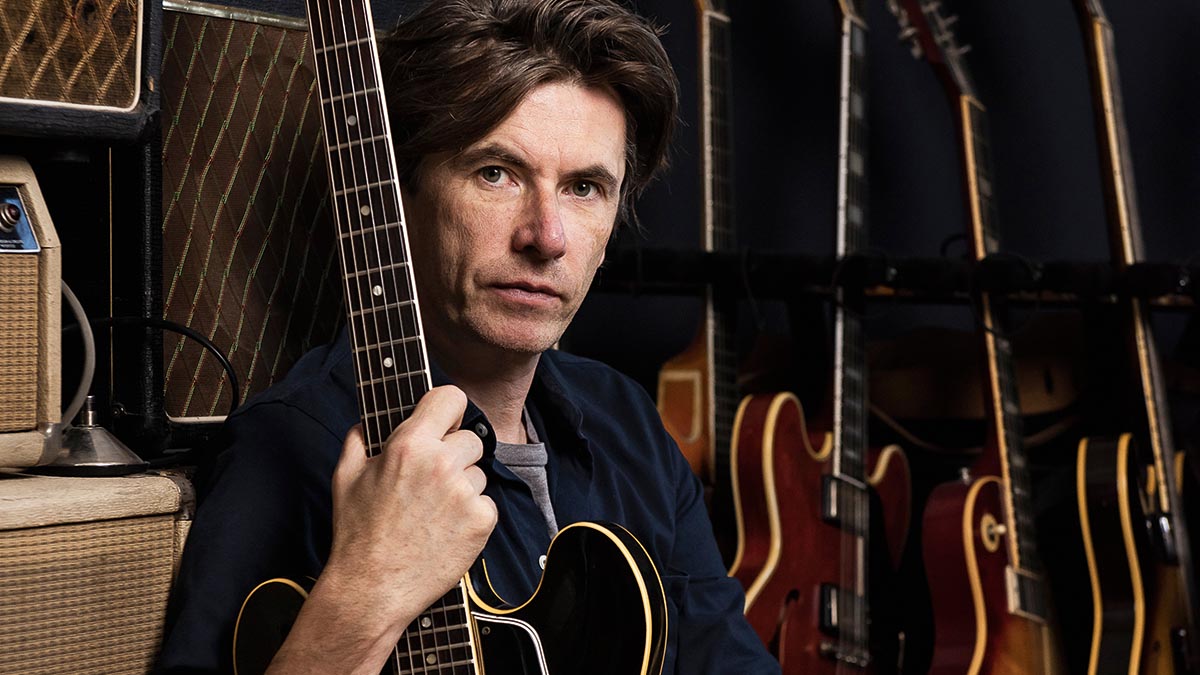

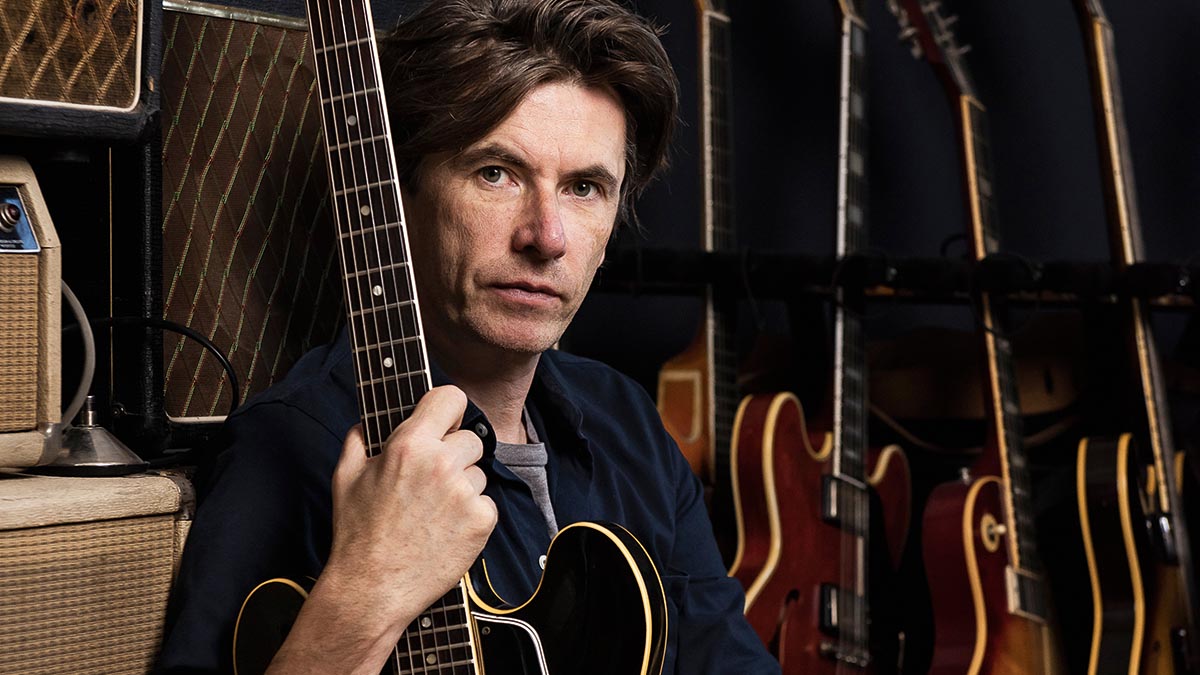

Bernard Butler: “The best thing about a Tele is that when you bash them, they look even better. You don’t say that about the 355!”

As the Brit-rock guitarist releases a reimagined take on his 1998 solo debut, People Move On, he revisits the no-expenses-spared sessions, the vintage guitars and the ambition in the air

The late '90s were a tumultuous time for Bernard Butler. By 1998, the guitarist was four years out of Suede, the band that made his name, while a partnership with the mellifluous vocalist David McAlmont had broken down in similarly acrimonious style.

Yet Butler was finding his voice, in every sense, not only starting to sing but discovering artists such as Bert Jansch and broadening his scope beyond the glam-inspired crunch of old. And when Creation Records offered him one of the music industry’s last blank cheques to chase down his first solo album, People Move On, Butler turned in what he now calls “a flawed, majestic trainwreck, overwrought and overdone”.

Butler’s solo career didn’t last, and while the guitarist has gone on to become a fascinating, diverse and highly successful figure – involved with everything from playing guitar with Robert Plant to producing The Libertines – you sense the missed opportunities of the era have always rankled.

As such, and despite his hatred of nostalgia, this year, almost a quarter-century later, Butler has re-examined People Move On to see what he could add to the youthful document by applying the perspective of a seasoned 51-year-old musician.

Set for release at the end of January, this People Move On: 2021 Special Edition is a long way from the lightly buffed reissues that merely repackage dog-eared material for die-hard fans. To his credit, Butler has swung a wrecking ball through his own work, resinging the vocals from scratch and adding new guitar parts on impulse.

No wonder, then, when we meet him at his home after the process, the guitarist seems like a weight has lifted – he has finally able to present this album as it might have been.

What made you want to look again at People Move On?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“The Demon label had asked me to do the reissue for a while. And I had said no. I mean, reissues take a long time. You do have to devote a lot of time to it. Some artists don’t make any effort at all, and that’s a bit rubbish. But, for me, I tend to work on my own, so I knew it’d be quite time-consuming. The other reason was, I just had a bit of a glimmer of not loving it, not wanting to go back. There were too many flaws for me to commit to it.

I felt at the back of my mind it was a lingering disappointment, something I dropped the ball with and just went off and tried to forget about it

“What changed that situation was that, over the last couple of years, I’ve gradually got back to performing on my own and writing on my own, which I just didn’t do for a good 15 years. I’d been producing, writing with other people, spreading myself all over the place. And I just didn’t go back to it. But it was something I wanted to address because I felt at the back of my mind it was a lingering disappointment, something I dropped the ball with and just went off and tried to forget about it.”

How did the process start taking shape?

“I started going to a rehearsal room, just on my own, with one guitar, and playing the songs. I didn’t want to go back and listen to the records, write down chords and lyrics. That was just too much like hard work. I thought it would be more interesting to just try and remember the songs.

I really enjoyed the process, performing songs that I haven’t performed for years, thinking, ‘That line was a bit s**t when I did it. Let’s fix that’

“You might forget a chord shape or change, or you’d get the key wrong, but it didn’t matter because you were trying to find that pure element that represented the song. If I couldn’t remember the lyrics, I’d make them up. If I couldn’t remember chord changes then I didn’t really care.

“So I did this on my own, completely. I didn’t tell anybody I was doing it for about six months. And I really enjoyed the process, performing songs that I haven’t performed for years, thinking, ‘That line was a bit shit when I did it. Let’s fix that.’

“A great part of this was rediscovering my voice, as a 51-year-old man, rather than a man in his 20s. And just giving myself that time, to stand in a rehearsal room, make some noise, sing my heart out and play the songs from memory, for nobody except myself. Then Demon came back, and I said, ‘You know what? I’ve got an idea.’”

At the end of the process, what was your impression of what you’d done then versus what you’ve done now?

“As human beings, you expect a certain amount of humility, I think. But when it comes to music, fans are shocked when you say about your own work, ‘I don’t think that’s very good,’ because they’ve invested in it. But, for me, I can happily say that now. Just being self-critical in healthy way.

“These days, we’re living in an ‘awesome’ world, aren’t we? Everyone’s got to be absolutely extraordinary and having a brilliant time and looking fantastic, all the time. That’s a worrying thing. I’m happy to say I think a song I did is just ‘all right’.”

I think there are some good songs on this record, but, essentially, the biggest problem is I didn’t think about how to deliver them vocally

Let’s talk about the original recording and your approach on guitar. What was the mood when you went into the studio for People Move On?

“Well, I was given an opportunity to do anything. Carte blanche. This was the '90s, so it will never happen again. Creation Records, who were running everything at that time, with Oasis et cetera, became interested. They threw themselves behind me and said, ‘We just want you to make a record.’

“I went into RAK Studios in London and I’d stay there for about a month having a brilliant time. We ended up going off to AIR Studios to mix it, and we did the strings there, too. And no-one worried about the money at all, and I could do what I wanted.

“There was an outpouring ready and I think that’s reflected on People Move On. I think there are some good songs on this record, but, essentially, the biggest problem is I didn’t think about how to deliver them vocally. And so I delivered the vocals in a slightly affected way. Which now I don’t like. The vocals are okay. It doesn’t kill me. But that was why, going back to the album, it was the first thing I wanted to do, and to recover from.”

You Light The Fire was a wonderful moment of acoustic fingerstyle. What was the inspiration?

“Well, it was clearly Bert Jansch. I had discovered him a little bit before, the classic first couple of albums. And, of course, there was Nick Drake and that era of fingerpickers. I didn’t really understand a lot about it.

“I didn’t get into learning Bert’s songs or tunings, but I remember just hearing what he was doing and loving certain inflections. And I’d say that You Light The Fire – which I played on a 1971 Martin D-28 – was a starting point. I guess it’s a first attempt at getting into that territory. It was definitely from discovering Bert.”

And you went on to become friends and collaborators, of course…

“I met him in about 1999. We just started hanging out. He had a flat in Kilburn, we became friends, and I played on a couple of records from that period and we did a lot of gigs together. A massive inspiration in my life. Not just as a player but as a human being. The way he presented himself. His humility and dignity. His absolute devotion to the pure essence of creativity and music.

Bert Jansch wasn’t the old rocker down the pub who wanted to go on about the old days. You’d just go round and he’d say, ‘D’you want a cup of tea?’ Then you’d sit down and he’d just start playing

“Bert never spoke about influences, really. I very rarely saw him put on a record. And even though you could have grilled him – about Dylan or Paul Simon, or all the greats who were around him and clearly watching him – you just didn’t do it. He wasn’t that guy. He wasn’t the old rocker down the pub who wanted to go on about the old days. You’d just go round and he’d say, ‘D’you want a cup of tea?’ Then you’d sit down and he’d just start playing.

“I never really got him to show me how to play stuff. I didn’t really feel like I wanted to get into doing ‘guitar lessons with Bert’. It just wouldn’t be the most creative thing, getting him to show me Angie or something. I just thought, ‘What can I add to this?’ And so I’d see these things that he did – or at least I thought he was doing – and try to adapt them.”

What electric guitars were you using on the original People Move On?

“The 355 would have been the main thing. It’s a ’61 355 and that’s been my guitar since 1993. It’s still the guitar I use 90 per cent of the time. It’s a bit of a luxury to have as your everyday guitar, but it’s become part of me and the way I play. It’s that old pair of boots that you get to know.

“When I was still in Suede, I had a 345, and our van was cleared out overnight in Toronto. So we were moving down the West Coast, and by the time we got to LA, I went to the Guitar Center on Sunset, just went in and bought this 355.

“It was $4,500. Which at the time, I thought was an extraordinary amount of money, but I was also young and on tour in America. You know, ‘Whatever! Let’s get a tattoo!’ It’s probably worth insane amounts now. In that era, you could still buy guitars for relatively sane prices. I couldn’t now. So this is the main guitar, and it was on the second Suede record and everything after that.”

Which other models were in the mix on People Move On?

“There’s Johnny Marr’s 335 12. That’s on this record quite a lot. The acoustics would have been this early '70s Martin D-35 12, which is the sound of the song Stay, with the D-28 for all the fingerpicking. Then there’s this 1960 330 with P-90s. I got it around the time I was making People Move On.

“There was a tiny guitar shop underneath the Chelsea Hotel. I remember walking in, and it was one of those classic ‘I’ve got something for you, mate’ moments. The guy went out the back and brought this guitar out. This is a custom black. I use it an awful lot. It’s as light as a feather.

“I tend to use it for the mellow tones, on the neck pickup. So this would have been on the song People Move On where there’s an electric solo. I later found out that there were only five of these made in 1960. And apparently Keith Richards has two of them.”

What can you tell us about the Tele we shot today?

“It’s heavy and it’s a beast, and if you drop it, it makes it even better. That’s the best thing about a Tele – when you bash them, they look even better. And you don’t say that about the 355. So I used this Tele quite a lot.

“There’s a song called Autograph, which has an intro riff and that would have been this guitar. This was bought around the same time as I bought the 355, and I really love this guitar. Again, I think it’s an early '70s model with a Fender Bigsby. A beautiful-sounding guitar.

“So it was easy to split the album between the fat humbucker stuff and then the wiry Telecaster. In my head, I would’ve chosen things in that way. Y’know, if I want a wiry riff sound, I go for the Tele. And then as soon as I want the creamier, fatter fuzz, I’d be going for the 355.”

Were you working with different guitar amps on that record, as well?

“There’s this Fender Tremolux behind me – I use this quite a lot – and the AC30 at the time. Those would have been the main things. I’ve got a Hiwatt 100, which I used quite a lot on that album, actually, with the AC30 and Fender.

“Again, it would probably be split between – you want that thinner sort of feel, you go for the Fender, and as soon as you want to turn stuff up, you go for the Vox, make it scream.

“The Lazy J is the thing I use all the time at the moment. I’ve got a Vox AC4, and a little Gibson Skylark, which I think was probably on this record. Y’know, getting past that idea that volume means bigger – because often, in the studio, it doesn’t.”

You’ve laid the ghost of People Move On. So what’s next for you?

“Funnily enough, I’ve got a record with another artist, which I’m not really allowed to talk about just at the moment, but I’m really proud of it. It’s my DADGAD album. I sunk into DADGAD over lockdown. Something I’d never done before, and I just thought, ‘Fuck it, I’m gonna do this.’ One song in, it worked and then I just carried on writing. And I was writing with this artist and it just started working for every song, and almost every song is DADGAD.

“So that record is really interesting and that was mostly written on a '50s [Gibson] LG-1, which my wife bought me for my birthday years ago. At the time I was like, ‘This is lovely, but it’s hard work.’ And, gradually, it’s become my number-one writing guitar. I’ve slowly fallen in love with it. Really small body. Quite hard work. No bottom-end. And quite a raw sound. And I started putting it into DADGAD and really picking it, and I just adore this guitar.”

I sunk into DADGAD over lockdown. Something I’d never done before, and I just thought, ‘F**k it, I’m gonna do this’

Do you have any more plans as a solo artist?

“I’ve written a new album and I’m two-thirds of the way through recording it. It’s got a title and running order, all of that stuff is there, and I just have to get my head down to finishing off the parts. So I’m really excited about that. It’s taken me a long time to make myself feel comfortable about doing it, and also to give myself a real reason to write.

“I don’t like writing songs just because I need to do it. I want there to be a reason to do it. I want there to be something I’m inspired by that makes me go and do it. And so I’m in that place at the moment. So next year is quite exciting for me, I must admit.”

- People Move On is out now via Edsel Records.

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.