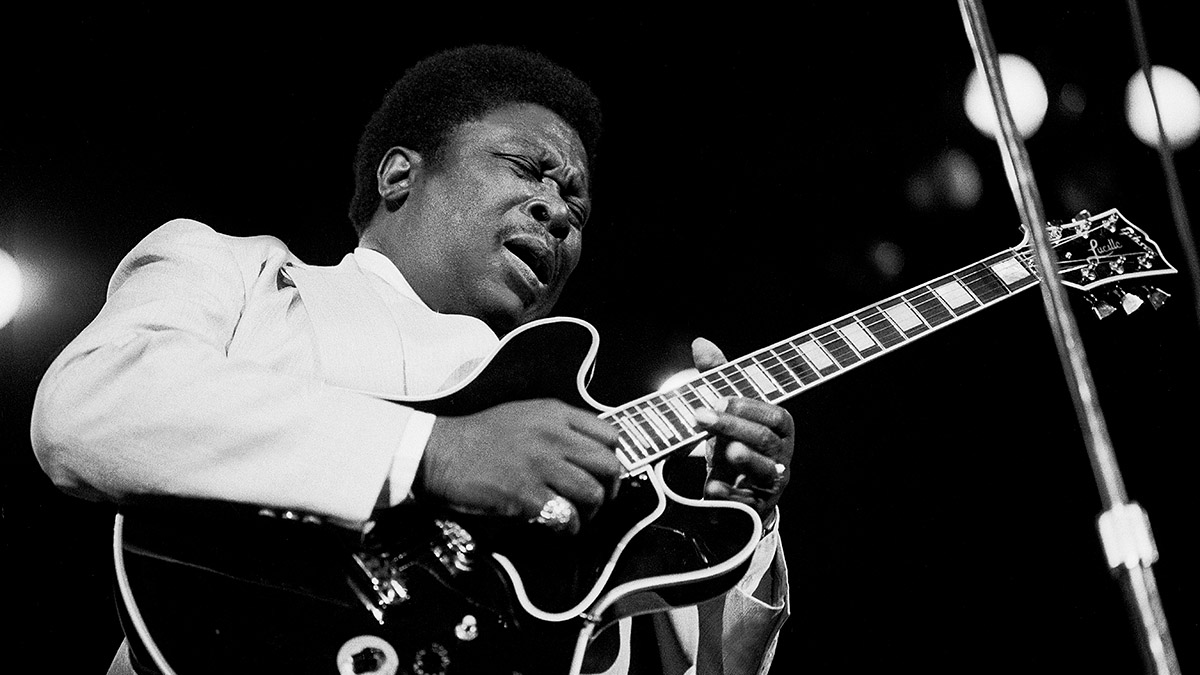

“When I play the trill with my finger, my hand is not on the neck at all. It all comes from the wrist”: The story of B.B. King, the greatest blues guitar player of all time

How the King of the Blues heard his calling, found a guitar, and developed a style that made him the undisputed greatest of all time

The man born Riley B. King had every right to play the blues. Revered by peers such as Buddy Guy, Freddie King, Albert King, Chuck Berry and Otis Rush, he also garnered a plethora of later admirers, from Clapton and Hendrix to John Lennon and Keith Richards.

Indeed, pretty much every guitarist that ever bent a string, added vibrato and let that note sing, owes something to King’s style. Today’s fine roster of bluesers, including John Mayer, Eric Gales, Joe Bonamassa, Gary Clark Jr., Susan Tedeschi, Joanna Connor and Derek Trucks were all, directly or otherwise, affected by him.

Even Lennon, when asked if there was anything more he’d like to achieve said, “Yes, to play guitar like B.B. King.” Well, listen to John’s solos on The Beatles’ Get Back and the influence is there for all to hear. And check out Peter Green’s sublime guitar on Fleetwood Mac’s Need Your Love So Bad – it has King’s blues DNA all over it.

First steps

Born on the Berclair Cotton Plantation in Itta Bena, Indianola, Mississippi in 1925, King’s parents were sharecroppers, and from a young boy into his early teens Riley picked cotton, worked on a cotton ‘gin’ (the ‘engine’ that separated the fibres from the seeds), or drove a tractor. Due to his parents splitting up when he was just four, King’s maternal grandmother looked after him until she died a few years later.

During his time in and around Indianola, Riley would have witnessed endemic racism, segregation, deprivation, even the horrors of lynching. Riley, though, sought to distance himself from the brutal things he saw, never wanting his career to be defined by them. As blues legend Buddy Guy tells it: “Whenever we’d have that conversation he’d always lead away from it, making me think: there’s stuff you don’t want to tell here.”

Thankfully, Riley discovered music, initially at his local church when a preacher taught him a few chords on the parlour guitar he’d been given by slide guitar-playing cousin, Bukka White, but also in Indianola’s bustling nightlife. Great blues and jazz artists would come through town to play.

Too young to venture in, Riley would sneak round the back to listen, totally absorbed by the music he was hearing. By this time, King had also acquired a better instrument with money forwarded from his salary by the plantation owner. It cost 15 dollars.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In 1943, King joined a local gospel group playing in churches in and around Indianola. King, already into the blues, once described how when he played a gospel song, people would pat him on the head and say, “That was good, boy”, but give him nothing for his troubles. When he knocked out a blues tune he’d receive the patronising pat on the head, “but this time they’d put something in the hat”, he quipped.

Blues Boy

Blues was Riley’s ticket off the plantation. In 1948 he moved to West Memphis, Arkansas, where he began making a name for himself in the bars and clubs, and through appearances on Sonny Boy Williamson’s radio show.

He then gained a regular spot on Radio WDIA, across the river in Memphis, Tennessee. The station re-christened its hit-signing Beale Street Blues Boy, shortened to Blues Boy, then B.B. (he had both ‘Bee Bee’ and ‘B.B. King’ hand-painted on his guitars).

By this time, King had acquired his first Gibson, a small-bodied non-cutaway L-30, but his jobs earned him enough to buy the instrument with which he’d cut his first record, a P-90‑equipped Gibson ES-125.

In 1951, King recorded Lowell Fulson’s 3 O’Clock Blues. It hit the top of the R&B charts and put King squarely on the map. Even then, his delivery was exquisite. The style, while yet to be refined, was instantly recognisable; effortless vocals punctuated with succinct and idiomatically faultless guitar lines.

While it’s easy to think it all started with King, on his road to creating the style that’s so recognisable today, B.B. found his own guitar heroes. First of these was T-Bone Walker. Texas-born Walker developed a fluid, jazzy style that oozed class, and King found his warm Gibson tone and perfect note choices irresistible.

“He was the first electric guitar player I heard on record, and I had to have one, too,” King recalled. “I can still hear T-Bone in my mind from that first record, Stormy Monday.”

Next, enter Benny Goodman Orchestra guitarist Charlie Christian. “Oh boy,” sighed B.B. as he recalled first hearing the groundbreaking jazz guitarist. “Charlie Christian was amazing. He was a master of diminished chords, and a master of new ideas, too.”

King’s next influence, a Romani guitarist from Liberchies in Belgium, is perhaps more surprising. As King put it: “A friend of mine who was in the army came back to Mississippi and said, ‘I’ve brought some records back and I want you to listen to this fella.’ He then played me Django Reinhardt. I instantly fell in love with him, his guitar seemed to talk. So those three are my guitar idols.

“Each one had something that seemed to go through me like a sword. It’s something that happens and you just know, on some spiritual level, that this was meant for you to hear.”

The road to Lucille

Django had played a Selmer Maccaferri guitar, but Walker and Christian both used Gibsons, so it’s unsurprising that King had also chosen the Gibson route. From the earlier L-30 and ES-125 he graduated to flashier archtops like the L-5 and three-pickup ES-5 (as used by T-Bone), a short-scale Byrdland, and the jazzers’ favourite, an ES-175. He also had brief flirtations with a Les Paul Goldtop and a single-pickup Fender Esquire.

I’m horrible with chords, so I get somebody else to play them

B.B. King

By trialling these various instruments King was clearly waiting for the perfect model, but it wouldn’t roll off Gibson’s production line until 1958. This was the ES-300 series, incorporating ES-330, ES-335, ES-345 and ES-355. King sporadically played all four models, but eventually settled on the blingiest, the ES-355, which the company later tweaked to create the B.B. King ‘Lucille’ model.

Why Lucille? While playing at a dance one cold Arkansas night, a fight broke out. During the fracas, which was over a woman, someone kicked over the burning pail of kerosene intended to keep the place warm. Instead the venue caught alight, and King ran in to rescue his beloved L-30 from the flames. He later learned that the woman’s name was Lucille, and every subsequent B.B. guitar would bear her moniker.

At its best, King’s guitar style was a fluid mix of major and minor pentatonic licks, mixed with complex jazz-style flurries. From his early playing years it morphed from a simplified version of the Lonnie Johnson, Charlie Christian and Django melodic ‘chord tone’ style, as heard on 3 O’Clock Blues, to the more typical pentatonic ‘box shapes’ of T-Bone Walker, which you can hear on When My Heart Beats Like A Hammer from 1988’s collection of B.B.’s early recordings entitled B.B. King – Do The Boogie.

The ‘B.B. Box’

By 1965 and the legendary Live At The Regal album, King’s style, now fully formed, had come to revolve around what’s known as the ‘B.B. box’. Looked at in the key of A, King would locate the root note A with his first finger at the 10th fret, second string, using this as ‘home’.

From here it was easy to reach all the key major and minor pentatonic notes, both on the string above (the 5th interval at the 12th fret, pushed up to the 6th and flat 7th with a two or three-fret bend, and the flat 5 ‘blue’ note located in between).

The 2nd and flat 3rd situated one and two frets above ‘home’ on the second string, were easily bent up to major 3rd and 4th, and on the next string down were lower-octave 5th, 6th and flat 7th, at the 9th, 11th and 12th frets. That’s a lot of musical information within a short, four-fret spread.

King’s fluttering finger vibrato is also the stuff of legend. Loving the slide guitar vibrato of cousin Bukka White but not wanting to play bottleneck himself, B.B. created a way to emulate it by wobbling and rotating his first finger on the string. “To get the vibrato started, my thumb is on the neck. But when I play the trill with my finger, my hand is not on the neck at all. It all comes from the wrist,” he once described.

King rarely played rhythm. “I’m horrible with chords,” he once confessed to U2’s Bono, “so I get somebody else to play them.” For 22 years this was his big band’s guitarist, Leon Warren.

As frontman, King would often sing a line and answer it with a guitar phrase. And when he wasn’t playing, his fretting hand would hang loosely by his side, or he’d hold both arms up in jubilation.

The long road

Tonally, King went from ultra-clean to pretty overdriven, usually through Fender amps or, from the late ’70s onwards, Gibson Lab Series combos. He loved position two on his ES-355’s five-way Varitone switch, which lent a nasal, ‘out of phase’-type tone to his phrases. You can hear all of B.B.’s classic tones and licks on the incredible aforementioned album: 1965’s Live At The Regal.

B.B. King spent his life touring – playing upwards of 300 shows most years – and recording. He sold over 50 million albums and collaborated with everyone from Gary Moore to Elton John.

Check out 1971’s In London album, featuring guests Peter Green, Steve Winwood and Ringo Starr; 2005’s B.B. King and Friends: 80 with Eric Clapton, Mark Knopfler, Billy Gibbons, Bobby Bland, and Sheryl Crow; and King’s most successful album, the co-headliner with Clapton, Riding With the King from 2000, which sold over 3.5 million copies and took the 2001 Grammy for Best Traditional Blues Album (King won 15 Grammys in total).

Always dressed to impress, B.B. wore tailor-made suits, fancy guitar straps, and that ultimate accessory – his gold-plated, pearl-encrusted Gibson Lucille. This never less than impeccable look was due to a word of early advice from Bukka White. “Bukka told me, ‘Riley, blues musicians should always dress like they’re going to the bank to borrow some money!’”

In the late '70s and early '80s Neville worked for Selmer/Norlin as one of Gibson's UK guitar repairers, before joining CBS/Fender in the same role. He then moved to the fledgling Guitarist magazine as staff writer, rising to editor in 1986. He remained editor for 14 years before launching and editing Guitar Techniques magazine. Although now semi-retired he still works for both magazines. Neville has been a member of Marty Wilde's 'Wildcats' since 1983, and recorded his own album, The Blues Headlines, in 2019.

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83