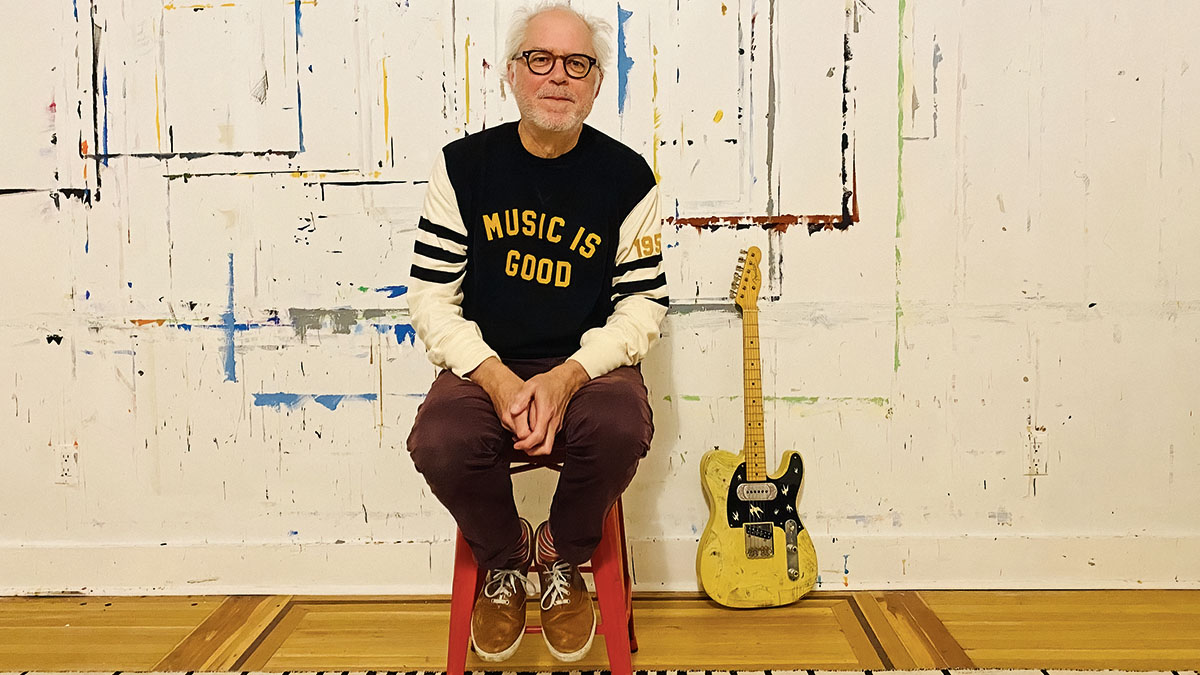

Bill Frisell: “The limitations of the guitar invite their own solutions… so there are a lot of different ways people end up playing it”

Guitarist, composer and esotericist Bill Frisell is difficult to pin down to any one musical style. Even he learned something about himself in his new biography Beautiful Dreamer

“There were things in there I didn’t even know about, myself,” Bill Frisell jokes when we say how much we enjoyed reading our advance copy of Beautiful Dreamer.

Despite his work with artists as diverse as Ginger Baker, Suzanne Vega, Brian Eno and Loudon Wainwright III, many would describe Frisell as a jazz guitarist. But, as the new book reveals, this would be a mere thumbnail sketch of a man whose work as a composer and performer spans a far wider musical terrain.

In fact, he has been described in some quarters as ‘the Clark Kent of the guitar’. We decided it was time to talk to the man himself and our conversation began with the recent tome…

How much of a peculiar experience was it to have your life and career examined in such detail?

“I spent a lot of time with Philip [Watson, the biography’s author], but I had no idea, until I finally saw it, what he was actually doing or how it would come out. He was very careful about making sure everything was accurate.

“I had to read the whole thing from beginning to end to make sure there were no obvious mistakes, so it was wild. It’s hard to describe what it felt like, going through my whole life like that, just emotional and strange. Also, I’m not that fast a reader, so, oh my God, 700 pages…”

Going back to the beginning, which childhood musical experiences left the deepest impressions on you?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I can’t remember exactly how old I was when I got a little transistor radio. I think that’s where I remember hearing music and being so enthralled. This is before I played an instrument or anything. It was just this sound that was calling out to me. I would be listening to it all the time, and have it under my pillow when I was sleeping at night and all that.

Jim Hall was coming from the inside of the music out. Everything he played was in service to the whole musical situation

“When I was in the fourth grade, when they started the music programme in the public schools, that’s when I actually picked up an instrument and started trying to mess around with trying to make some sound myself. I was taking music lessons playing the clarinet.

“Then electric guitars were coming out, like Fender guitars in all these crazy colours. I remember looking at album covers of all these surf bands and thinking, ‘Wow, look at those guitars. They look so cool.’ That’s when I started wanting to get a guitar.”

Did the early grounding in the clarinet give you a perspective on music that you carried forward to playing guitar or was it just a stepping stone?

“I had this very strict teacher. You had to tap your foot this way and follow all these rules – almost military training.

“I played in marching bands and band orchestras, but just playing with other people, you’re hearing this whole sound happening around you. You’re trying to blend in with it and play at the right volume, and play in tune, and put things in the right place – all these basic things are huge.

“Later on, as I got better, I would play in smaller chamber groups, like a woodwind quintet or something. There, you’re super-sensitive about the intonation, and how loud you’re playing, and just being in harmony with the other instruments and making a blend all together.

“That kind of stuff has really stuck with me to this day. I can remember it, and also playing a wind instrument, where you’re breathing into it, you play a phrase and it lasts as long as you can breathe.

“There’s a whole element of how the breath is related to the musical statement that you’re making, so I can feel that when I’m playing guitar now, even though I’m not, technically, blowing air into the thing, I am still breathing with what I’m playing.”

What kind of things did you learn from Jim Hall and the other jazz guitarists of the 60s?

“With Jim, it was the timing, the space, the rhythm and the way he was interacting with the groups that he played in. He was really coming from the inside of the music out. It wasn’t about him trying to show you something, show off about something that he knew or playing something fancy.

“Everything he played was in service to the whole musical situation. I think that’s what inspired me the most. The groups, like him playing with Sonny Rollins or him playing with Art Farmer, or those duets with Ron Carter or with Bill Evans, or any situation he was in, he lifted the whole thing up but from the inside out.

“Before Jim Hall, I heard Wes Montgomery for the first time, and that was the big ‘Eureka!’ moment for me. Prior to Wes Montgomery, I hadn’t really heard much.”

Both Hendrix and SRV stated they were fans of Wes – he seemed to reach across musical boundaries…

“Wes Montgomery was playing music that was popular at that moment. It was like he was the Pied Piper or something. He was like, ‘Listen to this, but look where it’s possible to take it…’ Also his connection with blues.

“Right at the heart of all this music, blues was in there. It’d be so down-to-earth, but then he would show you this way up into outer space. He’d take you from down here on the ground and go as far as your imagination could go.

“Also my age when I heard him – I guess I was 16 years old – it was just the right time in my life and where I was at with my understanding of music and what I was trying to do. The timing couldn’t have been more perfect. It led me to wanting to find a guitar teacher. I’d been trying to figure it out on my own, mostly.

“I had a couple of teachers, or I would learn from my friends or whatever, but that was the moment when I thought, ‘I’ve got to get a serious teacher and try to figure out what’s going on with this music.’

“This is in Denver, Colorado, which is not exactly the jazz capital of the world, but I was lucky to find my teacher there, Dale Bruning. He was the guy who introduced me to Jim’s music and introduced me to Jim in person, too.”

On to a broader question – what do you take to be the purpose of what people think of as jazz guitar, certainly in its classical period of the 50s, 60s and 70s?

“Oh, man. It is broad, because when you say ‘jazz,’ it means so many things to so many people. Some of the greatest jazz musicians reject the word itself, like Duke Ellington. For me, when I think of jazz, it’s like, ‘This is a place where anything is possible.’ For me, it’s music you can’t pin down.

“Okay, you could say there’s Howard Roberts, or Jim Hall, or Wes Montgomery, or Kenny Burrell, or Joe Pass, or John McLaughlin, or Derek Bailey, Jimmy Raney and Grant Green… it goes on, and on, and on.

“To me, when I hear all those names, it’s like I hear a sound in my head. It’s not just one thing. Each one of them is a complete, unique world unto themselves. I can’t think of any other instrument that has such an extreme range of expression. It’s pretty wild, right?”

The guitar is an idiosyncratic instrument. What do you regard as its best qualities and its worst?

“There are limitations. On a piano, everything is laid out in front of you. Visually, you see the whole thing. On the guitar, there’s a lot of deciphering that you have to go through. You have to figure out where things are, and you can play the same note in different places.

When I played the clarinet, basically you push this button down and it makes that note. That’s where you play that note. On the guitar, it’s a bit more mysterious

“When I played the clarinet, basically you push this button down and it makes that note. That’s where you play that note. On the guitar, it’s a bit more mysterious. You can play an A – an open A – or you can play an A on the E string, or you can play it on a different string. It’s scattered around. Just the way it’s organised is quite a bit different than some other instruments, so you have to sort all that out.

“I think, whatever the limitations are, they push you into finding ways around them. So there’s a lot of opportunity for different people to find their own way. I never really thought about it quite like this, but maybe the limitations of the guitar invite their own solutions. There are a lot of different ways to get to those solutions, so there are a lot of different ways people end up playing it, I guess.”

In your career, you’ve played many makes and styles of guitar. What do you look for in a guitar these days?

“Oh, boy, that’s just never-ending. I have a lot of guitars and if I get another guitar, there’ll be something – it could be a subtle thing, like the way the overtones ring – that leads your fingers into some other place, or leads your ear, pulls you in a certain way. It’s like each guitar will tell you something, it’s like a teacher.

“Then when you go back to another guitar that you were playing before, you’ll realise there was something in there that you didn’t know was there before. If I play an acoustic guitar for a long time and then go to my electric guitar, it’ll show me things on the electric guitar I hadn’t thought of before.”

You’ve made this wonderful virtue of eclecticism in your music. What are the challenges of being broad-ranging in one’s playing, as opposed to purist?

“To me, that shows I love music and I don’t want to be hemmed in, in any way. I’m just following what I love and it’s never-ending. It’s like, ‘Wow, how am I going to do this?’ That’s the challenge all the time. You go chasing after it and try to understand it. It’s not consciously trying to be eclectic or anything. It’s just that I like music and I’m trying to figure it out.”

We guess sometimes it can be easy to forget you’re there just to create, really…

“When I was first in a band, we were in one of these ‘Battle of the Band’ contests. People were saying, ‘You have to move around more. You need to dance around.’ I was just standing there playing. In my mind, the music was dancing around, but they wanted me to move my body. I never felt comfortable with all that stuff.”

The biography is the reason we are speaking, but what, more broadly, are you up to musically at the moment?

“There’s a lot of going on right now. I just finished recording a new album a couple of weeks ago. I’ll be mixing that in a couple of days, and then I’m travelling to San Francisco to play with Ambrose Akinmusire.

“Then I go to England for the release of the book. I’m going to play one solo concert there [in London’s Jazz Cafe in November]. It’s just one thing after another. It’s crazy. Then I go to Germany to play with John Zorn, and then come back to the States. I’m traveling pretty much non-stop these days.”

- Beautiful Dreamer: The Guitarist Who Changed The Sound Of American Music is out now via Faber & Faber.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)