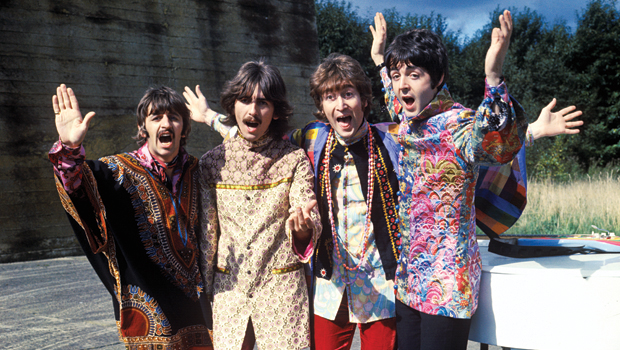

The Beatles on the Road to 'Magical Mystery Tour'

The first day of June 1967 saw the release of an album that would provide the soundtrack for the approaching summer. For weeks to come, nearly everywhere you went, you would hear it: on the radio, in restaurants and clubs, from passing automobiles and through the open windows of homes, where it spun repeatedly on turntables.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was the album, and it was the Beatles’ latest and greatest achievement. The record defined not only that summer—dubbed the Summer of Love—but also the year and, eventually, the moment at which pop music became art. Until then, pop music had been written and produced for teenagers, and teenage music was not supposed to be like this: sophisticated, challenging, as carefully wrought as an objet d’art.

With Sgt. Pepper’s, the Beatles redefined the genre even further than they had the previous year with Revolver, creating grand productions punctuated by calliopes, classical Indian instruments, orchestras, animal noises, sound effects and layered crashes of piano chords. Pressed onto a 12-inch slab of vinyl and packed into a baroque, parti-colored sleeve, the music on Sgt. Pepper’s constituted not just an album but an event—a pivotal moment in the development of Western music.

So what do you do for an encore? Seizing the moment, the Beatles might have carried onward with a music project even grander, or defied expectations and taken a completely different artistic direction. In fact, they would do both in 1968 with their sprawling, stripped-down double-disc White Album.

But in the meantime, in late April 1967, with the Sgt. Pepper’s sessions barely finished and the album still unreleased, they launched haphazardly into a new project based on, of all things, an art-film concept dreamed up by their bassist, Paul McCartney. Titled Magical Mystery Tour, it was designed from the beginning as a TV film that would include the Beatles both as actors and as musical performers. The idea had come to McCartney on April 11 during a return flight from the U.S. to Britain.

The Beatles had quit touring the previous August, and a film, he reasoned, would be a good way to keep them in the public eye. In fact, it would be little more than a container for six new Beatles songs: the title track, “Your Mother Should Know,” “The Fool on the Hill,” “Blue Jay Way,” “I Am the Walrus” and “Flying.” Accordingly, the film’s plot was slight and functional: a bus carrying the band and a group of tourists through provincial England comes under the power of a cadre of magicians (also played by the Beatles), after which strange things start to happen. As a story device, the bus tour was certain to appeal to British viewers.

“It was basically a sharabang trip,” George Harrison said, “which people used to go on from Liverpool to see the Blackpool Lights,” a popular electric light display presented in the autumn months. “They’d get loads of crates of beer and an accordion player and all get pissed, basically—pissed in the English sense, meaning drunk. And it was kind of like that. It was a very flimsy kind of thing.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As John Lennon saw it, “It’s about a group of common, or ‘garden,’ people on a coach tour around everywhere, really, and things happen to them.”

No one in the group took the concept very seriously. The Beatles didn’t hire big-name screenwriters or a visionary director, or pour loads of money into the production. They simply signed up some character actors—including Jessie Robins as Ringo Starr’s bellicose, fat aunt, and eccentric Scottish poet and musician Ivor Cutler as the skeletal Buster Bloodvessel—hired out a coach, and hit the English countryside, filming a series of bizarre and droll sketches designed to support the title’s dual notions of magic and mystery.

“We rented a bus and off we went,” Starr says. “There was some planning. John would always want a midget or two around, and we had to get an aircraft hangar to put the set in. We’d do the music, of course. They were the finest videos, and it was a lot of fun.”

“We knew we weren’t doing a regular film,” McCartney says. “We were doing a crazy, roly-poly Sixties film.”

Indeed, the entire last half of 1967 was a strange time for the Beatles. Concurrent with the start of Magical Mystery Tour, they’d agreed to provide music for Yellow Submarine, an animated film based on their 1966 song of the same name from Revolver. Film productions had been a secondary aspect of the Beatles’ career ever since their 1964 feature film debut, A Hard Day’s Night. Now, however, they were involved in two films simultaneously. In addition, at nearly the same time that they’d agreed to Yellow Submarine, their manager, Brian Epstein, had signed them up to appear on Our World, a live global television event scheduled for June 25, for which the Beatles would compose and perform a new composition, “All You Need Is Love.”

Clearly, there was no shortage of projects for the group to work on. The problem was that, after an intense five months of recording Sgt. Pepper’s, they found it difficult to focus again on a new project, let alone three.

“I would say they had no focus, absolutely,” says Ken Scott, the Abbey Road engineer who ran the mixing console for several of Magical Mystery Tour’s songs. (His recollections of working with the Beatles as well as recording classic albums by David Bowie, Elton John, Supertramp and others are chronicled in his new memoir, Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust.) “It was kind of weird, ’cause I’d worked with them from A Hard Day’s Night through Rubber Soul as a second engineer, and I’d seen sort of how they would get down to work and all of that kind of thing. But on Magical Mystery Tour, the focus didn’t seem there. It was kind of thrown together.”

A survey of the group’s recording sessions from this period bears out his point. Between the completion of Sgt. Pepper’s on April 21 and the conclusion of sessions for Magical Mystery Tour the following November, the group recorded about an album’s worth of songs, several of which remained unmixed or unfinished for another year, some for even longer. In addition to the six Magical Mystery Tour tracks, the Beatles recorded McCartney’s “All Together Now,” and Harrison’s “Only a Northern Song” and “It’s All Too Much,” all of which ended up on the Yellow Submarine soundtrack, released in January 1969. Also started during this time was the recording of Lennon’s novelty tune “You Know My Name (Look Up the Number),” which remained unfinished until late 1969 and unreleased until 1970.

Which is not to imply that the Beatles lacked motivation. Geoff Emerick, who engineered Revolver, Sgt. Pepper’s and much of Magical Mystery Tour, believes their almost nonstop working schedule from 1962 through 1967 had everything to do with their lack of direction in the wake of Sgt. Pepper’s. In his 2006 memoir, Here, There and Everywhere, he recalls, “People don’t realize how hard the Beatles worked in the studio, and on the road. Not just physically, but psychologically and mentally it had to have been incredibly wearying. Now”—with the completion of Sgt. Pepper’s—“it was time to let off some steam. All throughout the spring and summer of 1967, the prevalent feeling in the group seemed to be: after all those years of hard work, now it’s time to play.

“Personally, I saw it as just a bit of harmless light relief after all the intensity that had gone in to Pepper. The question was, how long could it last before they got bored?”

For now, there was no chance of that happening. The filming of Magical Mystery Tour wouldn’t take place until mid September, but in the meantime, there were songs to be written and recorded for the film, not to mention work to be done for Yellow Submarine and Our World. McCartney had written Magical Mystery Tour’s title track around the same time that he’d come up with its concept, so it was the first of the project’s tunes to be recorded. The bulk of the recording was done over five dates from late April to early May, in a set of sessions that featured the same sort of inventiveness that the Beatles had brought to Sgt. Pepper’s. Richard Lush, the second engineer on those dates, recalls, “All that ‘Roll up, roll up for the Mystery Tour’ bit was taped very slow so that it played back very fast. They really wanted those voices to sound different.”

By the end of the fourth session, the group had spent nearly 27 hours on the track. It was a tremendous amount of time to devote to a single recording, demonstrating how completely the Beatles had taken over Abbey Road as an incubator for their musical ideas. Ken Scott says those long hours were the reason many of Abbey Road’s senior engineers didn’t want to work with the Beatles.

“The old-timers were all in their forties,” Scott says. “They had families, and they had got totally used to working 10 to 1, 2:30 to 5:30, 7 to 10, whereas the Beatles didn’t work on those schedules. So they didn’t like it because of that, primarily.” Indeed, on May 9, with “Magical Mystery Tour” completed, the Beatles spent more than seven hours—from 11 p.m. to 6:15 the next morning—jamming unproductively in the studio. Even the durable George Martin, their producer, sneaked out early on that session.

For the time being, Magical Mystery Tour ground to a halt as the Beatles focused on recording songs for Yellow Submarine and preparations for the Our World television program on June 25. The TV show was especially important, as it was the first live, global satellite TV production. Fourteen countries participated in the two-and-a-half-hour production with segments of arts and sports performances, cultural events and even broadcasts of babies being born. It’s estimated that more than 400 million people the world over viewed the program.

Undoubtedly, the highlight for most young viewers was Britain’s contribution, featuring the Beatles performing “All You Need Is Love.” Written for the event by Lennon, the song was a well-timed missive from the counterculture to the established order. With the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War still fresh in the news and the United States’ Vietnam escalation dragging on, Our World provided a platform for the Beatles to spread a message of peace. “Because of the mood of the time, it seemed to be a great idea to do that song,” Harrison said. “We thought, Well, we’ll just sing ‘all you need is love,’ because it’s a kind of subtle bit of PR for God, basically.”

Though Lennon, McCartney and Harrison performed their parts live on air, much of the song’s backing track was prerecorded during a one-day session at Olympic Studios on June 14 (see sidebar, page 50) and in subsequent sessions at Abbey Road, in order to make the performance go as smoothly as possible. Which it did—just barely.

“We had prepared a track, a basic track, of the recording for the television show,” George Martin says. “But we were gonna do a lot live. And there was an orchestra that was live… And just about 30 seconds to go on the air, there was a phone call. And it was the producer of the show, saying, ‘I’m afraid I’ve lost all contact with the studio. You’re gonna have to relay instructions to them—’cause we’re going on air any moment now!’ And I thought, My god, if you’re gonna make a fool of yourself, you may as well do it properly in front of 200 million people!”

“The man upstairs pointed his finger,” George Harrison recalled, “and that’s it. We did it, one take.” After a few post-show overdubs, the song was complete and ready for its release as a single on July 7.

And with that, the Beatles abruptly went on hiatus. For the next two months, Magical Mystery Tour was put on hold. Not another note would be recorded for it until late August.

With nothing to do, the Beatles wandered in ways only the very rich can. They rented a boat and sailed up the coast of Athens, shopping for an island on which they could plant themselves and their growing commercial empire. “We’re all going to live there,” Lennon said. “It’ll be fantastic, all on our own on this island.” The idea came to nothing. Adrift in the Summer of Love, they dropped acid, and lots of it, particularly Lennon and Harrison.

Late in the first week of August, Harrison and his wife, Patti Boyd, traveled to San Francisco, drawn by the news of the burgeoning hippie scene in the Haight-Ashbury district. The experience was disheartening. Harrison thought he’d find a community of doe-eyed enlightened beings. Instead, he encountered young dropouts who were constantly on drugs. “That was the turning point for me,” he said. “That’s when I went right off the whole drug cult and stopped taking the dreaded lysergic acid.”

- Indian culture and mysticism held a growing fascination for Harrison. Seeking a release from drugs, he turned to meditation. Through a friend, he learned that Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the leader of the Transcendental Meditation movement, would be speaking at the Hilton Hotel in London on August 24. He decided to go and picked up tickets for his bandmates, in case they wanted to come along. In the end, all but Ringo Starr attended.

- “We went along, and I thought he made a lot of sense,” McCartney says. “I think we all did, because he basically said that, with a simple system of meditation—20 minutes in the morning, 20 minutes in the evening, no big sort of crazy thing—you can improve the quality of life and find some sort of meaning in doing so.”

Immediately after the presentation, Harrison, Lennon and McCartney had a private audience with the Maharishi. At his request, they agreed to travel with him on the following day to Bangor, Wales, for a seminar and retreat. Photos from the Bangor event show all four Beatles, clad in psychedelic finery, sitting on a dais with the Maharishi, who was clearly reveling in the attention that the group was bringing to his movement.

“I was really impressed with the Maharishi, and I was impressed because he was laughing all the time,” Starr recalls. “And so we listened to his lectures, and we started meditating. We were given our mantras. It was another point of view. It was the first time we were getting into Eastern philosophies.”

But while the Beatles were achieving a higher level of consciousness in Wales, their world was falling apart back in London. On August 27, as they meditated with the Maharishi, their manager Brian Epstein died from an accidental overdose of sleeping pills.

“That was kind of stunning,” McCartney says. “’Cause we were off sort of finding the meaning of life, and there he was—dead.”

Both friend and business manager to the Beatles, Epstein had worked tirelessly to secure a recording contract for them back in 1962. His efforts had landed them an audition with George Martin, who subsequently signed them to EMI’s Parlophone Records. Since then, Epstein had overseen their growing empire, leaving the Beatles’ free to focus on their music. Harrison said of his passing, “It was a huge void. We didn’t know anything about, you know, our personal business and finances. He’d taken care of everything… It was chaos after that.”

On September 1, within days of Epstein’s death, the Beatles gathered at McCartney’s house in London’s St. John’s Wood and put their minds back to the task of making music. A plan to study Transcendental Meditation at the Maharishi’s retreat in India was put on hold. Magical Mystery Tour was now a top priority. Perhaps they needed something to take their minds off their grief. Or maybe, as Lennon suggested, Epstein’s death put the fear of god into them that their own days were numbered. “I knew that we were in trouble then,” Lennon recalled. “I didn’t really have any misconceptions about our ability to do anything other than play music. I was scared, you know. I thought, We’ve fucking had it now.”

As the creative force behind the film, McCartney had been busy working on the film’s loose script. “He and John sat down, I think in Paul’s place in St. John’s Wood,” recalled Neil Aspinall, the Beatles’ longtime friend and road manager. “And they just drew a circle and then marked it off like the spokes on a wheel. And it was really, ‘We can have a song here, and we can have this here, we can have this dream sequence there, we can have that there,’ and they sort of mapped it out. But it was pretty rough.”

The Beatles had made little headway on Magical Mystery Tour since May. On August 22 and 23, just days before Epstein’s death, they’d attempted to record “Your Mother Should Know” at Chappell Recording Studios, an independent facility in central London (Abbey Road had been booked and unavailable.) But now it was time to knuckle down. On September 5, the Beatles regrouped in the familiar confines of Abbey Road’s large Studio One to do just that, starting with a new Lennon composition, “I Am the Walrus.”

There was a new face on the session: Ken Scott. Like Geoff Emerick, Scott was one of the many young men who’d climbed up through EMI’s rigorous training program. He had worked as second engineer—a tape machine operator—on previous Beatles sessions, but to date he had never engineered a recording. On this day’s session, he was working as second engineer to Emerick, who had engineered nearly every Beatles session from Revolver forward. Emerick’s ingenuity with recording equipment, his ideas about microphone placement and his talent for interpreting and fulfilling the Beatles’ growing desire for audio effects had quickly made him an invaluable part of the group’s production team.

So Scott was understandably shocked when, less than two weeks later, on September 16, he arrived at Abbey Road and was told to take over as the Beatles’ engineer; Emerick had abruptly left for an extended vacation. “I was completely thrown in at the deep end, put behind a board having never touched it before,” Scott recalls. “That first session I had no idea what the hell I was doing.”

Scott did his best and carried on with the session, a remake of “Your Mother Should Know,” using the same mic setups and recording gear that Emerick had been using. Under the circumstances, it’s not surprising that Scott can’t recall what guitars, basses and amps were used on Magical Mystery Tour, but photos, videos and the film offer suggestions. With respect to guitars, the Beatles most likely used the same gear that they used on Sgt. Pepper’s, though it may not appear that way to the untrained eye. As the psychedelic craze caught on in the summer of 1967, Harrison, Lennon and McCartney each gave their guitars wild paint jobs. Harrison treated his 1961 Sonic Blue Stratocaster, acquired in 1965, to a Day-Glo rainbow finish that he applied himself, and redubbed the guitar “Rocky.” He can be seen playing the guitar in the “All You Need Is Love” broadcast, during which he performed his guitar solo live, and in the “I Am the Walrus” segment of Magical Mystery Tour. Likewise, McCartney embellished his Rickenbacker 4001S bass with a dripping pattern using white, silver and red paint; the bass can be seen in the “All You Need Is Love” broadcast, the “I Am the Walrus” segment and the video for the single “Hello, Goodbye,” recorded around the same time as Magical Mystery Tour. Lennon continued to use his Epiphone Casino, which he had spray-painted either white or grey, as well as his Gibson J-160E acoustic-electric, to which he eventually had a psychedelic finish applied.

As for amps, McCartney used a Vox 730 guitar amp—a valve/solid-state hybrid—with a 2x12 730 cabinet for his bass. Lennon and Harrison can both be seen using Vox Conqueror heads with 730 cabinets in the “Hello, Goodbye” video. Other amps in their possession at this time included a Fender Showman, a Fender Bassman head with a 2x12 cabinet, and a Selmer Thunderbird Twin 50 MkII.

Though Scott originally relied on Emerick’s miking and engineering techniques, he found his comfort zone as the weeks stretched on. Eventually, he began to experiment with sounds, much as Emerick had before him. The Beatles’ sessions proved perfect for this. “As a young engineer learning, working with the Beatles was absolutely incredible, for two reasons,” Scott says. “One, there weren’t time limits. With EMI’s traditional three-hour sessions, you didn’t have time to experiment because you had to get a couple of tracks recorded in three hours. With the Beatles, time was unlimited. Two, there was the freedom to experiment. The Beatles always wanted things to sound different, and that gave you the opportunity to try things. I could use completely the wrong mic in completely the wrong place, and completely screw up the EQ so it sounds atrocious. But I would learn from that. And the Beatles could just as easily hear it and say, ‘Oh, that’s awful—but we’ll use it.’” He laughs. “Because they wanted everything to be different. So just in terms of experimentation, they were the most amazing band to be able to work with.”

There was no greater example of experimentation on Magical Mystery Tour than the mono mixdown session for “I Am the Walrus,” on the night of September 29. The song itself was a marvel of wordplay and orchestration—as Lennon said, “one of those that has enough little bitties going to keep you interested even a hundred years later.” No song in the Beatles’ catalog features as many literary and social references in its lyrics as “I Am the Walrus” does. In writing it, Lennon drew on references to Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (the walrus), playground nursery rhymes, the Hare Krishna movement, Edgar Allen Poe and even the Beatles’ own “Lucy in the Sky.” Complementing the bizarre lyrics was an equally vivid and evocative orchestral score for strings, horns, clarinet and 16-piece choir, which was recorded on September 27 in Studio One.

But the crowning touch was applied at the September 29 mixdown. Although the song was essentially finished, Lennon wasn’t ready to sign off on the track. “John felt that the song was missing something,” Scott says. Lennon’s idea was to add to the last half of the recording the sound of a radio dial being turned through its frequency range, catching snippets of live programs as well as the static in between stations. But unlike other overdubs, this one would be added live at the mixing stage, thereby embedding the radio broadcast permanently into the final recording. It was an unusual way to work, but with no free tracks available on the four-track tape, it was the only way to proceed.

The job of dial turning fell to Ringo Starr. During one of the two takes performed that night, he let the dial come to rest on a BBC broadcast of Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Lear. “I can’t remember if he just stopped doing it or if John told him to stop at that point whilst we were mixing,” Scott says. “But it finished up being that section from King Lear. The fact that it finishes up just being one station almost goes against what [Lennon] was after. He very much wanted it [the radio station] just sort of changing the entire time.” As it happened, the extract from King Lear—depicting the violent death of the steward Oswald—fit perfectly. Its disturbing dialogue and the cadences of the actors’ speech meshed as if on cue with the song’s complex arrangement. “It was pure luck,” Scott says, “because it was [mixed] live. We never could have recreated it.”

The surreal sounds of “I Am the Walrus” are nearly equalled by “Blue Jay Way,” Harrison’s contribution to Magical Mystery Tour. The song is among the best of his compositions from this period, a haunting piece from which the group fashioned a sonically fascinating recording. Harrison wrote the song in August while staying at a rented house on Blue Jay Way in the L.A. neighborhood of Hollywood Hills. He was waiting for Derek Taylor, the Beatles’ press officer, to arrive, but Taylor had trouble finding the house. As the hour grew later, fog descended, further delaying his arrival. Feeling sleepy, but not wanting to doze off, Harrison sat down at a Hammond organ in the house and began composing a new song fresh from the experience of waiting for Taylor’s arrival, punctuated by a mournful chorus on which he pleads, “Please don’t be long, for I may be asleep.”

The recording of “Blue Jay Way” took place in Studio Two, commencing on September 6 and continuing through the 7th. As evidence that the Beatles were plowing ahead on Magical Mystery Tour following months of inactivity, the song was begun while the group was still at work on “I Am the Walrus.” “Blue Jay Way” features a kitchen-sink application of audio effects, including vocals through a Leslie speaker (first used on Revolver’s “Tomorrow Never Knows”), flanging on the drums and, on the stereo mix of the song, an overdubbing of backward background vocals.

The result is a recording that, while not as dense as Lennon’s “I Am the Walrus,” is every bit as satisfying. After standing in the shadows of Lennon and McCartney, Harrison was clearly coming into his own. “As each one was taking more control of their own songs, he didn’t have to rely on the others quite so much,” Scott says. “So I think that gave him more freedom, more flexibility to complete his songs, and that they were turning out better and better all along.”

On September 8, with the basic tracks for “Blue Jay Way” completed, the Beatles turned their attention to “Flying,” a slow blues in C that was unusual in two respects: not only was it an instrumental (it’s la-la-ing vocals notwithstanding) but all four Beatles shared a co-writing credit on it. At this stage, the song was called “Aerial Tour Instrumental” and included a saxophone solo (later erased) from a Mellotron, the tape-based sample player that had provided the flutes on “Strawberry Fields Forever” (and which also provides the windwood lead instrument and background string sounds on “Flying”). More overdubs were added on September 28, including ethereal sounds from tape loops created by Lennon and Starr, thereby stretching the recording’s length to 9:36. The song was edited down to 2:14 and fades out with the tape loops, though the unused portion of the song didn’t go to waste: it was saved and reused as incidental music in the movie.

McCartney’s track “The Fool on the Hill” was the last song to be undertaken for Magical Mystery Tour, beginning on September 25 in Abbey Road’s Studio Two. According to the bassist, he had written it while at the piano in his father’s house, in Liverpool, following the Beatles’ August trip to the Maharishi’s seminar in Wales. The “Fool” referred to in the song is actually the Maharishi, whom McCartney saw as a misunderstood mystic. “His detractors called him a fool,” he explained. “Because of his giggle he wasn’t taken too seriously.”

Despite its rather simple arrangement, “The Fool on the Hill” contained numerous overdubs, including recorder, penny whistle and harmonicas, which quickly filled up the four-track tape. On October 20, McCartney decided to add a flute solo to the song, but with no tracks available, the tape would have to be bounced down—for the second time since it was begun—to another reel of tape, onto which the flute overdubs could be added.

Rather than subject the song to yet another transfer, a procedure that can add hiss and degrade sound quality, George Martin decided to implement a technique that had been used for “A Day in the Life,” on Sgt. Pepper’s. For that song, Abbey Road engineer Ken Townsend had devised a way to link two four-tracks to play in sync, using a pilot tone on one track to control the speed of the second machine. “It was extremely trustworthy, except for one little thing,” Scott says, “and that was the starting time of them. Once you got them running together, yes, they were perfectly in sync. The problem was just starting them up together, because each machine starts at a different speed every time.”

Apparently, by the time they recorded “The Fool on the Hill,” everyone had forgotten how much trouble the system could be. “The problem was that on the second four-track, [the flutes] didn’t come in till about a quarter of the way into the song,” Scott says. “So we wouldn’t know until they came in whether or not the two machines were running in sync. Eventually we got it so that they ran in sync for probably just two mixes: the mono and stereo. Yeah. It wasn’t fun.”

By the middle of November, all six Magical Mystery Tour tracks were completed, mixed and mastered. On December 8, the finished work was released in England as a gatefold package containing two extended-play 45-rpm records. In the U.S., where EPs had failed to catch on, Capitol Records, the Beatles’ American label, issued it as a full-length album containing the six songs on one side and five other Beatles tracks released as singles in 1967: “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Penny Lane,” “All You Need Is Love,” “Baby You’re a Rich Man” and “Hello, Goodbye.” In either of its musical formats, Magical Mystery Tour was a hit with both the public and critics.

The film was not. Shown on the BBC on Boxing Day—the day after Christmas, and a holiday in Britain—Magical Mystery Tour was universally panned as a confusing and self-indulgent mess. Having little in the way of plot, it derived its entertainment value from the Beatles’ musical performances as well as cinematography that was rich with the psychedelic colors that typified the times.

“And of course they showed it in black and white!” Ringo Starr says. “And so it was hated. They all had their chance then to say, ‘They’ve gone too far. Who do they think they are?’”

McCartney, as the film’s instigator, takes the long view. “I defend it on the lines that nowhere else do you see a performance of ‘I Am the Walrus,’” he says. “That’s the only performance ever.”

No such defenses are necessary when it comes to the music. It’s as fine as anything on Sgt. Pepper’s, and it shows at times an even greater command of arrangement and studio production. Clearly, the Beatles were getting a firmer hand on the intricacies of their music.

But there is a weariness to the music as well, a tangible sense of Sgt. Pepper’s expectant summer giving way to Magical Mystery Tour’s melancholy autumn. The six songs destined for Magical Mystery Tour were written before Epstein’s death late that August, but there is a dry, funereal whiff to most of those that were recorded after it, as if the Beatles were mourning his loss through the by now ritual sessions at Abbey Road. “I Am the Walrus” is wonderfully macabre and grotesque with its maniacal background vocals and Lennon’s seething croup of a voice, his baleful shouts growing until, by the coda, he sounds like a huffing blast furnace. Harrison’s haunting “Blue Jay Way” emerges sinisterly out of silence, its dreamy Lydian melody, sustained organ chords, unsettling cello lines and ghoulish background vocals evoking the song’s theme of unanswered longing and physical dislocation. McCartney’s “Fool on the Hill” is plaintive and abandoned, its wistful flutes and plodding chorus of bass harmonicas inducing cloud-engulfed vistas of lonely supernal peaks.

And then there is the dirgelike 12-bar-blues burlesque of “Flying,” a perversely psychedelic defiling of the genre that gave birth to the rock and roll from which the Beatles emerged and, in 1967, briefly took flight. Within weeks of the dawn of 1968, they would land once again on the solid ground of rock and roll and folk, recording McCartney’s barrelhouse R&B tribute “Lady Madonna” and, one day later, Lennon’s gentle acoustic ode “Across the Universe.” A dream was over. A new one was just beginning.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of Guitar Player magazine, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.

“This particular way of concluding Bohemian Rhapsody will be hard to beat!” Brian May with Benson Boone, Green Day with the Go-Gos, and Lady Gaga rocking a Suhr – Coachella’s first weekend delivered the guitar goods

“A virtuoso beyond virtuosos”: Matteo Mancuso has become one of the hottest guitar talents on the planet – now he’s finally announced his first headline US tour

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)