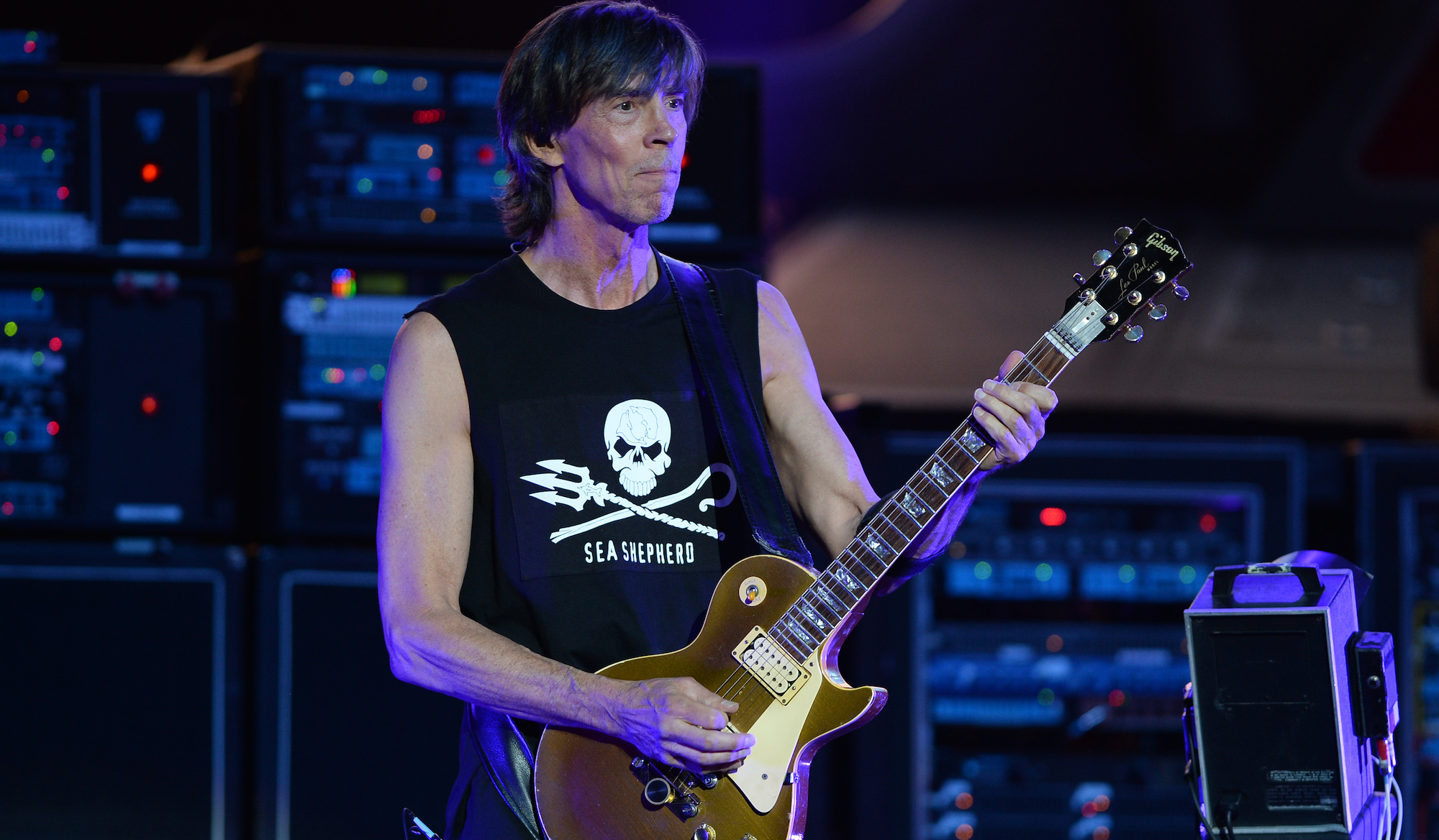

Boston's Tom Scholz: “I was basically a dork that hit the books and liked to build things... somehow I ended up onstage, playing guitar in front of everybody else"

In this 2006 GW interview, the Les Paul-wielding Boston mastermind discusses the trials and tribulations of home recording, sudden success and revisiting his band's seminal early albums

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This interview with Boston guitarist Tom Scholz was originally printed in Guitar World as part of its October 2006 issue.

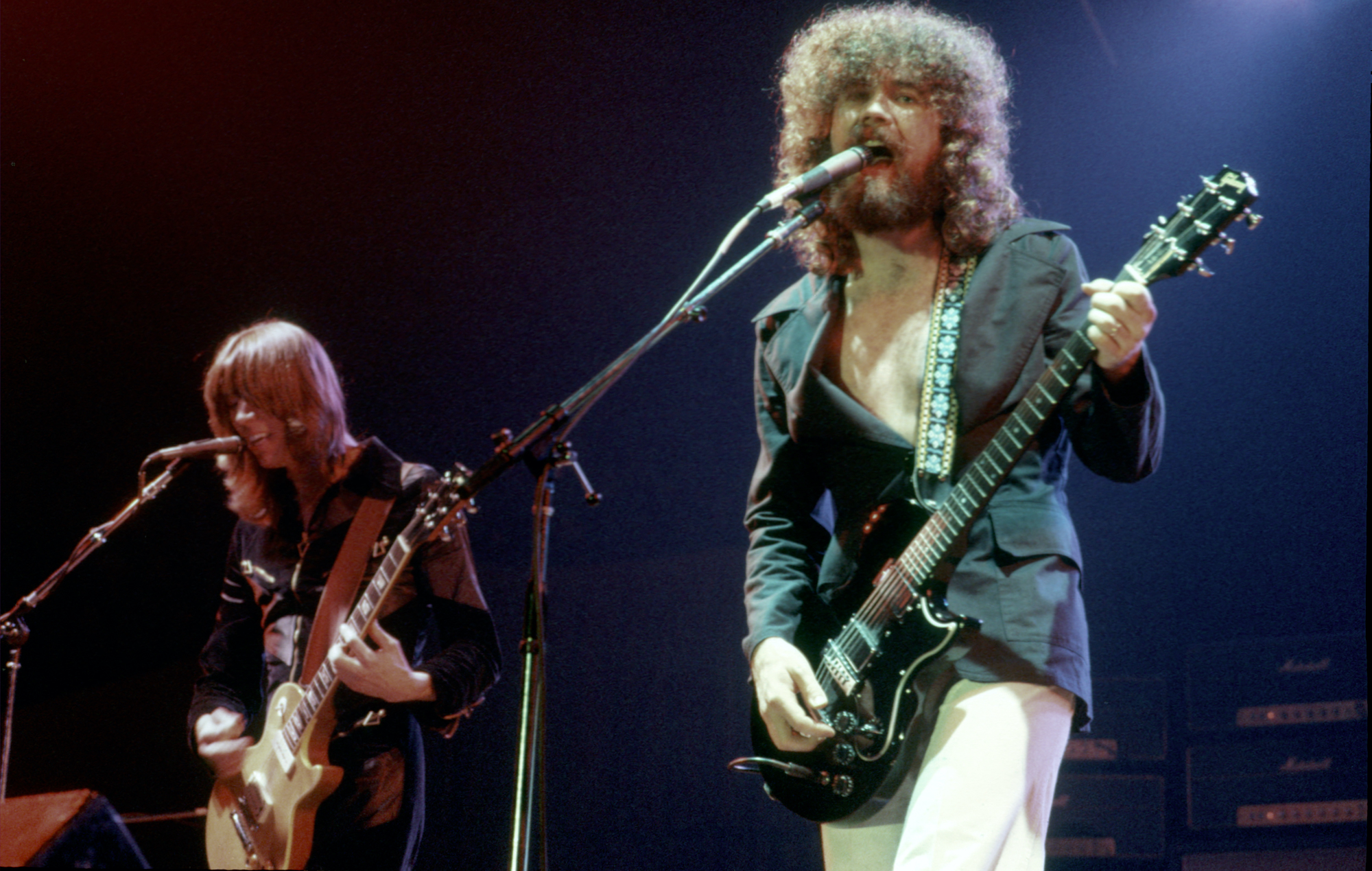

When Boston’s self-titled first album was released in the fall of 1976, few industry insiders thought that a guitar-heavy rock record could make much of a dent in the charts, much less become the best-selling debut of all time.

“Everybody thought that it was impossible, because disco ruled the airwaves at the time,” recalls Boston leader Tom Scholz. “But we stumbled onto a sound that worked, and soon everybody was imitating it.”

Article continues belowIt may have been unlikely that an album dominated by brawny riffs, harmonized guitar leads and multilayered vocal workouts would capture the imagination of America’s bell-bottomed youth. What was positively bizarre was the source of this blockbuster.

Scholz was hardly your typical rock-star-in-waiting; then 29, he was a gangly project manager for Polaroid, with a Master’s degree from M.I.T. in engineering, who spent his off hours writing and recording in his basement.

“I was basically a dork that hit the books and liked to build things and did all of the things that you weren’t supposed to do to be popular,” he says. “But somehow I ended up onstage, playing guitar in front of everybody else.”

It’s likely this very dorkiness – along with the fact that Boston vocalist Brad Delp had a throat of gold and a staggering range – that engendered Boston’s success. For who but a died-in-the-wool braniac could compose, arrange, record and perform most of the guitar, keyboard and bass parts on an album – in his basement no less – and produce such powerful results?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Even 30 years after its original release, Boston is still widely regarded as one of the best-sounding rock albums of all time, and when tracks like More Than a Feeling and Rock & Roll Band come on the radio, few can resist indulging in fits of fleet-fingered air guitar and a spirited falsetto sing-along. And now, according to Scholz, the album, along with it’s most-solid follow up, Don’t Look Back, sound even better, as they were painstakingly remastered by the guitarist himself for a new set of deluxe reissues.

Guitar World recently caught up with Scholz – in his home studio, of course – and quizzed him about the painstaking process of both making and improving upon Boston, as well as the sometimes-painful situations that the album’s massive success created for a band that, for all intents and purposes, never expected their work to see the light of day.

Were there specific things about Boston and Don’t Look Back that you wanted to address when you remastered them?

"There were always things that I wished could have been louder or quieter, but what bothered me the most was what happened when that nice analog audio was converted to 16-bit digital for CD.

"After that, I couldn’t listen to either one of those albums anymore, and I literally did not listen to either one in the past 10 years because you could only hear them on CD. I thought they sounded terrible – screechy, irritating and, well, you know what 16-bit can do to sibilance."

Did you do any remixing at all to readjust the levels that had been bothering you?

"I had to pass on the possibility of actually remixing for several reasons. First of all, the tapes were too old to play more than a couple of times, and I refused to transfer to digital and then remix. Also, those mixes are what people identify with the music that they love, whether they heard it for the first time five years ago or 30 years ago.

"But what I did want to do was bring out all of the things that were buried in there, undo all the damage that was done from the digital conversions and correct a lot of minor problems.

"We got virgin 24-bit files run off from the master two-track tapes, and me and my digital editing engineer, Bill Ryan, got to work. I know everything that you can do with digital processing and digital editing inside and out, but I absolutely refuse to push the buttons and don’t even want to know how to load and unload the files."

Do you hate computers in general, or specifically as devices for working on music?

"I detest computers. If you had a device like that 30 years ago that froze up constantly, misbehaved constantly, lost your information and screwed up when you needed it the most, it would have been laughable.

"I, for one, just don’t want any part of it, so my solution to being able to utilize the abilities of the computer without having to be harassed by its abysmal performance is to get somebody else to run it. And you really need that, because any microprocessor-controlled device is so damned complicated that it requires a major part of your brain just to operate it.

"So you get one person who pushes the buttons and somebody else who’s got the overview of what you’re trying to do."

Did you spend quite a bit of time doing the remastering?

"Bill and I took this on as sort of a personal challenge. We said, 'We’re only going to use the two-track, and we have to fix all of the mix inadequacies from having done it 30 years ago without automation and correct all the problems that resulted from the 16-bit A/D conversion.' And we just started at the beginning, and literally, fraction of a second by fraction of a second, went through the whole thing.

"We made very precise changes to a vocal line, a word, a crash cymbal, short guitar leads and power chords, the beginning of a snare hit, the tail end of a snare hit and so on.

I couldn’t work in a studio with people milling around and some engineer that I had to wait for to rewind the tape. I did it all myself, very quickly

"By now I know the frequency content of virtually any sound that’s in a Boston production, so when Brad sings, I know where it is, and if he’s singing a certain vowel sound and there’s a problem with the tone of it, I know where it is, and I know what to change and how long to change it. And because I also know what’s in the background or foreground while something’s going on, I know what I can and can’t do."

Did going through the songs in such minute detail bring back a lot of memories?

"I remembered playing all of those parts. They were all recorded in the basement of my apartment on long nights, and it was a bit of a grind. Our record label, Epic, didn’t want to use the demos they had signed us from, but they wanted a studio version exactly like the demo.

"Now, the only way that could be possibly done was if I played those parts just like I did on the demo, and I could not work in a production studio. I worked alone, and that was it; I had been doing it for years and years, and I had adapted to it. I couldn’t work in a studio with people milling around and some engineer that I had to wait for to rewind the tape. I did it all myself, very quickly.

"So I took a leave of absence from my Polaroid job – I was gone for several months – and I would wake up every day and go downstairs and start playing. It was a little bit annoying, because I was basically reproducing the same exact parts that I had played on the demo, and I don’t usually do that.

"What you hear on most Boston albums, the licks I play, that is the first time it ever happened. But in this case they wanted the same thing, so I had to replay the same parts exactly the same way with the same equipment – and in the same basement, for God’s sake!"

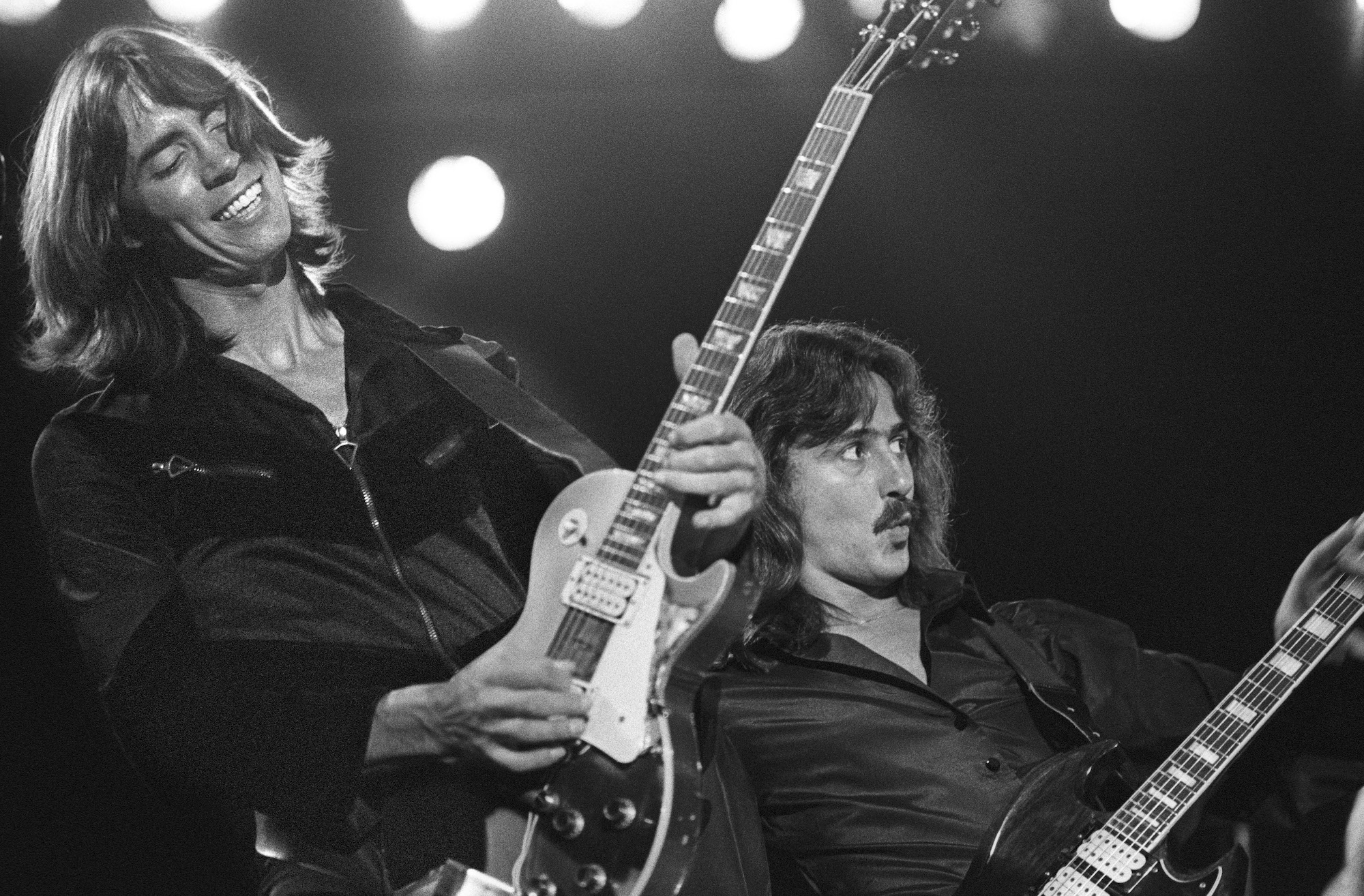

Can you describe what that basement looked like?

"It was a tiny little space next to the furnace in this hideous pine-paneled basement of my apartment house, and it flooded from time to time with God knows what. I put in some partitions, and I built a tiny isolation booth that was completely carpeted. You could just get the drums in there – just.

The drums on Boston were recorded in your basement?

"Everything was recorded in the basement. The whole thing was done in that basement on a 12-track Scully tape machine. I had a Hammond organ and a Leslie speaker stuffed in the corner where the drums were. I would tear the drums down and pull the Leslie out a little bit when it was time to record the organ parts."

You would later go on to develop the Rockman headphone amplifier, a device that also revolutionized the process of recording guitars directly into a mixing board. Were any of the guitars on Boston recorded direct?

"No. They were always done with a prototype of my Power Soak power attenuator, at low volume, through a standard cabinet close-miked with an Electro-Voice RE16.

"I was using mostly a Marshall head that sounded like doo-doo on its own, but with a Crybaby wah pedal, an EQ and these old Maestro Echoplex tape delays in front of it, it sounded really good. It was noisy as hell, so I’m sure that I was getting some preclipping before it got to the head. For guitars, I had two Gold Top Les Pauls that both sounded very similar, and that was it."

Boston presaged modern recording, in which many artists make hugely successful albums in their home studios.

"You know, when I got out to L.A. where the record was going to be mixed, I was a little intimidated because I figured that these guys knew everything and I was just this hick who worked in a basement. But they were so backwards.

"They did not know how to spot erase, they did not know how to punch in and out to get in for quick fixes on things – they didn’t know how to do any of this stuff that I was doing all the time. These people were so swept up in how cool they were and how important it is was to have all this high-priced crap that they couldn’t see the forest for the trees."

At the time of the first album’s release, critics accused the band of creating the “corporate rock” sound.

"It was a travesty, I tell you. [laughs] Basically, Jim [Masdea, Boston's drummer], Brad and I were just music lovers who were experimenting in the basement. I certainly had no thoughts and entertained no hope of anybody ever paying 10 seconds worth of attention to what I was doing.

"I was doing it because I liked it, and I thought, Well, maybe there’s a group of people out there who would like this, too. I had always simply entertained hope that I would get some sort of a little break and be able to perform. I mean, I was thinking clubs around town! And in the quest to get there, I basically became an experimenter in the basement, and you don’t write and record pieces like Foreplay because you think this is going to be the formula for a hit song!

"What we did do, however, by my experimenting with arranging and writing and Brad with his harmonies, was stumble onto the pop rock success in the Seventies that everybody thought was impossible because disco owned the airwaves. And we stumbled onto it, and then after that, everybody was trying to imitate it."

Still, beyond simply experimenting for the pleasure of it, weren’t you also sending demo tapes out to the record labels?

"Yes, and they were totally rejected – and nastily, too! The rejection that we got from Epic, from the A&R guy who later, incidentally, credited himself with discovering Boston, was something scathing like, 'This band has absolutely nothing new to offer.' So not only did I not think that we were onto the formula for corporate success but the corporations hated us!! [laughs] So it’s quite ironic.

"I think that part of the reason we got slapped with that nasty label is that the writers – the ones who gave us that label – hated our guts. They didn’t review us and say that we were up and coming; we didn’t get written up in the local press where they could say, 'Watch for this band'.

"We happened before they even knew that we happened. And I think that really irritated some people, because they felt that they were the gatekeepers and we had passed right through it. You do that and people are going to get mad."

By all accounts, the making of Don’t Look Back was significantly more harrowing than that of the first album.

"They were trying to squeeze it out of me like the last bit of decorating frosting out of a paper tube."

How much of a time crunch was it?

"It was awful. I was trying to do my usual thing – going into the studio and experimenting – and all of a sudden I’ve got all of these people on my case. 'Well, how much longer is it going to take?' And, 'Well, how many songs do you have done?' And I went, 'Wait a minute! The band you wanted was the one that did its thing in the basement!' And basically the thing got pulled out of my hands before it was done.

"I needed another song; it’s ridiculously short. It’s absurd for a CD, but it was even ridiculously short for a vinyl album. I also would have gone back and remixed a few of the cuts."

When you were making that record, were you sitting there thinking, Oh my God. What did I get myself into with this?

"Well, it was a lot of fun. I mean people pay attention to you all of a sudden, so I didn’t want that to stop, and I’d spent every cent I could make and all of my time getting myself to that point. I never expected it would be that successful, but I wasn’t about to let that slip away easily, so I worked very hard on it. But there was only so hard I could work."

It sounds like the kind of high-pressure situation that has blown many a successful musician’s mind.

"An awful lot of stuff happened, and unfortunately, I didn’t know much about human nature at that point, even though I had turned 30 and worked in the industry quite a bit. But, boy, did I learn a lot about human nature! And not good things. It was awful, and the shady, nasty side of the human population that I saw come out was very disconcerting.

"I was also absolutely surrounded by drugs; it was everywhere. Drugs ran everybody’s life, and I didn’t know anything about it. And I stupidly allowed myself to get around these people because I wasn’t aware of how dangerous it could really be to be around people like that.

"You know, Brad and I were really, really naïve, and even though I was highly educated and had been a senior project engineer at Polaroid and thought I was pretty capable of handling myself, I wasn’t prepared for what I ran into."

Was there part of you after the first tour that was like, “Wow I don’t even want to go back out there again”?

"Things really got to that point during the recording of the second album, and then during the second tour I realized that I could not be around these people anymore. Apparently Brad had already reached that point, because he said he wasn’t going to go on tour again after that. And my initial reaction was, 'Well, shoot, I’ll have to find some other singer.' And then I thought, Wait a minute. I don’t want to go on tour either!

"So that part of it was all bad. But the albums themselves and the music – listening to those songs doesn’t remind me of all the bad things and of having to deal with all the other people. Because ultimately, it was a pretty personal effort."

Since 1980, Guitar World has been the ultimate resource for guitarists. Whether you want to learn the techniques employed by your guitar heroes, read about their latest projects or simply need to know which guitar is the right one to buy, Guitar World is the place to look.