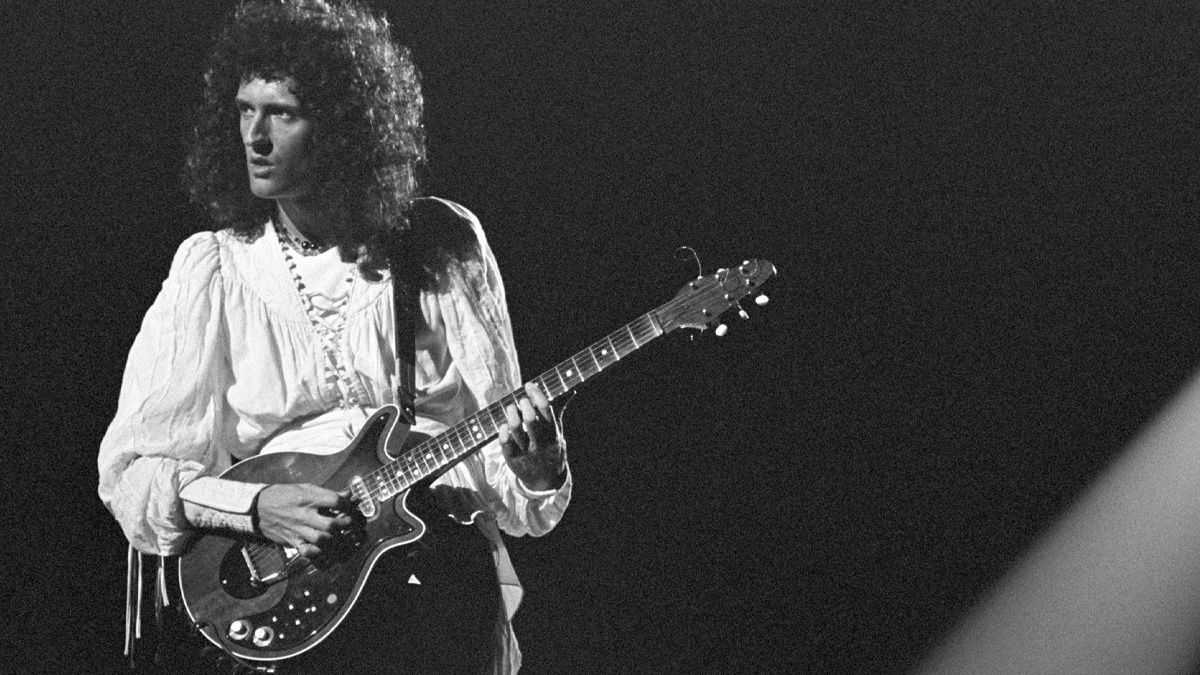

Brian May – the ultimate interview: the Queen legend reflects on his career highs and lows, songwriting with Freddie Mercury and 50 years of trailblazing guitar playing

In this career-spanning interview, one of the all-time greatest guitar players talks through every era of Queen's career, and charts the evolution of rock's most singular band

A new year brings another landmark in the life of one of the greatest guitar players of them all. “50 years,” Brian May says with a smile and brief pause as he takes it all in. “It really is amazing when you think about it.”

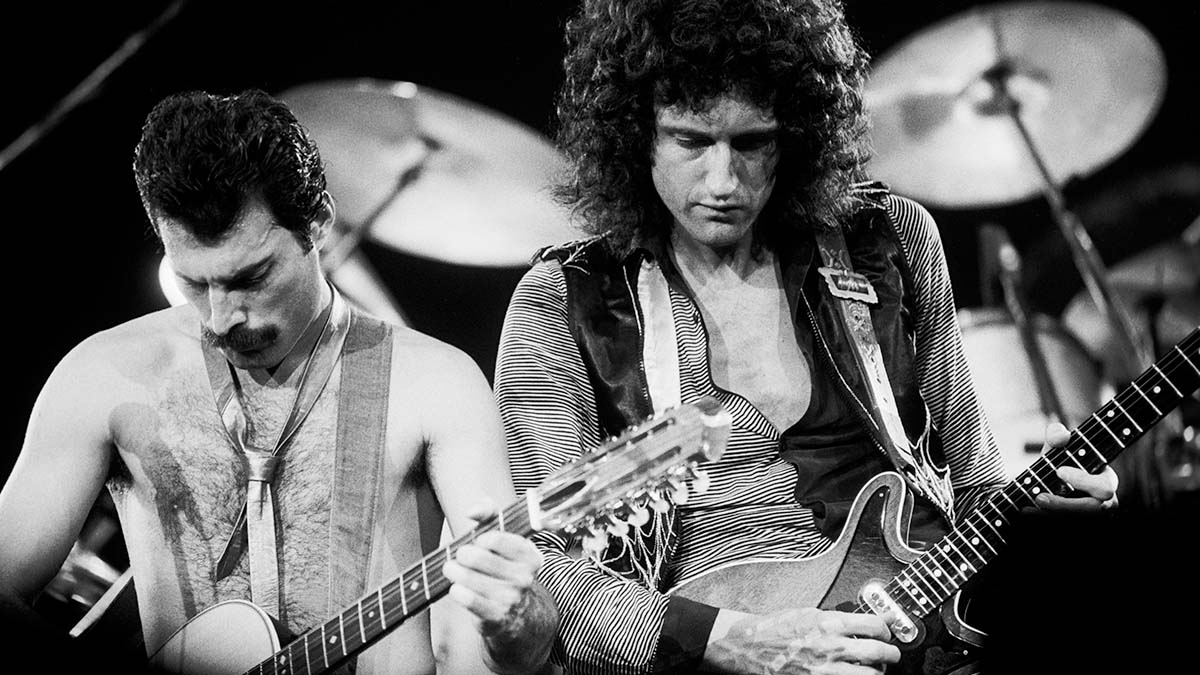

Half a century ago, the release of Queen’s debut album was the beginning of an extraordinary journey for Brian and the three other founding members of the group: drummer Roger Taylor, bassist John Deacon and singer Freddie Mercury.

That first album, titled simply Queen, was not a success, peaking at number 24 on the UK chart. But by the end of 1975 they had their first global smash hit with Mercury’s operatic rock masterpiece Bohemian Rhapsody, which held the number one spot in the UK for nine weeks, with a groundbreaking video that was years ahead of the MTV revolution. And from there, world domination soon followed.

Queen’s stats are astonishing. More than 300 million record sales worldwide, including six million of their 1981 collection Greatest Hits, making it the biggest selling album of all time in the UK. More than one billion streams of Bohemian Rhapsody on Spotify alone. But those numbers are only a part of the story.

The music made by the original line-up of Queen between 1973 and 1991 was dazzlingly creative, and as wide-ranging as it was far-reaching, encompassing everything from heavy rock to disco, gospel, funk and synth-pop.

The big hits came from every member of the band: Mercury with Killer Queen, We Are The Champions and Crazy Little Thing Called Love as well as Bohemian Rhapsody; Taylor with Radio Ga Ga and A Kind Of Magic; Deacon with Another One Bites The Dust and I Want To Break Free: May with We Will Rock You, Fat Bottomed Girls, Flash and I Want It All.

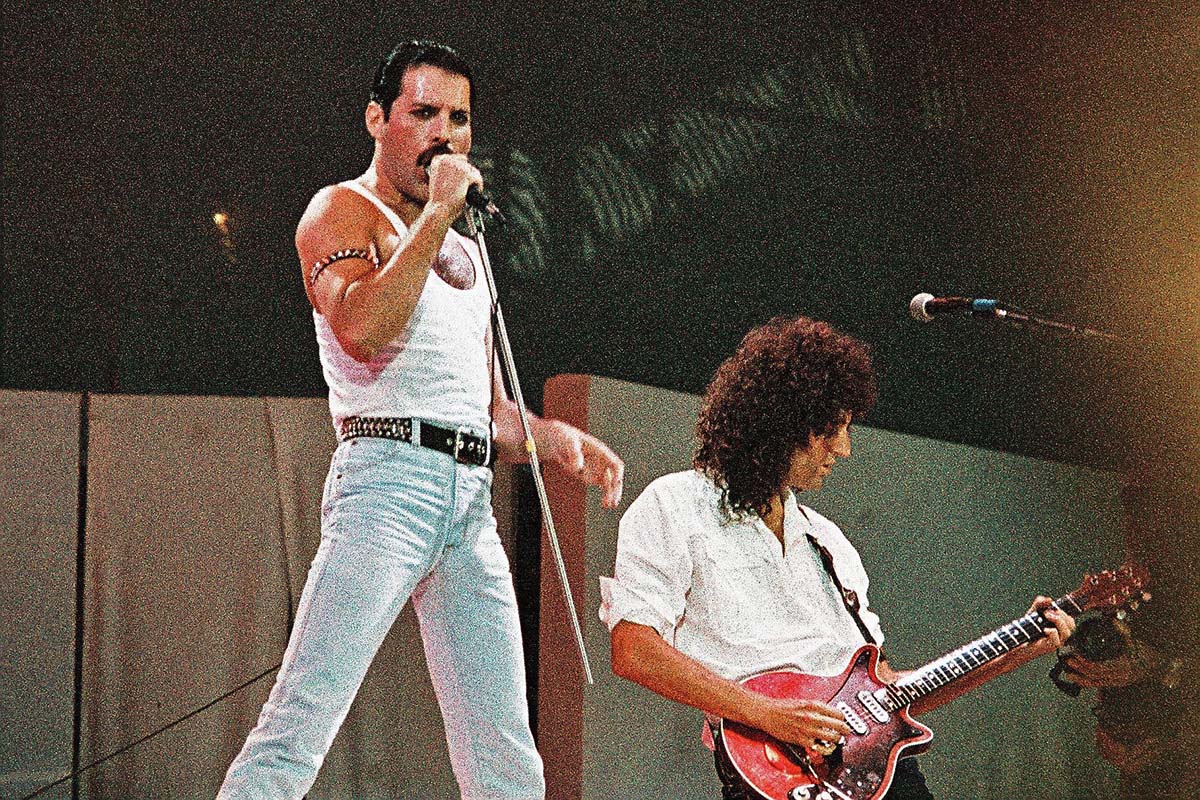

And as a live act, with Mercury a hugely charismatic frontman, Queen were the masters of stadium rock, as they proved in 1985 when they stole the show at the biggest music event in history, Live Aid.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In November 1991, the death of Freddie Mercury at the age of 45 was the end of Queen. Or so it seemed. In the following year, memorial concert staged at Wembley Stadium, the scene of Freddie’s greatest moment at Live Aid, saw May, Taylor and Deacon performing Queen’s classic songs with an all-star cast including David Bowie, Elton John, Robert Plant, George Michael and members of Guns N’ Roses, Def Leppard and Metallica.

Soon after, John Deacon retired. But for Brian May and Roger Taylor there was, over time, a shared belief that Queen was unfinished business. Between 2005 and 2009, they worked with ex-Free and Bad Company singer Paul Rodgers, performing live and recording an album, The Cosmos Rocks, billed as Queen + Paul Rodgers. And in 2011, they enlisted Californian singer Adam Lambert, a runner-up in talent show American Idol, to front a first tour as Queen + Adam Lambert.

Another huge success came in 2018 with the movie Bohemian Rhapsody. Described as a ‘biographical musical drama film’, and starring Rami Malek as Freddie Mercury, it grossed over $900 million. And with each successive tour, Queen + Adam Lambert have played sold-out shows all across the world. The Rhapsody Tour, which wrapped last summer, included no less than 10 dates at London’s O2 Arena.

In a solo you want to hear the personality, the attack, and the feeling in the moment

So it is that after 50 years, Queen’s music remains as popular as it ever was. To mark this anniversary, Brian May is speaking to TG from his home in Surrey, where he sits in a surprisingly small and sparsely furnished office room.

In a lengthy conversation, he talks primarily about the songs he wrote for Queen, from Keep Yourself Alive, the powerful opening track on the band’s debut album, through to The Show Must Go On, the poignant grand finale from Innuendo, the last Queen album of Freddie Mercury’s lifetime.

Brian’s gear is well documented. The homemade Red Special guitar and the AC-30 combo amp have been his trusted tools in the vast majority of recordings from his long career. As he said last year, in a separate TG interview: “I’m so lucky that my guitar and amp have such a wide range of possibilities.”

So in this new interview, the focus is on his development as a player, the key influences that shaped him, his education in the techniques of recording and production, his approach to live performance, and the art of songwriting in all those classic he created - channelling Led Zeppelin in Now I’m Here, inventing thrash metal with Stone Cold Crazy, matching the epic scale of Bohemian Rhapsody with The Prophet’s Song, and composing the mother of all rock anthems in We Will Rock You.

And he begins by taking us all the way back to that first Queen album...

In the year of ’73...

As the four members of Queen prepared to go into the studio to record the band’s debut album, what kind of guitar player were you aiming to be?

“What a great question! It was a combination of all the things that were in my head, starting from when I was a kid and listening to the birth of rock ’n’ roll on my headphones - in my bed, hidden under the covers. And then there was everything that came in the late 60s. So it’s a combination of Buddy Holly, James Burton, Hank Marvin, and then Jimi Hendrix and Jeff Beck and Pete Townshend. All the people who are still my heroes.

“When I look back on it, I don’t think I could have been born at a better time. As kids we were so lucky to have grown up in that period when things were bursting through and all the boundaries were being broken.

When I first heard Little Richard, it was a moment of shock, but there was also the joy of realising that people could actually sing that way

“When I first heard Little Richard, it was a moment of shock, but there was also the joy of realising that people could actually sing that way – they could scream their emotions, as opposed to being a smoothed-out crooner or whatever. It wasn’t just singing tunes anymore. It was singing your passion, your anger, your love and your pain.

“It was such a different world before rock ’n’ roll, and both Freddie and I had a lot of influences from what came before, the jazz stuff like Glenn Miller and The Temperance Seven. So when we were growing up, those influences were in us as well as the emerging rock ’n’ roll, and that gave us a perspective that almost nobody has these days.”

The first album

Queen’s debut album was co-produced by the band with Roy Thomas Baker and John Anthony, and recorded at Trident Studios in London, with additional material from earlier sessions at another London studio, De Lane Lea. What did you learn from that whole experience?

“Our major frustration was the sound of that first album, which we were never happy with. We were thrown into the studio and into a system which regarded itself as state of the art. Trident Studios were very emergent as a force in the world. And they thought they had it down.

“But the Trident sound was very dead. It was the opposite of what we were aiming for. So Roger’s drums would be in a little cubicle, and all the drums would have tape on them. They’d all be dead and down. I remember saying to Roy Thomas Baker, ‘This isn’t really the sound we want, Roy.’ And he said, ‘Don’t worry, we can fix it all in the mix.’ Which of course is not the best way, is it? And I think we all knew: it ain’t going to happen!

“Strangely enough, the demos we’d made at De Lane Lea Studios in Wembley were closer to what we dreamed of – you know, nice open drum sounds and ambience on the guitar and everything. That’s much more the way we wanted it to go. So that’s the major frustration with the first album.

“But there were other frustrations. Roy was doing a great job of kicking us into shape, but it didn’t really sit very well with our way of playing. His idea of getting on track was do it again and again. And again. And again. And again! So there’s no mistakes. But of course, by the time you’ve done that, you’ve lost all your enthusiasm for it. And it kind of shows.

“Much later we evolved these techniques of keeping ourselves fresh – particularly with The Game album [1980], where if the backing track sounded good, and you make a mistake, you’d just drop in on it. Then we said, ‘Why didn’t we do that before?’ And it was because people told us it couldn’t be done. But with those backing tracks on the first album, they got a bit tiresome. And I think you can hear it in some cases.”

How happy were you with the guitar sounds on the album?

“That was a bit of a fight as well, because people had discovered multi tracking, and there was this feeling that everything ought to be multitrack. So you play a solo, and the first thing people say is, ‘Oh, do you want to double track that?’ And maybe you do. But maybe you don’t – because sometimes you want to hear the personality, the attack, and the feeling in the moment when you do that one track.

“So there was an awful lot of overdubs on that first album, which I would say now was unnecessary, and perhaps made it a bit more stiff than it otherwise would have been. Having said that, I think the songs are very representative of where we were at the time.

“We were evolving. We had our heroes, as people always do. Anyone who tells you that they create in a vacuum is not telling the truth, because you have to create according to what you’ve grown up with. And I’ll mention Buddy Holly again, because he was such a big influence on me. That’s what got me excited in the beginning, I guess. But you can hear in the first album that we’re finding our style.”

Despite its difficult birth, are you proud of that album?

“Oh, I love it! It encapsulates what we were at the time, and it’s a declaration of where we were going. It’s very emotionally-based and quite raw. But it’s got a lot of melody and sh*tloads of harmonies. We were starting to flex our muscles. We were painting those colours with vocals and with guitars. It’s got all sorts of experimentation, which defines how free we wanted to be.

“There’s one song, The Night Comes Down, where we’re doing something which people told us we couldn’t do. People in those days used to say, ‘You can’t mix electric guitar with acoustic guitar.’ Nowadays that sounds pretty funny, but it was a belief that people around studios had, you know?

“They would say the electric guitar is too loud for the acoustic and I went, ‘Come on!’ It’s just a question of balancing in the mix. So with The Night Comes Down, it’s based on acoustic guitar, my old beautiful old acoustic. But the guitar harmonies are all electric. And that was a beginning, sort of like a demonstration: ‘Yes, we can do this, we can make our own rules!’ So, yes, I like that first album, because it does define us. Absolutely.”

Keep yourself alive

As the first track on the first album, Keep Yourself Alive was effectively the band’s mission statement. Was this also an important statement for you personally as a guitarist?

“Keep Yourself Alive, you could write a book about in itself. It’s got the first multitracked solo that I ever did. And I am happy with it. It’s a song written by a boy who’s becoming a man. It was meant to be ironic, but I discovered that irony isn’t an easy thing to put into music, because people don’t tend to connect with it. They tend to take it at face value.

“Keep Yourself Alive wasn’t meant to be jolly. The message was meant to be: if keeping yourself alive is all there is, then what is life? That’s kind of where I’m coming from. But people took it as something very joyful. And to be honest, I haven’t fought that, because it’s kind of nice. It seems to give people an uplift. All songs evolve after they’ve been made, not just before they’ve been made, and that’s one of them, I think.”

With this being such an important song, did you work that little bit harder in the recording and mixing of it?

“I’ll tell the whole story. We first put the song down in those demos that I told you about at De Lane Lea, and I was very happy with it. But of course we needed to re-record it for the album, and you know, when you’re trying to recreate something, it’s never quite the same. I never felt that the album version had the original ebullience that we got when we were first putting it down. But we worked on it very diligently.

“A lot of the multi tracking rhythm parts that we put in, I took off, but we couldn’t mix it. We had Roy Baker, who is an absolutely first class engineer, and was quite experienced by that time. He’s the guy who did All Right Now for Free. We had John Anthony, who had great ears as a producer. And then we had the four of us who are very precocious boys. And between all of us, we couldn’t mix it. It just never sounded quite right.

“But then, one night, I happened to be left alone with the guy who was making the tea, and just becoming an assistant engineer – Mike Stone. I said, ‘Should we just have a go?’ Because that’s the way it worked in those days. For guys like Mike it was an apprenticeship. They would sign on as tea boys and at night times they’d go in and work the desk and learn their trade. Well, he stepped up at that moment!

“The two of us worked through the night and produced a mix of Keep Yourself Alive which suddenly everyone was happy with. So that’s quite a story and that was part of Mike Stone’s blossoming. He became the most incredible producer and engineer. He worked with us on A Night At The Opera and A Day At The Races, We Will Rock You and We Are The Champions. Mike became a very treasured member of our family.

So I do like that mix of Keep Yourself Alive. Really, the stuff we had in Trident Studios was incredibly primitive. We only had left, centre and right for a start when you’re mixing, and you can hear that. Pan pots weren’t invented, basically. You’re mixing to three buses, and there’s very limited outboard gear, so the phasing isn’t some machine, it’s real – you feed out your signal into a Revox in one corner, and you feed the tape over here to another Revox. I’m talking about the delays.

But all that phasing is real – real tape phasing. But apart from that, there isn’t much in the way of outboard gear. There’s very primitive echo chamber like a plate which sits over behind the wall someplace. So, limited capabilities of the gear. But we had a lot of enthusiasm and a lot of will to make this thing sound epic.”

The second album and their first hit

You returned to Trident Studios to make Queen II, and retained the services of Roy Thomas Baker, who worked as Queen’s co-producer on three more albums in the 70s. After the difficulties with the first album, what was your approach second time around?

“I remember saying to Roy as we were going back in: ‘We don’t want it to sound like that first album. We want to sound like we’re in a room and it’s live and real. We have to get rid of all that tape and get rid of the cubicles. And we’ll put the drums in the middle of the room, so we hear the room.’

“In that respect, my dad was a great influence. He introduced me to the word ‘ambience.’ He said that’s what was missing on the first album. And that ambience is the world. The noise you’re making can seem very small. You hear a snare drum, it’s very tight and dry. There’s no character to it, really. But you step back, and you hear it in the room, and suddenly you hear a whole universe!”

Like the first album, Queen II was very much a guitar-driven heavy rock record.

“Yes. We used to go on these package tours to places like Luxembourg and Belgium with groups who were popular at the time - Showaddywaddy, the Rubettes and Geordie, who of course had Brian Johnson [later of AC/DC] as the singer. We also opened for Slade, and we were the new boys.

“We were the young band who hadn’t had any hits, and all of these guys that had hits. So we felt a bit humble. But all those guys looked at us and said, ‘We’ve heard your stuff, and you’re not pop, you’re not glam – you’re a rock group. You’re something which we wish we were.’ Now that was a real shock to us. We didn’t realise that people were already regarding us as something special.”

And it was a track from Queen II that gave you that first hit, when Freddie’s song Seven Seas Of Rhye reached number 10 in the UK.

“Well, you know, of course, that Seven Seas Of Rhye was the last track on the first album, in embryo – a sort of statement that something’s coming. But yes, the finished version was the first hit. Not that big, but the first hit.”

Seven Seas Of Rhye is also quite unconventional for a hit single. It’s not verse/chorus/verse, and it’s got those little instrumental key changes in there. Were you surprised when it made the charts?

“I think it’s fair to say we were surprised because we’d never had a hit up to that point, and until then it seemed impossible. But with Seven Seas Of Rhye, we worked at it very consciously. We’d thought with Keep Yourself Alive: this is going to be on the radio, it’s going to be our first hit. But on the whole, people at radio didn’t play it. We said, ‘Why are you not playing our record?’ They said, ‘Well, it takes too long to happen – the intro is too long.’

“We didn’t get into the verse until 30 seconds or whatever, and for a hit single everything needs to grab you quickly. So we said, ‘Right, our next single will deliver what you people are asking for!’ In other words, everything will happen in the first five seconds, and with Seven Seas Of Rhye it does. It’s like the kitchen sink is in there – a little piano and wham, bang, harmonies, guitar harmonies, massive drum fills – everything! So it was designed to knock people dead in the first few seconds on the radio, and it worked. People went, ‘Okay, yeah, we’ll play that.’

Suddenly, we were an act that people would consider putting on the radio. And we liked it because we hadn’t compromised

“Your hits were all about radio in those days and very little else. So yes, it was designed that way. But at the same time, we were not compromising on the content of the song. It’s very rock. It’s not very pop, and as you say, there’s all kinds of little intricate changes in there. It’s quite a composition, really. And it was quite interactive between the four of us.

“Freddie decided he didn’t want to say it was written by anyone else but him, which is fair enough, because he wrote the lyrics. But it was a very co-operative thing in those days. And I do feel proud of it. I think it’s a good rock pop creation.

“And it got us to that first rung of the ladder. Suddenly, we were an act that people would consider putting on the radio. And we liked it because we hadn’t compromised, because it wasn’t just a kind of soft pop song. It was something also that we could take on the road and be proud of.”

And really, the magic of that song is in those key changes. They have an uplifting quality.

“Exactly. It’s a journey. We wanted to take people off into the stratosphere. It’s always been that way with us. We were inspired by our heroes to do that, and I put The Who way up top of that list. Pete Townshend is the master of mood change, a master of the suspended chord. I owe so much to him.”

Brighton Rock

The third album, Sheer Heart Attack, from 1974, is widely viewed as the band’s first classic and the first quintessential Queen album. And the opening track, Brighton Rock, is one of your most defining songs as a guitar player. It’s an explosion of excitement – and of course, the delay effect is in there. It’s said that this song was written around the time of Queen II, but was held back for Sheer Heart Attack. What was the reason for that?

“It was a slow burner, that song. It took shape gradually. And the solo stuff originated in a different place. When we were out on tour with Mott The Hoople, I played the beginnings of that solo in the song Son And Daughter, which is on the first album.

I started off with one delay, and then realised that if I had another delay of the same length, I could get three-part harmonies, and that’s when I got really excited!

“And I built my own delays – I modified some Echoplexes and built long rails for them so I could produce those long delays. They were frighteningly unstable. They weren’t roadworthy. So it was touch and go where they would work every night. And they didn’t work every night!

“I would experiment at that point with the delays, and got the idea of building up harmonies and counterpoint with the delays. It became an obsession, which actually is still there. I still find I’m sort of obsessed with this kind of stuff. These days, the delays are done digitally very easily.

“But there’s a certain charm about the old tape delays. They didn’t have a certain sound, because I started off with one delay, and then realised that if I had another delay of the same length, I could get three-part harmonies, and that’s when I got really excited!”

When did you switch to the to the double delay?

“I don’t remember exactly, but I think soon after the first album. As soon as we were out on tour – seriously on tour – I had the two delays.”

So it’s fair to say that people have never really heard Brighton Rock without the two delays?

“No, probably not. It’s just one on the album version. But by the time we get to [1975 album] A Night At The Opera, it’s a staple thing. There’s a lot of it in that album, and we’re doing it with the vocals as well in The Prophet’s Song – getting Freddie in there with the same kind of gear and encouraging him to experiment as well.”

Now I'm Here

In addition to Brighton Rock, the Sheer Heart Attack album has another of your signature songs in Now I’m Here – powered by those long, winding riffs, in which there’s an echo of Led Zeppelin’s Black Dog...

“I owe a lot to Jimmy Page, of course – the master of the riff, and the master of getting lost deliberately in time signatures. I think that song was inspired, definitely, by the spirit of Zeppelin. All those wonderful things that are happening when Bonzo [Zeppelin drummer John Bonham] is throwing in things which sound like they’re in a different time signature – that stuff has always fascinated me.

I would never be ashamed to say that Zeppelin were a huge influence on us, not just musically, but also in the way they handled themselves in the business, without compromising

“Those guys were not far ahead of us in age, but the first time we heard Zeppelin, we thought, ‘Oh, my God, this is where we’re trying to get to, and they’re already there!’ So in a sense, there were times when we felt like we’d missed the boat – like we wouldn’t be able to get our stuff out there. But our vision was slightly different from Zeppelin, musically. It’s more harmonic and melodic, I suppose.

“But I would never be ashamed to say that Zeppelin were a huge influence on us, not just musically, but also in the way they handled themselves in the business, without compromising. The way they handled their image, the integrity, the way they built their stage show – so many things. I suppose between Zeppelin and The Beatles and The Who, you would see where we came from. That was the kind of platform that we bounced off.”

Stone Cold Crazy

And yet another landmark track from Sheer Heart Attack is Stone Cold Crazy, a song so fast and heavy that Metallica’s version of it made perfect sense. Is this the definitive example of Queen at their heaviest?

“I think so. Stone Cold Crazy goes back a long way. It was one of the first songs we ever played together, so it’s interesting that it never made it onto a record until the third album. That’s quite unusual, isn’t it? I think we were playing Stone Cold Crazy in our very first gigs.

“Freddie had written the lyrics with his old band, and the original riff was very different – it sounded like the riff in Tear It Up [from 1984 album The Works]. So that original version of Stone Cold Crazy sounded like a lot of other things which were around at the time, with quite an easygoing riff. It didn’t have much pace to it.

“But I thought: these lyrics are kind of frenetic, so the music should be frenetic as well. So I put this riff on it, which people are telling me is the birth of thrash metal or something! I don’t know about that. But was unusual at the time to play at that pace.

“That song was a bit of fun, really. I don’t think we regarded it as that serious, which is perhaps why it never made it onto an album until number three. But it’s nice and heavy. I still remember going in to do the definitive version of it, and it was faster than ever – we just went for it! There’s a lot of adrenaline: let’s go for it! It really does burn. And I liked the sounds that we had in place by that time.

“Stone Cold Crazy is a good example of us recording in a live atmosphere but in the studio. And we started to have it down by that point. Once you get a grip on that kind of stuff, you can fool yourself into thinking it’s live when you’re in the studio. So it doesn’t sound calculated – it sounds real and spontaneous. And we captured it. I think that’s all one take. It’s not like messing around doing take after take. We just did it. I’d say that’s when we started to master the studio.”

The Prophet's Song

On the most iconic Queen album, A Night At The Opera, there is a clear parallel between two grandiose, multi‑movement songs: Freddie’s epic, Bohemian Rhapsody, and your epic, The Prophet’s Song. And it’s evident that The Prophet’s Song is one of yours, because it really rocks.

“To be honest, I always regard it as a bit of a shame that The Prophet’s Song got eclipsed – because Bohemian Rhapsody was always going to eclipse everything. So with The Prophet’s Song, it’s kind of a light that got hidden under a bushel. But the positive is that it’s a deep side of Queen, which people get into when they start exploring. It’s a nice thing for them to discover and get excited about. But yes, you’re right, those two songs were kind of parallel.”

Tie Your Mother Down

When it comes to ballsy rock ’n’ roll songs, there is nothing in the Queen catalogue as ballsy and rock ’n’ roll as Tie Your Mother Down, the opening track from the 1976 album A Day At The Races. What do you remember about writing that one?

I wrote the riff to Tie Your Mother Down on a volcanic mountaintop in Tenerife

“I wrote the riff on a volcanic mountaintop in Tenerife. Really. And I thought, what am I going to do with this? And all I could hear in my head was Tie Your Mother Down, which didn’t seem like a reasonable kind of song title. I remember bringing it back to the boys and saying, ‘I’ve got this riff’, which they all liked.

“When they asked what the song was about, I said, ‘All I’ve got is this title – Tie Your Mother Down – which obviously we can’t use.’ And Freddie said, ‘What do you mean, we can’t use it? Yes we can!’

“And I started to think, okay, this is a song about growing up and being frustrated with your parents. And it’s got a sense of humour to it. And it was quite quick to write those lyrics, which I’m quite proud of, because at that point I was still a boy, not quite a man. And that song is the cry of a boy’s frustration.”

It’s a song that feels very free in the performance...

“Yeah, there’s a Rory Gallagher influence there – in the way I’m snapping those strings like that. And I loved Rory. Perhaps I should have mentioned him earlier, because he was a fantastic influence on me. What a wonderful guy he was, in every way.”

We Will Rock You

In 1977, the year of punk rock, Queen responded with News Of The World, an album of shorter, punchier songs – We Will Rock You the shortest and punchiest of all. It is, undeniably, the greatest rock anthem of all time. How did you create something so simple and effective?

“The song was born one night in Bingley Hall in the Midlands. We were a group which was doing quite well, we had a good following, and we had this thing where people insisted on singing along to our songs. And I think we were quite irritated by it!”

Seriously? Why?

“Because we thought: ‘People, just listen. We’re working really hard, so bloody well listen!’ But they were unstoppable. And this particular night, they sang every word to every song, which was rather novel in those days. I mean, I went to a Zeppelin concert and I don’t remember people singing along to Communication Breakdown or whatever they were playing.

“When Zeppelin played, they listened. They banged their heads, and they listened. And I thought about our concerts: why don’t you buggers listen instead of singing? Anyway, that night at Bingley Hall, we came off stage and we all looked at each other in amazement, because all that singing from the audience was so extreme.

“And I said to Freddie, ‘Maybe, instead of fighting this, we should be encouraging it. Maybe we should be harnessing this kind of energy which seems to be happening.’ And we all agreed that this was something really interesting that we should experiment with – letting the audience be a bigger part of the show.

“I thought, what can you ask an audience to do if that audience is all crammed in together? There’s not much they can do except stamp their feet and clap their hands, but they can also sing. And if they can chant, what would they chant? And with that, I could hear it in my head: ‘We will, we will rock you!’

When Zeppelin played, they listened. They banged their heads, and they listened. And I thought about our concerts: why don’t you buggers listen instead of singing?

“I was hoping that this would become something which would catch on. We would have a song which would be led by the audience. So that’s why there’s no drums on there – just the stamping and clapping that the four of us did. Very luckily, we found bits of an old drum riser lying around in the studio in Wessex in North London, which was perfect to stamp on.

“And with the help of Mike Stone, I evolved a whole business of multi-tracking with various prime delays to make it sound huge, but not echoey. There’s no echo on that. So it sounds like you’re in the middle of a thousand people stamping and clapping. Then we put other stuff on it.

“Now, I was very nervous about this, because it seemed like it was kind of over-simplistic, maybe. And I wasn’t sure if it was going to sound like a proper song. But as soon as I heard Freddie singing it, I started to be more confident, because he sounded like a kind of rabble-rouser. It sounded like he was going to encourage the audience to do this stuff. And so it was all aimed towards getting the audience involved. It was aimed towards the live situation. And somehow it worked.”

Did the rest of the band share your belief in this song?

“I remember Roger had severe misgivings about it. And he certainly didn’t want to put it at the beginning of the album. He said, ‘No radio station is ever going to play this! It doesn’t sound like a rock song.’ But I fought that corner. And generally I didn’t win those arguments, but this time I won. So that was the beginning of the album.

“And it was also my thought that we should weld We Will Rock You and We Are The Champions together as a couple. And that worked out very well – partly because those songs both have the same end in mind, they’re both enveloping the audience and involving the audience, treating the audience inclusively – and partly because it just made such sense musically. It just worked so well.

One Vision was a nice way of flexing our muscles and finding a new place

“So that was the beginning of the album, and that was the single – the two tracks together. It was number four in America, a big hit all over, really. And this whole thing changed our lives radically. Because from that point on, we stuck to that resolution – we became a band that encouraged participation. And that’s not the way we started off, but it became a great thing.

“It probably sounds all very obvious now, because everybody gets the audience to clap and sing along, but that’s not the way rock ’n’ roll was in those days. And I think it was a great bolt out of heaven. Looking back, it’s a no brainer – but at the time it was a radical departure.”

In that sense, would you say that without We Will Rock You there would have been no Radio Ga Ga?

“Yeah. And no many things. So many things. And of course, you never know how people are going to react to a song. But you can hope.”

And the guitar solo in We Will Rock You – what was your thinking there?

“I don’t think it was planned. I just wanted to rock! But I did want to break that boundary as well - because everybody puts guitar solos in the middle of the song, and I didn’t want to do that. I wanted this song to happen with the audience, and that would then lead me to the stage, so the guitar solo would be the climax of the song.

I tried to visualise myself on stage: what would people want to hear, and what would I want to feel like

“That was pretty unusual at the time, and I can’t actually think of another song that does that. So that was deliberate. And that little riff that’s in the middle there, I guess it must have been in my head someplace. But when I went in there to play that piece of guitar, I don’t think I actually had a plan.

“We’d played and played through the song and I tried to visualise myself on stage: what would people want to hear, and what would I want to feel like? And I played for a few minutes, and we just picked the bits that we liked.”

Live Aid

It was billed as The Greatest Show On Earth and a ‘global jukebox’, and Queen delivered on both counts. The band’s allotted 20-minute set was cleverly structured for maximum impact, beginning with an abridged Bohemian Rhapsody and climaxing with We Will Rock You and We Are the Champions. And with Freddie at his peak, this was arguably the greatest performance of the band’s career. But at Live Aid it was an unorthodox setup, with a fast turnaround for each act. So did that make it stressful?

“It was kind of the Wild West, because no one had ever done it before. Bob Geldof [Boomtown Rats singer and co-creator of Live Aid] insisted that it was going to be possible, but a lot of people told him it couldn’t be done - that you couldn’t get bands on and off quickly enough. There really wasn’t a precedent for Live Aid. So yes, we were stressed, but there was so much joy and excitement that overrode everything.

“It was a glorious day, a beautiful sunny day. For the opening ceremony we arrived at Wembley Stadium in a helicopter, which was very exciting for us young boys, and when we watched Status Quo open the show with Rockin’ All Over The World, I was sitting in the royal box with Prince Charles and Princess Diana. It was incredible. I mean, Princess Diana had a lot to do with that - she sort of made rock ’n’ roll okay for royalty. It seemed like a new world.

“Right after the ceremony I flew off again in the helicopter to Barnes [in south London] and went to a fair with my kids. And everywhere I walked in the fairground, there were radios on and you could hear Live Aid evolving. So I remember having that incredible excitement in my stomach thinking, ‘God, we’re going to be back there soon doing it’. And when we went back there, yes, there were a lot of nerves, a lot of adrenaline...”

It’s widely agreed that Queen stole that particular show, of course.

“Well, we didn’t go there to do that. We went there to do our bit. I think the whole thing was very pure and genuine. Nobody was trying to capitalise on it. Everyone was there because they were inspired by Bob Geldof in his quest to solve the world’s hunger problems. Nobody had ever done that before, so we all wanted to help. And of course, nobody wanted to wake up the next morning and think that they hadn’t been a part of it.”

What was going through your mind during those 20 minutes at Live Aid? Did you have a sense that this would be a defining moment for Queen?

“I didn’t think when we came off that it was our best performance or anything like that. I was conscious that it was a bit ragged. And I mean, one-offs always are, there’s always bits that you love and bits that you hate.

When you watch Live Aid now, it’s not without its tense moments. The end of Hammer To Fall is very questionable, you know? But nobody cared – because the adrenaline that was flowing in Freddie was pretty magnificent

“This wasn’t something that we’d done on stage time after time. It was a set specially put together for that occasion. And when you watch it now, it’s not without its tense moments. The end of Hammer To Fall is very questionable, you know? But nobody cared – because the adrenaline that was flowing in Freddie was pretty magnificent.

“He, and also the rest of us, benefited from the fact that we had played stadiums before, and very few artists who were there that day had. We’d been to South America and done these incredible gigs in stadiums in Argentina and Brazil. So we had a measure of what it takes to play to 100,000 people rather than a theatre or an arena.

“Freddie, when you watch him now, he looks so full of confidence. And he is. He knows he can do it. He knows that we’ve already done this thing of involving the audience. He knows that he can get the audience on his side, in spite of the fact that nobody had bought tickets to see us. We weren’t on the bill when people bought all those tickets. So that was a step into the unknown. But I don’t think Freddie ever had any doubts.”

And when you’re performing with a singer with so much power, and such a command of the stage, is there something in your mind about how you have to play to back him up? How to play to that level?

“I don’t know. You see, we kind of grew up together very quickly. And we interacted from the beginning. And it was a very natural, organic kind of relationship, but I wasn’t consciously trying to back him up. If I was trying to do anything, it was to be the right foil.

“We were very interactive. You know, Freddie would be very conscious of me on stage, and I would be very conscious of him - in a musical sense, and also a physical sense. Being on stage is a very physical thing. You have a kind of an awareness of each other, and it’s in the placing and the body language and the channels of energy that reach the audience. So we were very much in harmony, without even trying.

“We were a machine which worked. And that applies to the whole band. Everybody has their place. And it just evolved in a way which you couldn’t have put together. It couldn’t have been manufactured. It just evolved. Fortunately, we were the right people to be together at the right time.”

One Vision

The first Queen song released after Live Aid has a triumphant air to it. There is a sense in One Vision that the band has a new energy. Was that the feeling when it was written?

“It was us going back into the studio and enjoying ourselves feeling very free. We also had a film crew in there with us, which actually changed the chemistry quite a bit. I think we were very conscious of the film crew. And when you see that footage, you can tell it’s hard for us to be as relaxed and normal as we otherwise would have been.

“Nevertheless, you see the song taking shape. It’s built around a lyric of Roger’s, which is basically about Martin Luther King, and he also took that idea into A Kind Of Magic [the title track from the band’s 1986 album]. The lyrics in the two songs are similar. So that was our starting point, but it changed when we evolved the lyrics as we went along.

“One Vision was a nice way of flexing our muscles, I guess, and finding a new place. We were back in Musicland [studios in Munich], which was very fertile for us creatively. It didn’t do a lot for our private lives, because we all went off the rails in Munich. But creatively, it was always very good. And it was fun.

“And again, you asked me about this earlier – with One Vision we’re imagining it on stage from the beginning. We’re imagining how this is going to be live, how it’s going to be something that the audience will get into. And we’re sort of designing it as an epic.

“But we couldn’t resist sending it up at the end by singing ‘fried chicken’. It’s nice to have that other side to things, because we always took our work very seriously, but we didn’t take ourselves too seriously. We didn’t allow each other to take ourselves too seriously!”

The Show Must Go On

The Innuendo album was Freddie’s last act. And in the album’s final track there is so much emotion. Can you describe how this song was created, and how you worked with Freddie through such a dark time?

“By now, of course, we’re in a very different place, where Freddie knows that his time is probably running out. Nobody knows for sure. We are also aware of it. And he’s determined that we will carry on. Business as normal. We will go in the studio, and we will forget everything and just be us creating. And it was a great vibe in the studio.

“Fred was very positive in how he managed it. I don’t really know how. Nevertheless, he wasn’t able to be there that much, because physically he was already suffering, and he had to go for his treatments. You never knew when he was going to come back at that time.

“So with The Show Must Go On, I think I listened to Roger and John putting something down and something triggered in my head - this sort of circular riff. After a few days I did a demo of it, with no real words at that point. Then I played it to Freddie, and I said, I have this title, The Show Must Go On, but maybe that’s too corny.

“I said to him, ‘Do you think that’s going to work? He said, ‘Absolutely! It will work. Why don’t we just pursue that?’ And I had a fantastic afternoon with him, just working through that first verse, looking for lyrics and trying to figure out what it was all going to mean.

“Songs are never about just one thing. The Show Must Go On was about a clown who was suffering inside but still had to paint his smile and make everybody jolly. That’s what the song was about. There was no mention of the fact that this might be some sort of allegory about Freddie himself. But I think it was unspoken that we both knew what we were writing. Really it’s about Freddie.

“We had enough lyrics for that first verse, and Freddie said, ‘I’ll come back as soon as I can.’ He didn’t come back for a long time. But the song developed in my head. I started to think, well, maybe he isn’t going to come back. And at the same time, I couldn’t stop myself.

“For some reason, there was an energy coming into me. And I was writing something which I knew was good and I hoped he was going to be able to sing eventually. So I mapped it all out. And that first verse, I split up into two bits, and wrote the verses around what we’d done together.

“Basically, I wrote the whole song around that little fragment which Freddie and I put together. I woke up one morning with this image of butterflies in my head, and I thought I would love to hear Freddie sing: ‘My soul is painted like the wings of butterflies.’

“I thought: this is Freddie. And he’s not going to write it for himself, because he wasn’t going to thrust himself forward in that way, you know? But I can write it for him. I wanted to put those words in his mouth. And it was a gift from God. I don’t even know where those lyrics came from.

“So I presented it all to him the next time he turned up in the studio, and by that time he was suffering a lot. He could hardly stand. I played him some of the demo, with me singing, which went incredibly high and was very difficult.

Freddie was always shouting at me, like, ‘It’s too f**king high! You’re making me ruin my beautiful voice!’

“In the past, Freddie was always shouting at me, like, ‘It’s too fucking high! You’re making me ruin my beautiful voice!’ So I thought he was going to shout at me this time. But he just heard it and said, ‘I’ll fucking do that. Don’t worry.’ So he downed a couple of vodkas, neat, then propped himself up on the desk and worked his way through singing all of that song. And it was amazing.

“I think he did three or four takes, and he absolutely smashed that vocal. It’s like he reached into a place that even he’d never got to before. I remember saying to Freddie, ‘I don’t want you to hurt yourself. You know, don’t force yourself to do this if it’s not going to feel good.’ But he said, ‘I’ll fucking do it, Brian!’ And he did. And it was beautiful. I think it’s one of his finest performances of all time. It’s incredible.”

Queen + Adam Lambert

And so, 50 years on from the first Queen album, the story continues. You’ve said before that you feel that Freddie would have loved the way Adam sings those old songs...

“I’ve heard a billion voices in my life, and I’ve never heard a voice like Adam’s. Time and time again, I can picture Freddie saying, ‘You bastard!’ Because Adam’s range is ridiculous, isn’t it? And so often, I’ve found myself wishing that Freddie and Adam could have gotten together, because they would have had the greatest time. They’re so similar in some ways, personally and musically.”

Could there ever be a new Queen album with Adam?

“Well, we have been in the studio. We did knock a few ideas around in the middle of one of those tours. But it just never quite reached the place where we felt it was going to be right. So we haven’t pursued it so far. That’s all I can tell you.

“So I really don’t know. But I think there’s a bit of a barrier there. I think if people see Queen on a record label, they still want it to be Freddie singing. It could be Jesus Christ on it, but they’d still want Freddie, and I don’t blame people for that. There are people on Instagram who get annoyed with me: ‘Why are you still carrying on without Freddie?’ And I go, ‘Don’t tell me what to do! I do what I feel that I should be doing.’

“There are people who feel like we shouldn’t even be going on stage without Freddie. But I think that would have been very sad, and it’s not what Freddie would have wanted either. He would have wanted us to continue developing. And of course, because we are continuing and developing, it keeps that legacy alive.

“You know, I often have this conversation with Freddie’s sister, Kash. She gets those questions as well: ‘Why are they doing this without Freddie?’ And she completely gets what we’re doing. She says, ‘This is what Freddie would have wanted. He would not want have wanted his songs or the band’s songs to become museum pieces. He would have wanted them to live.’ And that’s what we’re doing. We make the Queen legacy live. Absolutely.

“The last tour we did was fantastic. Probably the biggest arena tour we’ve ever done, and the most exciting in terms of all the shows being sold out and the energy in those audiences. The thing is, people want live music. They need live music. And we’re happy to go on supplying it as long as we can. As long as I’m alive, I’ll be there!”

Chris has been the Editor of Total Guitar magazine since 2020. Prior to that, he was at the helm of Total Guitar's world-class tab and tuition section for 12 years. He's a former guitar teacher with 35 years playing experience and he holds a degree in Philosophy & Popular Music. Chris has interviewed Brian May three times, Jimmy Page once, and Mark Knopfler zero times – something he desperately hopes to rectify as soon as possible.

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83

“The future is pretty bright”: Norman's Rare Guitars has unearthed another future blues great – and the 15-year-old guitar star has already jammed with Michael Lemmo