Archive: Jimmy Page Discusses Led Zeppelin's BBC Sessions

Here's one from the Guitar World archives: Brad Tolinski's exclusive interview with Jimmy Page regarding the 1997 release of Led Zeppelin: The BBC Sessions.

It's been a long time. Been a long, lonely time. Twenty-one years, to be precise, since Led Zeppelin officially released a live album, and 17 years since the band called it quits, due to the untimely death of drummer John Bonham.

So it came as something of a surprise, even a shock, when the Led Zeppelin: BBC Sessions dropped from the skies last month, a double-CD live set, consisting of music recorded for British radio in 1969 and 1971.

Disc one of Led Zeppelin: The BBC Sessions consists of 12 tracks drawn from several live BBC radio performances recorded in 1969, all presented in mono. Featured are rip-snorting renditions of early Zep classics like "You Shook Me" and "Whole Lotta Love," as well as a pair of songs previously unreleased by the band in any form: "The Girl I Love" (written by bluesman Sleepy John Estes) and rockabilly great Eddie Cochran's "Something Else."

Disc two is comprised of 10 tracks performed by Zeppelin at a BBC concert held at London's Paris Cinema theater on April 1, 1971, and is presented in stereo. Highlights include one of the band's earliest performances of "Stairway to Heaven" and a haunting acoustic set featuring "Going to California" and "That's The Way."

"Historically, they're good because those sessions are exactly what they are: a snapshot of a band trying to make their way through a very busy schedule," says Page, taking a short break from marathon recording sessions for an up-coming studio album with old pal Robert Plant.

Led Zeppelin: The BBC Sessions captures one of rock's very best bands at a pivotal moment in their career. The '69 and '71 radio performances document Zep's transition from testosterone-fueled steamroller to highly- evolved improvisational unit capable of building a celestial "Stairway to Heaven" one moment, only to knock it down with a wrecking-ball rendition of "Immigrant Song" the next.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"It's not the best Led Zeppelin, and it's not the worst," concludes Page, in this exclusive Guitar World interview. "It's what it was that night. Which in most cases, was very good."

GUITAR WORLD: When you dusted off the BBC sessions, what did you find most surprising about them?

JIMMY PAGE: I've heard the sessions several times throughout the years, so they weren't completely fresh to my ears. But what I find the most exciting about them is comparing the different versions of the same songs. It's interesting to hear how a song like "Communication Breakdown," which appears three times, evolved from performance to performance. It's like looking at a diary.

The BBC sessions show in graphic detail just how organic the group was. Led Zeppelin was a band that would change things around substantially each time it played. The two performances of "You Shook Me" are particularly good examples of what I'm talking about. The version that opens up the album is not shabby by any standards, but it doesn't compare to the second version, which was recorded only a few months later. The interplay between me and Robert had grown in leaps and bounds-he's laying right on top of the guitar. That kind of thing was a subtle indication of how the band was really beginning to gel. We were becoming tighter and tighter, to the point of telepathy.

I mean, compare our sessions to, say, the BBC recordings of the Beatles. I bet you a cent to a dollar, if they have two or three versions of "Love Me Do" or whatever, they'll all be identical. That's the difference between us and our contemporaries: Led Zeppelin were really moving the music all the time.

You mentioned that you had to edit some of the performances. Give us an example of the type of work you had to do.

I didn't have to do much. The biggest problem was editing down the 96 minute Paris Theater performance to the length of one CD, which is 80 minutes. Most of the editing was done on one song in particular-the "Whole Lotta Love" medley, which originally ran over 20 minutes. It included the band playing bits of "Let That Boy Boogie Woogie," "Fixin' to Die," "That's Alright Mama" and "Mess O' Blues," all of which were left in; and "Honey Bee," "The Lemon Song" and "For What It's Worth," which were edited out.

It was actually amazing the kind of editing we were able to with ProTools software-I was able to move things around quite a bit on the medley without disturbing the groove. For example, half of one of my solos is edited into the second half of another solo-and you'd never know! It's the kind of thing I just love doing. I really enjoy being given a problem that looks insurmountable, and finding a creative solution.

Are there any obvious gaffs that you left in?

There's a moment in the second version of "You Shook Me" that's funny and intense. The guitar comes in really loud, and you can tell that the engineer was caught by surprise because he panics and wacks the fader down. We left it because it's a very real moment. So, just in case anybody thinks it's my fault, don't blame me, I wasn't the engineer! [laughs]

But it's important to understand, that at the time, that kind of mistake wasn't a big deal. We never dreamed that there would be these things called CDs or that people would still be interested in any of the sessions 25 years later. It was purely for broadcast, and perhaps a repeat.

I noticed that some of the tracks have simple overdubs-maybe an added rhythm guitar behind your solos, or an extra harmony on one of the versions of "Communication Breakdown." Were these things you insisted on, or were they common practice?

I think at that time the BBC just wanted the best show possible. They realized that bands were often trying to recreate something that they had created on an eight-track recording, so doing an overdub here or there was fair game. At least one overdub, anyway, which is all we ever did.

What kind of shape were the original BBC tapes in?

That's a story in itself. When we first started entertaining the idea of releasing the sessions, we asked the BBC to send over copies of what they had. They sent Jon Astley, who assisted me in the remastering process, a DAT copy of the recording. Because they didn't send us the original quarter-inch masters, we just assumed they must have transferred everything to digital, and wiped the original tape. The plan was that we were going to remaster and edit from the DAT.

The interesting thing was, when I asked the BBC to send over the copies, I specifically requested a cassette tape, which I thought would be duped from the DAT. However, when we sat down to start remastering and Jon played me the digital tape and I thought, "My god, this sounds terrible. My mind might be playing tricks, but I think my cassette actually sounds much better than the DAT copy."

So I pulled out my cassette and, sure enough, my tape sounded much better. I then concluded that the cassette must have been duped from a different source-perhaps the original quarter-inch tape. So, following my hunch, we actually found the master tapes in their vaults. It took some searching, but it was worth the effort.

It's no secret that the Led Zeppelin BBC sessions are among the most bootlegged performances in rock history. They're kind of a hard rock version of Bob Dylan's Basement Tapes. To put it another way: if you're a serious Zeppelin fan, you've either heard or own some version of them. What's your view of bootlegging?

It depends. If it's someone with a microphone at a gig, that's one thing. They paid for a ticket, so it's fair game. But things that are stolen out of the studio-works in progress, rehearsal tapes and things like that-are quite another. I'm totally against that. It's theft. It's like someone stealing your personal journal and printing it.

Regarding the BBC sessions, it doesn't bother me if they've been bootlegged extensively because, whatever version people own, it won't be from the original source like our version. Secondly, not everybody out there buys bootlegs, and the sort of fans that buy bootlegs will want this one for the packaging-and to see how I've edited the performances. I can't really lose. There's no way I'll lose! [laughs]

One of the more striking differences between the two BBC Session CDs, is that by 1971, you had pretty much stopped covering traditional blues songs.

Well, we started writing our own blues songs, didn't we? After the first album, I was really conscious of the fact that we had to start carving our own identity. I felt a particular pressure to make my unique personal contribution.

In the early days, I was quite happy to borrow from Otis Rush for "I Can't Quit You." It was a pleasure. But after a while I started realizing that that wasn't what I should be doing. I felt I had to start developing my own thing and almost stop listening to anybody. And I think I succeeded.

"Whole Lotta Love" is a good example. We got into some trouble because people felt we lifted it from Willie Dixon, but if you took the lyric out and listened to the track instrumentally, it is clearly something new and different-a completely original piece of music.

Another good example is "Nobody's Fault But Mine," from Presence. Robert came in one day and suggested we cover it, but the arrangement I came up with has nothing to do with the [Blind Willie Johnson] original. Robert may have wanted to go for the original blues lyrics, but everything else was a totally different kettle of fish. Actually, I only recently discovered that "The Girl I Love," had something to do with Sleepy John Estes! [laughs]

What was your original concept for Zeppelin?

Ultimately, I wanted Zeppelin to be a marriage of blues, hard rock and acoustic music topped with heavy choruses-a combination that had never been done before. Lots of light and shade.

I was looking at some old photos of the band recently, and I noticed you had a real assortment of fairly bizarre amplifiers and guitars in '69. What were you using before you switched to the Marshall Super Lead/Les Paul combination that most people associate with you?

It was basically whatever we could afford at that time. I didn't really make any money when I was with the Yardbirds, so I was pretty broke in the beginning. I actually had to finance the first Zeppelin album with money I had saved as a session musician. What I had as equipment was very minimal. I had my Telecaster that Jeff Beck gave me, a Harmony acoustic, a bunch of Rickenbacker TransSonic cabinets left over from the Yardbirds, and a hodge-podge of amps-Vox and Hiwatts, mostly.

I also had a black Les Paul Custom with a big tremolo arm that was stolen during the first 18 months of Zeppelin. It was lifted at the airport. We were on our way to Canada, and, somewhere, there was a flight change and it disappeared. It never arrived at the other end. All I used for pedals was an Echoplex, a Tonebender distortion and a wah-wah.

What are you playing on the '69 sessions?

The Telecaster. I'm not really sure about the amp.

Did you switch to the Les Paul because you felt that at some level the Tele wasn't cutting it?

No. If you listen to the first album, the Tele is doing all of that with the pedals I just mentioned. It was certainly doing the job.

So why did you leave it behind?

When Joe Walsh was trying to sell me his Les Paul, I said, "I'm quite happy with my Telecaster." But as soon as I played it I fell in love. Not that the Tele isn't user friendly, but the Les Paul was so gorgeous and easy to play. It just seemed like a good touring guitar.

How did the four members of Zeppelin interact on a personal level? Was everything as smooth internally as it appeared to be?

I think the atmosphere in Led Zeppelin was always an encouraging one. We all wanted to see the music get better. And part of the reason things ran smoothly is that I had the last decision on everything. I was the producer, so there weren't going to be any fights.

The atmosphere was always very professional. I was meticulous with my studio notes, and everybody knew that they would get proper credit, so everything was fine.

Another key: we all lived in different parts of the country, so when we came off the road we didn't really see each other. I think that helped. We really only socialized when we were on the road. We all really came to value our family lives, especially after being on the road so much, which is how it should be. It helped create a balance in our lives. Our families helped keep us sane.

Stay tuned for part 2 of this classic interview

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away Brad was the editor of Guitar World from 1990 to 2015. Since his departure he has authored Eruption: Conversations with Eddie Van Halen, Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page and Play it Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, which was the inspiration for the Play It Loud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2019.

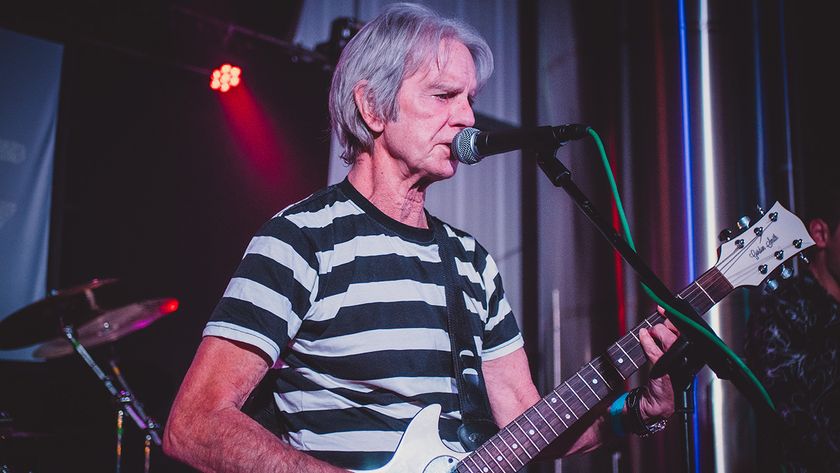

“I get asked, ‘What’s it like being a one-hit wonder?’ I say, ‘It’s better than being a no-hit wonder!’” The Vapors’ hit Turning Japanese was born at 4AM, but came to life when two guitarists were stuck into the same booth

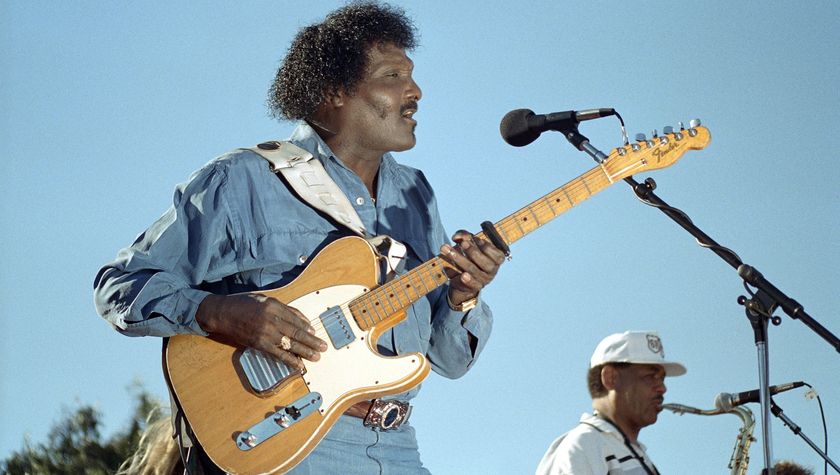

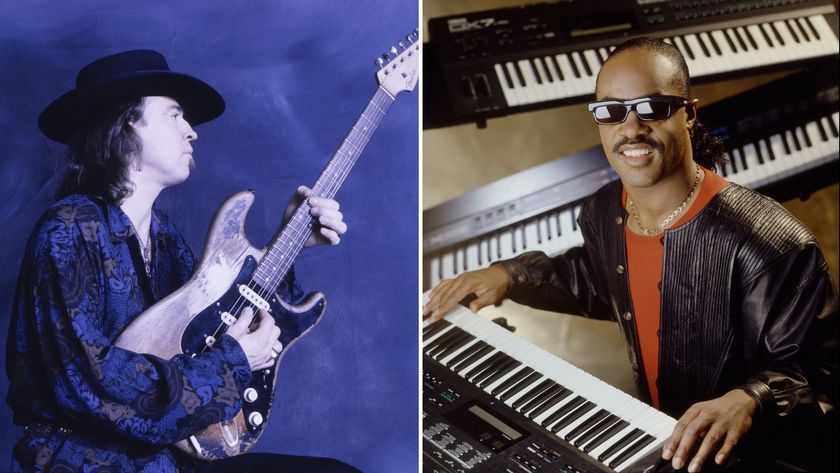

“Let's play... you start it off now, Stevie”: That time Stevie Wonder jammed with Stevie Ray Vaughan... and played SRV's number one Strat

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)