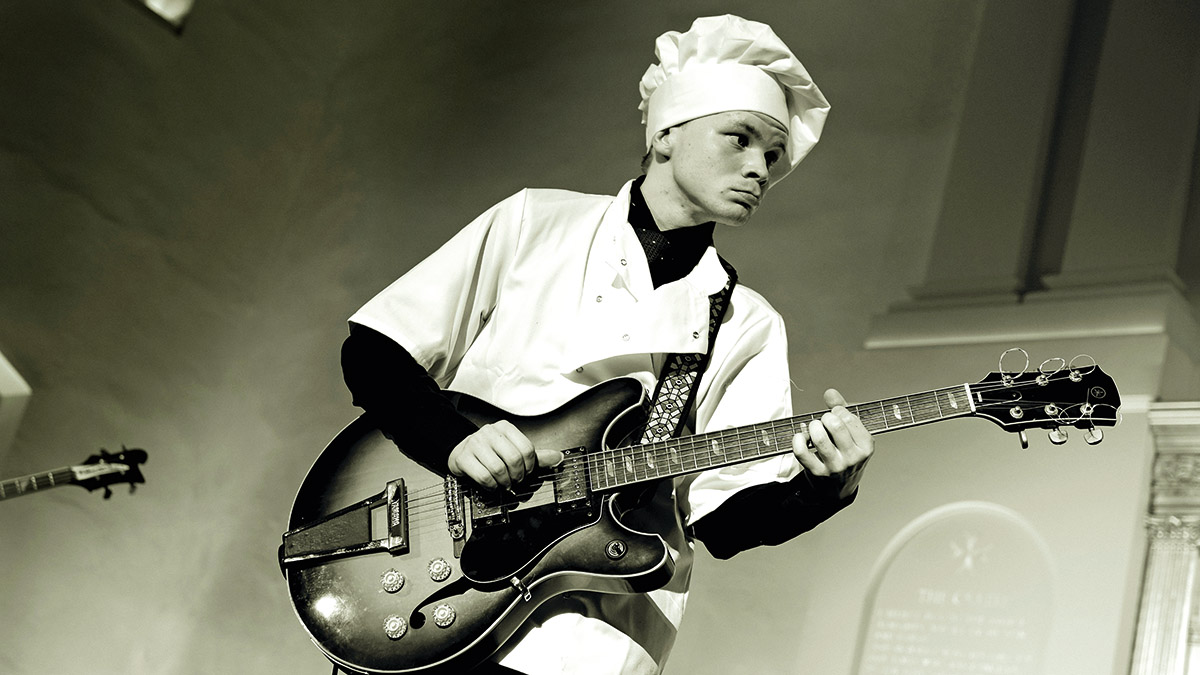

Black Midi’s Geordie Greep on how he learned to stop worrying and love his amp

Sometimes the best answers to our tone problems are right there in front of us. As Geordie Greep explains, even if you play experimental post-punk, a dimed Marshall solves everything

What can an experimental rock band learn from AC/DC? “The biggest breakthrough was in terms of amplifiers,” grins Black Midi guitarist/vocalist Geordie Greep.

While his post-punk peers wonder how to fit their vast pedalboards into the tour van, the Greep (as he is known to his friends) has rediscovered the joy of plugging straight into the amp. And it all started when Geordie decided to channel Angus Young in Black Midi’s live set – playing the intro to Riff Raff, the frenetic opening track to AC/DC’s legendary 7’0s live album If You Want Blood You’ve Got It.

“There’s not many better guitar sounds than Angus’s on If You Want Blood,” Geordie says. “I was like, ‘Forget the pedals, let’s just start turning the amp up to 10 and using the volume control on the guitar!’ After that we were like, ‘Wow, this is way better. This is the way to do it!’”

This discovery happened as Black Midi began recording their third album Hellfire. Geordie was using the rig he’d had since 2021 album Cavalcade: an Orange TH-30 run clean with pedals. That was until his fellow AC/DC fan Max ‘Sizzle’ Goulding, Black Midi’s co-producer, spotted a Marshall JMP head in the studio. Geordie was uncertain. The studio’s engineer said it wasn’t the best amp.

“Sizzle was like, ‘Look, we’re definitely using it!’” Geordie laughs. “So we got it set up with a 4x12 and just turned it up to 10 and went straight in. It sounded way better than any amp I’ve ever heard.” And that is how Black Midi became unlikely 21st century champions of the cranked vintage Marshall.

The AC/DC influence is not immediately apparent on Hellfire. The new album continues where Cavalcade left off – a daring romp through every genre they can think of.

It’s as though they’ve just discovered all the music in the world, and they love it all too much to leave any unplayed. Perhaps surprisingly, it works, held together by their sense of humour and outstanding musicianship.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Geordie’s songs often begin as pastiches. “Trying to come up with a pastiche of a waltz, a show tune, a South American song, a blues or a funk track, you throw yourself into this thing where it’s just fun,” he says.

“Along the way you think ‘What if you put in this chord which they never use, or you suddenly went into this rhythm which they don’t usually do?’ It’s just ways of taking things we know but altering them slightly. Not for the sake of it, but to make something that’s interesting and hasn’t exactly been heard before.”

Hellfire is packed with stuff we’ve never heard before, but Geordie highlights two tracks. Sugar/Tzu has a breakneck chromatic riff: “That fusion riff is really fun to play. It got steadily faster as we played it more, so now it’s at a stupid speed.”

His other favourite, Dangerous Liaisons, is inspired by Brazilian guitarists: “It’s not something you necessarily think straight away, but it has a lot of Latin chord voicings and syncopation.”

Geordie rarely writes music to be deliberately jarring, but he is keen to avoid predictability.

“I think [jazz guitarist] John Scofield said as soon as you play something that’s a lick or a physical pattern rather than a musical one or a melody, then you failed,” he recounts. “If it’s not as pure as imagining it and seeing it in the moment, it’s not music. That’s his view. I think there’s truth in that.”

Although they’re frequently joined by piano and horn players that can swell their numbers to as many as eight, Black Midi are actually a trio. Greep, drummer Morgan Simpson and bassist Cameron Picton write their songs individually, sharing demos with each other.

“Then when we come together we work out what arrangement-wise is the best option for the group,” Geordie explains, “We’re taking leads from those demos but often also putting in new touches. We each play quite a lot of instruments, so even the demos are usually already quite multi-layered and symphonic or whatever, and then we come together and see what we can replicate and what we can add.”

With the guitar you end up relying a little bit more on physical patterns and shapes. It’s much easier to get trapped into just playing the same things

Black Midi are one of a handful of cutting-edge acts that are still thoroughly guitar-based, and Geordie admits the guitar has limitations.

“One thing that’s challenging about the guitar is the fact that you don’t choose what inversions you’re playing,” he says. “On the piano you have exact control over what notes to play. The melody can always come first because you can see it there and fit the chords around it.

“With the guitar you end up relying a little bit more on physical patterns and shapes. It’s much easier to get trapped into just playing the same things. You are quite inhibited with what you can play.”

To get around this problem, Geordie often starts from the melody. “I create chords from scratch around that,“ he explains.

“I’m not pretending I’m inventing chords or anything, but I’m not necessarily sure what that chord is called. I sometimes use passing chords for almost every quaver rather than fitting the melody around stock chords. Just tailor the chords to the melody rather than the other way around. I think that’s a much more musical way of working.”

If using a different chord for each melody note reminds you of J.S. Bach, that isn’t entirely coincidental.

“I think the most perfect piece of music is probably Bach’s Mass in B Minor,” Geordie says. “I never had a classical education, but I think the idea of melody coming first and fitting everything around that is what’s so compelling about that music. Every part in the score is as complete as the full score.

“Every line has independence. Every time you listen to it there’s something else you can listen to. I don’t think anyone’s music will reach those heights in the next hundred years, but it’s a good guiding light to aspire to.”

Black Midi have the distinction of sounding genuinely unlike anyone else, and Greep’s process for creating is surprisingly grounded. “The main philosophy really is instead of relying on divine inspiration or whatever, to instead just work hard and keep working every day,” he says. “That’s the only way that you can reliably come up with good things – just doing it every day without fail.”

He admits there are days where he struggles to write: “But if you do it every day, the instances of that are less and less and the instances of inspiration seeming to come from nowhere happen more and more frequently. I always think if a boxer is asking ‘How do I get better at boxing?’ you don’t say ‘Wait for inspiration,’ you say, ‘Go to the gym.’”

We like to retain a little bit of tension for a recording studio, because oftentimes the best stuff is when it’s on the verge of collapse

In the studio, Black Midi don’t waste any time. “We usually do just one or two rehearsals and then go straight to recording,” he says. “We don’t like spending too much time getting the songs so tight that we can play them asleep. We like to retain a little bit of tension for a recording studio, because oftentimes the best stuff is when it’s on the verge of collapse.”

They record live as much as possible, but for Hellfire they found some songs had to be multitracked. “There were a few songs where we thought it was important it stays that specific tempo. There’s a few times where we have recorded stuff live and then you listen to it back and it’s just way too fast. I don’t think those tracks recorded with a click particularly suffered from that, but the stuff that needed to be live was recorded live.”

This minimal-preparation approach combined with live takes does result in some mistakes slipping into the final product, but Black Midi embrace those moments.

As Geordie puts it: “A lot of the time that’s the magic of it, where it’s kind of idiosyncratic, of the moment unexpected slight permutations in what you were going for but have their own sort of more spontaneous character. It’s always something that can’t be faked.”

The main guitar on the record is a late-’70s Yamaha SA-60. “It’s basically like a 335 with squared off cutaways,” he explains. “It just feels wonderful and the pickups are really quite bright for a semi-acoustic. Like a lot of that period of Japanese guitars, the neck is just wonderful. The action is incredibly low for a really old guitar but it’s an easy guitar to play. I always like having quite a big body on the guitar because you can feel the vibrations of the notes.

“A lot of the time I’ll be in the middle position between each humbucker. I don’t really mess with the tone controls. Playing on your own, doing that stuff that sounds great. As soon as you listen to it in the control room it’s like ‘Where’s the guitar gone?’ You can’t even hear it anymore.”

The SA-60 was joined by Greep’s Mexican Stratocaster and a Gibson SG Faded, but he wasn’t satisfied with either. “The Strat feels really nice to play but it doesn’t sound that great,” he says, “and the pickups are actually great in the SG but it never stays in tune.”

Since recording, he has upgraded these to a 60th Anniversary Stratocaster and a custom shop Gibson SG Les Paul. A previous owner added a Seymour Duncan humbucker (unknown model) to the Strat, which Geordie prefers: “The standard Strat pickup is great for a lot of things but for what we’re doing I always find it a bit too piercing and brittle.”

Now that Geordie has discovered the joys of a loud Marshall, he’s not going back. “For the last tour, our manager has an old Marshall Plexi amp and we had that into a 4x12,” he says. “When we can’t get hold of that now what we do is have the Orange TH-30 going straight into a 4x12. That’s not quite as good but it’s 95 per cent there. It’s odd how much difference just the speaker cabinet makes.”

Inevitably, this means Black Midi gigs are loud affairs, but Geordie is adamant it’s not his fault. “Morgan, the drummer, plays so loud everyone needs to be that loud to be heard! The Plexi’s not even as loud as the Orange. I used to have the Orange at about two or three maybe, but even that was full volume. It would just be more distorted if you turned it up.”

And then Geordie commits post-punk heresy. “The thing with the new Marshall setup that’s really good is I’m not using any pedals anymore!” he declares. “All I have is a volume pedal and an EQ, which I use as an overdrive palate. I always have my foot on the volume pedal and control the gain that way. It’s much more rewarding.

“You feel like you’re driving a sports car or something! Every little movement you get a bit more or a bit less of the growl of the amp. It’s not on-off – not like ‘here’s distortion, here’s no distortion’ – but every bit of the song you can change it slightly to get a little more or a little less. It’s just been excellent.”

Whatever kind of music you’re making, it’s the melodies and the chords that shine through

The EQ is an ’80s Boss GE-7B Bass Equalizer, made in Japan, which Geordie uses to boost the amp. Divulging a trade secret, he reveals, “I often turn up one of the lower bands to full and one of the high bands to full and then you get like a total Frank Zappa-like a wah sound.”

For all Black Midi’s experimentalism, Geordie has solidly traditional advice on what makes a song great: “Whatever kind of music you’re making, it’s the melodies and the chords that shine through. Sonics can be a hook, but any music you truly love is going to be because of those elements.”

- Hellfire is out now via Rough Trade.

Jenna writes for Total Guitar and Guitar World, and is the former classic rock columnist for Guitar Techniques. She studied with Guthrie Govan at BIMM, and has taught guitar for 15 years. She's toured in 10 countries and played on a Top 10 album (in Sweden).