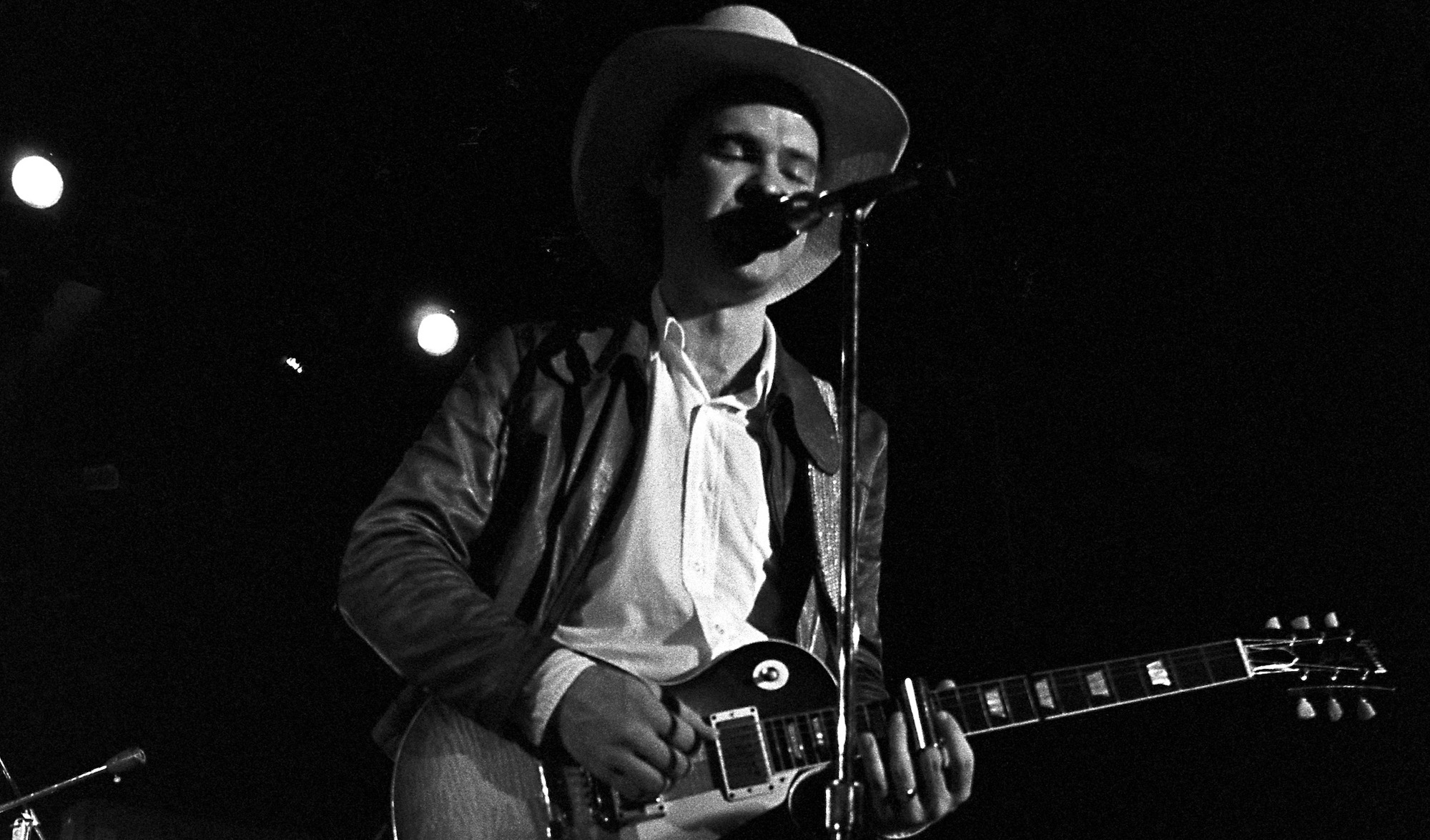

“It was considered a no-no to chain two Fuzz-Tones together. But I saw Hendrix chain five of them!” Billy Gibbons remembers opening for Jimi Hendrix with his pre-ZZ Top band the Moving Sidewalks

Before the long beards, sold-out arenas, spinning fur guitars and MTV stardom, Billy Gibbons cut his teeth in a psychedelic group called the Moving Sidewalks, who opened for – among other A-tier rock acts – one James Marshall Hendrix...

Billy Gibbons is best-known, for good reason, as the electric guitar icon who brought Texas barrelhouse blues – with long beards, catchy hooks, and some of the zaniest guitars west of the Mississippi on the side – to the mainstream with ZZ Top.

Before the MTV stardom, before the radio hits, and even before the Little Ol' Band From Texas existed, however, Billy Gibbons was already a hot commodity in rock, leading a blues-influenced psychedelic combo called the Moving Sidewalks.

Though they never broke through nationally, the band's most well-known tune – the seminal 99th Floor – was a huge hit in the Houston, Texas area in 1967, and secured the Moving Sidewalks opening slots for some of the biggest rock stars of the day, including the Doors and one James Marshall Hendrix.

As he did with so many other guitar players, Hendrix in particular left a significant impression on Gibbons. Though their respective spins on the blues they grew up on were worlds away from one another, Hendrix's sheer fearlessness on the guitar stayed with Gibbons the most.

“It was unspoken but quite evident that Hendrix threw caution to the winds, and decided to do things to and with a guitar that were not necessarily written in any of the how-to books,” Gibbons told Guitar World in a 2008 interview.

“For instance, it was considered a no-no to chain two Fuzz-Tones together,” he went on, “but I saw Hendrix chain five of them together! And he’d do this personalized dance, stomping on five different pedals, sometimes playing with all five of them on at once.

“I think it’s fair to give him the award for breaking the rules and starting to do things that no-one dared do before. That was part of his genius: a total lack of fear.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Despite the fact that the Moving Sidewalks were opening for Hendrix – and therefore privy to the unwritten rule that openers don't go too over the top, lest they upstage the headliner – Hendrix encouraged the band to embrace their penchant for onstage showmanship.

Though the band's love for pyrotechnics got them fired from their opening slot on a Doors tour, another visually loud element of their set of the time – involving a contraption that produced a phosphorescent rain shower at a strategic point in the set – met with approval from the guitar god.

“That was actually a notion from Jimi Hendrix,” Gibbons explained of the band's captivating stage presence to Guitar World in 1994. “As we accepted the opening slot, followed by the Soft Machine, on Hendrix’s 1968 tour, he recommended that we continue this entertaining sort of appearance.”

As the '60s gave way to the '70s, the Moving Sidewalks dissolved, and subsequently evolved – with a few personnel changes along the way – into ZZ Top. Hendrix's words of advice on showmanship stuck with Gibbons, though, and inspired one of the trio's other trademarks: wild custom guitars.

“I remember me and Billy drove up to Dallas, where they had a lot of pawn shops back then [the early '70s], and he spied this old Telecaster bass,” late ZZ Top bass guitar player Dusty Hill told Guitar World in 1994.

“I think we only paid 90 bucks for it – a real steal. And when we drove back, we picked up these two girls hitchhiking, and that’s how we wrote the song Precious and Grace… but that’s another story.

“Anyway, that bass was the first guitar we ever modified. When I played it, I noticed that I either had the volume knob wide open or else completely off between songs. So we took that knob off and got one of those little window cranks – like for the vent window on an older car – and put that on. If you slapped the crank, the volume went all the way on or all the way off. So I’d have to say that window crank was the start of it all.”

Jackson is an Associate Editor at GuitarWorld.com. He’s been writing and editing stories about new gear, technique and guitar-driven music both old and new since 2014, and has also written extensively on the same topics for Guitar Player. Elsewhere, his album reviews and essays have appeared in Louder and Unrecorded. Though open to music of all kinds, his greatest love has always been indie, and everything that falls under its massive umbrella. To that end, you can find him on Twitter crowing about whatever great new guitar band you need to drop everything to hear right now.