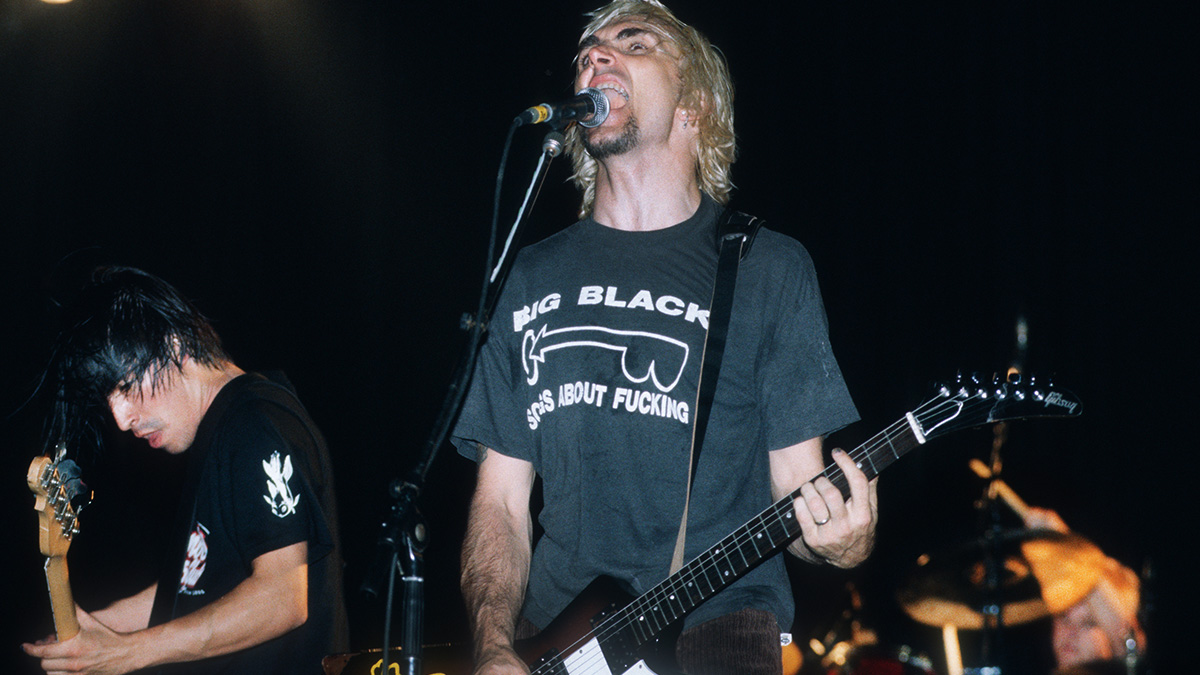

“I had a Fender Super Twin that was completely melted down – sparks were shooting out of the amp. I’m shocked we didn’t burn the place down”: Everclear’s Art Alexakis on the tenacity and dangerous amps that won him platinum-level success

The Everclear frontman/guitarist looks back at the heady days of the ’90s: the moments where he almost quit, the records that made him cringe, and how he crafted “the ultimate ‘f**k you’ to all the doubters”

By the time the sessions for 1993’s World of Noise began, Art Alexakis had reached the end of his rope. A raging punk-rocker at heart, the then 31-year-old songwriter had reached an impasse, leaving him in a make-or-break situation.

“God, if Everclear didn’t hit, man, I was fucking done,” Alexakis says. “I’d spent years trying hard to make it work, but nothing was happening. My back was up against the wall, and I knew I had to try something different. My kid was on the way, and life was staring me in the face, telling me, ‘Get this done, or get out.’”

Luck shined down on Alexakis as the underground success of World of Noise laid the groundwork for a major label deal with Capitol Records. Still, no one could have anticipated the breakneck triumph of Everclear’s follow-up records – Sparkle and Fade (1995) and So Much for the Afterglow (1997) – leading to fame and fortune via platinum-selling success.

“That was the ultimate ‘fuck you’ to all the doubters,” Alexakis says. “No-one believed in Everclear or me, at least not in the sense that we would go platinum. I don’t know what it was, though; it’s not like you can plan for that. Years of angst and upset built up, creating a storm of creativity that no-one saw coming.”

In the years since, Alexakis had soldiered on. There have been more hits and the inevitable downturn that all aging artists face. But none of that deters Alexakis; the West Coast native is still defiant, boundlessly capable of spinning off angelic pop tunes on the turn of a dime.

“I don’t think about matching what I’ve done,” Alexakis says. “I have no need to do that. I’ve done what I set out to do. As for the world today, we’ve got people who seem to be accepting less of each other, which sucks. I guess I’m still angry and still writing about sad stuff. But there’s so much bullshit in the world; I have to do my best to call people out on it when I see it. I won’t be led around like a donkey; I’d rather see myself as a tiger, you know?”

Still incensed with the same vigor that defined his heyday, Alexakis dialed in with Guitar World to discuss the music and moments that changed his life forever in the ’90s and beyond.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What are some of your most poignant memories of the ’90s?

“For me, there were a couple, but the main one was when I got the call that we had our first gold record with Sparkle and Fade. Our manager called us up and said, “Art, this thing isn’t just projected to go gold… it’s shipping gold this fucking week.” I just stood there, and all I could say was, 'That’s amazing,' I jokingly said, 'Hey, maybe we’ll go platinum or something.' And then he told me, 'It looks like it could happen, for real.' That record went on to go platinum, something I never thought could happen.”

How did that alter Everclear’s trajectory as the rest of the decade unfolded?

Sparkle and Fade’s success was a ‘thank you’ to everyone who believed in the band and me. And it was a ‘fuck you’ to everybody who didn’t

“It was a huge turnaround because no-one at Capitol Records thought we had that in us. We thought the record might do okay – but gold? Come on now. [Laughs] We weren’t signed for a big hit like many bands were, and Santa Monica hadn’t even been written when we signed the deal, so there was no sign of a ‘hit.’ So when we signed with Capitol, I started writing new songs immediately; I guess I felt a sense of urgency.

“In the ’90s, the way it worked was they built records around one song with the hope that it would be a hit; that’s generally how it went. But once I wrote Santa Monica, I knew I had a great song on my hands, but who can predict that a song will change everything? Okay, so, like I said, I was told the record would ship gold, possibly platinum. And then I get another call: ‘Art, I was wrong… the record is shipping platinum tomorrow.’

“That gave me chills; even thinking about it now, that conversation gives me chills. It was such a big deal, and it changed the trajectory of Everclear. Sparkle and Fade’s success was a ‘thank you’ to everyone who believed in the band and me. And it was a ‘fuck you’ to everybody who didn’t.”

The next record, So M – what does that record mean to you?

“I think that record is my masterpiece. It was validation for me because after Sparkle and Fade came out of nowhere to go platinum, many people doubted we could do it again. But the writing for that record wasn’t easy, and there were a lot of stops and starts. I went down one road; it didn’t work. I got my bearings, took a break, returned and had a whole new mindset. It went from a mediocre record that I was calling Pure White Evil to what would become So Much for the Afterglow.

“I remember I had this Pure White Evil record in January of ’97, and I wasn’t happy with it. I rewrote some things, changed the title and then went in and remixed the record with Andy Wallace. By the spring of ’97, it was called So Much for the Afterglow, and it was a new record. It was shorter, stronger and more representative of Everclear. And there’s a thing called 'cringe factor,' where you do something, and after the fact, you think, ‘Okay, is there anything that makes me cringe?’ I gotta say, with So Much for the Afterglow, there was very little cringe.”

Are there any Everclear records that do make you cringe?

“After So Much for the Afterglow, I wanted to make a double record called Songs from an American Movie. My idea was to make an album that was edgy but poppy at the same time. But my manager at the time talked me out of it; he said, ‘If we split it into two records, we can get an even bigger payday rather than doing the one double album.’ He played against my ego, ‘Hey, man, no one but Guns N’ Roses has really done this. You can do it too. Let’s cash in,’ and I bought into it.

“So the first album of the two, subtitled Learning How to Smile, is a pretty great record. I have no cringe factor. But volume two, Good Time for a Bad Attitude, sounds tired to me. There’s lots of cringe. It sounds tired because I was making two records in a year. Instead of 24 songs over two albums, I should have done 18 or 20 over one double album.

“If I had done that, it would have been perfect. It would have rivaled So Much for the Afterglow for my masterpiece. It was all ego. I shouldn’t have listened to my manager. But it was up to me, and I made a choice. I don’t blame anybody but myself.”

What are your memories of recording Wonderful?

“When I was working on that song, I had the music for it, and I was figuring out the chords on the piano. So I’m working on the song, and the guys in the band said, ‘Wow. You finally wrote about something positive.’ And I was like, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’ And they said, ‘It’s called Wonderful; that must be positive, right?’ If you know the song, you’ll remember it’s not very positive. They assumed it must be positive because it was called Wonderful.

“After that, I ended up flying down to L.A., and while I was on that plane, Wonderful fully formed. I decided to do it from the perspective of an inner-child, not necessarily me, but an amalgam of different people, including myself and even my own daughter.

“It became this song about a combination of kids from broken homes, and I wrote all those parts by singing them in my head on that plane ride. By the time I got to the studio, I walked up to the mic and did it in three takes.”

Has the shelf-life of that song surprised you at all?

“No. I don’t want to sound arrogant because I’m not. But when it was done, I was like, 'This is just about the most perfect pop song I’m ever going to write.' It builds the way it’s supposed to build. It ebbs and flows perfectly, and it crescendos just the right way. And my vocal take is one of my better ones, I think. It’s a great song, and there’s definitely no cringe factor there.”

Do you ever feel pressure to match songs like Santa Monica and Wonderful?

“Nope, I never have. Songs like that either happen or don’t. I didn’t write those songs to try and have hits. When I wrote those songs, that’s just what came out, and I’m grateful for that because they changed my life. Things were very different for me after I wrote those songs, bad in some ways but better in most.

“Even though those songs are two of my most well-known, I think the songs from Learning How to Smile are some of the best I’ve written. The expansiveness of the story, the buildup and the fall all make sense. I’ve been accused of not smiling enough, so those songs have a personal element, too. It’s bits and pieces of my life, and it all came together. But you can’t try to match that; it happens on its own or it doesn’t.”

Is there one electric guitar or piece of gear that you owned in the ’90s that holds particular significance?

“When we were recording World of Noise in late ’93, I had a semi-hollow body Guild Bluebird. I paired it up with a Fender Super Twin that was completely melted down. All the tubes were completely blown out, but the combination of those two produced a sound I couldn’t get again, even if I wanted to. The Guild was so beaten-up that it was impossible to keep in tune, and the amp was so fucked up that an insane and uncontrollable amount of feedback was coming off it.

It was so bad that sparks were shooting out of the amp, and when it got bad enough, I’d have to stop and lay bags filled with ice over the amp to cool it down

“Honestly, it was dangerous, but I couldn’t afford a new one. I was on my last legs, so I said, ‘Fuck it, let’s roll with this.’ It was so bad that sparks were shooting out of the amp, and when it got bad enough, I’d have to stop and lay bags filled with ice over the amp to cool it down.

“Once it cooled down, I’d have to rush to finish the take, and then it would start squealing again immediately. There were a few moments where I thought I pushed it past the point of no return. I’m shocked we didn’t burn the place down.”

You’ve said that if Everclear didn’t hit, that would be the end of your music career, and you’re still here. To what do you owe your longevity?

“Tenacity. Flat-out tenacity. I’m not good at anything else because there never was anything else for me. If Everclear failed, I probably woulda been an A&R guy or maybe gone into production. But it did work out, thankfully. I’m not a great instrumentalist. I’m not a great singer. But I can sit down and write a song and come up with a melody that you’ll remember, right?

You can’t teach how to make your voice match what you have on paper or hear in your head. No one can teach that. Either you have it, or you don’t

“I’m still here because I maximize that, keep working to stay creative and keep trying to learn. And when I teach people about songwriting, I’m like, ‘I can teach you how to structure a song. I can teach you what generally works and doesn’t work, but I can’t teach you melody.’

“You can’t teach how to make your voice match what you have on paper or hear in your head. No-one can teach that. Either you have it, or you don’t. I think I’m blessed to have that. At least, I think I do, and I guess that’s why I’m still hanging around.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

"I never use my tube amp at home now, because I have a Spark Live": 5 reasons you should be picking up the Positive Grid Spark Live in the massive Guitar Month sale

“Our goal is to stay at the forefront of amplification innovation”: How Seymour Duncan set out to create the ultimate bass amp solution by pushing its PowerStage lineup to greater heights